Seleucus I Nicator

| Seleucus I Nicator | ||

|---|---|---|

| Founder of the Seleucid Empire | ||

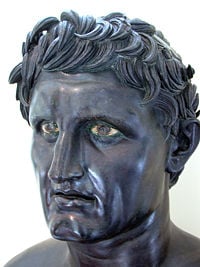

| Bust of Seleucus I | ||

| Reign | 305 B.C.E. - 281 B.C.E. | |

| Coronation | 305 B.C.E., Seleucia | |

| Born | 358 B.C.E. | |

| Orestis, Macedon | ||

| Died | 281 B.C.E. (aged 77) | |

| Lysimachia, Thrace | ||

| Predecessor | Alexander IV of Macedon | |

| Successor | Antiochus I Soter | |

| Father | Antiochus | |

| Mother | Laodice | |

Seleucus I (surnamed for later generations Nicator, Greek: Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ (Seleucus Victor) (ca. 358 B.C.E.–281 B.C.E.), was a Macedonian officer of Alexander the Great. In the Wars of the Diadochi that took place after Alexander's death, Seleucus established the Seleucid dynasty and the Seleucid Empire. His kingdom would be one of the last holdouts of Alexander's former empire to Roman rule. They were only outlived by the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt by roughly 34 years. A great builder of cities, several of Seleucus' foundation went on to make significant cultural and intellectual contributions to the sum of human knowledge. The town built to honor his own birth, Dura Europis is both an important archaeological center and a testimony to the multicultural vitality of Seleucid society.

On the one hand, conquered populations were expected to embrace aspects of Greek culture. On the other hand, the colonizers also embraced aspects of the culture of the colonized. Some Babylonian deities fused with their Greek counterparts while different religions were practiced in parallel in what for much of the time was a climate of mutual respect. Despite the excesses of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, its eighth ruler, the empire founded by Seleucus I Nicator, alongside others that have helped to build cultural bridges, played a pivotal role in the maturation of humanity towards willingness to embrace what has value in any culture, to view all knowledge as the patrimony of the everyone, and to regard the welfare of all as a shared responsibility.

Early career and rise to power

Seleucus was the son of Antiochus from Orestis,[1] one of Philip's generals, and of Laodice. In spring 334 B.C.E., as a young man of about 23, he accompanied Alexander into Asia. By the time of the Indian campaigns beginning late in 327 B.C.E. he had risen to the command of the élite infantry corps in the Macedonian army, the "Shield-bearers" (Hypaspistai), later known as the "Silver Shields." He also took his future wife, the Persian princess Apama, with him into India as his mistress, where she gave birth to his bastard eldest son Antiochus (325 B.C.E.), the later Antiochus. At the great marriages ceremony at Susa in spring 324 B.C.E. Seleucus formally married Apama, and she later bore him at least two legitimate daughters, Laodike and Apama. After Alexander's death when the other senior Macedonian officers unloaded the "Susa wives" en masse, Seleucus was one of the very few who kept his, and Apama remained his consort and later Queen for the rest of her life.

When the enormous Macedonian dominion was reorganized in summer 323 B.C.E. (the "Partition of Babylon"), Seleucus was appointed first or court chiliarch, which made him the senior officer in the Royal Army after the Regent and commander-in-chief Perdiccas. Subsequently, Seleucus had a hand in the murder of Perdiccas during the latter's unsuccessful invasion of Egypt in 320 B.C.E.

At the second partition, at Triparadisus (321 B.C.E.), Seleucus was given the government of the Babylonian satrapy. In 316 B.C.E., when Antigonus had made himself master of the eastern provinces, Seleucus felt himself threatened and fled to Egypt. In the war which followed between Antigonus and the other Macedonian chiefs, Seleucus actively cooperated with Ptolemy and commanded Egyptian squadrons in the Aegean Sea.

The victory won by Ptolemy at the battle of Gaza in 312 B.C.E. opened the way for Seleucus to return to the east. His return to Babylon was afterwards officially regarded as the beginning of the Seleucid Empire and that year as the first of the Seleucid era. Master of Babylonia, Seleucus at once proceeded to wrest the neighboring provinces of Persia, Susiana and Media from the nominees of Antigonus. Raids into Babylonia conducted in 311 B.C.E. by Demetrius, son of Antigonus, and by Antigonus himself in 311/310 (the Babylonian War), did not seriously check Seleucus' progress. Over the course of nine years (311-302 B.C.E.), while Antigonus was occupied in the west, Seleucus brought the whole eastern part of Alexander's empire as far as the Jaxartes and Indus Rivers under his authority.

In 305 B.C.E., after the extinction of the old royal line of Macedonia, Seleucus, like the other four principal Macedonian chiefs, assumed the title and style of basileus (king). He established Seleucia on the Tigris as his capital.

Establishing the Seleucid state

India

In the year 305 B.C.E. Seleucus I Nicator went to India and apparently occupied territory as far as the Indus, and eventually waged war with the Maurya Emperor Chandragupta Maurya:

Always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he [Seleucus] acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus. He crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus, king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship.[2]

As most historians note, Seleucus appears to have fared poorly as he did not achieve his aims. The two leaders ultimately reached an agreement, and through a treaty sealed in 305 B.C.E., Seleucus ceded a considerable amount of territory to Chandragupta in exchange for 500 war elephants, which were to play a key role in the battles that were to come. According to Strabo, these were territories bordering the Indus:

The Indians occupy [in part] some of the countries situated along the Indus, which formerly belonged to the Persians: Alexander deprived the Ariani of them, and established there settlements of his own. But Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus in consequence of a marriage contract, and received in return five hundred elephants.[3][4]

Modern scholarship often considers that Seleucus actually gave more territory, in what is now southern Afghanistan, and parts of Persia west of the Indus. This would tend to be corroborated archaeologically, as concrete indications of Mauryan influence, such as the inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka, are known as far as Kandhahar, in today's southern Afghanistan.

Some authors claim this is an exaggeration, which comes from a statement made by Pliny the Elder, referring not specifically to the lands received by Chandragupta, but rather to the various opinions of geographers regarding the definition of the word "India":[5]

The greater part of the geographers, in fact, do not look upon India as bounded by the river Indus, but add to it the four satrapies of the Gedrose, the Arachotë, the Aria, and the Paropamisadë, the River Cophes thus forming the extreme boundary of India. All these territories, however, according to other writers, are reckoned as belonging to the country of the Aria.[6]

Also the passage of Arrian explaining that Megasthenes lived in Arachosia with the satrap Sibyrtius, from where he visited India to visit Chandragupta, goes against the notion that Arachosia was under Maurya rule:

Megasthenes lived with Sibyrtius, satrap of Arachosia, and often speaks of his visiting Sandracottus, the king of the Indians. — Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri.[7]

Nevertheless, it is usually considered today that Arachosia and the other three regions did become dominions of the Mauryan Empire.

To cement the treaty, there was either some sort of marriage alliance (Epigamia) involving Seleucus' daughter or the diplomatic recognition of intermarriage between Indians and Greeks. Helweg reports on "suggestions that Asoka's father married a daughter of Seleucus."[8]

In addition to this matrimonial recognition or alliance, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to the Mauryan court at Pataliputra (Modern Patna in Bihar state). The two rulers seem to have been on very good terms, as Classical sources have recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta sent various presents such as aphrodisiacs to Seleucus.[9]

Seleucus obtained knowledge of most of northern India, as explained by Pliny the Elder through his numerous embassies to the Mauryan Empire:

The other parts of the country [beyond the Hydaspes, the farthest extent of Alexander's conquests] were discovered and surveyed by Seleucus Nicator: namely

- from thence (the Hydaspes) to the Hesudrus 168 miles

- to the river Ioames as much: and some copies add 5 miles more thereto

- from thence to Ganges 112 miles

- to Rhodapha 119, and some say, that between them two it is no less than 325 miles.

- From it to Calinipaxa, a great town 167 miles-and-a-half, others say 265.

- And to the confluent of the rivers Iomanes and Ganges, where both meet together, 225 miles, and many put thereto 13 miles more

- from thence to the town Palibotta 425 miles

- and so to the mouth of Ganges where he falleth into the sea 638 miles."[10]

Seleucus apparently minted coins during his stay in India, as several coins in his name are in the Indian standard and have been excavated in India. These coins describe him as "Basileus" ("King"), which implies a date later than 306 B.C.E. Some of them also mention Seleucus in association with his son Antiochus as king, which would also imply a date as late as 293 B.C.E. No Seleucid coins were struck in India thereafter and confirm the reversal of territory west of the Indus to Chandragupta.[11]

Asia Minor

In 301 B.C.E. he joined Lysimachus in Asia Minor, and at Ipsus Antigonus fell before their combined power. A new partition of the empire followed, by which Seleucus added to his kingdom Syria, and perhaps some regions of Asia Minor.

In 300 B.C.E., after the death of Apama, Seleucus married Stratonice, daughter of Demetrius Poliorcetes. Seleucus had a daughter by Stratonice, who was called Phila. In 294 B.C.E. Stratonice married her stepson Antiochus. Seleucus reportedly instigated the marriage after discovering that his son was in danger of dying of lovesickness.[12]

The possession of Syria gave him an opening to the Mediterranean, and he immediately founded the new city of Antioch on the Orontes as his chief seat of government. Seleucia on the Tigris continued to be the capital for the eastern satrapies. About 293 B.C.E., he installed his son Antiochus there as viceroy, the vast extent of the empire seeming to require a double government.

The capture of Demetrius in 285 B.C.E. added to Seleucus's prestige. The unpopularity of Lysimachus after the murder of Agathocles gave Seleucus an opportunity for removing his last rival. His intervention in the west was solicited by Ptolemy Keraunos, who, on the accession to the Egyptian throne of his brother Ptolemy II (285 B.C.E.), had at first taken refuge with Lysimachus and then with Seleucus. War between Seleucus and Lysimachus broke out, and at the decisive battle of Corupedium in Lydia, Lysimachus fell (281 B.C.E.). Seleucus now held the whole of Alexander's conquests except Egypt in his hands, and moved to take possession of Macedonia and Thrace. He intended to leave Asia to Antiochus and content himself for the remainder of his days with the Macedonian kingdom in its old limits. He had, however, hardly crossed into the Chersonese when he was assassinated by Ptolemy Keraunos near Lysimachia (281 B.C.E.).

Founder of Cities

It is said of Seleucus that "few princes have ever lived with so great a passion for the building of cities. ... He is said to have built in all nine Seleucias, sixteen Antiochs, and six Laodiceas."[13] One of the cities founded by Seleucus I was Dura-Europeas, built to mark his own birth-place. This is an important archeological site; Roman, Greek, Iranian temples as well as a synagogue and a church all testify to a thriving multicultural society.

Administration, Society and Religion

Seleucus claimed descent from Apollo.[14] There is evidence that he was also worshiped as Zeus.[15] After his death, he was worshiped as "divine," as were subsequent rulers of the dynasty. Later, Antiochus I "reconstructed the main temple" dedicated to the Babylonian deities Nabu (wisdom, writing) and Nanaia (his consort) in Borsippa."[16] The goddess was often identified with Artemis. Edwards comments that the Seleucids were much more respectful of the local temples, deities and customs than "was previously thought."[17]

Due to the size of the empire, it was administratively sub-divided into several vice-royalties.[18] The heads of these "special commands" were usually members of the imperial family. The army employed both Greeks and non-Greeks; the later were drawn from "regions whose social structures involved and encouraged strong warlike traditions."[19] Seleucid I adopted the use of elephants from India and had over a hundred in his cavalry.

Marriage across ethnic groups was not uncommon, especially in the cities. Seleucus almost certainly shared Alexander's view of racial unity and encouraged inter-marriage as a stepping stone to achieving one world, one nation, one cultural melting pot.[20] Edwards et al. argue that the Seleucid empire was of a distinctly "Oriental" type; the monarch was "lord of the land" while the population were dependent on but not enslaved" to the king.[21]

Legacy

As did the Ptolemies in Egypt, the dynasty that took its name from Seleucus I adapted aspects of the surrounding culture. More than the Ptolemies did in Egypt, though, they also championed Hellenistic culture and philosophy and sometimes committed excesses, alienating the local population. This was especially true under Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who provoked the Maccabean revolt in part of the empire. On the other hand, they also championed cultural fusion. For example, they used the Babylonian calendar, and took part in Babylonian religious festivals especially in the Akitu Festival, the New Year.[22] As the Ptolemies adopted the Egyptian ideology of kingship, the Seleucids borrowed from Persian concepts. The Persians, like the Egyptians, saw the King as "divine." There is some evidence that a cult developed around the Seleucid rulers. The Seleucids "showed piety towards indigenous Gods."[23] Cultural exchange was a two-way process; the conquered populations were expected to embrace aspects of Greek culture but the colonizers also embraced aspects of the culture of the colonized.

Generally, the Seleucids presided over a cultural melting plot, inheriting Alexander's ideas about racial unity. Antioch, founded by Seleucus I, became an important center of primitive Christianity, the seat of an ancient bishopric. The city was built to resemble Alexandria. It became the empire's capital under Antiochus I Soter. It was in the former Seleucid empire that Muslims first encountered Greek learning and, in the Islamic academies of the eighth and ninth century. Greek classics were translated into Arabic. Some of these texts later found their way to Europe seats of learning via Moorish Spain, for example, so much so that as various schools of thought developed and led to the Enlightenment, they drew on numerous cultures, including some whose identity has been obscured. In the maturation of humanity towards willingness to embrace what has value in any culture, to view all knowledge as the patrimony of the whole race, and to regard the welfare of all as a shared responsibility, empires that have helped to build cultural bridges, such as the Seleucid Empire, have played a pivotal role.

| Seleucid dynasty Born: 358 B.C.E.; Died: 281 B.C.E. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Alexander IV, King of Asia |

Seleucid King 305–281 B.C.E. |

Succeeded by: Antiochus I Soter |

Notes

- ↑ Grainger 1990, 2.

- ↑ Appian, and Horace White trans. 1982. Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press. Livius: Articles on ancient history. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ Strabo. 1906.

- ↑ Strabo 15.2.1(9). Translated by H.C. Hamilton. London: George Bell & Sons. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ W.W. Tarn, 1951, The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge, UK: the University Press, 100.

- ↑ Pliny 1887, 50.

- ↑ Alexander Sources. v,6. Arrian Anabasis Book 5a. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Arthur Wesley Helweg, 2004, Strangers in a not-so-strange land: Indian American immigrants in the global age. Case studies in cultural anthropology. (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 9780534613129), 17.

- ↑ "And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters (as to make people more amorous). And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love." (Athenaeus and Yonge 1854, 30)

- ↑ Pliny 1847, 121.

- ↑ Head Barclay, 1911, Coinage of Seleucus and Antiochus in India. Historia Numorum. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 835. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ Mahlon H. Smith, 1999, Antiochus I Soter. Historical Sourcebook. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ William John Conybeare and J.S. Howson, 1896, The life and epistles of St. Paul. (London, UK: Longmans, Green. ISBN 9780790516431), 101.

- ↑ Edwards 2005, 97

- ↑ Dirven 1999, 122.

- ↑ Dirven 1999, 136.

- ↑ Edwards 2005, 217.

- ↑ Edwards 2005, 184.

- ↑ Edwards 2005, 190.

- ↑ Edwards. 2005, 191.

- ↑ Edwards 2005, 217-218.

- ↑ Dirven 1999, 135.

- ↑ Wilson 2006, 480.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Athenaeus, and Charles Duke Yonge. 1854. The Deipnosophists, or, Banquet of the Learned of Athenaeus. London, UK: Henry G. Bohn.

- Bar-Kochva, Bezalel. 1976. The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns. Cambridge Classical Studies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521206679.

- Dirven, Lucinda. 1999. The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: a Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World, v. 138. Boston, MA: Brill. ISBN 9789004115897.

- Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen, F.W. Walbank, John Boardman, A.E. Astin, M.W. Frederiksen, and R.M. Ogilvie. 2005. The Cambridge Ancient History Pt. 1. The Hellenistic World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 9780521234450.

- Grainger, John D. 1990. Seleukos Nikator: Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415047012.

- Pliny, and Philemon Holland. 1847. Pliny's Natural History. In thirty-Seven Books. London, UK: Printed for the Club by G. Barclay.

- Pliny, John Bostock, and Henry T. Riley. 1887. The Natural History of Pliny. Bohn's classical library. London, UK: G. Bell.

- Wilson, Nigel Guy. 2006. Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 9780415973342.

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.