German colonial empire

The German colonial empire was an overseas area formed in the late nineteenth century as part of the Hohenzollern dynasty's German Empire. Short-lived colonial efforts by individual German states had occurred in preceding centuries, but Imperial Germany's colonial efforts began in 1883. The German colonial empire ended with the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 following World War I when its territories were confiscated and distributed to the victors under the new system of mandates set up by the League of Nations. Initially reluctant to enter the race for colonies because of its tradition of expansion within the European space, Germany's renewed attempt to conquer Europe in World War I resulted in loss of its overseas possessions. At various times, Germany (as the Holy Roman Empire) had included Northern Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Holland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, what is now the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Belgium and parts of Poland. Parallels have been made between use of death camps during the revolt in German West Africa 1904-1905 and Adolf Hitler's "final solution" to what he called the "Jewish problem." The colonial territories were ruled in the same way that Germany was governed, more or less from the top down. On the other hand, Germany's disengagement from colonialism took place in such a way that protracted wars of independence were avoided. Germany's history in the twentieth century resulted in reflection on the colonial experience receiving less attention than it has had in other former colonial powers. Instead, Germany's role in two World Wars and the Holocaust has dominated thinking in terms of re-negotiating national identity.

German Empire

Owing to its delayed unification by land-oriented Prussia in 1871, Germany came late to the imperialist scramble for remote colonial territoryâtheir so-called "place in the sun." The German states prior to 1870 had retained separate political structures and goals, and German foreign policy up to and including the age of Otto von Bismarck concentrated on resolving the "German question" in Europe and securing German interests on that same continent. On the other hand, Germans had traditions of foreign sea-borne trade dating back to the Hanseatic League; a tradition existed of German emigration (eastward in the direction of Russia and Romania and westward to North America); and North German merchants and missionaries showed lively interest in overseas lands.

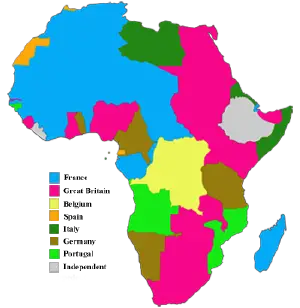

Many Germans in the late nineteenth century viewed colonial acquisitions as a true indication of having achieved nationhood, and the demand for prestigious colonies went hand-in-hand with dreams of a High Seas Fleet, which would become reality and be perceived as a threat by the United Kingdom. Initially, Bismarckâwhose Prussian heritage had always regarded Europe as the space in which German imperialist ambition found expressionâopposed the idea of seeking colonies. He argued that that the burden of obtaining and defending them would outweigh the potential benefits. During the late 1870s, however, public opinion shifted to favor the idea of a colonial empire. During the early 1880s, Germany joined other European powers in the âScramble for Africa.â Among Germany's colonies were German Togoland (now part of Ghana and Togo), Cameroon, German East Africa (now Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania), and German South-West Africa (now Namibia). The Berlin Conference of 1884-85, which Bismarck organized, established regulations for the acquisition of African colonies; in particular, it protected free trade in certain parts of the Congo River.

Because Germany was so late to join the race for colonial territories, most of the world had already been carved up by the other European powers; in some regions the trend was already towards decolonization, especially in the continental Americas, encouraged by the American Revolution, French Revolution, and Napoleon Bonaparte. In the Scramble for Africa, Germany lagged behind smaller and less-powerful nations, so that even Italy's colonial empire was larger. Geography helped Italy, whose African possessions, like France's, started immediately to the South of Italy across the Mediterranean. 1883 was late in the day to enter the colonial race.

Colonial Polity

Germany did not attempt to re-mold its colonial subjects in the German image in the way that the French and the British tried to mold their subjects in their image. While the French and the English instituted policies that spread their languages and culture, Germany restricted use of German to a small number of elite colonial subjects. Germany did not actually profit from colonialism, since the expenses incurred in administration were greater than revenues generated. Colonies were regarded as overspill for German settlers, rather than as territories to be developed and eventually granted autonomy, or independence. In fact, only small numbers of Germans relocated to the colonies. Rebellions when they took place were brutally crushed. The most well-known incident of rebellion took place in German South West Africa (now Namibia), where, when the Herero people rose in rebellion (known as the Maji-Maji rebellion) in 1904, they were crushed by German troops; tens of thousands of natives died during the resulting genocide. Parallels have been made between use of death camps and concentration camps during this period, and those of the Third Reich in its effort to exterminate the Jewish people.[1]

End of the Colonial Empire

Germany's defeat in World War I resulted in the Allied Powers dissolving and re-assigning the empire, mainly at and its subsequent peace at the Paris Peace Conference (1919).

In the treaties Japan gained the Carolines and Marianas, France gained Cameroons, Belgium gained small parts of German East Africa, and the United Kingdom gained the remainder, as well as German New Guinea, Namibia, and Samoa. Togoland was divided between France and Britain. Most of these territories acquired by the British were attached to its various Commonwealth realms overseas and were transferred to them upon their independence. Namibia was granted to South Africa as a League of Nations mandate. Western Samoa was run as a class C League of Nations mandate by New Zealand and Rabaul along the same lines by Australia. This placing of responsibility on white-settler dominions was at the time perceived to be the cheapest option for the British government, although it did have the bizarre result of British colonies having their own colonies. This outcome was very much influenced by W.M. Hughes, the Australian Prime Minister, who was astounded to find that the big four planned to give German New Guinea to Japan. Hughes insisted that New Guinea would stay in Australian hands, with the troops there defending it by force if necessary. Hughes achievement in preventing Japan occupying New Guinea was of vital importance in World War II.

William II, German Emperor, was so frustrated by the defeat of his European generals that he declared that Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, the German general in charge in East Africa, should be the only German officer allowed to lead his soldiers in a victory parade through the Brandenburg Gate. Vorbeck was the only undefeated German general of the war, and the only one to set foot in British territory.

Extent of the Empire

This is a list of former German Empire colonies and protectorates (German: Schutzgebiete), the German colonial empire.

Welser colonies

America

- Little Venice (Klein Venedig) (see German colonization of the Americas)

Brandenburger-Prussian colonies

Africa

- GroĂ Friedrichsburg (in Ghana), 1683â1718

- Arguin (in Mauretania), 1685â1721

- Whydah, in present Togo ca. 1700 (this Brandenburg 'colony' was just a minor point of support, a few dwellings at a site where British and Dutch had theirs too)

America

- Saint Thomas (Caribbean, now in the United States Virgin Islands), brandenburg Lease territory in the Danish West Indies; 1685â1720

- Island of Crabs/Krabbeninsel (Caribbean, now in USA), brandenburgische Annexion in the Danish West Indies; 1689â1693

- Tertholen (Caribbean sea; 1696)

German imperial colonies

Africa

- German East Africa - (Deutsch-Ostafrika)

- Tanganyika; after World War I a British League of Nations mandate, which in 1962 became independent and in 1964 joined with former British protectorate of the sultanate of Zanzibar to form present-day Tanzania

- Ruanda-Urundi: 1885 â 1917

- Wituland 1885 â 1890, since in Kenya

- Kionga Triangle, since 1920 (earlier occupied) in Portuguese Mozambique

- German South West Africa - (Deutsch-SĂŒdwestafrika)

- Namibia (present-day) except then-British Walvis Bay (Walvisbaai)

- Botswana - (SĂŒdrand des Caprivi-Zipfels)

- German West Africa (Deutsch-Westafrika) - existed as one unit only for two or three years, then split into two colonies due to distances:

- Kamerun 1884 â 1914; after World War I separated in a British part, Cameroons, and a French Cameroun, which became present Cameroon. The British part was later split in half, with one part joining Nigeria and the other Cameroon. (Kamerun, Nigeria-Ostteil, Tschad-SĂŒdwestteil, Zentralafrikanische Republik-Westteil, Republik Kongo-Nordostteil, Gabun-Nordteil)

- Togoland 1884 â 1914; after World War I separated into two parts: a British part (Ghana-Westteil), which joined Ghana, and a French one, which became Togo

- Mysmelibum, which became part of the Congo

Pacific

- German New Guinea (Deutsch-Neuguinea, today Papua-New-Guinea; 1884 â 1914)

- Kaiser-Wilhelmsland

- Bismarck Archipelago (Bismarck-Archipel)

- German Solomon Islands or Northern Solomon Islands (Salomonen or Nördliche Salomon-Inseln, 1885â1899)

- Bougainville (Bougainville-Insel, 1888â1919)

- Nauru (1888â1919)

- German Marshall Islands (Marshallinseln; 1885â1919)

- Mariana Islands (Marianen, 1899â1919)

- Caroline Islands (Karolinen, 1899 â 1919)

- Federated States of Micronesia (Mikronesien, 1899â1919)

- Palau (1899â1919)

- German Samoa (German Western Samoa, or Western Samoa; 1899-1919/45)

- Samoa (1900-1914)

China

- Jiaozhou Bay (1898-1914)

Other

- Hanauish Indies (de:Hanauisch Indien)

- Southern Brazil

- Ernst ThÀlmann Island

- New Swabia was a part of Antarctica, claimed by Nazi Germany (19 January 1939 - 25 May 1945), but not effectively colonized; the claim was completely abandoned afterward

- German Antarctic stations

- Georg von Neumayer station (1981-1993)

- Neumayer Station (1993-present)

- Filchner station(1982-1999)

- Gondwana station (1983-present)

- Georg Forster station (1985-present)

- Drescher station (1986-present)

- Dallmann Laboratory (1994-present)

- Kohnen Station (2001-present)

- Georg von Neumayer station (1981-1993)

- German Arctic stations

- Koldewey station, Spitsbergen (1991-present)

Legacy

The German colonial empire was relatively short-lived and has been overshadowed in the German consciousness by two world wars, followed by partition, the Cold War and more recently by re-unification. In 2005, when the centenary of the mass killings that took place in Namibia, Germans were reminded of their colonial legacy and of parallels which have been made between aspects of that legacy and the Third Reich. Dr Henning Melber comments that:

As evidence shows, there existed continuities in accounts and novels read by a mass readership, in military practice as well as in the activities of specific persons, and in doctrines and routines of warfare that link strategic ideas of decisive battles to the concept of final solution and extinction of the enemy, which came into full effect under the Nazi regime.[2]

On the other hand, the way in which Germany lost her colonial empire meant that Germany did not become engaged in the type of violent anti-independence wars that took place under the imperial watch of some other European colonial powers. Unlike the imperial legacies of other European countries, especially Spain, France and Great Britain, the German empire did not create a large German speaking community or enduring cultural links. One consequence is that "there are apparently no post-colonial texts in German." Germany preferred to keep the number of "literate natives small" and indeed did not embark on the same type of Frenchification or Anglicization project that characterized French and British imperialism. Germany's older heritage of empire within the European space secured German as a major European language but it did not spread across the globe. No non-European country has made German an official language. In contrast, French is an official language in 28 countries spread across the globe. Germany's traditional policy of restricting citizenship to people of German descent, too, has meant that until recently Germany's "immigrant population" has not amassed sufficient political power to "force German politicians to attend to their interests and needs."[3] Friedrichsmeyer, et al argue that the legacy of how German colonialism and "colonial fantasies affected notions of Germanness and national identity" and of "others" is a neglected field. While "a significant portion of French and British cosmopolitanism is due to their colonial history and their laboriously achieved disengagement from it," the "corresponding background is missing in Germany." [4]

Notes

- â George Steinmetz and Julia Hell (2006), The Visual Archive of Colonialism Public Culture, 18:1:147-184. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- â Henning Melber (2005), Genocide and the history of violent expansionism Pambazuka News, A Weekly Electronic Forum For Social Justice In Africa. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- â Friedrichsmeyer, et al. (1998), 4.

- â Friedrichsmeyer, et al. (1998), 6.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boahen, A. Adu (ed.). Africa Under Colonial Domination, 1880-1935, Abridged version. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0520067028

- Friedrichsmeyer, Sara, Sara Lennox, and Susanne Zantop. The imperialist imagination: German colonialism and its legacy. Social history, popular culture, and politics in Germany. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0472096824

- Smith, Woodruff D. "The Ideology of German Colonialism, 1840â1906." Journal of Modern History. 46 (1974):641â663

- Smith, Woodruff D. The German colonial empire. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0807813225

- Stoecker, Helmut (ed.) and Bemd Zöllner. German Imperialism in Africa: From the Beginnings Until the Second World War. Atlantic Highland, NJ: Humanities Press International, 1986. ISBN 978-0391033832

- Wesseling, H. L., and Arnold J. Pomerans (trans.). Divide and Rule: The Partition of Africa, 1880â1914. Westport, CT: Preager, 1996. ISBN 978-0275951375

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.