Abraham Ben Meir Ibn Ezra

Rabbi Abraham Ben Meir Ibn Ezra (also known as Ibn Ezra, or Abenezra) (1092 or 1093 ‚Äď 1167) was one of the most distinguished Jewish men of letters and writers of the Middle Ages. Ibn Ezra excelled in philosophy, astronomy and astrology, medicine, poetry, linguistics, and exegesis; he was called The Wise, The Great and The Admirable Doctor.

Born in Spain, he spent much of his life traveling in North Africa, the Middle East, England, Italy and France. More than one hundred of his works, written in Hebrew, made the scholarship of the Arab world accessible to the Jews of European Christendom. He wrote on biblical exegesis, philosophy, Hebrew grammar, medicine, astrology, astronomy, and mathematics. His Biblical exegesis focused on the use of grammatical principles and attention to literal meaning of biblical texts, and elaborated a Neoplatonic view of the cosmos. He is also known as an exceptional Hebrew poet. His translation of the works of the grammarian Judah Hayyuj laid the groundwork for the study of Hebrew grammar in Europe.

Life

Ibn Ezra was born at Tudela (currently province of Navarra), Spain in 1092 or 1093 C.E., when the town was under Muslim rule. Several members of his family appear to have held important posts in Andalusia. Ibn Ezra claimed to have little business ability. ‚ÄúIf I sold candles,‚ÄĚ he wrote, ‚Äúthe sun would never set; if I dealt in shrouds, men would become immortal.‚ÄĚ He apparently supported himself by teaching and writing poetry, and through the support of his patrons. Ibn Ezra was a friend of Judah Ha-Levi, and tradition holds that he married Judah‚Äôs daughter.

After the deaths of three of his children and the conversion of a son to Islam, Ibn Ezra became a wanderer and left Spain sometime before 1140. He remained a wanderer for the rest of his life, probably because of the persecution inflicted on the Jews in Spain. During the later part of his life he wrote over one hundred works in prose. He made journeys to North Africa, Egypt, Palestine, and Iraq. After the 1140s, he moved around Italy (Rome, Rodez, Lucca, Mantua, Verona), southern France (Narbonne, Béziers), northern France (Dreux), and England. From 1158 to 1160 he lived in London. He traveled back again to the south of France, and died on January 23 or 28, 1167, the exact location unknown.

Thought and Works

Ibn Ezra continues to be recognized as a great Hebrew poet and writer. His prose works, written in the Hebrew language, made accessible to the Jews of Christian Europe, the ideas which had been developed by scholars in the Arabic world. The versatility of his learning and his clear and charming Hebrew style made him especially qualified for this role. Discovering that the Jews of Italy did not understand Hebrew grammar, he wrote a book elucidating Hayyuj's tri-letter root theory. Yesod Mora ("Foundation of Awe"), on the division and the reasons for the Biblical commandments, he wrote in 1158 for a London friend, Joseph ben Jacob.

Ibn Ezra produced works on Biblical exegesis, religion, philosophy, grammar, medicine, astronomy, astrology, nutrition, mathematics and how to play the game of chess. His works were widely published throughout Europe, and some were later translated into Latin, Spanish, French, English and German. Ibn Ezra also introduced the decimal system to Jews living in the Christian world. He used the Hebrew digits alef to tet for 1‚Äď9, added a special sign to indicate zero, and then placed the tens to the left of the digits in the usual way. He also wrote on the calendar, the use of planetary tables, and the astrolabe.

Ibn Ezra’s poetry was written in Hebrew, borrowing from Arabic meter and style. He wrote on a wide variety of themes, both secular and religious.

Hebrew Grammar

Ibn Ezra’s grammatical writings, among which Moznayim ("Scales," 1140) and Zahot ("Correctness," 1141) are the most valuable, were the first expositions of Hebrew grammar in the Hebrew language, in which the system of Judah Hayyuj and his school prevailed. He also translated into Hebrew the two writings of Hayyuj in which the foundations of the system were laid down.

Biblical Exegesis

The originality of the exegesis of Ibn Ezra came from his concentration on grammatical principles and literal meaning to arrive at the simplest meaning of the text, the Peshat, although he took a great part of his exegetical material from his predecessors. He avoided the traditional assumption of medieval exegesis, that certain texts had hidden levels of meaning. Ibn Ezra belongs to the earliest pioneers of the higher biblical criticism of the Pentateuch.

Ibn Ezra‚Äôs philosophical ideas were presented in his biblical commentaries, couched in discreet language to avoid offending ultra-orthodox readers. His commentary on the first verse of Genesis demonstrates that the verb bara (to create) can also mean ‚Äúto shape‚ÄĚ or ‚Äúto divide,‚ÄĚ implying pre-existent matter. This is followed with a favorite phrase, ‚Äúlet him who can understand, do so,‚ÄĚ which Ibn Ezra used repeatedly to designate passages with philosophical significance.

Philosophy

Abraham Ibn Ezra’s thought was essentially Neoplatonic. He was influenced by Solomon Ibn Gabirol and included in his commentary excerpts from Gabirol’s allegorical interpretation of the account of the Garden of Eden. Like Gabirol, he said of God: "He is all, and all comes from Him; He is the source from which everything flows." Ibn Ezra described the process of the world's emanation from God using the Neoplatonic image of the emergence of many from the One, and compared it to the process of speech issuing from the mouth of a speaker.

Ibn Ezra suggested that the form and matter of the intelligible world emanated from God, and was eternal. The terrestrial world was formed of pre-existent matter through the mediation of the intelligible world. The biblical account of creation concerned only the terrestrial world. The universe consisted of three ‚Äúworlds‚ÄĚ: the "upper world" of intelligibles or angels; the "intermediate world" of the celestial spheres; and the lower, "sublunar world," which was created in time. His ideas on the creation were a powerful influence on later kabbalists.

Astrology

The division of the universe into spiritual, celestial and sublunary (terrestrial) worlds‚ÄĒwith the celestial world serving as an intermediary to transmit God‚Äôs will to Earth‚ÄĒgave astrology a significant role in medieval thought. Ibn Ezra believed that the planets exercised a direct influence on the physical body, and wrote a dozen short works on astrology. The Beginning of Wisdom, accompanied by a commentary, The Book of Reasons, summarized the foundations of astrology based on Arabic sources but including original material from Ibn Ezra. These works remained of interest to medieval scholars; some were translated into French during the thirteenth century, and all were later translated into Latin by Pietro d‚ÄôAlbaro.

Works

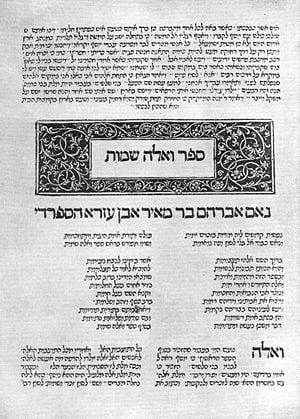

Ibn Ezra wrote commentaries on most of the books of the Bible, of which, however, the Books of Paralipomenon have been lost. His reputation as an intelligent and acute expounder of the Bible was founded on his commentary on the Pentateuch, on which numerous commentaries which were written. In the editions of this commentary, the commentary on the book of Exodus is replaced by a second, more complete commentary, while the first and shorter commentary on Exodus was not printed until 1840. The great editions of the Hebrew Bible with rabbinical commentaries contained also commentaries of Ibn Ezra's on the following books of the Bible: Isaiah, Minor Prophets, Psalms, Job, Pentateuch, Daniel; the commentaries on Proverbs, Ezra and Nehemiah which bear his name are really those of Moses Kimhi. Ibn Ezra wrote a second commentary on Genesis as he had done on Exodus, but this was never finished. There are second commentaries also by him on the Song of Songs, Esther and Daniel.

In his biblical commentary, Ibn Ezra adheres to the literal sense of the texts, avoiding Rabbinic allegories and Kabbalistic extravagances, though he remains faithful to the Jewish traditions. This does not prevent him from exercising an independent criticism, which, according to some writers, borders on rationalism. In contrast his other works, the most important of which include The Book of the Secrets of the Law, The Mystery of the Form of the Letters, The Enigma of the Quiescent Letters, The Book of the Name, The Book of the Balance of the Sacred Language and The Book of Purity of the Language, demonstrate a more Cabbalistic viewpoint.

Biblical Commentaries

Ibn Ezra’s chief work is the commentary on the Torah, which, like that of Rashi, has called forth a host of super-commentaries, and which has done more than any other work to establish his reputation. It is extant both in numerous manuscripts and in printed editions. The commentary on Exodus published in the printed editions is a work by itself, which he finished in 1153 in southern France.

The complete commentary on the Pentateuch, which, as has already been mentioned, was finished by Ibn Ezra shortly before his death, was called Sefer ha-Yashar ("Book of the Straight").

In the rabbinical editions of the Bible the following commentaries of Ibn Ezra on Biblical books are likewise printed: Isaiah; the Twelve Minor Prophets; Psalms; Job; the Megillot; Daniel. The commentaries on Proverbs and Ezra-Nehemiah which bear Ibn Ezra's name are by Moses Kimhi. Another commentary on Proverbs, published in 1881 by Driver and in 1884 by Horowitz, is also erroneously ascribed to Ibn Ezra. Additional commentaries by Ibn Ezra to the following books are extant: Song of Solomon; Esther; Daniel. He also probably wrote commentaries to a part of the remaining books, as may be concluded from his own references.

Hebrew Grammar

- Moznayim (1140), chiefly an explanation of the terms used in Hebrew grammar.

- Translation of the work of Hayyuj into Hebrew (ed. Onken, 1844)

- Sefer ha-Yesod or Yesod DiŠł≥duŠł≥, still unedited

- ZaŠł•ot (1145), on linguistic correctness, his best grammatical work, which also contains a brief outline of modern Hebrew meter; first ed. 1546

- Safah Berurah (first ed. 1830)

- A short outline of grammar at the beginning of the unfinished commentary on Genesis

Smaller Works, Partly Grammatical, Partly Exegetical

- Sefat Yeter, in defense of Saadia Gaon against Dunash ben LabraŠĻ≠, whose criticism of Saadia, Ibn Ezra had brought with him from Egypt (published by Bislichs, 1838 and Lippmann, 1843)

- Sefer ha-Shem (ed. Lippmann, 1834)

- Yesod Mispar, a small monograph on numerals (ed. Pinsker, 1863)

- Iggeret Shabbat, a responsum on the Sabbath dated 1158 (ed. Luzzatto in Kerem Šł§emed)

Religious Philosophy

Yesod Mora Vesod Hatorah (1158), on the division of and reasons for the Biblical commandments; 1st ed. 1529.

Mathematics, Astronomy, Astrology

- Sefer ha-EŠł•ad, on the peculiarities of the numbers 1-9.

- Sefer ha-Mispar or Yesod Mispar, arithmetic.

- Luhot, astronomical tables.

- Sefer ha-'Ibbur, on the calendar (ed. Halberstam, 1874).

- Keli ha-NeŠł•oshet, on the astrolabe (ed. Edelmann, 1845).

- Shalosh She'elot, answer to three chronological questions of David Narboni.

- Translation of two works by the astrologer Mashallah: She'elot and Šł≤adrut

- Sefer Ha'te'amim (The Book of Reasons), an overview of Arabic astrology (tr. M. Epstein, 1994)

- Reshith Hochma (The Beginning of Wisdom), an introduction to astrology (tr. M. Epstein, 1998)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary Sources

- Ibn Ezra, Abraham ben Meir. Sefer Hanisyonot: The Book of Medical Experiences Attributed to Abraham Ibn Ezra. The Magness Press, The Hebrew University, 1984.

- Ibn Ezra, Abraham ben Meir and Michael Friedlander. Commentary of Ibn Ezra on Isaiah. Feldheim Pub, 1966.

- Ibn Ezra, Abraham ben Meir and Michael Linetsky. Rabbi. Abraham Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Creation. Jason Aronson, 1998.

- Ibn Ezra, Abraham and Jay F. Shachter (trans.). Ibn Ezra on Leviticus: The Straightforward Meaning (The Commentary of Abraham Ibn Ezra on the Pentateuch, Vol. 3). Ktav Publishing House, 1986.

Secondary Sources

This article incorporates text from the 1901‚Äď1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

- Lancaster, Irene. Deconstructing the Bible: Abraham Ibn Ezra's Introduction to the Torah. Routledge Curzon, 2002.

- Twersky, Isadore and Jay M. Harris (eds.). Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra: Studies in the Writings of a Twelfth-Century Jewish Polymath (Harvard Judaic Texts and Studies). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994.

- Wacks, David. ‚ÄúThe Poet, the Rabbi, and the Song: Abraham ibn Ezra and the Song of Songs.‚ÄĚ Wine, Women, and Song: Hebrew and Arabic Literature in Medieval Iberia. Edited by Michelle M. Hamilton, Sarah J. Portnoy and David A. Wacks. Newark, DE: Juan de la Cuesta Hispanic Monographs, 2004. pp. 47-58.

External Links

All links retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ‚ÄúRabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra‚ÄĚ - An article by Meira Epstein, detailing all of Ibn Ezra's extant astrological works

- Skyscript: The Life and Work of Abraham Ibn Ezra

- Abraham Ibn Ezra

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.