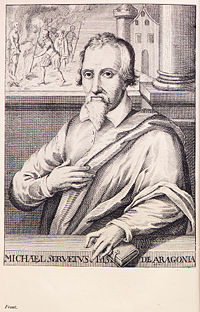

Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus (also Miguel Servet or Miguel Serveto) (September 29, 1511 – October 27, 1553) was a Spanish theologian, physician, and humanist.

His interests included many sciences: Astronomy, meteorology, geography, jurisprudence, study of the Bible, mathematics, anatomy, and medicine. He is renowned in the history of several of these fields, particularly medicine, and theology.

He participated in the Protestant Reformation, and later developed an anti-trinitarian theology. Condemned by Catholics and Protestants alike, he was burnt at the stake by order of the Geneva governing council as a heretic. His execution at the hands of Protestants did much to strengthen the case for religious liberty and for the separation of Church and state, so much so that his death may have been more significant than the ideas he espoused while alive. The role played by John Calvin was controversial at the time. Calvin almost left Geneva due to public "indignation" against him for his part in the affair.[1] Servetus' execution showed that Protestants could be just as intolerant as Catholics in dealing with those they considered to hold unacceptable religious convictions.

Early life and education

Servetus was born in Villanueva de Sijena, Huesca, Spain, in 1511 (probably on September 29, his patron saint's day), although no specific record exists. Some sources give an earlier date based on Servetus' own occasional claim of being born in 1509. His paternal ancestors came from the hamlet of Serveto, in the Aragonian Pyrenees, which gave the family their surname. The maternal line descended from Jewish Conversos (Spanish or Portuguese Jews who converted to Christianity) of the Monzón area. In 1524, his father Antonio Serveto (alias Revés, that is "Reverse"), who was a notary at the royal monastery of Sijena nearby, sent young Michael to college, probably at the University of Zaragoza or Lérida. Servetus had two brothers: One who became a notary like their father, and another who was a Catholic priest. Servetus was very gifted in languages and studied Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. At the age of fifteen, Servetus entered the service of a Franciscan friar by the name of Juan de Quintana, an Erasmian, and read the entire Bible in its original languages from the manuscripts that were available at that time. He later attended Toulouse University in 1526, where he studied law. There he became suspect of participating in secret meetings and activities of Protestant students.

In 1529, Servetus traveled through Germany and Italy with Quintana, who was then Charles V's confessor in the imperial retinue. In October 1530, he visited Johannes Oecolampadius in Basel, staying there for about ten months, and probably supporting himself as a proofreader for a local printer. By this time, he was already spreading his beliefs. In May 1531, he met Martin Bucer and Fabricius Capito in Strasbourg. Then two months later, in July, he published, De trinitatis erroribus ("On the Errors of the Trinity"). The next year, he published Dialogorum de Trinitate ("Dialogues on the Trinity") and De Iustitia Regni Christi ("On the Justice of Christ's Reign").

In these books, Servetus built a theology which maintains that the belief of the Trinity is not based on biblical teachings but rather on what he saw as deceiving teachings of (Greek) philosophers. He saw himself as leading a return to the simplicity and authenticity of the Gospels and the early Church Fathers. In part he hoped that the dismissal of the Trinitarian dogma would also make Christianity more appealing to Judaism and Islam, which had remained as strictly monotheistic religions.

Servetus affirmed that the divine Logos, which was a manifestation of God and not a separate divine Person, was united to a human being, Jesus, when God's spirit came into the womb of the Virgin Mary. Only from the moment of conception, the Son was actually generated. Therefore, the Son was not eternal, but only the Logos from which He was formed. For this reason, Servetus always rejected that Christ was the "eternal Son of God," but rather that he was simply "the Son of the eternal God." This theology, although totally original, has often been compared to Adoptionism and to Sabellianism or Modalism, which were old Christian heresies. Under severe pressure from Catholics and Protestants alike, Servetus somehow modified this explanation in his second book, Dialogues, to make the Logos coterminous with Christ. This made it nearly identical with the pre-Nicene view, but he was still accused of heresy because of his insistence on denying the dogma of the Trinity and the individuality of three divine Persons in one God.

He took on the pseudonym Michel de Villeneuve ("Michael from Villanueva"), in order to avoid persecution by the Church because of these religious works. He studied at the College Calvi in Paris, in 1533. After an interval, he returned to Paris to study medicine, in 1536. There, his teachers included Sylvius, Fernel, and Guinter, who hailed him with Vesalius as his most able assistant in dissections.

Career

After his studies in medicine, he started a medical practice. He became personal physician to Archbishop Palmier of Vienne, and was also physician to Guy de Maugiron, the lieutenant governor of Dauphiné. While he practiced medicine near Lyon for about fifteen years, he also published two other works dealing with Ptolemy's Geography. Servetus dedicated his first edition of Ptolemy and his edition of the Bible to his patron Hugues de la Porte, and dedicated his second edition of Ptolemy's Geography to his other patron, Archbishop Palmier. While in Lyon, Symphorien Champier, a medical humanist, had been Servetus' patron, and the pharmacological tracts which Servetus wrote there were written in defense of Champier against Leonard Fuchs.

While also working as a proof reader, he published a couple more books which dealt with medicine and pharmacology. Years earlier, he had sent a copy to John Calvin, initiating a correspondence between the two. In initial correspondence, Servetus used the pseudonym "Michel de Villeneuve."

In 1553, Servetus published yet another religious work with further Antitrinitarian views. It was entitled, Christianismi Restitutio, a work that sharply rejected the idea of predestination and the idea that God had condemned souls to Hell regardless of worth or merit. God, insisted Servetus, condemns no one who does not condemn himself through thought, word, or deed. To Calvin, who had written the fiery, Christianae religionis institutio, Servetus' latest book was a slap in the face. The irate Calvin sent a copy of his own book as his reply. Servetus promptly returned it, thoroughly annotated with insulting observations.

Calvin wrote to Servetus, "I neither hate you nor despise you; nor do I wish to persecute you; but I would be as hard as iron when I behold you insulting sound doctrine with so great audacity."

In time, their correspondences grew more heated, until Calvin ended it.[2] Whereupon Servetus bombarded Calvin with a slew of extraordinarily unfriendly letters.[3] Calvin developed a bitter hatred based not only on the unorthodox views of Servetus but also on Servetus's tone of superiority mixed with personal abuse. Calvin stated of Servetus, when writing to his friend William Farel on February 13, 1546:

Servetus has just sent me a long volume of his ravings. If I consent he will come here, but I will not give my word for if he comes here, if my authority is worth anything, I will never permit him to depart alive

("Si venerit, modo valeat mea autoritas, vivum exire nunquam patiar").[4]

Imprisonment and execution

On February 16, 1553, Servetus, while in Vienne, was denounced as a heretic by Guillaume Trie, a rich merchant who took refuge in Geneva and a very good friend of Calvin,[5] in a letter sent to a cousin, Antoine Arneys, living in Lyon. On behalf of the French inquisitor, Matthieu Ory, Servetus as well as Arnollet, the printer of Christianismi Restitutio, were questioned, but they denied all charges and were released for lack of evidence. Arneys was asked by Ory to write back to Trie, demanding proof.

On March 26, 1553, the book and the letters sent by Servetus to Calvin were forwarded to Lyon by Trie.

On April 4, 1553, Servetus was arrested by the Roman Catholic authorities, and imprisoned in Vienne. He escaped from prison three days later. On June 17, he was convicted of heresy by the French inquisition, and sentenced to be burned with his books. An effigy and his books were burned in his absence.

Meaning to flee to Italy, Servetus stopped in at Geneva, where Calvin and his Reformers had denounced him. On August 13, he attended a sermon by Calvin at Geneva. He was immediately recognized and arrested after the service[6] and was again imprisoned and had all his property confiscated.

Unfortunately for Servetus, at this time, Calvin was fighting to maintain his weakening power in Geneva. Calvin's delicate health and usefulness to the state meant he did not personally appear against Servetus.[7] Also, Calvin's opponents used Servetus as a pretext for attacking the Geneva Reformer's theocratic government. It became a matter of prestige for Calvin to be the instigator of Servetus's prosecution. "He was forced to push the condemnation of Servetus with all the means at his command." However, Nicholas de la Fontaine played the more active role in Servetus's prosecution and the listing of points that condemned him.

At his trial, Servetus was condemned on two counts, for spreading and preaching Nontrinitarianism and anti-paedobaptism (anti-infant baptism).[8] Of paedobaptism, Michael Servetus had said, "It is an invention of the devil, an infernal falsity for the destruction of all Christianity."[9] Whatever the cause of them, be it irritation or mistreatment, his statements that common Christian traditions were "of the devil" severely harmed his ability to make allies. Nevertheless, Sebastian Castellio denounced his execution and became a harsh critic of Calvin due to the whole affair.

Although Calvin believed Servetus deserving of death on account of his "execrable blasphemies," he nevertheless hoped that it would not be by fire, as he was inclined toward clemency.[10] Calvin expressed these sentiments in a letter to Farel, written about a week after Servetus’ arrest, in which he also mentions an exchange between himself and Servetus. Calvin writes:

…after he [Servetus] had been recognized, I thought he should be detained. My friend Nicolas summoned him on a capital charge, offering himself as a security according to the lex talionis. On the following day he adduced against him forty written charges. He at first sought to evade them. Accordingly we were summoned. He impudently reviled me, just as if he regarded me as obnoxious to him. I answered him as he deserved… of the man’s effrontery I will say nothing; but such was his madness that he did not hesitate to say that devils possessed divinity; yea, that many gods were in individual devils, inasmuch as a deity had been substantially communicated to those equally with wood and stone. I hope that sentence of death will at least be passed on him; but I desired that the severity of the punishment be mitigated.[11]

As Servetus was not a citizen of Geneva, and legally could at worst be banished, they had consulted with other Swiss cantons (Zurich, Bern, Basel, Schaffhausen), which universally favored his condemnation and execution.[12] In the Protestant world, Basel banned the sale of his book. Martin Luther condemned his writing in strong terms. Servetus and Philip Melanchthon had strongly hostile views of each other. Most Protestant Reformers saw Servetus as a dangerous radical, and the concept of religious freedom did not really exist yet. The Catholic world had also imprisoned him and condemned him to death, which apparently spurred Calvin to equal their rigor. Those who went against the idea of his execution, the party called "Libertines," drew the ire of much of Christendom. On October 24, Servetus was sentenced to death by burning for denying the Trinity and infant baptism. When Calvin requested that Servetus be executed by decapitation rather than fire, Farel, in a letter of September 8, chided him for undue leniency,[13] and the Geneva Council refused his request. On October 27, 1553, Servetus was burned at the stake just outside Geneva. Historians record his last words as: "Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have mercy on me."[14]

Calvin tried to justify the use of such harsh punishments, not only against Servetus, but against heretics in general when he wrote:

Whoever shall maintain that wrong is done to heretics and blasphemers in punishing them makes himself an accomplice in their crime and guilty as they are. There is no question here of man's authority; it is God who speaks, and clear it is what law he will have kept in the church, even to the end of the world. Wherefore does he demand of us a so extreme severity, if not to show us that due honor is not paid him, so long as we set not his service above every human consideration, so that we spare not kin, nor blood of any, and forget all humanity when the matter is to combat for His glory.[15]

Modern relevance

Due to his rejection of the Trinity and eventual execution by burning for heresy, Servetus is often regarded as the first Unitarian martyr. Since the Unitarians and Universalists have joined in the United States, and changed their focus, his ideas are no longer very relevant to modern Unitarian Universalism. A few scholars insist he had more in common with Sabellianism or Arianism or that he even had a theology unique to himself. Nevertheless, his influence on the beginnings of the Unitarian movement in Poland and Transylvania has been confirmed by scholars,[16] and two Unitarian Universalist congregations are named after him, in Minnesota and Washington. A church window is also dedicated to Servetus at the First Unitarian Congregational Society of Brooklyn, NY.

Servetus was the first European to describe pulmonary circulation, although it was not widely recognized at the time, for a few reasons. One was that the description appeared in a theological treatise, Christianismi Restitutio, not in a book on medicine. Further, most copies of the book were burned shortly after its publication in 1553. Three copies survived, but these remained hidden for decades. It was not until William Harvey's dissections, in 1616, that the function of pulmonary circulation was widely accepted by physicians. In 1984, a Zaragoza public hospital changed its name from José Antonio to Miguel Servet. It is now a university hospital.

Notes

- ↑ Servetus International Society, Detail on the Trial and Execution of Servetus. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ↑ R.K. Downton, An Examination of the Nature of Authority. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ↑ Will Durant, The Story of Civilization: The Reformation, p. 481.

- ↑ Ibid., 2.

- ↑ Bainton, Hunted Heretic, p. 103.

- ↑ The Heretics, p. 326.

- ↑ Merrick Whitcomb, ed., "The Complaint of Nicholas de la Fontaine Against Servetus, 14 August, 1553," in Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European History (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania History Department, 1898-1912).

- ↑ Hunted Heretic, p. 141.

- ↑ Hugh Young Reyburn, John Calvin: His Life, Letters, and Work (New York: Hodder and Stoughton, 1914), p. 175. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ↑ Robert Dale Owen, The Debatable Land Between this World and the Next (New York: G.W. Carleton & Co., 1872), p. 69.

- ↑ Calvin, Letters of John Calvin (Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth Trust, 1980), p. 158–159. ISBN 0-85151-323-9

- ↑ The History & Character of Calvinism, p. 175.

- ↑ The History & Character of Calvinism, p. 176.

- ↑ Peter Kurth, Review of Out of the Flames by Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ↑ John Marshall, John Locke, Toleration and Early Enlightenment Culture (Cambridge University Press, 2006). ISBN 0-521-65114-X

- ↑ Stanislas Kot, "L'influence de Servet sur le mouvement atitrinitarien en Pologne et en Transylvanie," in B. Becker (Ed.), Autour de Michel Servet et de Sebastien Castellion (Haarlem, 1953).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bainton, Roland H. Hunted Heretic: The Life and Death of Michael Servetus 1511–1553. Gloucester, MA: P. Smith, 1978. ISBN 9780844615806.

- Calvin, Jean. Defensio orthodoxae fidei de sacra Trinitate contra prodigiosos errores Michaelis Serveti… (Defense of Orthodox Faith against the Prodigious Errors of the Spaniard Michael Servetus…). Geneva, 1554.

- Calvin, Jean and Jules Bonnet. Letters of John Calvin: Selected from the Bonnet Edition with an Introductory Biographical Sketch. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1980. ISBN 9780851513232.

- Goldstone, Lawrence and Nancy. Out of the Flames: The Remarkable Story of a Fearless Scholar, a Fatal Heresy, and One of the Rarest Books in the World. New York: Broadway Books, 2002. ISBN 0-7679-0837-6.

- McNeill, John T. The History and Character of Calvinism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954. ISBN 0-19-500743-3.

- Nigg, Walter. The Heretics: Heresy Through the Ages. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1962. ISBN 0-88029-455-8.

- Simpson, William. The Man from Mars: His Morals, Politics and Religion. San Francisco: E.D. Beattle, 1900.

External links

All links retrieved May 31, 2025.

- The John Calvin and Michael Servetus Debacle

- Hanover text on the complaints against Servetus

- Servetus: His Life. Opinions, Trial, and Execution.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.