Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned corporation in the United States created by congressional charter in May 1933 to provide navigation, flood control, electricity generation, fertilizer manufacturing, and economic development in the Tennessee Valley, a region particularly impacted by the Great Depression. The TVA was envisioned not only as an electricity provider, but also as a regional economic development agency that would use federal experts and electricity to rapidly modernize the region's economy and society. The TVA's jurisdiction covers most of Tennessee, parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small slices of Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia. It is a political entity with a territory the size of a major state, and with some state powers (such as eminent domain), but unlike a state, it has no citizenry or elected officials. It was the first large regional planning agency of the federal government and remains the largest. Under the leadership of David Lilienthal ("Mr. TVA"), the Authority became a model for American efforts to modernize Third World agrarian societies.[1] It was promoted as an example of local democracy, cheap power, environmental conservation, and the peaceful use of energy and was even spoken of in utopian terms. Critics point to how those who were dispossessed and resettled were treated as indicative that justice was not always a priority. [2]

Overview

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the act creating the TVA on May 18, 1933. As a supplier of electric power, the agency was given authority to enter into long term (20 years) contracts for the sale of power to government agencies and private entities, to construct electric power transmission lines to areas not otherwise supplied and to establish rules and regulations for electricity retailing and distribution. The TVA is thus both a power supplier and a regulator.

Today the TVA is the nation's largest public power company, providing electric power to nearly 8.5 million customers in the Tennessee Valley. It acts primarily as an electric power wholesaler, selling to 158 retail power distributors and 61 directly served industrial or government customers. Power comes from dams providing hydroelectric power, fossil fuel plants, nuclear power plants, combustion turbines and wind turbines.

During the 1920s and the Great Depression years, Americans began to support the idea of government ownership of utilities, particularly hydroelectric power facilities. The concept of government-owned generation facilities selling to publicly owned distribution utilities was controversial and remains so today.[3]

Many believed privately owned power companies were charging too much for power, did not employ fair operating practices and were subject to abuse by their owners (utility holding companies), at the expense of consumers. During his presidential campaign, Roosevelt claimed that private utilities had "selfish purposes" and said, "Never shall the federal government part with its sovereignty or with its control of its power resources while I'm president of the United States." By forming utility holding companies, the private sector controlled 94 percent of generation by 1921, essentially unregulated. (This gave rise to Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA)). Many privates companies in the Tennessee Valley were bought by the federal government. Others shut down, unable to compete with the TVA. Government regulations were also passed to prevent competition with the TVA.

On the other hand, there were conservatives who believed the government should not participate in the electricity generation business, fearing government ownership would lead to the misuse of hydroelectric sites. The TVA was one of the first federal hydropower agencies, and today most of the nation's major hydropower systems are federally managed. Other attempts to create TVA-like regional agencies have failed, such as a proposed Columbia Valley Authority for the Columbia River.

Regional power consumers may benefit from lower-cost electricity supplied from TVA's network of 29 power-producing hydropower facilities. Supporters of the TVA, though, note that the agency's management of the Tennessee River system without appropriated federal funding saves federal taxpayers millions of dollars annually. Opponents, such as Dean Russell in The TVA Idea, in addition to condemning the project as being socialist, argued that the TVA created a "hidden loss" by preventing the creation of "factories and jobs that would have come into existence if the government had allowed the taxpayers to spend their money as they wished." Defenders note that the TVA is overwhelmingly popular in Tennessee among conservatives and liberals alike, as Barry Goldwater discovered in 1964, when he proposed selling the agency.[4]

One study says that public utilities are inadequate on maintenance. They note that federally owned power systems spend significantly less than private systems on this. They report that the TVA "spends only five percent of its revenues on maintenance." And, they say that as a consequence, ability to produce power suffers. Privately owned dams produce 20 percent more electricity than federally owned dams. They also report that the TVA charges its preferred customers (publicly owned utilities and cooperatives) more than private utilities charge the same class of customers. Also, they note when the public purchases bond issues from the TVA, they do not have an eye on the viability of the project but are, rather, basing their investment decision on the fact that repayment is guaranteed via taxation.[5]

The Supreme Court of the United States ruled the TVA to be constitutional in Ashwander v. TVA, 297 U.S. 288 (1936). The Court noted that regulating commerce among the states includes regulation of streams and that controlling floods is required for keeping streams navigable. The war powers also authorized the project. The argument before the court was that electricity generation was a by-product of navigation and flood control and therefore could be considered constitutional.

History

1930s

Even by Depression standards, the Tennessee Valley was in sad shape in 1933. Thirty percent of the population were affected by malaria, and the income was only $639 per year, with some families surviving on as little as $100 per year. Much of the land had been farmed too hard for too long, eroding and depleting the soil. Crop yields had fallen along with farm incomes. The best timber had been cut, with another 10 percent of forests being burnt each year.

The TVA was designed to modernize the region, using experts and electricity to combat human and economic problems.[7] TVA developed fertilizers, taught farmers ways to improve crop yields and helped replant forests, control forest fires, and improve habitat for fish and wildlife. The most dramatic change in Valley life came from TVA-generated electricity. Electric lights and modern appliances made life easier and farms more productive. Electricity also drew industries into the region, providing desperately needed jobs.

None of this was easy. The development of the dams displaced more than 15,000 families. Naturally, this caused resentment and anti-TVA sentiment in some rural communities. Many local landowners were suspicious of government agencies. But the TVA successfully introduced new agricultural methods into traditional farming communities by blending in and finding local champions.

A Tennessee farmer would not take advice from an official in a suit and tie, so TVA officials had to find leaders in the communities and convince them that crop rotation and the judicious application of fertilizers could restore soil fertility. Once they had convinced the leaders, the rest followed.

Beginning with its inception, the TVA was based in Knoxville, Tennessee in the old Federal Customs House at the corner of Clinch Avenue and Market Street. The building is now a museum. [8]

Employment policy

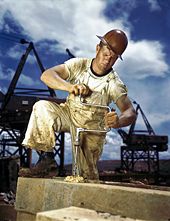

The unemployed were hired for conservation, economic development, and social programs such as a library service that operated for the surrounding area. The professional staff headquarters was composed of experts from outside the region. The workers were categorized into the usual racial and gender lines of the day. The TVA hired a few African-Americans for janitorial positions. The TVA recognized labor unions; its skilled and semi-skilled blue collar employees were unionized, a breakthrough in an area known for corporations hostile to miners' unions and textile unions. Women were excluded from construction work, although the TVA's cheap electricity attracted textile mills that hired mostly women.[9]

1940s

During World War II, the U.S. needed aluminum to build airplanes. Aluminum plants required huge amounts of electricity, and to provide the power, the TVA engaged in one of the largest hydropower construction programs ever undertaken in the U.S. Early in 1942, when the effort reached its peak, 12 hydroelectric and a steam plant were under construction at the same time, and design and construction employment reached a total of 28,000. The largest project of this period was the Fontana Dam Project. After negotiations led by Harry Truman ("I want aluminum. I don't care if I get it from Alcoa or Al Capone."), TVA purchased the land from Nantahala Power and Light, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Alcoa, and built Fontana Dam.

Electricity from Fontana was intended for Alcoa factories. By the time the dam generated power in early 1945, the electricity was used for another purpose in addition to aluminum manufacturing. TVA also provided much of the electricity needed for uranium separation using Calutrons at the Y-12 National Security Complex at Oak Ridge, as required for the Manhattan Project.

1950s

By the end of the war, TVA had completed a 650-mile (1,050-kilometer) navigation channel the length of the Tennessee River and had become the nation's largest electricity supplier. Even so, the demand for electricity was outstripping TVA's capacity to produce power from hydroelectric dams. Political interference kept TVA from securing additional federal appropriations to build coal-fired plants, so it sought the authority to issue bonds. Congress passed legislation in 1959 to make the TVA power system self-financing, and from that point on it would pay its own way.

1960s

The 1960s were years of unprecedented economic growth in the Tennessee Valley. Electric rates were among the nation's lowest and stayed low as TVA brought larger, more efficient generating units into service. Expecting the Valley's electric power needs to continue to grow, TVA began building nuclear reactors as a new source of cheap power. During this decade (and the 1970s), TVA was engaged in what was up to that time its most controversial project - the Tellico Dam Project. The project was initially conceived in the 1940s but not completed until 1979.

1970s and 1980s

Significant changes occurred in the economy of the Tennessee Valley and the nation, prompted by an international oil embargo in 1973 and accelerating fuel costs later in the decade. The average cost of electricity in the Tennessee Valley increased fivefold from the early 1970s to the early 1980s. With energy demand dropping and construction costs rising, TVA canceled several nuclear power plants, as did other utilities around the nation.

Marvin T. Runyon became chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority in January 1988. He claimed to reduce management layers, cut overhead costs by more than 30 percent, achieve cumulative savings and efficiency improvements of $1.8 billion. He said he revitalized the nuclear program, and instituted a rate freeze that continued for ten years.

The 1970s saw the last and most controversial of the TVA's large dam-reservoir projects, Tellico Dam.

1990s

As the electric-utility industry moved toward restructuring and deregulation, TVA began preparing for competition. It cut operating costs by nearly $800 million a year, reduced its workforce by more than half, increased the generating capacity of its plants, stopped building nuclear plants, and developed a plan to meet the energy needs of the Tennessee Valley through to the year 2020.

Current situation

TVA has recently made news by again reducing its workforce and by beginning new campaigns to improve its public image. It has also received acclaim from pro-nuclear organizations for its work to restart a previously mothballed nuclear reactor at Brown's Ferry Unit 1 (since completed). In 2005 the TVA announced its intention to construct an Advanced Pressurized Water Reactor at its Bellefonte site in Alabama (filing the necessary applications in November 2007), and in 2007 announced plans to complete the unfinished Unit 2 at Watts Bar. (TVA is the owner and operator of the Browns Ferry, Sequoyah and Watts Bar nuclear power plants.)

In 2004, TVA implemented recommendations from the Reservoir Operations Study (ROS) in how it operates the Tennessee River system (the nation's fifth largest).

TVA facilities

TVA's power mix as of 2004 was 11 fossil-powered plants, 29 hydroelectric dams, three nuclear power plants (with five reactors and one restarting), and six combustion turbine plants. TVA is one of the largest producers of electricity in the United States and acts as a regional grid reliability coordinator. Fossil fuel plants produced 62 percent of TVA’s total generation in fiscal year 2005, nuclear power 28 percent, and hydropower 10 percent. [10] TVA's Watts Bar reactor produces tritium as a byproduct for the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration, which requires tritium for nuclear weapons.

Dams

|

|

|

Fossil fuel plants

|

|

|

Nuclear power plants

TVA nuclear power plants include Browns Ferry, Sequoyah and Watts Bar.

Joint facilities

TVA also assists ALCOA's Tapoco/APGI in regulating several facilities, including Calderwood, Cheoah, Chilhowee and Santeetlah dams.

Administration

TVA's current headquarters are located in downtown Knoxville, with large administrative offices in Chattanooga and Nashville, Tenn.; and Muscle Shoals, Ala.

TVA as national symbol and political football

TVA was heralded by New Dealers and the New Deal Coalition not only as a successful economic development program for a depressed area but also as a democratic nation-building effort overseas because of its alleged grassroots inclusiveness as articulated by director David Lilienthal. The TVA was controversial in the 1930s. Historian Thomas McCraw concludes that Roosevelt "rescued the [power] industry from its own abuses" but "he might have done this much with a great deal less agitation and ill will."[11] New Dealers hoped to build numerous other TVAs around the country but were defeated by Wendell Willkie and the Conservative coalition in Congress. The valley authority model did not replace the limited-purpose water programs of the Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers. State-centered theorists hold that reformers are most likely to succeed during periods such as the New Deal era, when they are supported by a democratized polity and when they dominate Congress and the administration. However O'Neill shows that in river policy the strength of opposing interest groups also mattered.[12] The TVA bill was passed in 1933 because reformers like Norris skillfully coordinated action at potential choke points and weakened the already disorganized opposing electric power industry lobbyists. In 1936, however, after regrouping, opposing river lobbyists and conservative coalition congressmen took advantage of the New Dealers' spending mood by expanding the Army Corps' flood control program. They also helped defeat further valley authorities, the most promising of the New Deal water policy reforms.

When Democrats after 1945 proclaimed the TVA as a model for third-world countries to follow, conservative critics charged it was a top-heavy, centralized, technocratic venture that displaced locals and did so in insensitive ways. Thus, when the program was used as the basis for modernization programs in various parts of the third world during the Cold War, such as in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, its failure brought a backlash of cynicism toward modernization programs that has persisted.

Then-movie star Ronald Reagan had moved to television as the host and a frequent performer for General Electric Theater. He was fired by General Electric in 1964 in response to Reagan's televised speech "A Time for Choosing" supporting Goldwater's presidential campaign in part for criticizing TVA:[13]

"One such considered above criticism, sacred as motherhood, is TVA. This program started as a flood control project; the Tennessee Valley was periodically ravaged by destructive floods. The Army Engineers set out to solve this problem. They said that it was possible that once in 500 years there could be a total capacity flood that would inundate some 600,000 acres. Well, the engineers fixed that. They made a permanent lake which inundated a million acres. This solved the problem of floods, but the annual interest on the TVA debt is five times as great as the annual flood damage they sought to correct.

Of course, you will point out that TVA gets electric power from the impounded waters, and this is true, but today 85 percent of TVA's electricity is generated in coal burning steam plants. Now perhaps you'll charge that I'm overlooking the navigable waterway that was created, providing cheap barge traffic, but the bulk of the freight barged on that waterway is coal being shipped to the TVA steam plants, and the cost of maintaining that channel each year would pay for shipping all of the coal by rail, and there would be money left over."

Because TVA was a customer of General Electric at the time, General Electric fired him from the series. Reagan's final work as a professional actor was as host and performer from 1964 to 1965 on the television series Death Valley Days. [14] The publicity Reagan gained from his role in the Goldwater campaign, however, paved the way for his election as Governor of California in 1966.[15]

See also

- Tennessee

- New Deal

Notes

- ↑ see David Ekbladh, "'Mr. TVA:' Grass-Roots Development, David Lilienthal, and the Rise and Fall of the Tennessee Valley Authority as a Symbol for U.S. Overseas Development, 1933–1973." Diplomatic History 26 (3) (Summer 2002): 335-374.

- ↑ Michael J. McDonald and John Muldowny. TVA and the Dispossessed: The Resettlement of Population in the Norris Dam. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1982)

- ↑ Preston J. Hubbard. Origins of the TVA: The Muscle Shoals Controversy, 1920-1932. (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, [1961]. 2006. Library of Alabama Classics), 5-27.

- ↑ Rick Perlstein. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 226.

- ↑ CBO, Should the Federal Government Sell Electricity, Should the Federal Government Sell Electricity Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ↑ Much of this information comes from a government website in the public domain: Tennessee Valley Authority, From the New Deal to a New Century, A Short History of TVA Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ↑ Bruce J. Schulman. From Cotton Belt to Sun Belt: Policy, Economic Development, and the Transformation of the South, 1938-1980. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 183ff.

- ↑ East Tennessee Historical Society, ETHS Home, Home Page Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ↑ Jennifer Long, "Government Job Creation Programs-Lessons from the 1930s and 1940s." Journal of Economic Issues 33 (4) (1999): 903+.

- ↑ Tennessee Valley Authority, TVA Power Facts, TVA Power Facts Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ↑ Thomas K. McCraw. TVA and the power fight, 1933-1939. (Philadelphia, PA: J.P. Lippincott Co., 1971), 157.

- ↑ Karen M. O'Neill, "Why the TVA Remains Unique: Interest Groups and the Defeat of New Deal River Planning." Rural Sociology 67 (2) (2002): 163-182.

- ↑ University of Texas, A Time For Choosing (The Speech - October 27, 1964), Ronald Reagan, speech - "A Time for Choosing" Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ↑ IMBD, Ronald Reagan (I), Ronald Reagan (I) Internet Movie Database. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ↑ PBS, Ronald Regan Online News Hour: Ronald Reagan Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Biggs, David. "Reclamation Nations: The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's Role in Water Management and Nation Building in the Mekong Valley, 1945-1975." Comparative Technology Transfer and Society 4 (3) (December 2006): 225-246

- CBO. Should the Federal Government Sell Electricity. Should the Federal Government Sell Electricity Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Coligon, Richard A. Power Plays: Critical Events in the Institutionalism of the Tennessee Valley Authority. New York: SUNY Press, 1997. ISBN 9780585077086

- Creese, Walter L. TVA's Public Planning: The Vision, the Reality. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990. ISBN 0870496387 This book stresses utopian goals.

- East Tennessee Historical Societt. ETHS Home. Home Page Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Ekbladh, David. "'Mr. TVA:' Grass-Roots Development, David Lilienthal, and the Rise and Fall of the Tennessee Valley Authority as a Symbol for U.S. Overseas Development, 1933–1973." Diplomatic History 26 (3) (Summer 2002): 335-374.

- Hargrove, Erwin C., and Paul H. Conkin, eds. TVA Fifty Years of Grass-Roots Bureaucracy. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963 ISBN 9780252010866

- Hubbard, Preston J. Origins of the TVA: The Muscle Shoals Controversy, 1920-1932. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, [1961]. 2006. (Library of Alabama Classics) ISBN 0817352856

- IMBD. Ronald Reagan (I). Ronald Reagan (I) Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Lilienthal, David Eli. TVA: Democracy on the March. New York: Harper and brothers, 1944. This work promoted TVA for cheap power, grassroots regional democracy, environmental conservation, and the peaceful use of energy. It called TVA a model for the rest of USA and Europe.

- Long, Jennifer. "Government Job Creation Programs-Lessons from the 1930s and 1940s." Journal of Economic Issues 33 (4) (1999): 903+. This is an article on TVA in Knoxville

- McDonald, Michael J., and John Muldowny. TVA and the Dispossessed: The Resettlement of Population in the Norris Dam. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1982. ISBN 9780870493454. This book is highly critical of TVA.

- McCraw, Thomas K. TVA and the power fight, 1933-1939. Philadelphia, PA: J.P. Lippincott Co., 1971. ASIN: B000NUUPVG

- Morgan, Arthur E. The Making of the TVA. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1974. The Making of the TVA This book is authored by TVA's first chairman.

- Neuse, Steven M. "TVA at Age Fifty- Reflections and Retrospect." Public Administration Review 43 (6) (November - December 1983}: 491-499.

- Neuse, Steve M. David E. Lilienthal: The Journey of an American Liberal. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996. ISBN 9780870499401

- O'Neill, Karen M. "Why the TVA Remains Unique: Interest Groups and the Defeat of New Deal River Planning." Rural Sociology 67 (2) (2002): 163-182.

- PBS. Ronald Regan. Online News Hour: Ronald Reagan Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- Perlstein, Rick. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001 ISBN 9780809028597

- Reagan, Ronald, "A Time For Choosing (The Speech - October 27, 1964)" Ronald Reagan, speech - "A Time for Choosing" University of Texas. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Russell, Dean. The TVA Idea. Irving-On-Hudson, NY: The Foundation for Economic Education, 1949.

- Selznick, Philip. TVA and the Grass Roots: A Study in the Sociology of Formal Organization. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1949.TVA and the Grassroots Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Shapiro, Edward. "The Southern Agrarians and the Tennessee Valley Authority." American Quarterly 22 (4) (Winter 1970): 791-806. This article shows that these conservatives supported TVA as a counterpoint to northern big business.

- Schulman, Bruce J. From Cotton Belt to Sun Belt: Policy, Economic Development, and the Transformation of the South, 1938-1980. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991 ISBN 9781601297242

- Tennessee Valley Authority. From the New Deal to a New Century. A Short History of TVA Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Tennessee Valley Authority. TVA Power Facts. TVA Power Facts Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- White, Peter T. and W.E. Garrett, "The Mekong: River Of Terror And Hope." National Geographic (December 1968)

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.