Difference between revisions of "Wat Phou" - New World Encyclopedia

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (43 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{approved}}{{submitted}}{{ready}}{{images OK}}{{copyedited}} | ||

{{Infobox World Heritage Site | {{Infobox World Heritage Site | ||

|WHS = Vat Phou and Associated Ancient Settlements within the Champasak Cultural Landscape | |WHS = Vat Phou and Associated Ancient Settlements within the Champasak Cultural Landscape | ||

| Line 12: | Line 13: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Wat Phou''' (Vat Phu) is a | + | '''Wat Phou''' (Vat Phu) is a [[Khmer people|Khmer]] ruined temple complex in southern [[Laos]] located at the base of Mount [[Phu Kao]], {{convert|6|km}} from the [[Mekong river]] in [[Champasak Province|Champassak]] province. Previously named Shrestapura, the city had been the capital of the Chenla and Champa kingdoms. The Mekong river, which had been viewed as symbolic of the Ganges River in India, became the host site for the first Hindu temples during those dynasties. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | A Hindu [[temple]] dedicated to [[Shiva]] stood on the site as early as the fifth century C.E., but the surviving structures date from the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. In the eleventh century, during the [[Koh Ker]] and [[Baphuon]] eras, the [[Hindu architecture|temples]] had been rebuilt using the original stones. The [[Hindu temples|temple]] has a unique design, the devotee moving through the entrance to a [[shrine]] where a [[linga]] was bathed in [[sacred water]] from a mountain [[spring (hydrosphere)|spring]]. During the thirteenth century, Wat Phou became a center of [[Theravada Buddhism|Theravada Buddhist]] worship, which it remains today. [[UNESCO]] designated Wat Phou a [[World Heritage Site]] in 2001 as '''Vat Phou and Associated Ancient Settlements within the Champasak Cultural Landscape.''' | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | + | [[Shrestapura]], which laid on the bank of the [[Mekong]] directly east of [[Mount Lingaparvata]], had been the original name of the town (now called [[Phu Kao]]) that hosts Wat Phou.<ref>Projet de Recherches en Archaeologie Lao, ''Vat Phu: The Ancient City, The Sanctuary, The Spring'' (pamphlet).</ref>Records and inscriptions indicate that, by the latter part of the fifth century, Shrestapura served as the capital of the [[Chenla]] and [[Champa]] [[monarchy|kingdoms]]. The first temples had been constructed on Mount Lingaparvata during that period.<ref>Freeman, ''A Guide to Khmer Temples in Thailand and Laos,'' 200-201.</ref> Hindu craftsmen adorned Mount Lingaparvata's summit with a [[linga]]-shaped stupa in reverence of [[Shiva]] whom they believe made his home there.<ref>Nations Online, [http://www.nationsonline.org/album/Laos/slides/Vat-Phou_28.htm Main entrance to Vat Phou Temple complex.] Retrieved January 21, 2009.</ref> The Mekong river represented the ocean or the [[Ganges River]].<ref>UNESCO, [http://whc.unesco.org/archive/advisory_body_evaluation/481.pdf Advisor Body Evaluation.] Retrieved January 21, 2009.</ref> The temples, also dedicated to Shiva, boast sacred springs near by. | |

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | Wat Phou | + | During the reign of [[Yashovarman I]] in the early tenth century, Wat Phou fell within the boundaries of the [[Khmer empire]], with its capital in [[Angkor]].<ref>Hindu Wisdom, [http://www.hinduwisdom.info/Glimpses_XVIII.htm A Glorious Hindu Legacy: Indic influence in Southeast Asia.] Retrieved January 9, 2009.</ref> The ancient town of [[Shrestapura]] had been replaced by a town whose name had been unrecorded, the predecessor of [[Phu Kao]] in the Angkorian period.<ref>UNESCO, [http://whc.unesco.org/archive/advisory_body_evaluation/481.pdf UNESCO Advisor Body Evaluation.] Retrieved January 21, 2009.</ref> |

| + | [[Image:Laos Champasak.png|thumb|right|220px|Map of Laos highlighting the Champassak province, the location of Wat Phou]] | ||

| + | In the eleventh century, during the [[Koh Ker]] and [[Baphuon]] periods, the temples had been reconstructed using many of the stone blocks from the original temples. Minor renovations had been made between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries. In the thirteenth century, Wat Phou, like most in the empire, converted to [[Theravada Buddhism]]. The [[Lao people|Lao]] continued Wat Phou as a Theravada Buddhist after they took control of the region. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A festival is held on the site each February. Little restoration work has been done during twentieth and twenty first centuries, with the exception of boundary posts along the paths. | ||

==The site== | ==The site== | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | {{wide image|Watphouplan01.png|600px|<center><big>'''Lay out of Wat Phou'''</big></center>}} |

| − | Like most Khmer temples, Wat Phou | + | |

| + | [[Image:Watphoupeaklinga03.jpg|right|thumb|180px|The mountain has a natural [[linga]] on its peak.]] | ||

| + | Like most Khmer temples, Wat Phou orientates towards the east. The axis actually faces eight degrees south of due east, determined by adjusting to the the positions of the mountain and the river. Including the [[Architecture of Cambodia#Srahs and barays|barays]], it stretches {{convert|1.4|km}} east from the source of the spring at the base of a cliff {{convert|100|m}} up the hill. The city lays {{convert|6|km}} east of the temple, on the west bank of the Mekong, with other temples and the city of Angkor to the south.<ref>Lawrence Palmer Briggs, "The ancient Khmer Empire," ''Transactions of the American Philosophical Society'' (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1951), 161.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Approached from the city (of which little remains), the first part of the temple consists of a number of [[barays]]. Only one contains water, the {{convert|600|by|200|m|1}}middle baray laying directly along the axis of the temples. Reservoirs similar in construction and layout sit north and south of that one, along with another pair on each side of the causeway between the middle baray and the palaces. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The two palaces stand on a terrace on either side of the axis, known as the "north and south" palaces or the "men's and women's" palaces. The reason they have been designated men's and women's or palaces remains unknown as they had been neither palaces nor used designated by gender. Each palace consisted of a rectangular courtyard with a corridor and entrance on the sides and false doors at the east and west ends. The courtyards of both buildings have [[laterite]] walls; the walls of the northern palace's corridor are also laterite, while those of the southern palace are [[sandstone]]. The northern building is in better condition than the southern building. The palaces have been noted primarily for their pediments and lintels, crafted in the early [[Angkor Wat]] style.<ref>Brajendra Kumar, ''Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia'' (New Delhi: Akansha Publishing House, 2006), 214.</ref> | ||

| + | The next terrace has a small shrine to [[Nandin]] ([[Shiva]]'s mount) to the south, in need of restoration. The road connecting Wat Phou to [[Angkor]] ran south from this temple. Continuing west, successive staircases lead up further terraces; between them stands a dvarapala which, during recent times, has been worshipped as king [[Kammatha]], mythical builder of the temple. The remains of six small shrines destroyed by treasure-hunters litter the narrow, next terrace. | ||

[[Image:Wpfacade02a.jpg|thumb|right|220px|The facade of the sanctuary. The Buddha image inside is modern.]] | [[Image:Wpfacade02a.jpg|thumb|right|220px|The facade of the sanctuary. The Buddha image inside is modern.]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The path ends with seven sandstone tiers rising to the upper terrace and central sanctuary. The sanctuary has two parts,<ref>Kumar, ''Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia,'' 214.</ref> with the front section constructed with sandstone boasting four [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]] images. The brick rear part stands empty with the central [[linga]] missing. A makeshift covering has been added to the front to replace the collapsed roof. |

| − | The | + | Water from the spring, emerging from the cliff about {{convert|60|m}} southwest of the sanctuary, channeled along stone aqueducts into the rear chamber, continuously bathing the linga. The sanctuary had been constructed at a later date than the north and south palaces, belonging to the [[Baphuon]] period of the later eleventh century. The east side has three doorways: from south to north, their pediments show [[Krishna]] defeating the [[naga (mythology)|naga]] Kaliya; [[Indra]] riding [[Airavata]]; and [[Vishnu]] riding [[Garuda]]. The east wall displays carvings of [[dvarapala]]s and [[devata]]s. Entrances to the south and north have inner and outer [[lintel]]s, including one to the south of Krishna ripping [[Kamsa]] apart. |

| − | [[ | + | Other features of the area include a [[library]], south of the sanctuary, in need of restoration, and a relief of the [[Hindu trinity]] to the northwest.<ref>Kumar, ''Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia,'' 215.</ref> Carvings further north include a [[Buddha's footprint]] on the cliff-face, and boulders shaped to resemble elephants and a crocodile. Local lore presents the crocodile stone as the site of an annual [[human sacrifice]] described in a sixth century Chinese text. The identification has been considered plausible since the crocodile's dimensions are comparable to a human being. |

| − | + | ==Gallery== | |

| − | + | <center> | |

| + | <gallery> | ||

| + | Image:Wpkrishnakillinguncle01.jpg|A lintel showing Krishna killing Kamsa, on the south wall of the sanctuary | ||

| + | Image:Wpvishnuongaruda01.jpg|A [[lintel (architecture)|lintel]] showing Vishnu on Garuda, on the north-east wall of the sanctuary | ||

| + | Image:Wat Phou South side.jpg|Wat Phou(Southern Palace) | ||

| + | Image:Vat Phu.jpg|Wat Phu, Laos | ||

| + | Image:Indra riding Airavata.jpg|Indra riding Airavata, Wat Phou | ||

| + | Image:Hindu trinity - Wat Phou.jpg|Hindu trinity, Wat Phou | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | </center> | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| Line 48: | Line 70: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Briggs, Lawrence Palmer. 1951. ''The Ancient Khmer Empire. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society.'' Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. OCLC 527144. | |

| − | * Briggs, Lawrence Palmer. 1951. The | + | * Freeman, Michael. 1998. ''A Guide to Khmer Temples in Thailand & Laos''. New York: Weatherhill. ISBN 9780834804500. |

| − | * Freeman, Michael. 1998. ''A | + | * Higham, Charles. 2001. ''The Civilization of Angkor''. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520234420. |

| − | * Higham, Charles. 2001. ''The | + | * Kumar, Brajendra. 2006. ''Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia. New Delhi: Akansha Publishing House. ISBN 9788183700733. |

| − | * Kumar, Brajendra. 2006. Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia. New Delhi: Akansha Publishing House. ISBN 9788183700733. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* Parmentier, Henri. 1914. "Le temple de Vat Phu. Vat Nokor. L'architecture interprétée dans les monuments du Cambodge. L'art d'Indravarman. Complément à l'art khmèr primitif. La construction dans l'architecture khèmere classique." ''Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient''. Hanoi: Imprimerie d'Extrême-Orient. OCLC 236233048. | * Parmentier, Henri. 1914. "Le temple de Vat Phu. Vat Nokor. L'architecture interprétée dans les monuments du Cambodge. L'art d'Indravarman. Complément à l'art khmèr primitif. La construction dans l'architecture khèmere classique." ''Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient''. Hanoi: Imprimerie d'Extrême-Orient. OCLC 236233048. | ||

* Projet de Recherches en Archaeologie Lao. ''Vat Phu: The Ancient City, The Sanctuary, The Spring'' (pamphlet). | * Projet de Recherches en Archaeologie Lao. ''Vat Phu: The Ancient City, The Sanctuary, The Spring'' (pamphlet). | ||

| − | * Santoni, M. ''et al.'' | + | * Santoni, M., ''et al.'' "Excavations at Champasak and Wat Phu (Southern Laos), in European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists." Roberto Ciarla, Fiorella Rispoli, and Oscar Nalesini. 1998. South-East Asian archaeology, 1992: proceedings of the ''Fourth International Conference of the European Association of South-East Asian Archaeologists.'' Rome, 28th September-4th October 1992. Serie orientale Roma, v. 77. Roma: Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente. OCLC 39340733. |

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved May 3, 2023. | |

| + | |||

* [http://whc.unesco.org/archive/advisory_body_evaluation/481.pdf Report on World Heritage Site application] | * [http://whc.unesco.org/archive/advisory_body_evaluation/481.pdf Report on World Heritage Site application] | ||

| − | + | * [http://www.hinduwisdom.info/Glimpses_XVIII.htm A Glorious Hindu Legacy: Indic influence in Southeast Asia.] | |

{{Angkorian sites}} | {{Angkorian sites}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Geography]] | [[Category:Geography]] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:14, 3 May 2023

| Vat Phou and Associated Ancient Settlements within the Champasak Cultural Landscape* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 481 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

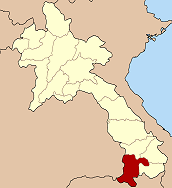

Wat Phou (Vat Phu) is a Khmer ruined temple complex in southern Laos located at the base of Mount Phu Kao, 6 kilometers (3.7 mi) from the Mekong river in Champassak province. Previously named Shrestapura, the city had been the capital of the Chenla and Champa kingdoms. The Mekong river, which had been viewed as symbolic of the Ganges River in India, became the host site for the first Hindu temples during those dynasties.

A Hindu temple dedicated to Shiva stood on the site as early as the fifth century C.E., but the surviving structures date from the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. In the eleventh century, during the Koh Ker and Baphuon eras, the temples had been rebuilt using the original stones. The temple has a unique design, the devotee moving through the entrance to a shrine where a linga was bathed in sacred water from a mountain spring. During the thirteenth century, Wat Phou became a center of Theravada Buddhist worship, which it remains today. UNESCO designated Wat Phou a World Heritage Site in 2001 as Vat Phou and Associated Ancient Settlements within the Champasak Cultural Landscape.

History

Shrestapura, which laid on the bank of the Mekong directly east of Mount Lingaparvata, had been the original name of the town (now called Phu Kao) that hosts Wat Phou.[1]Records and inscriptions indicate that, by the latter part of the fifth century, Shrestapura served as the capital of the Chenla and Champa kingdoms. The first temples had been constructed on Mount Lingaparvata during that period.[2] Hindu craftsmen adorned Mount Lingaparvata's summit with a linga-shaped stupa in reverence of Shiva whom they believe made his home there.[3] The Mekong river represented the ocean or the Ganges River.[4] The temples, also dedicated to Shiva, boast sacred springs near by.

During the reign of Yashovarman I in the early tenth century, Wat Phou fell within the boundaries of the Khmer empire, with its capital in Angkor.[5] The ancient town of Shrestapura had been replaced by a town whose name had been unrecorded, the predecessor of Phu Kao in the Angkorian period.[6]

In the eleventh century, during the Koh Ker and Baphuon periods, the temples had been reconstructed using many of the stone blocks from the original temples. Minor renovations had been made between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries. In the thirteenth century, Wat Phou, like most in the empire, converted to Theravada Buddhism. The Lao continued Wat Phou as a Theravada Buddhist after they took control of the region.

A festival is held on the site each February. Little restoration work has been done during twentieth and twenty first centuries, with the exception of boundary posts along the paths.

The site

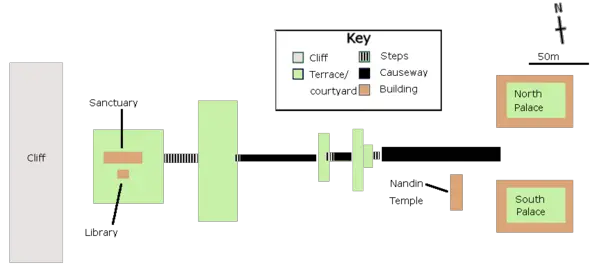

Like most Khmer temples, Wat Phou orientates towards the east. The axis actually faces eight degrees south of due east, determined by adjusting to the the positions of the mountain and the river. Including the barays, it stretches 1.4 kilometers (0.87 mi) east from the source of the spring at the base of a cliff 100 meters (330 ft) up the hill. The city lays 6 kilometers (3.7 mi) east of the temple, on the west bank of the Mekong, with other temples and the city of Angkor to the south.[7]

Approached from the city (of which little remains), the first part of the temple consists of a number of barays. Only one contains water, the 600 by 200 meters (1,968.5 ft × 656.2 ft) middle baray laying directly along the axis of the temples. Reservoirs similar in construction and layout sit north and south of that one, along with another pair on each side of the causeway between the middle baray and the palaces.

The two palaces stand on a terrace on either side of the axis, known as the "north and south" palaces or the "men's and women's" palaces. The reason they have been designated men's and women's or palaces remains unknown as they had been neither palaces nor used designated by gender. Each palace consisted of a rectangular courtyard with a corridor and entrance on the sides and false doors at the east and west ends. The courtyards of both buildings have laterite walls; the walls of the northern palace's corridor are also laterite, while those of the southern palace are sandstone. The northern building is in better condition than the southern building. The palaces have been noted primarily for their pediments and lintels, crafted in the early Angkor Wat style.[8]

The next terrace has a small shrine to Nandin (Shiva's mount) to the south, in need of restoration. The road connecting Wat Phou to Angkor ran south from this temple. Continuing west, successive staircases lead up further terraces; between them stands a dvarapala which, during recent times, has been worshipped as king Kammatha, mythical builder of the temple. The remains of six small shrines destroyed by treasure-hunters litter the narrow, next terrace.

The path ends with seven sandstone tiers rising to the upper terrace and central sanctuary. The sanctuary has two parts,[9] with the front section constructed with sandstone boasting four Buddha images. The brick rear part stands empty with the central linga missing. A makeshift covering has been added to the front to replace the collapsed roof.

Water from the spring, emerging from the cliff about 60 meters (200 ft) southwest of the sanctuary, channeled along stone aqueducts into the rear chamber, continuously bathing the linga. The sanctuary had been constructed at a later date than the north and south palaces, belonging to the Baphuon period of the later eleventh century. The east side has three doorways: from south to north, their pediments show Krishna defeating the naga Kaliya; Indra riding Airavata; and Vishnu riding Garuda. The east wall displays carvings of dvarapalas and devatas. Entrances to the south and north have inner and outer lintels, including one to the south of Krishna ripping Kamsa apart.

Other features of the area include a library, south of the sanctuary, in need of restoration, and a relief of the Hindu trinity to the northwest.[10] Carvings further north include a Buddha's footprint on the cliff-face, and boulders shaped to resemble elephants and a crocodile. Local lore presents the crocodile stone as the site of an annual human sacrifice described in a sixth century Chinese text. The identification has been considered plausible since the crocodile's dimensions are comparable to a human being.

Gallery

See Also

Notes

- ↑ Projet de Recherches en Archaeologie Lao, Vat Phu: The Ancient City, The Sanctuary, The Spring (pamphlet).

- ↑ Freeman, A Guide to Khmer Temples in Thailand and Laos, 200-201.

- ↑ Nations Online, Main entrance to Vat Phou Temple complex. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ↑ UNESCO, Advisor Body Evaluation. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ↑ Hindu Wisdom, A Glorious Hindu Legacy: Indic influence in Southeast Asia. Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- ↑ UNESCO, UNESCO Advisor Body Evaluation. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ↑ Lawrence Palmer Briggs, "The ancient Khmer Empire," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1951), 161.

- ↑ Brajendra Kumar, Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia (New Delhi: Akansha Publishing House, 2006), 214.

- ↑ Kumar, Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia, 214.

- ↑ Kumar, Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia, 215.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Briggs, Lawrence Palmer. 1951. The Ancient Khmer Empire. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. OCLC 527144.

- Freeman, Michael. 1998. A Guide to Khmer Temples in Thailand & Laos. New York: Weatherhill. ISBN 9780834804500.

- Higham, Charles. 2001. The Civilization of Angkor. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520234420.

- Kumar, Brajendra. 2006. Encyclopaedia of Southeast Asia. New Delhi: Akansha Publishing House. ISBN 9788183700733.

- Parmentier, Henri. 1914. "Le temple de Vat Phu. Vat Nokor. L'architecture interprétée dans les monuments du Cambodge. L'art d'Indravarman. Complément à l'art khmèr primitif. La construction dans l'architecture khèmere classique." Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. Hanoi: Imprimerie d'Extrême-Orient. OCLC 236233048.

- Projet de Recherches en Archaeologie Lao. Vat Phu: The Ancient City, The Sanctuary, The Spring (pamphlet).

- Santoni, M., et al. "Excavations at Champasak and Wat Phu (Southern Laos), in European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists." Roberto Ciarla, Fiorella Rispoli, and Oscar Nalesini. 1998. South-East Asian archaeology, 1992: proceedings of the Fourth International Conference of the European Association of South-East Asian Archaeologists. Rome, 28th September-4th October 1992. Serie orientale Roma, v. 77. Roma: Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente. OCLC 39340733.

External Links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Report on World Heritage Site application

- A Glorious Hindu Legacy: Indic influence in Southeast Asia.

| ||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.