Hula

Hula (IPA: /ËhuËlÉ/) is a dance form accompanied by chant or song. It was developed in the Hawaiian Islands by the Polynesians who originally settled there beginning around in around the fifth century C.E. The chant or song that accompanies the dance is called a mele. The hula either dramatizes or comments on the mele. There are many styles of hula. They are commonly divided into two broad categories: Ancient hula, as performed before Western encounters with HawaiÊ»i, is called kahiko. It is accompanied by chant and traditional instruments. Hula as it evolved under Western influence, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, is called Ê»auana. It is accompanied by song and Western-influenced musical instruments such as the guitar, the Ê»ukulele, and the double bass.

Hula has a long history with the Hawaiian peoples, but was almost eradicated in the nineteenth century, when Protestant missionaries saw it as lewd and attempted to stamp it out. It became popular as a secular dance form in the early part of the twentieth century, but rediscovered its religious footing after the 1970s and the Hawaiian Renaissance. Hula, like many forms of dance, is an expression of much more than simply body language, and in its movements and chants can be found the history, culture, and, some say, the soul of the Hawaiian people.

Overview

Hula is a very expressive form of dance, and every movement has a specific meaning. Every movement of the dancer's hands has great significance. Chants, or mele, accompany the movements, aiding in the illustrating the narrative and telling the story. Traditional dances focused more on these chants than on hand gestures, but because so few people understand the language any longer, the emphasis is changing.[1]

Hula dancers were traditionally trained at schools called halau hula. Students followed elaborate rules of conduct known as kapu, which included obedience to their teacher, who was referred to as a kamu. Dancers were not allowed to cut their hair or nails, certain foods were forbidden and sex was not allowed. A head pupil was chosen by the students and placed in charge of discipline. A memorizer, or a hoopaa, assisted students with the chanting and drumming. The organization of today's halau hula is similar to that of the traditional schools.[1]

Hula performed today can generally be divided into two styles. The divergence of the two is generally marked as 1893, the year the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown.[2] The dances from before 1893 are are known as kahiko, or ancient hula, and the newer dancers are referred to as auana, or modern and unrestricted hula. The footwork of the two styles is nearly identical, but themes of auana tend to be more generic and lighthearted. Another difference is that the Auana dances are secular, whereas kahiko is still considered to be sacred.[2]

History of hula

The hula's origins are closely tied to Hawaiian culture. While there is little doubt that the dance originated on the Hawaiian islands, little evidence remains of the genesis of the art form. There is no record of the first person to dance the hula, although it is commonly agreed amongst Hawaiians that the first to dance were gods or goddesses. This is why the hula is held sacred by Hawaiians, and has historically been performed by both men and women.[3] The dance was developed by the Hawaiian islands' original Polynesian settlers, who used canoes from the southeastern Pacific islands to migrate to Hawaii, beginning in the fifth century, C.E.[4]

The origins of hula are often described in terms of legends. According to one legend, Laka, goddess of the hula, gave birth to the dance on the island of Moloka, at a sacred place in Kaokinaana. After she died, Laka's remains were hidden beneath the hill of Puokinau Nana. Another story states that when Pele, the goddess of fire, was trying to find a home for herself, running away from her sister Namakaokaha'i (the goddess of the oceans), she found an island where she couldn't be touched by the waves. There at chain of craters on the island of Hawai'i she danced the first dance of hula, signifying that she finally won. Yet, another such story described the efforts of Hi'iaka, the patron goddess of Hawaii, who danced to appease Pele, the Hawaiian volcano goddess and Hi'iaka's sister. This narratives provides the basis for many modern dances.[4] This tradition continued throughout the pre-European period in Hawaii, as the hula became closely related to religious practices. Offerings were made regularly to Laka and Hi'iaka.

During the nineteenth century

American Protestant missionaries, who arrived in Hawaii in 1820, denounced the hula as a heathen dance, nearly destroying it. The newly Christianized aliÊ»i (Hawaiian royalty and nobility) were urged to ban the hulaâwhich they did. Teaching and performing the hula, thus, went underground.

The Hawaiian performing arts had a resurgence during the reign of King David KalÄkaua (1874â1891), who encouraged the traditional arts. King Kalakaua requested performances of hula at his court, encouraging the traditional arts over the objections of the Christianized Hawaiians and the missionaries there.[4] Hula practitioners merged Hawaiian poetry, chanted vocal performance, dance movements, and costumes to create a new form of hula, the hula kuÊ»i (kuÊ»i means "to combine old and new"). The pahu, a sacred drum, appears not to have been used in hula kuÊ»i, evidently because its sacredness was respected by practitioners; the ipu gourd (Lagenaria sicenaria) was the indigenous instrument most closely associated with hula kuÊ»i.

Ritual and prayer surrounded all aspects of hula training and practice, even as late as the early twentieth century. Teachers and students were dedicated to the goddess of the hula, Laka.

Twentieth century hula

Hula changed drastically in the early twentieth century, as it was featured in tourist spectacles, such as the Kodak hula show, and in Hollywood films. Certain concessions were made in order to capture the imagination of outsiders, such as English language lyrics, less allusive pictorial gestures, and heightened sex appeal added by emphasizing hip movements.[4] This more entertaining hula was also more secularized, moving away from its religious context. During this time, practitioners of the more traditional form of hula were confined to a few small groups, performing quietly and without fanfare. There has been a renewed interest in hula, both traditional and modern, since the 1970s and the Hawaiian Renaissance.

This revival owed a particularly large debt Ma'iki Aiu Lake, a hula teacher trained by Lokalia Montgomery (1903-1978), a student of Mary Kawena Pukui. In the early 1970s, Lake departed from the usual tradition of training only dancers and spent three years training hula teachers in the ancient hula kahiko dances. As these new teachers began gathering students, hula was able to expand much more quickly, and has remained strong ever since.[4] In the 1990s, hula dancers were generally anonymous, known more by the names of their schools and teachers.

Today, there are several hundred hula schools, as well as many other active formal hula groups, on all the Hawaiian islands.[1] There are schools that teach both forms of hula, and, as is the case with many forms of dance, there are often public recitals. The crowning competition for hula dancers take place at modern hula festivals.

Varieties of hula

Hula kahiko (Hula ʻOlapa)

Hula kahiko encompassed an enormous variety of styles and moods, from the solemn and sacred to the frivolous. Many hula were created to praise the chiefs and performed in their honor, or for their entertainment.

Serious hula was considered a religious performance. As was true of ceremonies at the heiau, the platform temple, even a minor error was considered to invalidate the performance. It might even be a presage of bad luck or have dire consequences. Dancers who were learning to do such hula necessarily made many mistakes. Hence they were ritually secluded and put under the protection of the goddess Laka during the learning period. Ceremonies marked the successful learning of the hula and the emergence from seclusion.

Hula kahiko is performed today to the accompaniment of historical chants. Many hula kahiko are characterized by traditional costuming, by an austere look, and a reverence for their spiritual roots.

Chants

Hawaiian history was oral history. It was codified in genealogies and chants, which were memorized strictly as they were passed down. In the absence of a written language, this was the only available method of ensuring accuracy. Chants told the stories of creation, mythology, royalty, and other significant events and people of the islands.

Instruments and implements

- Ipuâsingle gourd drum

- Ipu hekeâdouble gourd drum

- Pahuâsharkskin covered drum; considered sacred

- PÅ«niuâsmall knee drum made of a coconut shell with fish skin (kala) cover

- Ê»IliÊ»iliâwater-worn lava stone used as castanets

- Ê»UlÄ«Ê»ulÄ«âfeathered gourd rattles

- PÅ«Ê»iliâsplit bamboo sticks

- KÄlaÊ»auârhythm sticks

The dog's-tooth anklets sometimes worn by male dancers could also be considered instruments, as they underlined the sounds of stamping feet.

Attire

Traditional female dancers wore the everyday pÄʻū, or wrapped skirt, but were topless. Today this form of dress has been altered. As a sign of lavish display, the pÄʻū might be much longer than the usual length of kapa,[5] a local cloth made by pounding together strips of mulberry bark, then painting and embossing it with geometric designs. Sometimes, the dancers wear very long strips of kapa, long enough to circle the waist a number of times, increasing their circumference substantially. Dancers might also wear decorations such as necklaces, bracelets, and anklets, as well as many lei, garlands of flowers, leaves, shells or other objects, (in the form of headpieces, necklaces, bracelets, and anklets).

Traditional male dancers wore the everyday malo, or loincloth. Again, they might wear bulky malo made of many yards of kapa. They also wore necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and lei.

The materials for the lei worn in performance were gathered in the forest, after prayers to Laka and the forest gods had been chanted.

The lei and kapa worn for sacred hula were considered imbued with the sacredness of the dance, and were not to be worn after the performance. Lei were typically left on the small altar to Laka found in every hÄlau, as offerings.

Performances

Hula performed for spontaneous daily amusement or family feasts were attended with no particular ceremony. However, hula performed as entertainment for chiefs were anxious affairs. High chiefs typically traveled from one place to another within their domains. Each locality had to house, feed, and amuse the chief and his or her entourage. Hula performances were a form of fealty, and often of flattery to the chief. There were hula celebrating his lineage, his name, and even his genitals (hula maʻi). Sacred hula, celebrating Hawaiian gods, were also danced. It is important that these performances be completed without error (which would be both unlucky and disrespectful).

Visiting chiefs from other domains would also be honored with hula performances. This courtesy was often extended to important Western visitors, who left many written records of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century hula performances.

Hula ʻauana

The newer hula ʻauana arose from adaptation of traditional hula ideas (dance and mele) to Western influences. The primary influences were Christian morality and melodic harmony. Hula ʻauana still tells or comments on a story, but the stories may include events more recent than the 1800s. The costumes of the women dancers are less revealing and the music is heavily Western-influenced.

Songs

The mele of hula ʻauana are generally sung as if they were popular music. A lead voice sings in a major scale, with occasional harmony parts. The range of subject of the songs is as broad as the range of human experience. People write mele hula ʻauana to comment on significant people, places, or events, or simply to express an emotion or idea. The hula then interprets the mele in dance.

Instruments

The musicians performing hula ʻauana will typically use portable acoustic stringed instruments.

- Ê»Ukuleleâfour-, six-, or eight-stringed, used to maintain the rhythm if there are no other instruments

- Guitarâused as part of the rhythm section, or as a lead instrument

- Steel guitarâaccents the vocalist

- Bassâmaintains the rhythm

Occasional hula ʻauana call for the dancers to use props, in which case they will use the same instruments as for hula kahiko.

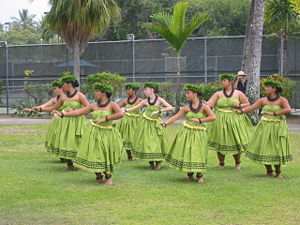

Attire

Costumes play a role in illustrating the hula instructor's interpretation of the mele. While there is some freedom of choice, most hÄlau follow the accepted costuming traditions. Women generally wear skirts or dresses of some sort. Men may wear long or short pants, skirts, or a malo (a cloth wrapped under and around the crotch). For slow, graceful dances, the dancers will wear formal clothing such as a muÊ»umuÊ»u, a long flowing dress with short gathered sleeves, for the women and a sash for men. A fast, lively, "rascal" song will be performed by dancers in more revealing or festive attire. The Hula is most always performed in bare feet.

Performances

Hula is performed at luau (Hawaiian parties) and celebrations. Hula lessons are common for girls from ages 6â12 and, just like any other kind of dance they have recitals and perform at luau.

Hula arm movements tell a story

Gallery

Contemporary hula festivals

- Ka Hula Piko, held every May on Molokaʻi.

- Merrie Monarch Festival is a week-long cultural festival and hula competition in Hilo on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi. It is essentially the Super Bowl of hula.

- Hula Workshop Ho'ike and Hawaiian Festival], held every July in Vancouver, WA.[6]

- E Hula Mau, held every Labor Day Weekend (September) in Long Beach, CA.

- World Invitational Hula Festival, a three-day art and culture contest held every November on Oahu, Hawaii in the Waikiki Shell.

- "Share da Aloha," held in February at Saddleback Church in Lake Forest, CA.[7]

- The IÄ 'Oe E Ka LÄ Hula Competition and Festival is held annually at the Alameda County Fairgrounds in Pleasanton, California. Friday through Sunday, traditionally the first weekend in November.[8]

- The May Day Festival is held annually at the Alameda County Fairgrounds in Pleasanton, California. Traditionally the second Saturday in May, as of 2006 held both Saturday and Sunday remaining the second weekend in May.[9]

Films

- Kumu Hula: Keepers of a Culture (1989). Directed by Robert Mugge.

- Holo Mai Pele - HÄlau Å Kekuhi (2000) Directed by Catherine Tatge

- American Aloha : Hula Beyond Hawaiʻi (2003) By Lisette Marie Flannery & Evann Siebens[10]

- Hula Girls (2006) Japanese film directed by Sang-il Lee.

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 1.2 Alternative Hawaii, Hawaiian Hula. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- â 2.0 2.1 David Choo, The Art of the Hula. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- â Bill McKenzie, History of the Hawaiian Hula Dance.

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Paul Waters, Hula in Hawaii,from International Encyclopedia of Dance, Hawaiian Learning Center. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- â Kapa is similar to tapa, the barkcloth found in other Polynesian cultures, such as Tonga and Samoa.

- â Aloha!, Kaleinani o ke Kukui. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- â Welcome, Ohana ke Akua. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- â Kumu Hula Association, Kumu Hula Association. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- â Kumu Hula Association, Kumu Hula Association. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- â American Aloha : Hula Beyond HawaiÊ»i (2003) By Lisette Marie Flannery & Evann Siebens Retrieved August 18, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Emerson, Nathaniel Bright. Pele and Hiiaka: A myth from Hawaii. Rutland, VT: C.E. Tuttle, 1978. ISBN 978-0804812511.

- Kane, Herb Kawainui. Pele the Goddess of Hawaii's Volcanoes. Captain Cook, HI: Kawainui Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0943357010

- Ramelb, Carol. The Hawaiian Hula. Honolulu, HI: W.W. Distributors, 1976. OCLC 6166070

External links

All links retrieved July 19, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.