Difference between revisions of "Thomas Hobbes" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Johnston | + | *David Johnston; Thomas Hobbes. ''The Rhetoric of Leviathan''. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986. ISBN 0691077177 ISBN 9780691077178 |

| − | * Macpherson, C. B. | + | * Macpherson, C. B. ''The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke''. Oxford, New York, Oxford University Press, 1967. ISBN 0198810849 ISBN 9780198810841 |

| − | * Mintz, S. | + | *Mintz, S. ''The Hunting of Leviathan''. Cambridge [Eng.] University Press, 1962. |

| − | * Peters, R. | + | *Peters, R. ''Hobbes''. Harmondsworth, Middlesex; Penguin Books, 1956. |

| − | * Skinner, Q. | + | *Skinner, Q. ''Reason and Rhetoric in the Philosophy of Hobbes''. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521554365 ISBN 9780521554367 |

| − | * Sommerville | + | * J P Sommerville. ''Thomas Hobbes: Political Ideas in Historical Context''. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. ISBN 0312079664 ISBN 9780312079666 |

| − | * Sorell, T. | + | *Sorell, T. ''Hobbes''. London; New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986. ISBN 0710098456 ISBN 9780710098450 |

| − | * Sorell, T. | + | *Sorell, T. ''The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521410193 ISBN 9780521410199 |

| − | * Sorell, Tom | + | *Sorell, Tom. ''Hobbes, Thomas''. In E. Craig (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge, 2007 |

| − | * Tuck, R. | + | * Tuck, R. ''Hobbes''. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0192876686 ISBN 9780192876683 |

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

Revision as of 22:04, 10 July 2007

| Western Philosophers 17th-century philosophy (Modern Philosophy) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name: Thomas Hobbes | |

| Birth: April 5, 1588 Malmesbury, Wiltshire, England | |

| Death: December 4, 1679 Derbyshire, England | |

| School/tradition: Social contract, realism | |

| Main interests | |

| Political philosophy, history, ethics, geometry | |

| Notable ideas | |

| modern founder of the social contract tradition; life in the state of nature is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short" | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Plato, Aristotle | All subsequent Western political philosophy |

- "Hobbes" redirects here. For other people called Hobbes, see Hobbes (disambiguation).

Thomas Hobbes (April 5, 1588–December 4, 1679) was an English philosopher, whose famous 1651 book Leviathan set the agenda for a huge portion of subsequent Western political philosophy. Although Hobbes is today best remembered for his work on political philosophy, he contributed to a diverse array of fields, including history, geometry, ethics, general philosophy and what would now be called political science. Additionally, Hobbes's account of human nature as self-interested cooperation has proved to be an enduring theory in the field of philosophical anthropology.

Life

Early life and education

Hobbes was born in Westport, Wiltshire, England on April 5, 1588. His father, the vicar of Westport, was forced to leave the town, abandoning his three children to the care of an older brother Francis. Hobbes was educated at Westport church from the age of four, passed to the town's public school and then to a private school kept by a young man named Robert Latimer, a graduate from Oxford University. Hobbes was a good pupil, and around 1603 he was sent to Oxford and entered at Magdalen Hall.

At university, Hobbes appears to have followed his own curriculum; he was "little attracted by the scholastic learning." He did not complete his degree until 1608, but he was recommended by Sir James Hussee, his master at Magdalen, as tutor to William, the son of William Cavendish, Baron of Hardwick (and later Earl of Devonshire), and began a lifelong connection with that family.

Hobbes became a companion to the younger William and they both took part in a grand tour of continental Europe in 1610. Hobbes was exposed to European scientific and critical methods during the tour in contrast to the scholastic philosophy which he had learned in Oxford. His scholarly efforts at the time were aimed at a careful study of classic Greek and Latin authors, the outcome of which was, in 1628, his great translation of Thucydides's History of the Peloponnesian War into English. Hobbes believed that Thucydides's account of the Peloponnesian War showed that democratic government could not survive war or provide stability and was thus undesirable.

Although he associated with literary figures like Ben Jonson and thinkers such as Francis Bacon, Hobbes did not extend his efforts into philosophy until after 1629. His employer Cavendish, then the Earl of Devonshire, died of the plague in June 1628. The widowed countess dismissed Hobbes but he soon found work nearby, again a tutor, this time to the son of Sir Gervase Clifton. Hobbes again toured Europe as part of his employment, this time becoming familiar with Euclid's work.

In 1631 he again found work with the Cavendish family, tutoring the son of his previous pupil. Over the next seven years he expanded his own knowledge of philosophy, awakening in him curiosity over key philosophic debates. He visited Florence in 1636 and later was a regular debater in philosophic groups in Paris, held together by Marin Mersenne.

In Paris

Hobbes came home, in 1637, to a country riven with discontent, which disrupted him from the orderly execution of his philosophic plan. In this environment, Hobbes developed a set of arguments in support of the royalist position, which, while not originally intended for publication, reached the general public in 1640 under the title The Elements of Law.

In November of 1640, Hobbes began to worry seriously about the reprecusions of his treatise and fled to Paris. There, he rejoined the coterie about Mersenne, and was invited by Mersenne to produce one of the sets of Objections that, along with a set of Replies, accompanied the original 1641 publication of René Descartes' landmark Meditations on First Philosophy.

Hobbes' first area of serious study concerned the physical doctrine of motion. By the mid-1640's, he had conceived a system of thought the elaboration of which he would devote his life to. His scheme was first to work out, in a separate treatise, a systematic doctrine of body, showing how physical phenomena were universally explicable in terms of motion. He would then single out man from the realm of nature, and show what specific bodily motions were involved in the production of the peculiar phenomena of sensation, knowledge, affections and passions, particularly those relevant to human interaction. Finally, he would consider how men were moved to enter into society, and argue how this must be regulated if Men were not to fall back into "brutishness and misery." Thus he proposed to unite the separate phenomena of body, man and the state.

It was the third part of the system that Hobbes first wrote and published (in 1641), entitled De Cive. Although it was initially only circulated privately, it was well received. Over the next few years, he published a work in metaphysics (Thomas White's De Mundo Examined, 1643) and a work in optics (A Minute or First Draught of the Optiques, in 1646).

Civil war in England

The English Civil War broke out in 1642, and when the Royalist cause began to decline from the middle of 1644 there was an exodus of the king's supporters to Europe. Many came to Paris and were known to Hobbes. This revitalised Hobbes's political interests, and the De Cive was republished and more widely distributed.

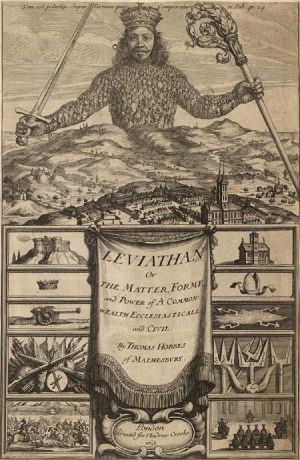

The company of the exiled royalists encouraged Hobbes to further develop his views on political theory. The state, it now seemed to Hobbes, might be regarded as a great artificial man or monster (Leviathan), composed of men, with a life that might be traced from its generation under pressure of human needs to its dissolution through civil strife proceeding from human passions. The work was closed with a general "Review and Conclusion," in direct response to the war which raised the question of the subject's right to change allegiance when a former sovereign's power to protect was irrecoverably gone.

During the years of the composition of Leviathan, Hobbes remained in or near Paris. In 1647 he was overtaken by a serious illness which disabled him for six months. On recovering from this near fatal disorder, he resumed his literary task, and carried it steadily forward to completion by the year 1650. In 1650, to prepare the way for his magnum opus, he allowed the publication of his earliest treatise, divided into two separate small volumes (Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie, and De corpore politico, or the Elements of Law, Moral and Politick). In 1651 he published his translation of the De Cive under the title of Philosophical Rudiments concerning Government and Society. Meanwhile the printing of the greater work was proceeding, and finally it appeared about the middle of 1651, under the title of Leviathan, or the Matter, Form and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiastical and Civil, with a famous title-page engraving in which, from behind hills overlooking a landscape, there towers the body of a crowned giant, made up of tiny figures of human beings and bearing sword and crozier in the two hands. The book was met with anger by the Paris Royalists, and Hobbes returned to London that same year.

Later life

The mid-1650's saw Hobbes completing the first two parts of his tripartite system. De Corpore, his work on physics, was published in 1655. The mathematics-based sections came under heavy (politically-motivated) attack, and Hobbes devoted a great deal of energy over the years that followed to defending the work. The middle part of the system, De homine was published in 1658. It received relatively little attention, and is today seen as of secondary importance.

In 1666, the House of Commons introduced a bill against atheism and profaneness. On October 17 of that year, it was ordered that the committee to which the bill was referred "should be empowered to receive information touching such books as tend to atheism, blasphemy and profaneness... in particular... the book of Mr. Hobbes called the Leviathan." (House of Commons Journal Volume 8. British History Online. Retrieved January 14, 2005.) Hobbes was terrified at the prospect of being labelled a heretic, and proceeded to address to issue in writing (first in an edition of his works published in Holland).

The only consequence that came of the bill was that Hobbes could never thereafter publish anything in England on subjects relating to human conduct. Other writings were not made public until after his death, including Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England and of the Counsels and Artifices by which they were carried on from the year 1640 to the year 1662.

In October 1679, Hobbes suffered a bladder disorder, which was followed by a paralytic stroke from which he died in his ninety-second year. He was buried in the churchyard of Ault Hucknall in Derbyshire, England.

Philosophy

Like his contemporary Descartes, Hobbes' philosophy is marked by a cautious optimism about our ability to overcome the limitations of our finite intellects and achieve knowledge of all aspects of the world we encounter. Like Spinoza, Hobbes was greatly impressed with the rigor of Euclid's Geometry, and believed that a similar level of rigor was possible with respect to physics, psychology, ethics and political philosophy. In contrast to the rationalists, however, Hobbes insisted on certain limitations of our knowledge in a way that foreshadowed John Locke's philosophical stance.

It is no coincidence that Hobbes is most often thought of today as a political philosopher, for he believed that political inquiries were both more important and capable of more certainty than inquiries concering entities not created by humans, and he focused his intellectual efforts accordingly.

Logic and Basic Concepts

Hobbes accepted the Aristotelian logic of the day, seeing it as the system of the proper rules for thought (a view which stands in contrast to the more mathematical way many contemporary logicians understand their discipline). The importance of logic in philosophy, for Hobbes, is not that it leads to any substantive truths on its own, but rather that it works to establish the proper level of rigor for philosophical enquiry.

In his Meditations, Descartes had claimed that some of our ideas were provided by the 'light of reason', and could not be derived from the senses. Among these ideas, he included all mathematical ideas (including that of space) and the idea of God. Hobbes rejected this approach, deriving all ideas from the senses in ways that would become standard fare for later British Empiricists. For instance, the idea of space is derived from mental images that present things to us as though they were distinct from us, and the idea of existence is derived from the thought of empty space being filled. His view that such apparently basic concepts were so derived made Hobbes suspicious of rationalist attempts to derive substantive truths from those ideas alone.

Psychology

Hobbes believed that humans were nothing more than matter, making him one of the most prominent materialists of the 17th century. Because of this, he believed that it was possible to explain human psychological operations in terms of the physical happenings of their bodies. For Hobbes, the central concept in physics is motion, so sensation is explained in terms of the communication of motion from external bodies to the sense organs. Thought is explained in terms of motions in the brain, and passions in terms of motions that the brain communicates to the heart.

Certain motions within a body are essential to its remaining alive, and these are primarily regulated by the heart. Hobbes used the idea of such essential motions to explain the basic human drives. Things which, through their influence on our sense organs, promote the essential motions are objects of pleasure, and we naturally pursue them. On the other side, things which counteract the essential motions are objects of pain, and we naturally avoid them.

Like Spinoza, Hobbes then derived the notions of 'good' and 'bad' from those of the pleasurable and the painful. As a result, he saw 'good' and 'bad' as inherently relative notions. On this view, nothing in the world can be said to be intrinsically good or bad; it is at most good or bad for certain beings. Because of this connection between the notions, humans naturally take sensations of pleasure as a guide to the good, but this can be misleading, for sensations of pleasure often lead us to ignore greater pleasures that can be had later at the cost of present pains. Because of this, philosophy has an important role to play in promoting human happiness, for logic-guided thinking is our best tool for discovering how to achieve the best life overall.

Political Thought

One of Hobbes' fundamental assumptions is that, if people were to pursue their natural inclinations, the result would be a war of all against all. Because of our fragility and finitude, we are always at risk of death, and so naturally attempt to acquire as much power over others as possible in order to ensure our safety. When such ends are pursued without restraint, the result is a state of war that is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short."

It is worth noting that Hobbes' view contains both a descriptive and a normative element. In other words, Hobbes is not only describing how it is that humans would operate in a pre-civilized 'state of nature,' but he is also discussing whether in such a situation they would be morally justified in acting as they do. Given his derivation of the concepts of good and evil from the pleasure and pain of individuals, and his theory of the pleasure and pain of individuals in terms of those motions that are essential for their survival, Hobbes has provided a systematic basis for the claim that ruthless self-preservation can (and, if no better means of survival are available, is) morally justified in the only sense we can give that phrase.

The state of nature is one in which the vast majority of individuals will fare quite badly, and for this reason, Hobbes believes, they naturally and justifiably form a commonwealth, ruled by a sovereign. In a commonwealth, the individuals submit themselves to the will of the sovereign, which allows contraints to be put on their actions that simply did not exist in the state of nature. For instance, in exchange for giving up the right to kill his enemies, a member of the commonwealth receives the sovereign's assurance that others (whether members of the commonwealth or not) will not be able to kill him without facing the punishment of the state. He therefore passes up certain advantages that murder could potentially bring him in exchange for the assurrance that others will have strong incentive not to murder him.

According to this view, the sovereign is justified in remaining in power and acting so long as his actions make the state of the commonwealth better than a state of nature. This consequence of Hobbes' theory strikes many as objectionable, for it allows, for instance, the sovereign to acquire extensive power over the individuals, to occasionally execute individuals on a whim, etc. Nevertheless, one of Hobbes' aim was to warn sovereigns against over-using their power. Part of this came from his theory of human psychology - if the members of the commonwealth believe that they would be better off without the sovereign (rightly or wrongly), they will be motivated to overthrow him. Another part of Hobbes' warning, however, shows that the agreement individuals make on entering into the commonweath can involve a demand for more than just greater safety than would be found in a state of nature. They can demand a moderate level of well-being, and if the sovereign fails to provide that, then they will be justified in revolting.

Selected bibliography

- 1629. Translation of Thucydides's History of the Peloponnesian War

- 1650. The Elements of Law, Natural and Political, written in 1640 and comprising

- Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie

- De Corpore Politico

- 1651-8. Elementa philosophica

- 1642. De Cive (Latin)

- 1651. De Cive (English translation)

- 1655. De Corpore (Latin)

- 1656. De Corpore (English translation)

- 1658. De Homine (Latin)

- 1651. Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil.

- 1656. Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance

- 1668. Latin translation of the Leviathan

- 1681. Posthumously Behemoth, or The Long Parliament (written in 1668, unpublished at the request of the King).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- David Johnston; Thomas Hobbes. The Rhetoric of Leviathan. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986. ISBN 0691077177 ISBN 9780691077178

- Macpherson, C. B. The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke. Oxford, New York, Oxford University Press, 1967. ISBN 0198810849 ISBN 9780198810841

- Mintz, S. The Hunting of Leviathan. Cambridge [Eng.] University Press, 1962.

- Peters, R. Hobbes. Harmondsworth, Middlesex; Penguin Books, 1956.

- Skinner, Q. Reason and Rhetoric in the Philosophy of Hobbes. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521554365 ISBN 9780521554367

- J P Sommerville. Thomas Hobbes: Political Ideas in Historical Context. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. ISBN 0312079664 ISBN 9780312079666

- Sorell, T. Hobbes. London; New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986. ISBN 0710098456 ISBN 9780710098450

- Sorell, T. The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521410193 ISBN 9780521410199

- Sorell, Tom. Hobbes, Thomas. In E. Craig (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge, 2007

- Tuck, R. Hobbes. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0192876686 ISBN 9780192876683

External Links

- Works by Thomas Hobbes. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Luminarium: Thomas Hobbes Life, works, essays. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Hobbes at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Hobbes at The Philosophy pages. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Hobbes at the History of Economic Thought website. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Hobbes Moral and Political Philosophy at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Brief bio at Oregon State University. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- A Brief Life of Thomas Hobbes, 1588-1679 by John Aubrey. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Leviathan at The University of Adelaide. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Leviathan, available for free via Project Gutenberg. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- The Iliad, as translated by Hobbes, at the Online Library of Liberty. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- A short biography of Thomas Hobbes. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- A fairly complete and much more easily readable version of Parts 1 and 2 of Leviathan. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- Philosophy Sources on Internet EpistemeLinks. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- Guide to Philosophy on the Internet. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- Paideia Project Online. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- Project Gutenberg. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.