Shiloh (Bible)

Shiloh (Hebrew: ◊©◊ú◊Ē - ҆ńęlŇćh) was a city in ancient Israel, situated north of Bethel and south of Shechem in the hill-country of Ephraim (Judg. 21:19). During the period of judges, it was a major religious center and the permanent cite of the sacred Tabernacle, which the Israelites had carried through the wilderness.

The Bible describes Shiloh as an assembly place for the people of Israel from the time of Joshua. Sacrifices were brought there by the Israelites during the period of judges, and it was also the site of various religious celebrations and festivals. The prophet Samuel was reportedly raised there, and the Ark of the Covenant remained at Shiloh until it was captured by the Philistines in the battle of Aphek during the time of the high priest Eli.

Shiloh declined in importance after this, and especially after the establishment of the Temple of Jerusalem. However, it became briefly famous as the home of the prophet Ahijah of Shiloh, who commissioned Jeroboam I to become the king of Israel in opposition to the Davidic dynasty.

Some biblical scholars believe that the Shilonite priesthood was the origin of the Elohist source according to the documentary hypothesis of biblical criticism. In Samaritan tradition, Shiloh was an illegitimate rival shrine to the ancient Samaritan holy place of Mount Gerizim.

A modern Israeli settlement has been established adjacent to Tel Shiloh next to the Palestinian town Turmus Ayya. About 1200 people live in Shiloh proper, with about another 700 people living within its municipal boundaries. The future of modern Shiloh-whether it will become part of a future Palestinian state or be claimed as Israeli territory-is disputed.

Biblical Shiloh

At Shiloh, the "whole congregation of Israel assembled…and set up the tabernacle of the congregation" (Joshua 18:1). According to Talmudic sources, the Tabernacle rested at Shiloh for 369 years (Zevachim 118b), although modern scholars believe the period to have been considerably shorter.

At some point during its stay at Shiloh, the portable tent seems to have been enclosed within a compound or replaced with a standing structure with permanent doors (1 Samuel 3:15), a precursor to the Temple. Though other important places of worship and government existed during this period, Shiloh was a major religious center. "The people," assembled here for feasts and sacrifices, and here the lots were cast under Joshua's guidance for the various tribal areas (Joshua 18:10) and Levitical cities (Joshua 21).

The centrality of Shiloh's altar became a bone of contention when the eastern tribes‚ÄĒReuben, Gad, and Manasseh‚ÄĒbuilt their own worship center near the Jordan River, nearly provoking an inter-tribal war until these tribes agreed that the altar would serve only as a monument and not a rival place of sacrifice (Joshua 22:28). Nevertheless, other sacrificial altars were clearly in evidence during the period, including at Mount Ebal (Joshua 8:30), Ophrah (Judges 6:24), Zorah (Judges 13:20) (Joshua 24:26), Bethel (Judges 21:4), Ramah (1 Samuel 7:17), Gilgal (1 Samuel 10:8), and others.

When a war between the tribe of Benjamin and other Israelite tribes left the Benjaminites without an adequate number of women, Shiloh's role as a religious center presented a bizarre solution. As part of the peace settlement, the leaders of the other tribes gave the Benjaminites permission to kidnap wives for themselves during a religious celebration as the young women came from Shiloh's shrine to dance in the nearby vineyards (Judges 21).

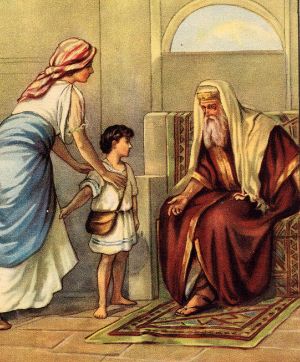

Later, the prophet Samuel was raised at the shrine in Shiloh by the high priest Eli. Meanwhile, Eli's sons Hophni and Phinehas had become corrupt, and another prophet predicted that God's blessing would be removed from Eli's lineage. When the Philistines confronted the Israelites at Aphek, the Israelites brought forth the Ark of the Covenant from Shiloh as their standard. Although this act temporarily threw the Philistines into confusion, they were able to rally effectively, defeat the Israelites, and carry the Ark off to Philistia. The Ark was soon returned to Israel, but was subsequently kept in Kiryat-Yearim until David had it brought to Jerusalem. It never returned to Shiloh. Some believe that Shiloh itself may have been destroyed by the Philistines at this time, although this is not indicated in the record.

During the reign of King Saul, Eli's descendants Ahimelech and Abiathar were to be found at an otherwise unknown religious center called Nob, where they gave aid to the fugitive David and were infamously attacked by agents of Saul, with only the young Abiathar surviving the slaughter. Some of the Shilonite priests came to Jerusalem during the reign of King David, who brought the Ark of the Covenant to his new capital and established a central altar there. Abiathar, who was Eli's great-grandson, served as David's high priest together with Zadok until he made the mistake of backing Adonijah instead of Solomon as David's successor, for which he was banished by Solomon.

Other than Eli and Samuel, the most famous Shilonite was the prophet Ahijah. After Solomon had sinned by constructing altars to honor the gods of his Moabite and Ammonite wives near Jerusalem, Ahijah commissioned Jeroboam I as the future king of Israel, leaving only the territory of Judah to David's descendants. When Solomon died, ten of the tribes seceded and made Jeroboam their king. Local worship sites were revived as alternative pilgrimage destinations to Jerusalem's temple. At this time, Shiloh may have been revived as a holy shrine. In any case it was home to Ahijah, who later turned against Jeroboam for creating the shrines at Dan and Bethel. While living out his days at Shiloh, Ahijah predicted the demise of Jeroboam's line (1 Kings 14:6-16).

Shiloh virtually disappears from the biblical record after this. However, in the early sixth century B.C.E., the prophet Jeremiah would refer to Shiloh's shrine as a place of desolation, predicting that God would do likewise to Jerusalem if its priests and people did not repent:

Do not trust in deceptive words and say, "This is the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord!" … Go now to the place in Shiloh where I first made a dwelling for my Name, and see what I did to it because of the wickedness of my people Israel … What I did to Shiloh I will now do to the house that bears my Name, the temple you trust in, the place I gave to you and your fathers (Jeremiah 7:4-14).

Nevertheless, Jeremiah also indicates that Shiloh remained prosperous enough that a few years later‚ÄĒalong with the important northern cities of Shechem and Samaria‚ÄĒit could send delegates with expensive grain and incense offerings to the Jewish governor, Gedaliah, during the early period of Babylon rule (Jeremiah 41:5).

The Elohist and Shiloh

A number of biblical scholars who accept the documentary hypothesis of biblical criticism believe that the "Elohist" ("E") source of the Pentateuch originated from Shiloh. In this theory, Shiloh continued as a competing center of worship and literary activity in the early days of the Temple of Jerusalem, which the Shilonite priests treated as their opponent and rival.

According to this theory, the priests of Shiloh were not of the Aaronid or Levite priesthood. "E" thus denigrates the priesthood of Aaron through such stories as the Golden Calf and Aaron's criticism of Moses' wife. The E version of the Ten Commandments is also thought to condemn both the golden calves at the rival northern worship centers at Dan and Bethel, and the gold-plated cherubim of the Aaronid priesthood at the Temple of Jerusalem:

Do not make any gods to be alongside me; do not make for yourselves gods of silver or gods of gold. Make an altar of earth for me… If you make an altar of stones for me, do not build it with dressed stones, for you will defile it if you use a tool on it (Exodus 20:23-25).

Some scholars believe it was Shiloh that originally housed the Nehustan, the bronze snake created by Moses in the wilderness, which was later moved to Jerusalem but was eventually destroyed by King Hezekiah as an object of idolatry (2 Kings 18:4). The "E" verses found in the Book of Numbers explain the origin of this sacred object:

And the Lord said unto Moses, "Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole: and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he looketh upon it, shall live." And Moses made a serpent of brass, and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, when he beheld the serpent of brass, he lived (Numbers 21:8-9).

Shiloh in Samaritan tradition

Shiloh also plays a role in Samaritan tradition, where it is portrayed as an illegitimate shrine created by Eli as a rival to the authorized altar of Yahweh at Mount Gerizim. The Samaritans assert that Mount Gerizim was the original site intended by God as the location of his Temple.

After being ousted from the true priesthood and establishing himself at Shiloh, Eli allegedly prevented southern pilgrims from Judah and Benjamin from attending the Gerizim shrine. He also fashioned a duplicate of the Ark of the Covenant, and it was this replica that eventually made its way to the Judahite Temple of Jerusalem. Eli's protégé, Samuel, later anointed David, a Judahite, as the first king of the supposedly united kingdom of Judah/Israel. However, Samaritan tradition recognizes neither the kings of Judah nor those of the northern kingdom of Israel as legitimate.

Later references

In the Common Era, Shiloh is occasionally mentioned as a pilgrimage site of Christians and Muslims. St. Jerome, in his letter to Paula and Eustochius, dated about 392-393, wrote: "With Christ at our side we shall pass through Shiloh and Bethel." However, the church of Jerusalem did not schedule an annual pilgrimage to Shiloh, unlike Bethel. The only pilgrim other than Jerome that mentions its name‚ÄĒthe sixth century pilgrim, Theodosius‚ÄĒwrongly located it mid-way between Jerusalem and Emmaus. This and other mistaken identifications lasted for centuries. Nevertheless, recent archaeological discoveries have revealed the existence of at least three ancient Byzantine churches at Tel Shiloh.

Muslim pilgrims to Shiloh mention a mosque called es-Sekineh where the memory of Jacob's and Joseph's deeds was revered. The earliest source is el-Harawi, who visited the country in 1173 when it was occupied by the Crusaders, wrote: "Seilun (Shiloh) is the village of the mosque es-Sekineh where the stone of the Table is found." Later Muslim writers make similar mentions of the site.

Shiloh assumed messianic attachment among Christians due to the verse (Genesis 49:10): "The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor a lawgiver from between his feet, until Shiloh comes, and unto him shall the gathering of the people be." Shiloh here is believed by some Christians to refer to Jesus as the Messiah.

Archaeology

The first archaeological excavations at Tel Shiloh began in the years 1922-1932, by a Danish expedition. The finds were placed in the Danish National Museum in Copenhagen. In 1980, Israel Finkelstein, an archaeologist from Bar-Ilan University, initiated four seasons of digs, revealing coins, storage jars, and other artifacts. Many of these are preserved at Bar-Ilan University. In 1981-1982, Zeev Yeivin and Rabbi Yoel Bin-Nun dug out from the bedrock area of the presumed site of the Tabernacle. Ceramics and ancient Egyptian figurines were found.

These and other excavations have shown that the site of Shiloh was already settled as early as the nineteenth century B.C.E. (Middle Bronze Age IIA). However, the site is not recognizably mentioned in any pre-biblical source. It has yielded impressive remains from the Caananite and Israelite eras until the eighth century B.C.E. Excavations have also revealed remains from the Roman and Persian, as well as early and late Islamic periods. A substantial earthworks has been located; and pottery, animal remains, weapons, and other objects have been recovered.

During the summer of 2006, archaeological excavations were carried out adjacent to Shiloh’s tel. A team led by Israel's Civilian Administration Antiquities Unit discovered the mosaic floor of a large Byzantine church which was probably constructed between 380 and 420 C.E. The following year, a dig carried out just south of Tel Shiloh exposed elaborate mosaic floors as well as several Greek inscriptions, one explicitly referring to the site as the "village of Shiloh." A total of three Byzantine basilicas have now been uncovered.

Modern Shiloh

Shiloh resumed its status as a Jewish town in 1978, when a group of Jews affiliated with the Gush Emunim settlement movement established themselves at the location to assert Jewish rights to the area. In 1979, the Israeli government officially authorized Shiloh's status as a recognized village. The population (2006) of the village is approximately 1500 and the community contains educational institutions, a grocery, a yeshiva, sports fields, a pool, and several synagogues, one scale-modeled to the ancient Tabernacle. The village is built on disputed territory, claimed by the Palestinian Authority as part of a potential independent state.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, Robert T., and Terry Giles. The Keepers: An Introduction to the History and Culture of the Samaritans. Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. ISBN 978-1565635197.

- Cross, Frank Moore. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic; Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1973. ISBN 978-0674091757.

- Evans, Mary. The Message of Samuel: Personalities, Potential, Politics, and Power. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004. ISBN 0830824294.

- Grant, Michael. The History of Ancient Israel. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1984. ISBN 0684180812.

- Keller, Werner. The Bible as History. Bantam, 1983. ISBN 0553279432.

- Miller, J. Maxwell. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0664223588.

External links

All links retrieved January 27, 2023.

- Shiloh in the Jewish Encyclopedia www.jewishencyclopedia.com

- Photos of Shiloh www.pbase.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.