Pakistani folklore

Pakistani folklore encompasses the folk songs, folktales, myths, legends, customs, proverbs and traditions of the four provinces and numerous tribal areas that make up the modern nation of Pakistan. Throughout most of the area’s history, only scholars and administrators were literate; poetry and literature were transmitted orally and folklore and folk tales offered education in religious precepts and moral values, preserved political understanding and history, and provided entertainment. Every village had hundreds of tales and traditions, faithfully repeated by parents to their children and by storytellers at festivals and public occasions. Some folklore was an essential aspect of religious practice, explaining cosmology and the significance of local shrines and deities. Pakistani folklore is shaped both by the languages and traditions of the various ethnic groups that make up the population, and by the religious convictions of the people in each region. Pakistani folklore offers valuable historical evidence of religious and ethnic migrations and of cultural influences.

Among the most popular folk tales are several love tragedies in which young lovers are thwarted by family values and social conventions and defy convention by performing acts of great daring for the sake of their love, typically resulting in the death of one or both of them. These stories reflect a double standard; the protagonists are punished by death for defying social convention, but venerated as symbols of divine love and redemption from suffering and unfulfilled desires. This theme of exceptional love thwarted by social obstacles and ultimately redeemed by some tragic event has carried over into the contemporary movies, radio and television that have overtaken story-telling as popular entertainment.

History, regions and languages

The region forming modern Pakistan was home to the ancient Indus Valley Civilization and then, successively, recipient of ancient Vedic, Persian, Indo-Greek and Islamic cultures. The area has witnessed invasions and/or settlement by the Aryans, Persians, Greeks, Arabs, Turks, Afghans, Mongols and the British.[1] Pakistani folklore contains elements of all of these cultures. The themes, characters, heroes and villains of regional folklore are often a reflection of local religious traditions, and folklore serves as both entertainment and a vehicle for transmission of moral and religious concepts and values. Some folklore performances are integral to religious rites and festivals.

Folklore is primarily an oral tradition. Each of the languages spoken in Pakistan has a unique repertoire of poems, songs, stories and proverbs associated with its cultural origins. Poetry and literature were preserved orally for centuries before being written down, transmitted from one generation of storytellers to the next. Tales of individual exploits, heroism and historical events were added to the repertoire and faithfully reproduced. The best-known Pakistani folk tales are the heroic love stories that have been immortalized by singers, storytellers and poets, and that continue to inspire modern writers and filmmakers.

Most Pakistani folktales are circulated within a particular region, but certain tales have related variants in other regions of the country or in neighboring countries. Some folktales like Shirin and Farhad are told in Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan, Turkey and almost all the nations of Central Asia and Middle East; each claims that the tale originated in their land.

Regions

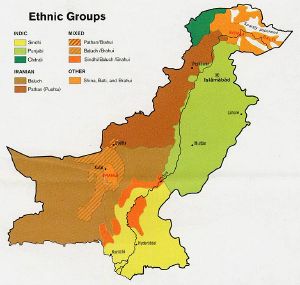

Pakistan is a federation of four provinces, a capital territory and federally administered tribal areas.

Provinces:

- 1. Balochistan

- 2. North-West Frontier Province (NWFP)

- 3. Punjab

- 4. Sindh

Territories:

- 5. Islamabad Capital Territory

- 6. Federally Administered Tribal Areas

- 7. Azad Kashmir

- 8. Northern Areas

The major languages spoken in Pakistan are:

- Punjabi 44.68 percent

- Pashto 15.42 percent

- Sindhi 14.1 percent

- Seraiki 8.38 percent

- Urdu 7.57 percent

- Balochi 3.57 percent

- Others 6.08 percent (including Pothohari, Kashmiri, Persian, Dari, Hindko, Gujrati, Memoni, Makrani, Marwari, Bangali, Gojri, and Dogri ).[2]

The religious traditions of Pakistan are:

- Islam 173,000,000 (97 percent) (nearly 70 percent are Sunni Muslims and 30 percent are Shi'a Muslims).

- Hinduism 3,200,000 (1.85 percent)

- Christianity 2,800,000 (1.6 percent)

- Sikhs Around 20,000 (0.04 percent)

Thee are much smaller numbers of Parsis, Ahmadis, Buddhists, Jews, Bahá'ís, and Animists (mainly the Kalasha of Chitral).[3]

Provincial folklore

Baloch folklore

The Baloch (بلوچ; alternative transliterations Baluch, Balouch, Bloach, Balooch, Balush, Balosh, Baloosh, Baloush) are an Iranian people and speak Balochi, which is a northwestern Iranian language. They are predominantly Muslim, and have traditionally inhabited mountainous terrains, allowing them to maintain a distinct cultural identity. Approximately 60 percent of the total Baloch population lives in Pakistan in Sindh and Southern Punjab.

Love stories such as the tales of Hani and Shah Murad Chakar, Shahdad and Mahnaz, Lallah and Granaz, Bebarg and Granaz, Mast and Sammo, are prominent in Balochi folklore. There are also many stirring tales of war and heroism on the battlefield. Baloch dance, the chap, has a curious rhythm with an inertial back sway at every forward step, and Baloch music is unique in Pakistan.

Kashmiri folklore

Most of the approximately 105,000 speakers of Kashmiri in Pakistan are immigrants from the Kashmir Valley and include only a few speakers residing in border villages in Neelum District. Kashmiri is rich in Persian words[4] and has a vast number of proverbs, riddles and idiomatic sayings that are frequently employed in everyday conversation. Folk heroes and folktales reflect the social and political history of the Kashmiri people and their quest for a society based on the principles of justice and equality.[5]

Pukhtun folklore

Pukhtuns (Pashtuns (Template:Lang-ps "Paṣtūn", "Paxtūn", also rendered as "Pushtuns," Pakhtuns, "Pukhtuns"), also called "Pathans" (Urdu: "پٹھان", Hindi: पठान Paṭhān), "ethnic Afghans",[6] are an Eastern Iranian ethno-linguistic group with populations primarily in Afghanistan and in the Northwest Frontier Province, Federally Administered Tribal Areas and Balochistan provinces of western Pakistan. They are the second-largest ethnic group in Pakistan, and are typically characterized by their usage of the Pashto language and practice of Pashtunwali, which is a traditional code of conduct and honor.[7] Pukhtun culture developed over many centuries. Pre-Islamic traditions, probably dating back to as far as Alexander's conquest in 330 B.C.E., survived in the form of traditional dances, while literary styles and music largely reflect strong influence from the Persian tradition and regional musical instruments fused with localized variants and interpretation. Pashtun culture is a unique blend of native customs and strong influences from Central, South and West Asia. Many Pukhtuns continue to rely on oral tradition due to relatively low literacy rates. Pukhtun men continue to meet at chai khaanas (tea cafes) to listen and relate various oral tales of valor and history. Despite the general male dominance of Pashto oral story-telling, Pukhtun society is also marked by some matriarchal tendencies.[8] Folktales involving reverence for Pukhtun mothers and matriarchs are common and are passed down from parent to child, as is most Pukhtun heritage, through a rich oral tradition.

Pukhtun performers remain avid participants in various physical forms of expression including dance, sword fighting, and other physical feats. Perhaps the most common form of artistic expression can be seen in the various forms of Pukhtun dances. One of the most prominent dances is Attan, which has ancient pagan roots. It was later modified by Islamic mysticism in some regions and has become the national dance of Afghanistan and various districts in Pakistan. A rigorous exercise, Attan is performed as musicians play various instruments including the dhol (drums), tablas (percussion), rubab (a bowed string instrument), and toola (wooden flute). With a rapid circular motion, dancers perform until no one is left dancing. Other dances are affiliated with various tribes including the Khattak Wal Atanrh (named after the Khattak tribe), Mahsood Wal Atanrh (which in modern times, involves the juggling of loaded rifles), and Waziro Atanrh among others. A sub-type of the Khattak Wal Atanrh known as the Braghoni involves the use of up to three swords and requires great skill. Though most dances are dominated by males, some performances such as Spin Takray feature female dancers. Young women and girls often entertain at weddings with the Tumbal (tambourine).

Traditional Pukhtun music has ties to Klasik (traditional Afghan music heavily inspired by Hindustani classical music), Iranian musical traditions, and other forms found in South Asia. Popular forms include the ghazal (sung poetry) and Sufi qawwali music. Themes include love and religious introspection.

- Yusuf Khan and Sherbano: The story, put into verse by the Pashtun poet Ali Haider Joshi (1914–2004), is about Yusuf Khan, a hunter who falls in love with the beautiful Sher Bano. Yusuf Khan's jealous cousins conspire against him. They deprive him of the legacy from his deceased father, and while he is serving in the army of King Akbar, arrange Sherbano’s betrothal to another man. Yusuf Khan arrives with a military contingent on her wedding day, avenges himself and marries his beloved. They are happy together, but when Sherbano sends him to hunt for game he is betrayed by his deceitful cousins and killed on a mountain. Sherbano rushes to his side and takes her own life.

- Adam Khan and Durkhanai: Durkhanai is a beautiful and educated girl who falls in love with Adam Khan, a lute player (rabab), when she hears his music. Adam Khan catches a glimpse of her beauty and is equally infatuated. Durkhanai is already betrothed to another suitor and is obliged to go through with the marriage, but she cannot give up her love for Adam Khan. Both of the lovers are driven mad by their love and cured by some yogis. Eventually Durkhanai’s husband releases her, but Adam Khan dies before they can be reunited. She pines away and they are buried side by side.[9]

Punjabi folklore

The Punjab region, populated by Indo-Aryan speaking peoples, has been ruled by many different empires and ethnic groups, including Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, ancient Macedonians, Persians, Arabs, Turks, Mughals, Afghans, Balochis, Sikhs and British. The main religions of the Punjab region are Sikhism, Islam and Hinduism.

Romantic tragedies

The heroines of Punjabi folk tales do not pine away, but rebel against the conventional norms of society and sacrifice everything for love. There are four popular tragic romances of the Punjab: Heer Ranjha, Mirza Sahiba, Sassi Punnun, and Sohni Mahiwal. These folktales immortalize and enshrine mortal love as the spirit of divine love. The poet Waris Shah, who versified the tale of Heer Ranjha, elevated mortal love to the same level as spiritual love for God.[10] The tales also portray a double standard of moral and social convictions and the supremacy of love and loyalty. The protagonists are punished with death for flouting social conventions and disobeying their parents, yet their deaths are glorified and offerings are made at their tombs by those who seek blessings and redemption from suffering and unfulfilled desires.

- Heer Ranjha (Punjabi: ਹੀਰ ਰਾਂਝਾ, ہیر رانجھا, hīr rāñjhā): Heer is the beautiful daughter of a wealthy Jatt family in Jhang. Ranjha, the youngest of four brothers, is his father's favorite son and leads a life of ease playing the flute ('Wanjhli'/'Bansuri'). Ranjha leaves home after a quarrel with his brothers over land, and travels to Heer's village where he is offered a job as caretaker of her father's cattle. Heer becomes mesmerized by Ranjha’s flute playing; the two fall in love and meet secretly for many years until they are caught by Heer's jealous uncle, Kaido, and her parents. Heer is engaged to marry another man, and the heartbroken Ranjha becomes a Jogi. piercing his ears and renouncing the material world. On his travels around the Punjab, Ranjha is eventually reunited with Heer, and her parents agree to their marriage. On the wedding day, Heer's jealous uncle poisons her food; Ranjha rushes to her side, takes the poisoned Laddu (sweet) which Heer has eaten and dies by her side. It is believed that the folktale originally had a happy ending, but that the poet Waris Shah (1706–1798) made it a tragedy. Heer and Ranjha are buried in a Punjabi town in Pakistan called Jhang, Punjab, where lovers and frequently visit their mausoleum.

- Mirza Sahiba (Punjabi: ਿਮਰਜ਼ਾ ਸਾਹਿਬਾਂ, مرزا صاحباں, mirzā sāhibāṁ): Mirza and Sahiban are cousins who fall in love when Mirza is sent to Sahiban’s town to study. Sahiban’s parents disapprove of the match and arrange her marriage to Tahar Khan. Sahiban sends a taunting message to Mirza in his village, Danabad, "You must come and decorate Sahiban’s hand with the marriage henna." Mirza arrives on his horse, Bakki, the night before the wedding and secretly carries Sahiba away, planning to elope. Sahiba's brothers follow and catch up with them as Mirza is resting in the shade of a tree. Knowing that Mirza is a good marksman who will surely kill her brothers, and confident that her brothers will forgive and accept him when they see her, Sahiba breaks all Mirza’s arrows before she wakes him up. Her brothers attack Mirza and kill him, and Sahiban takes a sword and kills herself.

- Sassui Punnun (or Sassui Panhu or Sassui Punhun) (Urdu: سسی پنوں; Sindhi: سسئي پنھون; Hindi: सस्सी-पुन्हू;Punjabi Gurmukhi: ਸੱਸੀ ਪੁੰਨ੍ਹੂੰ) is one of the seven popular tragic romances of the Sindh as well as one of the four most popular in Punjab. When Sassui, the daughter of the King of Bhambour, is born, astrologers predicted that she will be a curse for the royal family. The Queen orders the child to be put in a wooden box and thrown in the Indus River. A washerman of the Bhambour village finds the wooden box and adopts the child. Punnun is the son of King Mir Hoth Khan, Khan of Kicham (Kech). Stories of Sassui’s beauty reach Punnun and he becomes desperate to meet her. He travels to Bhambour and sends his clothes to Sassui's father to be washed so that he can catch a glimpse of her. Sassui and Punnun fall in love at first sight. Sassui's father agrees to the marriage, but Punnun’s father and brothers are opposed. Punnun's brothers travel to Bhambhor, kidnap Punnun on his wedding night and return to their hometown of Kicham. The next morning, Sassui, mad with the grief at being separated from her lover, runs barefoot across the desert towards the town of Kicham. On the way she is threatened by a shepherd and prays to God to hide her. The mountains open up and swallow her. Punnun, running back to Bhambhor, hears the story from the shepherd and utters the same prayer. The land splits again and he is buried in the same mountain valley as Sassui. The legendary grave still exists in this valley. Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (1689–1752) retold this tale in his Sufi poetry as an example of eternal love and union with the Divine.

- Sohni Mahiwal (Urdu/Punjabi: سوہنی مہیوال Sindhi: सोहनी महीवाल) is also popular in Sindh and across South Asia. It is one of the most prominent examples of medieval poetic legends in the Punjabi and Sindhi languages. Sohni is the daughter of a potter named Tula, who lives in Gujrat on the caravan trade route between Bukhara and Delhi.[11]She draws floral designs on her father’s 'surahis' (water pitchers) and mugs and transform them into masterpieces of art. Izzat Baig, a wealthy trader from Bukhara (Uzbekistan), is completely enchanted when he sees the beautiful Sohni and sends his companions away without him. He takes a job as a servant in the house of Tula, and Sohni falls in love with him. When they hear rumors about the love of Sohni and Mahiwal, Sohni’s parents arrange her marriage with another potter without her knowledge. His "barat" (marriage party) arrives at her house unannounced and her parents bundle her off in the doli (palanquin). Izzat Baig renounces the world and lives like a "faqir" (hermit) in a small hut across the river. Each night Sohni comes to the riverside and Izzat Baig swims across the river to meet her. When he is injured and cannot swim, Sohni begins swimming across the river each night, using a large earthenware pitcher as a float. Her husband’s sister follows her and discovers the hiding place where Sohni keeps her earthen pitcher among the bushes. The next day, the sister-in-law replaces the pitcher with an unbaked one which dissolves in the water. Sohni drowns in the river; when Mahiwal sees this from the other side of the river, he jumps into the river and drowns with her. According to the legend, the bodies of Sohni and Mahiwal were recovered from river Indus near Shahdapur and are buried there.

Riddles

Punjabis enjoy posing riddles and metaphorical questions as entertainment and as a measure of a person’s wit and intellectual capacity. Riddle competitions are mentioned in many Punjab folk-tales. It was once a common practice at weddings to assess the bridegroom’s intellect by posing riddles.[12]

Sindhi folklore

Sindhi is spoken as a first language by 14 percent of Pakistanis, in Sindh and parts of Balochistan. Sindh was conquered by Muhammad bin Qasim in 712 C.E. and remained under Arab rule for 150 years. Sindhi contains Arabic words and is influenced by Arabic language, and the folklore contains elements of Arabic legends. Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (1689–1752) (Sindhi: شاھ عبدالطيف ڀٽائيِ), a Sufi scholar and saint, is considered one of the greatest poets of the [[Sindhi language. His most famous work, the Shah Jo Risalo, is a compilation of folk tales and legends in verse. The original work was orally transmitted and became popular in the folk culture of Sindh.

The women of Shah Abdul Latif’s poetry are known as the Seven Queens (Sindhi: ست مورميون), heroines of Sindhi folklore who have been given the status of royalty in the Shah Jo Risalo. They are featured in the tales Umar Marvi (Marvi), Momal Rano (Momal) and Sohni Mahiwal (Sohni), Laila Chanesar (Laila), Sorath Rai Diyach (Heer), Sassui Punnun (Sassui), and Noori Jam Tamachi (Noori). The Seven Queens were celebrated throughout Sindh for their positive qualities: honesty, integrity, piety and loyalty. They were also valued for their bravery and their willingness to risk their lives in the name of love. Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai may have regarded them as idealized womanhood, but the Seven Queens have inspired all Sindh women to have the courage to choose love and freedom over tyranny and oppression. The lines from the Risalo describing their trials are sung at Sufi shrines all over Sindh.

- Noori Jam Tamachi (Sindhi: نوري ڄام تماچي) is the tragic story of the love between King Jam Tamachi of Unar, and Noori daughter of a fisherman (Muhana). According to the legend, Noori was buried in the Kalri Lake. Today there a mausoleum in the middle of the lake dedicated to Noori is visited by hundreds of devotees daily. The legend has been retold countless times, and is often presented as metaphor for divine love by Sufis.

Seraiki folklore

Seraiki in the south is equally rich in folklore. Seraiki is related to Punjabi and Sindhi and is spoken as a first language by 11 percent of Pakistanis, mostly in southern districts of Punjab. Over the centuries, the area has been occupied and populated from the West and North by Aryans, Persians, Greeks, Parthian, Huns, Turks and Mongols, whose cultural and linguistic traditions were absorbed and developed into a unique language rich in vocabulary. Seraiki is rich in idioms, idiomatic phrases, lullabies, folk stories, folk songs and folk literature. Folklore for children is also abundant.[13] The Seraiki language has a distinctive symbolism rooted in the beliefs and teachings of the Hindu Bhakti saints and Muslim saints. Legendary stories take place in the arid plains and stark landscapes of the Thar desert. Seraiki shares many of the Sindh and Punjabi legends, and folk tales, such as "Sassui Punnun" and "Umar Marvi," of young lovers thwarted by false family and social values, who defy convention by exceptional acts of daring, ending in tragedy.[14]

Muslim folklore

The Muslim high culture of Pakistan and rest of South Asia emphasized Arabic, Persian and Turkish culture. Islamic mythology and Persian mythology are part of Pakistani folklore. The Shahnameh, One Thousand and One Nights and Sinbad the Sailor were part of the education of Muslim children in Pakistan before English language education was imposed by the British during the 1800s.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Pakistan InfoPlease. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Government of Pakistan - National Database & Registration Authority (NADRA), NADRA Has Registered 2.15 Million Afghan Refugees, February 15, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Robert Ayres, Turning Point: The End of the Growth Paradigm, (James & James/Earthscan, 1998, ISBN 1853834394), 63.

- ↑ Krishna, Gopi (1967). Kundalini: The Evolutionary Energy in Man. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 9781570622809. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Kashmir: A folklore that fascinates BILAL AHAMAD. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Banuazizi, Ali and Myron Weiner (eds.). 1994, The Politics of Social Transformation in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (Contemporary Issues in the Middle East), (Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815626088).

- ↑ Olivier Roy, 2006, Globalized Islam: The Search For A New Ummah, (Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231134996), 261.

- ↑ The tale of the Pashtun poetess, Leela Jacinto, The Boston Globe, 22 May 2005. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Adam Khan and Durkhanai. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ LOVE LEGENDS OF PUNJAB Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Folk Tales of Pakistan: Sohni Mahiwal Pakistaniat.com Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Literature & Poetry Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Seraiki Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Seraiki language Retrieved February 4, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abbasi, Muhammad Yusuf. 1992. Pakistani Culture: A Profile. Historical studies (Pakistan) series, 7. Islamabad: National Inst. of Historical and Cultural Research. ISBN 9789694150239

- Abbas, Zainab Ghulam. 1960. Folk Tales of Pakistan. Karachi: Pakistan Publications.

- Banuazizi, Ali and Myron Weiner (eds.). 1994. The Politics of Social Transformation in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (Contemporary Issues in the Middle East), Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815626088

- Hanaway, William L., and Wilma Louise Heston. 1996. Studies in Pakistani Popular Culture. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, Lok Virsa Pub. House.

- Kamalu, Lachman, and Susan Harmer. 1990. Folk Tales of Pakistan. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education. ISBN 9780333545263

- Knowles, James Hinton. 1981. Kashmiri Folk Tales. Islamabad: National Institute of Folk Heritage.

- Korom, Frank J. 1988. Pakistani Folk Culture: A Select Annotated Bibliography. Islamabad: Lok Virsa Research Centre.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Pakistani_folklore history

- Baloch_people history

- Yusuf_Khan_and_Sherbano history

- Adam_Khan_and_Durkhanai history

- Heer_Ranjha history

- Mirza_Sahiba history

- Sassi_Punnun history

- Sohni_Mahiwal history

- Noori_Jam_Tamachi history

- Shah_Abdul_Latif_Bhita'i history

- Pakistan history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.