Arthur Evans

Arthur John Evans (born July 8, 1851 – died July 11, 1941) was a British archaeologist, best remembered for uncovering, at the island of Crete, previously unknown Minoan civilization.

Life

Arthur John Evans was born in Nash Mills, England. He was the eldest son of Sir John Evans, a paper manufacturer and amateur archaeologist of Welsh descent, who evoked in his son a great interest for archeology. Evans was educated at Harrow School, at Brasenose College, Oxford, and at the University of Göttingen, where he obtained a degree in history.

In 1878, he married Margaret Freeman, who became his companion and a partner in his work, until her death in 1893.

After graduation, Evans traveled to Bosnia and Macedonia to study ancient Roman sites. At the same time, he was working as a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian in the Balkans and a secretary of the British Fund for Balkan Refugees. However, due to his critical position toward local government he made himself lot of enemies. In 1882, he was accused of being a spy, arrested, and expelled out of the country.

In 1884, he became curator of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the position he carried until 1908, when he was made professor of prehistoric archaeology. In 1901, he became a fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1911 he received a knighthood. He served as president of the Society of Antiquities from 1914 to 1919, and president of the British Association from 1916 to 1919.

Evans, however remains most famous for his archeological excavations on the island of Crete. He visited Crete for the first time in 1894, when an unknown script, made out on seal stones, was found together with some unidentified coins. After he studied the sites on Crete, he proposed the explanation that the pre-classical Mycenaean civilization of Greece originated in Crete. He published his ideas in the Cretan Pictographs and Pre-Phoenician Script in 1895.

Four years later, for the sole purpose of excavations, he purchased the site of Knossos, which became a treasure trove of various finds. There, Evans uncovered the ruins of a palace, the restoration of which he worked on for the rest of his life. Following the Greek legend of the Cretan king Minos and a beast called Minotaur, Evans coined the name "Minoan" and gave it to this newly found civilization.

By 1903, most of the palace was excavated, revealing the beauty of Minoan artwork, through the hundreds of artifacts and writings that he found. Evans described his work on excavations in his 4 volume The Palace of Minos at Knossos which he published from 1921 to 1935.

Evans continued his excavations until he was 84 years old. He died in a small town of Youlbury near Oxford in 1941.

Work

Evans' interest for the island of Crete, which according to the Greek legends hosted an ancient civilization of "Minoans," was sparked by Heinrich Schliemann’s discovery of legendary Troy. As was Schliemann, Evans was an amateur archaeologist, driven by his passion for mythology of the ancient world. He believed that King Minos, described in some of the Greek stories, was real, and that Crete was the home of a once great civilization. This conviction led him to invest all his inheritance, purchasing a great piece of land, including the ruins of the palace of Knossos, which he spent his life excavating.

Evans, however, should also be remembered for his own irrationally obstinate Creto-centrism, which led to unfriendly debate between himself and the mainland archaeologists Carl Blegen and Alan Wace. He disputed Blegen's speculation that the writings he found at Pylos of Linear B were actually a form of archaic Greek. Evans' insistence upon a single timeline for Bronze Age Greek civilization, based upon his dating of Knossos and other Minoan palaces, ran contrary to Wace's dating of Mycenae, which saw its heyday in the midst of Knossos' decline. Evans generated strange and convoluted explanations for these findings, and in enmity, he actually used his influence to have Wace removed from his tenured position at the British School of Archaeology in Athens.

Knossoss

After unearthing the remains of the city and its palace, including the structure of a labyrinth, Evans was convinced that he had finally found the Kingdom of Minos and its legendary half-bull half-man Minotaur.

He published an account of his findings in four volumes The Palace of Minos at Knossos (1921–1935), a classic of archaeology. However, he also substantially restored and partially reconstructed these remains, using foreign materials such as concrete that are offensive to purists.

While many of his contemporaries were interested in removing items of interest from the sites they uncovered, Evans wanted to turn Knossos into a museum where Minoan civilization could become tangible, as he was far more interested in building a whole vision of the past than simply displaying its riches. Thus, his reconstructions help the average visitor "read" the site, allowing them to appreciate and enjoy the beauty of the culture he had uncovered.

Linear A and Linear B

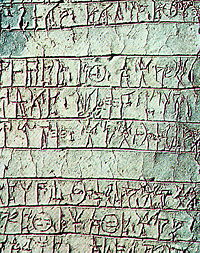

Also on Crete, Evans discovered writings in an unknown script. Though deciphering and translating the scripts found on the site always eluded him, Evans recognized that they were in two scripts, which he dubbed Linear A and Linear B. He – correctly, as it turned out – suggested that Linear B was written in a language that used inflection.

Linear B was deciphered in the 1950s by Michael Ventris as representing an ancient form of Greek. Linear A remains an undeciphered script. Its decipherment is one of the "Holy Grails" of ancient scripts.

Legacy

Arthur Evans is one of the most well-known archaeologists in history. He was knighted in 1911 for his services to archaeology, and is commemorated both at Knossos and at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford University. The timeline of Minoan civilization, which he constructed, although slightly revised and updated, is still considered rather accurate. The excavation at the site of Knossos has been continued to the present day by the British School of Archaeology in Athens.

Evans used contemporary material to reconstruct the old ruins of Knossos, according to the way he thought the original structures would have looked. This drew serious criticism from contemporary scholars, but Evans seemingly didn’t pay much attention to it. He rebuilt what looked like to be a labyrinth, and build numerous new structures on the old ones, following his own vision of Minoan architecture. In this way, he blended old and new constructions, only a trained eye being able to see the difference. This practice is strongly condemned by modern archaeologists.

Publications

- Evans, Arthur J. 1883. Review of Schliemann’s Troja. Academy, 24, 437-39.

- Evans, Arthur J. 1889. Stonehenge. Archaeological Review, 2, 312-30.

- Evans, Arthur J. 1896. Pillar and Tree-Worship in Mycenaean Greece. Proceedings of the British Association (Liverpool), 934.

- Evans, Arthur J. 1905. Prehistoric Tombs of Knossos. Archaeologia, 59, 391-562.

- Evans, Arthur J. 1915. Cretan Analogies for the Origin Alphabet. Proceedings of the British Association (Manchester), 667.

- Evans, Arthur J. 1919. The Palace of Minos and the Prehistoric Civilization of Crete. Proceedings of the British Association (Bournenouth), 416-17.

- Evans, Arthur J. 1925. The ‘Ring of Nestor’: a Glimpse Into the Minoan After-World. Journal of Hellenic Studies, 45, 1-75.

- Evans, Arthur J. 1929. The Shaft-Graves and Bee-Hive Tombs of Mycenae and Their Inter-relations, London, Macmillan

- Evans, Arthur J. 1921-1935. The Palace of Minos at Knossos (4 Vols.). London: Macmillan

- Evans, Arthur J. 1938. An Illustrative Selections of Greek and Greco-Roman Gems. Oxford University Press.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Ann C. 1993. Before Knossos: Arthur Evans Travels in the Balkans and Crete. Ashmolean Museum. ISBN 1854440306

- Horowitz, Sylvia L. 2001. Phoenix: The Find of a Lifetime: Sir Arthur Evans and the Discovery of Knossos. Phoenix Press. ISBN 1842122215

- Macgillivray, J. A. 2000. Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. Hill & Wang, ISBN 0809030357

External Links

- Sir Arthur Evans and the Excavation of the Palace at Knossos – Article from Athena Review in 2003

- Bio-bibliography – Short biography with bibliography

- Biography - Short biography

- Palace at Knossos - Website with photos of the palace of Knossos

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.