Difference between revisions of "Tengu" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) m (→References) |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

==Artistic Representations== | ==Artistic Representations== | ||

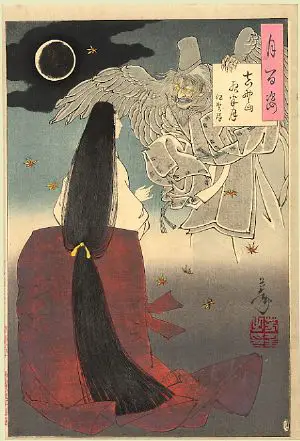

| − | [[Image:Yoshitoshi Kobayakawa Takakage.jpg|thumb|Kobayakawa Takakage debating with the ''tengu'' of mount Hiko, by | + | [[Image:Yoshitoshi Kobayakawa Takakage.jpg|thumb|Kobayakawa Takakage debating with the ''tengu'' of mount Hiko, by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. The ''tengu's'' nose protrudes just enough to differentiate him from an ordinary ''yamabushi''.]] |

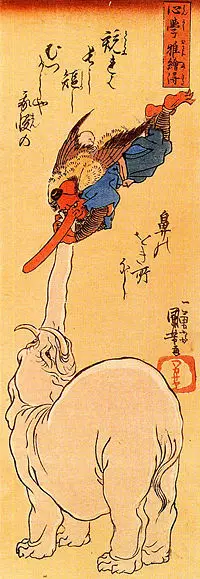

In Japanese art, the ''tengu'' is portrayed in a wide array of forms, though they usually can be placed somewhere on a continuum between large, monstrous birds and wholly [[anthropomorphism|anthropomorphized]] humanoids, the latter of which are often depicted with a red face and an unusually long nose.<ref>For some examples of the ''tengu'' in Japanese art (over and above those included in this article, see Stephen Addiss (ed.), ''Japanese Ghosts & Demons: art of the supernatural'', (New York: G. Braziller, Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1985). ISBN 0807611255.</ref> Early images of the ''tengu'' show them as kite-like beings that can take a human-like form, often retaining avian wings, head or beak. The ''tengu's'' long nose seems to have been conceived sometime in the 14th century, likely as a humanization of the original bird's bill.<ref>de Visser, pp. 61. The specific avian species that they appear to have derived from is the ''tobi'' or ''tonbi'' (鳶), the Japanese [[Black kite|black-eared kite]] (''Milvus migrans lineatus'').</ref> Indeed, the two depictions are seen as sufficiently discrete that each is referred to by a separate term, with "karasu tengu" (烏天狗) used to describe the avian ''tengu'' and "konoha tengu" (木の葉天狗) the humanoid form.<ref>Mark Schumacher, "Tengu", [http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/tengu.shtml A-Z Dictionary of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture]. Retrieved June 16, 2007.</ref> | In Japanese art, the ''tengu'' is portrayed in a wide array of forms, though they usually can be placed somewhere on a continuum between large, monstrous birds and wholly [[anthropomorphism|anthropomorphized]] humanoids, the latter of which are often depicted with a red face and an unusually long nose.<ref>For some examples of the ''tengu'' in Japanese art (over and above those included in this article, see Stephen Addiss (ed.), ''Japanese Ghosts & Demons: art of the supernatural'', (New York: G. Braziller, Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1985). ISBN 0807611255.</ref> Early images of the ''tengu'' show them as kite-like beings that can take a human-like form, often retaining avian wings, head or beak. The ''tengu's'' long nose seems to have been conceived sometime in the 14th century, likely as a humanization of the original bird's bill.<ref>de Visser, pp. 61. The specific avian species that they appear to have derived from is the ''tobi'' or ''tonbi'' (鳶), the Japanese [[Black kite|black-eared kite]] (''Milvus migrans lineatus'').</ref> Indeed, the two depictions are seen as sufficiently discrete that each is referred to by a separate term, with "karasu tengu" (烏天狗) used to describe the avian ''tengu'' and "konoha tengu" (木の葉天狗) the humanoid form.<ref>Mark Schumacher, "Tengu", [http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/tengu.shtml A-Z Dictionary of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture]. Retrieved June 16, 2007.</ref> | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

:In Japanese culture, a long nose signifies the alien, foreign, mysterious and sometimes frightening Other, who has foreign knowledge and superhuman power. ... The Tengu-type portrait of Commodore Perry utilises such an image to represent the way Japanese perceived him (and the power behind him) at the end of the Edo era.<ref>Nakar, 61. Indeed, many early images of Europeans (especially of the early Portuguese traders who visited Japan's shores) depict them with the characteristic phallic noses of the ''tengu''.</ref> | :In Japanese culture, a long nose signifies the alien, foreign, mysterious and sometimes frightening Other, who has foreign knowledge and superhuman power. ... The Tengu-type portrait of Commodore Perry utilises such an image to represent the way Japanese perceived him (and the power behind him) at the end of the Edo era.<ref>Nakar, 61. Indeed, many early images of Europeans (especially of the early Portuguese traders who visited Japan's shores) depict them with the characteristic phallic noses of the ''tengu''.</ref> | ||

| − | ''Tengu'' are commonly depicted holding magical {{nihongo|''hauchiwa''|羽団扇}}, fans made of feathers. In folk tales, these fans sometimes have the ability to grow or shrink a person's nose, but usually they are attributed the power to stir up great winds.<ref>For an extended discussion of this class of mystical artifacts, please see U. A. Casal's "The Lore of the Japanese Fan," ''Monumenta Nipponica'', Vol. 16 (1/2) (April 1960), pp. 53-117. He notes that the emblem of the Tengu King is "a feather-fan of flaming outline" (58 ff. 5).</ref> Various other strange accessories may be associated with ''tengu'', such as a type of tall, one-toothed '' | + | ''Tengu'' are commonly depicted holding magical {{nihongo|''hauchiwa''|羽団扇}}, fans made of feathers. In folk tales, these fans sometimes have the ability to grow or shrink a person's nose, but usually they are attributed the power to stir up great winds.<ref>For an extended discussion of this class of mystical artifacts, please see U. A. Casal's "The Lore of the Japanese Fan," ''Monumenta Nipponica'', Vol. 16 (1/2) (April 1960), pp. 53-117. He notes that the emblem of the Tengu King is "a feather-fan of flaming outline" (58 ff. 5).</ref> Various other strange accessories may be associated with ''tengu'', such as a type of tall, one-toothed ''geta'' sandal often called ''tengu-geta''.<ref>Mizuki 2001, p. 122.</ref> |

In addition to their frequent depictions in visual arts, tales of the tengu are common in both literature and folk tales ([[#In Literature and Popular Folk Tales|described below]]). | In addition to their frequent depictions in visual arts, tales of the tengu are common in both literature and folk tales ([[#In Literature and Popular Folk Tales|described below]]). | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

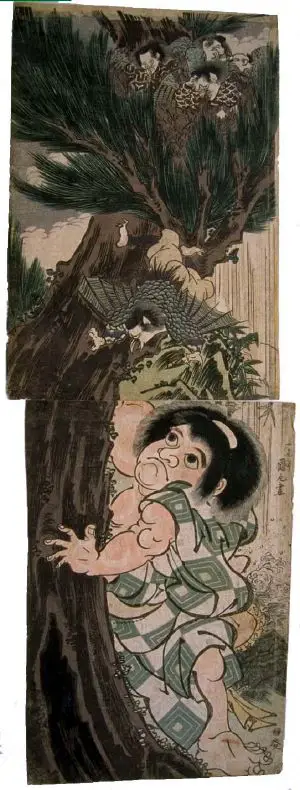

[[Image:Yoshitoshi Mount Yoshino Midnight Moon.jpg|thumb|right|Iga no Tsubone confronts the tormented spirit of Sasaki no Kiyotaka, by [[Yoshitoshi]]. Sasaki's ghost appears with the wings and claws of a ''tengu''.]] | [[Image:Yoshitoshi Mount Yoshino Midnight Moon.jpg|thumb|right|Iga no Tsubone confronts the tormented spirit of Sasaki no Kiyotaka, by [[Yoshitoshi]]. Sasaki's ghost appears with the wings and claws of a ''tengu''.]] | ||

| − | The ''[[Konjaku Monogatari]]'', a collection of stories published sometime during the late [[Heian Period]] (ca. 12th century CE), contains some of the earliest tales of ''tengu'', already characterized as they would be for centuries to come. These | + | The ''[[Konjaku Monogatari]]'', a collection of stories published sometime during the late [[Heian Period]] (ca. 12th century CE), contains some of the earliest tales of the ''tengu'', already characterized as they would be for centuries to come. These creatures are the troublesome opponents of Buddhism, who rob temples, mislead the pious with false images of Buddha,<ref>Mills describes one case where a ''tengu'' disguises itself as [[Amida Buddha]], 294.</ref> carry off monks and drop them in remote places,<ref>One such tale is summarized in Blacker (1963), where the monk (who is occupied in transcribing the [[Lotus Sutra]]) is kidnapped and taunted with foreign (and no doubt malignant) wine and fish, 79. For a more general (and thorough) introduction to the medieval tales of spirit abduction (not all of which are directed at religious figures, please consult the entirety of Blacker's 1967 article.</ref> possess women in an attempt to seduce holy men (or devout laity),<ref>Indeed, any "non-passive" female sexuality was seen (in patriarchal Japanese society) as being somehow dangerous and alien. This leads to an entire genre of literature concerning women possessed by the spirit of the ''tengu'', who then attempt to mislead pious men using their physical assets. See Tonomura, 147.</ref> and endow those who worship them with unholy power. They were often thought to disguise themselves as priests or nuns, but their true form seemed to be that of a kite (or other bird-like creature).<ref>de Visser, pp. 38-43.</ref> From a theological perspective, the ''tengu'' were seen to be manifestations of ''ma'' ([[Mara|Sanskrit: ''mara'']]), creatures of disorder and illusion whose sole purpose was to confound those on the quest for enlightenment.<ref>Wakabayashi, 481-482, 491-493.</ref> Intriguingly, though many of the tales and tropes described above created concrete spiritual opponents for Buddhism to define itself against, the image of the ''tengu'' was also be used to critique religious leaders, as in the {{nihongo|Tenguzōshi Emaki|天狗草子絵巻}} (ca. 1296), which depicted the Buddhist elites themselves transforming into the winged demons (as [[#Artistic Representations|discussed above]]). |

| − | Throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, an increasing number of accounts were produced | + | Throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, an increasing number of accounts were produced that described the various types of trouble that the ''tengu'' caused in the world. In many of these cases, they were now established as the ghosts of angry, vain, or heretical priests who had fallen on the "''tengu''-road" (天狗道, ''tengudō'').<ref>See Wakabayashi, 491-492 and ''passim'', for a description of this process.</ref> They began to possess people, especially women and girls, and speak through their mouths. In addition to their offenses against the general public, the demons described in the folktales of this period also turned their attention to the royal family. The [[Kojidan]] tells of an Empress who was possessed, and the [[Ōkagami]] reports that Emperor Sanjō was made blind by a ''tengu'', the ghost of a priest who resented the throne. <ref>de Visser, pp. 45-47. This ''tengu''-ghost eventually appeared and admitted to riding on the emperor's back with his wings clasped over the man's eyes.</ref> Further, one notorious ''tengu'' from the 12th century was himself understood to be the ghost of an emperor. The ''Tale of Hōgen'' tells the story of Emperor Sutoku, who was forced by his father to abandon the throne. When he later raised the [[Hōgen Rebellion]] to take back the country from Emperor Go-Shirakawa, he was defeated and exiled to Sanuki Province on [[Shikoku]]. According to legend, he died in torment, having sworn to haunt the nation of Japan as a great demon, and thus became a fearsome ''tengu'' with long nails and eyes like a kite's. <ref>de Visser, pp. 48-49.</ref> |

| − | + | In stories from the 13th century onward, the ''tengu'' were now understood to be interested in kidnapping children and young adults—especially those who trespassed (whether knowingly or not) into their sanctuaries.<ref>Blacker (1967), 116.</ref> The children (typically boys) were often returned, while the priests would be found tied to the tops of trees or in other high places. All of the ''tengu's'' victims, however, would come back in a state of near death or madness, sometimes after having been tricked into eating animal dung. <ref>de Visser, pp. 55-57.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

The ''tengu'' of this period were often conceived of as the ghosts the arrogant, and as a result the creatures have became strongly associated with vanity and pride. Today the Japanese expression ''tengu ni naru'', literally, "he is turning into a ''tengu''", is still used to describe a conceited person.<ref>Mizuki 2001.</ref> | The ''tengu'' of this period were often conceived of as the ghosts the arrogant, and as a result the creatures have became strongly associated with vanity and pride. Today the Japanese expression ''tengu ni naru'', literally, "he is turning into a ''tengu''", is still used to describe a conceited person.<ref>Mizuki 2001.</ref> | ||

==Great and Small Demons== | ==Great and Small Demons== | ||

| − | In the ''[[Genpei Jōsuiki]]'', written in the late [[Kamakura period]], a god appears to Go-Shirakawa and gives a detailed account of ''tengu'' ghosts. He says that they fall onto the ''tengu'' road because, as Buddhists, they cannot go to [[Di Yu|Hell]], yet as people with bad principles, they also cannot go to [[Nirvana|Heaven]]. He describes the appearance of different types of ''tengu'': the ghosts of priests, nuns, ordinary men, and ordinary women, all of whom in life possessed excessive pride. The god introduces the notion that not all ''tengu'' are equal; knowledgeable men become {{nihongo|''daitengu''|大天狗, ''big tengu''}}, but ignorant ones become {{nihongo|''kotengu''|小天狗, ''small tengu''}}.<ref>de Visser, pp. 51-53.</ref> | + | In the ''[[Genpei Jōsuiki]]'', written in the late [[Kamakura period]] (ca. 1300 C.E.), a god appears to Go-Shirakawa and gives a detailed account of ''tengu'' ghosts. He says that they fall onto the ''tengu'' road because, as Buddhists, they cannot go to [[Di Yu|Hell]], yet as people with bad principles, they also cannot go to [[Nirvana|Heaven]]. He describes the appearance of different types of ''tengu'': the ghosts of priests, nuns, ordinary men, and ordinary women, all of whom in life possessed excessive pride. The god introduces the notion that not all ''tengu'' are equal; knowledgeable men become {{nihongo|''daitengu''|大天狗, ''big tengu''}}, but ignorant ones become {{nihongo|''kotengu''|小天狗, ''small tengu''}}.<ref>de Visser, pp. 51-53.</ref> |

| − | The philosopher [[Hayashi Razan]] lists the greatest of these ''daitengu'' as [[Sōjōbō]] of [[Mount Kurama|Kurama]], [[Tarōbō]] of [[Mount Atago|Atago]], and Jirōbō of [[Hira Mountains|Hira]].<ref>de Visser, pp. 71.</ref> The demons of Kurama and Atago are among the most famous ''tengu''.<ref>Mizuki 2001.</ref> | + | The philosopher [[Hayashi Razan]] (1583–1657) lists the greatest of these ''daitengu'' as [[Sōjōbō]] of [[Mount Kurama|Kurama]], [[Tarōbō]] of [[Mount Atago|Atago]], and Jirōbō of [[Hira Mountains|Hira]].<ref>de Visser, pp. 71.</ref> The demons of Kurama and Atago are among the most famous ''tengu''.<ref>Mizuki 2001.</ref> It is notable that, despite Razan's writing in the culturally-advanced [[Tokugawa period]], it was still seen as entirely appropriate for an intelligent, government-employed Confucian scholar to write a credulous account of these spiritual beings.<ref>Hansen, 354.</ref> |

A section of the ''Tengu Meigikō'', later quoted by [[Inoue Enryō]], lists the ''daitengu'' in this order: | A section of the ''Tengu Meigikō'', later quoted by [[Inoue Enryō]], lists the ''daitengu'' in this order: | ||

| − | *{{nihongo|Sōjōbō|僧正坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Sōjōbō|僧正坊}} of Mount Kurama |

| − | *{{nihongo|Tarōbō|太郎坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Tarōbō|太郎坊}} of Mount Atago |

| − | *{{nihongo|Jirōbō|二郎坊}} of the | + | *{{nihongo|Jirōbō|二郎坊}} of the Hira Mountains |

| − | *{{nihongo|Sanjakubō|三尺坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Sanjakubō|三尺坊}} of Mount Akiba |

| − | *{{nihongo|Ryūhōbō|笠鋒坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Ryūhōbō|笠鋒坊}} of Mount Kōmyō |

| − | *{{nihongo|Buzenbō|豊前坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Buzenbō|豊前坊}} of Mount Hiko |

| − | *{{nihongo|Hōkibō|伯耆坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Hōkibō|伯耆坊}} of Mount Daisen |

| − | *{{nihongo|Myōgibō|妙義坊}} of Mount Ueno ( | + | *{{nihongo|Myōgibō|妙義坊}} of Mount Ueno (Ueno Park) |

| − | *{{nihongo|Sankibō|三鬼坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Sankibō|三鬼坊}} of Itsukushima |

| − | *{{nihongo|Zenkibō|前鬼坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Zenkibō|前鬼坊}} of Mount Ōmine |

| − | *{{nihongo|Kōtenbō|高天坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Kōtenbō|高天坊}} of Katsuragi |

| − | *{{nihongo|Tsukuba-hōin|筑波法印}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Tsukuba-hōin|筑波法印}} of Hitachi Province |

| − | *{{nihongo|Daranibō|陀羅尼坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Daranibō|陀羅尼坊}} of Mount Fuji |

| − | *{{nihongo|Naigubu|内供奉}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Naigubu|内供奉}} of Mount Takao |

| − | *{{nihongo|Sagamibō|相模坊}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Sagamibō|相模坊}} of Shiramine |

| − | *{{nihongo|Saburō|三郎}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Saburō|三郎}} of Mount Iizuna |

| − | *{{nihongo|Ajari|阿闍梨}} of | + | *{{nihongo|Ajari|阿闍梨}} of Higo Province<ref>de Visser, p. 82; most kanji and some name corrections retrieved from [http://www1.bbweb-arena.com/baron/tengu.html here].</ref> |

| − | ''Daitengu'' are often pictured in a more human-like form than their underlings, and due to their long noses, they may also called {{nihongo|''hanatakatengu''|鼻高天狗, ''tall-nosed tengu''}}. ''Kotengu'' may conversely be depicted as more bird-like. They are sometimes called {{nihongo|''karasu-tengu''|烏天狗, ''crow tengu''}}, or {{nihongo|''koppa-'' or''konoha-tengu''|木葉天狗, 木の葉天狗''foliage tengu''}}.<ref>Mizuki 2001</ref> | + | ''Daitengu'' are often pictured in a more human-like form than their underlings, and due to their long noses, they may also called {{nihongo|''hanatakatengu''|鼻高天狗, ''tall-nosed tengu''}}. ''Kotengu'' may conversely be depicted as more bird-like. They are sometimes called {{nihongo|''karasu-tengu''|烏天狗, ''crow tengu''}}, or {{nihongo|''koppa-'' or''konoha-tengu''|木葉天狗, 木の葉天狗''foliage tengu''}}.<ref>Mizuki 2001</ref> Inoue Enryō described two kinds of ''tengu'' in his ''Tenguron'': the great ''daitengu'', and the small, bird-like ''konoha-tengu'' who live in ''Cryptomeria'' trees. The ''konoha-tengu'' are noted in a book from 1746 called the {{nihongo|''Shokoku Rijin Dan''|諸国里人談}}, as bird-like creatures with wings two meters across which were seen catching fish in the Ōi River, but this name rarely appears in literature otherwise.<ref>de Visser, p. 84; Mizuki 2003, p. 70. The term ''konoha-tengu'' is often mentioned in English texts as a synonym for ''daitengu'', but this appears to be a widely-repeated mistake which is not corroborated by Japanese-language sources.</ref> |

| − | + | Despite this fairly clear dichotomy, some creatures that do not fit either of the classic images (the bird-like or ''yamabushi''types) are still sometimes referred to as ''tengu''. For example, ''tengu'' in the guise of wood-spirits may be called {{nihongo|''guhin'' (occasionally written ''kuhin'')|狗賓|''dog guests''}}, but this word can also refer to ''tengu'' with canine mouths or other features.<ref>Mizuki 2001</ref> The people of Kōchi Prefecture on [[Shikoku]] believe in a creature called {{nihongo|''shibaten'' or ''shibatengu''|シバテン, 芝天狗, ''lawn tengu''}}, but this is a small child-like being who loves ''[[sumo|sumō]]'' wrestling and sometimes dwells in the water, and is generally considered one of the many kinds of ''[[Kappa (folklore)|kappa]]''.<ref>Mizuki, Mujara 4, p. 94</ref> Another water-dwelling ''tengu'' is the {{nihongo|''kawatengu''|川天狗, ''river tengu''}} of the Greater Tokyo Area. This creature is rarely seen, but it is believed to create strange fireballs and to be a nuisance to fishermen. <ref>Mizuki, Mujara 1, p. 38; [http://www.nichibun.ac.jp/cgi-bin/YoukaiDB/kwaiiList.cgi?Name=%1b%24B%25%2b%25o%25F%25s%250%1b%28B&Pref=&Area=%c1%b4%b9%f1 Kaii*Yōkai Denshō Database: Kawatengu]</ref> | |

==Protective Spirits and Benevolent Deities== | ==Protective Spirits and Benevolent Deities== | ||

| Line 217: | Line 215: | ||

| chapter = ''Tengu'', the Mountain Goblin | | chapter = ''Tengu'', the Mountain Goblin | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | * {{cite journal | ||

| + | | last = Hansen | ||

| + | | first = Wilburn | ||

| + | | title = "The Medium is the Message: Hirata Atsutane's Ethnography of the World Beyond" | ||

| + | | journal = History of Religions | ||

| + | | volume = 45 | ||

| + | | pages = pp. 337-372 | ||

| + | | date = 2006 }} | ||

* {{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| last = Mills | | last = Mills | ||

| Line 263: | Line 269: | ||

| pages = pp. 129-154 | | pages = pp. 129-154 | ||

| date = 1994 }} | | date = 1994 }} | ||

| + | * {{cite journal | ||

| + | | last = Wakabayashi | ||

| + | | first = Haruko | ||

| + | | title = "From Conqueror of Evil to Devil King: Ryogen and Notions of Ma in Medieval Japanese Buddhism" | ||

| + | | journal = Monumenta Nipponica | ||

| + | | volume = 54 | ||

| + | | issue = 4 | ||

| + | | pages = pp. 481-507 | ||

| + | | date = Winter 1999 }} | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 01:47, 17 June 2007

Tengu (天狗 "heavenly dogs") are a class of supernatural creatures found in Japanese folklore, art, theater, literature and religious mythology. They are one of the best known classes of yōkai (monster-spirits), though this classification does not prevent their occasional worship as Shinto kami (revered spirits or gods). Although the term tengu was derived from the Chinese designation for a type of dog-like demons (天狗 (tian gou)), the Japanese spirits were originally thought to take the forms of birds of prey, such that they are traditionally depicted with both human and avian characteristics. In the earliest sources, tengu were actually pictured with beaks, but, in later depictions, these features have often been anthropomorphized into unnaturally long noses. In the modern imagination (and especially in artistic works), this single characteristic (the expansive proboscis) is the most definitive aspect of the tengu.

Though the term used to describe these beings is of Chinese origin, their particular characterization is distinctively Japanese. Indeed, the precise origin of these crafty (oftentimes dangerous) bird-men is unknown, implying that the understanding of them developed through a process of importing myths from China (and, indirectly, from India), and then localizing them through overt syncretism and reinterpretations in popular folklore (see below). In this context, Japanese Buddhists long held that the tengu were disruptive demons and harbingers of war (much like their Chinese prototypes). Over time, this overtly negative evaluation was softened somewhat, as the Buddhists came to acknowledge the popular conception of these spirits as morally-ambivalent protectors of the mountains and forests, who were as likely to bring windfalls as calamities to humans intruding upon their domains.[1].

The tengu, due to their professed affinity with the natural world, are associated with the ascetic practices known as Shugendō (a path of nature-based mysticism), and, in the visual arts, are often depicted in the distinctive garb of its followers, the yamabushi.

Artistic Representations

In Japanese art, the tengu is portrayed in a wide array of forms, though they usually can be placed somewhere on a continuum between large, monstrous birds and wholly anthropomorphized humanoids, the latter of which are often depicted with a red face and an unusually long nose.[2] Early images of the tengu show them as kite-like beings that can take a human-like form, often retaining avian wings, head or beak. The tengu's long nose seems to have been conceived sometime in the 14th century, likely as a humanization of the original bird's bill.[3] Indeed, the two depictions are seen as sufficiently discrete that each is referred to by a separate term, with "karasu tengu" (烏天狗) used to describe the avian tengu and "konoha tengu" (木の葉天狗) the humanoid form.[4]

Some of the earliest representations of tengu appear in Japanese picture scrolls, such as the Tenguzōshi Emaki (天狗草子絵巻), painted ca. 1296, which parodies high-ranking priests by endowing them the hawk-like beaks of tengu demons.[5] Indeed, tengu are often pictured taking the shape of priests. Most specifically, as of the beginning in the 13th century, tengu came to be associated in particular with the yamabushi, the mountain ascetics who practice Shugendō.[6] The association soon found its way into Japanese art, where tengu are most frequently depicted in the yamabushi's distinctive costume, which includes a small black cap (頭襟 tokin) and a pom-pommed sash (結袈裟 yuigesa).[7] Further, just as the image of the tengu was used to critique the ecclesiastical elites in the picture scroll described above, it was also used as a visual analogy representing the dangerous influence of the (long-nosed) foreigners who began to interact with Japan in the Edo period. In one instance, the British Commodore Perry was caricaturized in just such a fashion:

- In Japanese culture, a long nose signifies the alien, foreign, mysterious and sometimes frightening Other, who has foreign knowledge and superhuman power. ... The Tengu-type portrait of Commodore Perry utilises such an image to represent the way Japanese perceived him (and the power behind him) at the end of the Edo era.[8]

Tengu are commonly depicted holding magical hauchiwa (羽団扇), fans made of feathers. In folk tales, these fans sometimes have the ability to grow or shrink a person's nose, but usually they are attributed the power to stir up great winds.[9] Various other strange accessories may be associated with tengu, such as a type of tall, one-toothed geta sandal often called tengu-geta.[10]

In addition to their frequent depictions in visual arts, tales of the tengu are common in both literature and folk tales (described below).

Origins

<incorporate?> The tengu's long noses ally them with the Shinto deity Sarutahiko, who is described in the Japanese historical text, the Nihon Shoki, with a similar facial protuberance measuring seven hand-spans in length.[11] In village festivals the two figures are often portrayed with identical red, phallic-nosed mask designs.[12] <??>

The term tengu and the characters used to write it are borrowed from the name of a fierce demon from Chinese folklore called tiāngoǔ. Chinese literature assigns this creature a variety of descriptions, but most often it is a fierce and anthropophagous canine monster that resembles a shooting star or comet. It makes a noise like thunder and brings war wherever it falls. One account from the Shù Yì Jì (述異記, "A Collection of Bizarre Stories"), written in 1791, describes a dog-like tiāngoǔ with a sharp beak and an upright posture, but usually tiāngoǔ bear little resemblance to their Japanese counterparts.[13]

The 23rd chapter of the Nihon Shoki, written in 720, is generally held to contain the first recorded mention of tengu in Japan. In this account a large shooting star appears and is identified by a Buddhist priest as a "heavenly dog", and much like the tiāngoǔ of China, the star precedes a military uprising. Although the Chinese characters for tengu are used in the text, accompanying phonetic furigana characters give the reading as amatsukitsune (heavenly fox). M.W. de Visser speculated that the early Japanese tengu may represent a conglomeration of two Chinese spirits: the tiāngoǔ and the fox spirits called huli jing.[14]

How the tengu was transformed from a dog-meteor into a bird-man is not clear. Some Japanese scholars have supported the theory that the tengu's image derives from that of the Hindu eagle deity Garuda, who was pluralized in Buddhist scripture as one of the major races of non-human beings. Like the tengu, the garuda are often portrayed in a human-like form with wings and a bird's beak. The name tengu seems to be written in place of that of the garuda in a Japanese sutra called the Enmyō Jizō Kyō (延命地蔵経), but this was likely written in the Edo period, long after the tengu's image was established. At least one early story in the Konjaku Monogatari describes a tengu carrying off a dragon, which is reminiscent of the garuda's feud with the nāga serpents. In other respects, however, the tengu's original behavior differs markedly from that of the garuda, which is generally friendly towards Buddhism. De Visser has speculated that the tengu may be descended from an ancient Shinto bird-demon which was syncretized with both the garuda and the tiāngoǔ when Buddhism arrived in Japan. However, he found little evidence to support this idea.[15]

A later version of the Kujiki, an ancient Japanese historical text, writes the name of Amanozako, a monstrous female deity born from the god Susanoo's spat-out ferocity, with characters meaning tengu deity (天狗神). The book describes Amanozako as a raging creature capable of flight, with the body of a human, the head of a beast, a long nose, long ears, and long teeth that can chew through swords. An 18th century book called the Tengu Meigikō (天狗名義考) suggests that this goddess may be the true predecessor of the tengu, but the date and authenticity of the Kujiki, and of that edition in particular, remain disputed.[16]

Evil Spirits and Angry Ghosts

The Konjaku Monogatari, a collection of stories published sometime during the late Heian Period (ca. 12th century CE), contains some of the earliest tales of the tengu, already characterized as they would be for centuries to come. These creatures are the troublesome opponents of Buddhism, who rob temples, mislead the pious with false images of Buddha,[17] carry off monks and drop them in remote places,[18] possess women in an attempt to seduce holy men (or devout laity),[19] and endow those who worship them with unholy power. They were often thought to disguise themselves as priests or nuns, but their true form seemed to be that of a kite (or other bird-like creature).[20] From a theological perspective, the tengu were seen to be manifestations of ma (Sanskrit: mara), creatures of disorder and illusion whose sole purpose was to confound those on the quest for enlightenment.[21] Intriguingly, though many of the tales and tropes described above created concrete spiritual opponents for Buddhism to define itself against, the image of the tengu was also be used to critique religious leaders, as in the Tenguzōshi Emaki (天狗草子絵巻) (ca. 1296), which depicted the Buddhist elites themselves transforming into the winged demons (as discussed above).

Throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, an increasing number of accounts were produced that described the various types of trouble that the tengu caused in the world. In many of these cases, they were now established as the ghosts of angry, vain, or heretical priests who had fallen on the "tengu-road" (天狗道, tengudō).[22] They began to possess people, especially women and girls, and speak through their mouths. In addition to their offenses against the general public, the demons described in the folktales of this period also turned their attention to the royal family. The Kojidan tells of an Empress who was possessed, and the Ōkagami reports that Emperor Sanjō was made blind by a tengu, the ghost of a priest who resented the throne. [23] Further, one notorious tengu from the 12th century was himself understood to be the ghost of an emperor. The Tale of Hōgen tells the story of Emperor Sutoku, who was forced by his father to abandon the throne. When he later raised the Hōgen Rebellion to take back the country from Emperor Go-Shirakawa, he was defeated and exiled to Sanuki Province on Shikoku. According to legend, he died in torment, having sworn to haunt the nation of Japan as a great demon, and thus became a fearsome tengu with long nails and eyes like a kite's. [24]

In stories from the 13th century onward, the tengu were now understood to be interested in kidnapping children and young adults—especially those who trespassed (whether knowingly or not) into their sanctuaries.[25] The children (typically boys) were often returned, while the priests would be found tied to the tops of trees or in other high places. All of the tengu's victims, however, would come back in a state of near death or madness, sometimes after having been tricked into eating animal dung. [26]

The tengu of this period were often conceived of as the ghosts the arrogant, and as a result the creatures have became strongly associated with vanity and pride. Today the Japanese expression tengu ni naru, literally, "he is turning into a tengu", is still used to describe a conceited person.[27]

Great and Small Demons

In the Genpei Jōsuiki, written in the late Kamakura period (ca. 1300 C.E.), a god appears to Go-Shirakawa and gives a detailed account of tengu ghosts. He says that they fall onto the tengu road because, as Buddhists, they cannot go to Hell, yet as people with bad principles, they also cannot go to Heaven. He describes the appearance of different types of tengu: the ghosts of priests, nuns, ordinary men, and ordinary women, all of whom in life possessed excessive pride. The god introduces the notion that not all tengu are equal; knowledgeable men become daitengu (大天狗, big tengu), but ignorant ones become kotengu (小天狗, small tengu).[28]

The philosopher Hayashi Razan (1583–1657) lists the greatest of these daitengu as Sōjōbō of Kurama, Tarōbō of Atago, and Jirōbō of Hira.[29] The demons of Kurama and Atago are among the most famous tengu.[30] It is notable that, despite Razan's writing in the culturally-advanced Tokugawa period, it was still seen as entirely appropriate for an intelligent, government-employed Confucian scholar to write a credulous account of these spiritual beings.[31]

A section of the Tengu Meigikō, later quoted by Inoue Enryō, lists the daitengu in this order:

- Sōjōbō (僧正坊) of Mount Kurama

- Tarōbō (太郎坊) of Mount Atago

- Jirōbō (二郎坊) of the Hira Mountains

- Sanjakubō (三尺坊) of Mount Akiba

- Ryūhōbō (笠鋒坊) of Mount Kōmyō

- Buzenbō (豊前坊) of Mount Hiko

- Hōkibō (伯耆坊) of Mount Daisen

- Myōgibō (妙義坊) of Mount Ueno (Ueno Park)

- Sankibō (三鬼坊) of Itsukushima

- Zenkibō (前鬼坊) of Mount Ōmine

- Kōtenbō (高天坊) of Katsuragi

- Tsukuba-hōin (筑波法印) of Hitachi Province

- Daranibō (陀羅尼坊) of Mount Fuji

- Naigubu (内供奉) of Mount Takao

- Sagamibō (相模坊) of Shiramine

- Saburō (三郎) of Mount Iizuna

- Ajari (阿闍梨) of Higo Province[32]

Daitengu are often pictured in a more human-like form than their underlings, and due to their long noses, they may also called hanatakatengu (鼻高天狗, tall-nosed tengu). Kotengu may conversely be depicted as more bird-like. They are sometimes called karasu-tengu (烏天狗, crow tengu), or koppa- orkonoha-tengu (木葉天狗, 木の葉天狗foliage tengu).[33] Inoue Enryō described two kinds of tengu in his Tenguron: the great daitengu, and the small, bird-like konoha-tengu who live in Cryptomeria trees. The konoha-tengu are noted in a book from 1746 called the Shokoku Rijin Dan (諸国里人談), as bird-like creatures with wings two meters across which were seen catching fish in the Ōi River, but this name rarely appears in literature otherwise.[34]

Despite this fairly clear dichotomy, some creatures that do not fit either of the classic images (the bird-like or yamabushitypes) are still sometimes referred to as tengu. For example, tengu in the guise of wood-spirits may be called guhin (occasionally written kuhin) (狗賓 dog guests), but this word can also refer to tengu with canine mouths or other features.[35] The people of Kōchi Prefecture on Shikoku believe in a creature called shibaten or shibatengu (シバテン, 芝天狗, lawn tengu), but this is a small child-like being who loves sumō wrestling and sometimes dwells in the water, and is generally considered one of the many kinds of kappa.[36] Another water-dwelling tengu is the kawatengu (川天狗, river tengu) of the Greater Tokyo Area. This creature is rarely seen, but it is believed to create strange fireballs and to be a nuisance to fishermen. [37]

Protective Spirits and Benevolent Deities

The Shasekishū, a book of Buddhist parables from the Kamakura period, makes a point of distinguishing between good and bad tengu. The book explains that the former are in command of the latter and are the protectors, not opponents, of Buddhism - although the flaw of pride or ambition has caused them to fall onto the demon road, they remain the same basically good, dharma-abiding persons they were in life.[38]

The tengu's unpleasant image continued to erode in the 17th century. Some stories now presented them as much less malicious, protecting and blessing Buddhist institutions rather than menacing them or setting them on fire. According to a legend in the 18th-century Kaidan Toshiotoko (怪談登志男), a tengu took the form of a yamabushi and faithfully served the abbot of a Zen monastery until the man guessed his attendant's true form. The tengu's wings and huge nose then reappeared. The tengu requested a piece of wisdom from his master and left, but he continued, unseen, to provide the monastery with miraculous aid.[39]

In the 18th and 19th centuries, tengu came to be feared as the vigilant protectors of certain forests. In the 1764 collection of strange stories Sanshu Kidan (三州奇談), a tale tells of a man who wanders into a deep valley while gathering leaves, only to be faced with a sudden and ferocious hailstorm. A group of peasants later tell him that he was in the valley where the guhin live, and anyone who takes a single leaf from that place will surely die. In the Sōzan Chomon Kishū (想山著聞奇集), written in 1849, the author describes the customs of the wood-cutters of Mino Province, who used a sort of rice cake called kuhin-mochi to placate the tengu, who would otherwise perpetrate all sorts of mischief. In other provinces a special kind of fish called okoze was offered to the tengu by woodsmen and hunters, in exchange for a successful day's work.[40] The people of Ishikawa Prefecture have until recently believed that the tengu loathe mackerel, and have used this fish as a charm against kidnappings and hauntings by the mischievous spirits. [41]

Tengu are worshipped as beneficial kami (gods or revered spirits) in various Japanese religious cults. For example, the tengu Saburō of Izuna is worshipped on that mountain and various others as Izuna Gongen (飯綱権現, incarnation of Izuna), one of the primary deities in the Izuna Shugen cult, which also has ties to fox sorcery and the Dakini of Tantric Buddhism. Izuna Gongen is depicted as a beaked, winged figure with snakes wrapped around his limbs, surrounded by a halo of flame, riding on the back of a fox and brandishing a sword. Worshippers of tengu on other sacred mountains have adopted similar images for their deities, such as Sanjakubō (三尺坊) or Akiba Gongen (秋葉権現) of Akiba and Dōryō Gongen (道了権現) of Saijō-ji Temple in Odawara.[42]

In Literature and Popular Folk Tales

Tengu appear frequently in the orally-transmitted tales collected by Japanese folklorists. As these stories are often humorous, they tend to portray tengu as ridiculous creatures who are easily tricked or confused by humans. Some common folk tales in which tengu appear include:

- "The Tengu's Magic Cloak" (天狗の隠れみの Tengu no Kakuremino): A boy looks through an ordinary piece of bamboo and pretends he can see distant places. A tengu, overwhelmed by curiosity, offers to trade it for a magic straw cloak that renders the wearer invisible. Having duped the tengu, the boy continues his mischief while wearing the cloak.[43]

- "The Old Man's Lump Removed" (瘤取り爺さん Kobu-tori Jiisan): An old man has a lump or tumor on his face. In the mountains he encounters a band of tengu making merry and joins their dancing. He pleases them so much that they take the lump off his face, thinking that he will want it back and join them the next night. An unpleasant neighbor, who also has a lump, hears of the old man's good fortune and attempts to repeat it. The tengu, however, simply give him the first lump in addition to his own, either to keep their bargain, or because they are disgusted by his bad dancing.[44]

- "The Tengu's Fan" (天狗の羽団扇 Tengu no Hauchiwa) A scoundrel obtains a tengu's magic fan, which can shrink or grow noses. He secretly uses this item to grotesquely extend the nose of a rich man's daughter, and then shrinks it again in exchange for her hand in marriage. Later he accidentally fans himself while he dozes, and his nose grows so long it reaches heaven, resulting in painful misfortune for him.[45]

- "The Tengu's Gourd" (天狗の瓢箪 "Tengu no Hyōtan"): A gambler meets a tengu, who asks him what he is most frightened of. The gambler lies, claiming that he is terrified of gold or mochi. The tengu answers truthfully that he is frightened of a kind of plant or some other mundane item. The tengu, thinking he is playing a cruel trick, then causes money or rice cakes to rain down on the gambler. The gambler is of course delighted and proceeds to scare the tengu away with the thing he fears most. The gambler then obtains the tengu's magic gourd (or another treasured item) that was left behind.[46]

- A tengu bothers a woodcutter, showing off his supernatural abilities by guessing everything the man is thinking. The woodcutter swings his axe, and a splinter of wood hits the tengu on the nose. The tengu flees in terror, exclaiming that humans are dangerous creatures who can do things without thinking about them.[47]

<go into the supernatural literature of the Edo period here>

Modern Fiction

Profoundly entrenched in the Japanese imagination for centuries, tengu continue to be popular subjects in modern fiction, both in Japan and increasingly in other countries. They often appear among the many characters and creatures featured in Japanese cinema, animation, comics, and video games.

Martial Arts

During the 14th century, the tengu began to trouble the world outside of the Buddhist clergy, and like their ominous ancestors the tiāngoǔ, the tengu became creatures associated with war.[48] Legends eventually ascribed to them great knowledge in the art of skilled combat.

This reputation seems to have its origins in a legend surrounding the famous warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune. When Yoshitsune was a young boy going by the name of Ushiwaka-maru, his father, Yoshitomo, was assassinated by the Taira clan. Taira no Kiyomori, head of the Taira, allowed the child to survive on the grounds that he be exiled to the temple on Mount Kurama and become a monk. But one day in the Sōjō-ga-dani Valley, Ushiwaka encountered the mountain's tengu, Sōjōbō. This spirit taught the boy the art of swordsmanship so that he might bring vengeance on the Taira.[49]

Originally the actions of this tengu were portrayed as another attempt by demons to throw the world into chaos and war, but as Yoshitsune's renown as a legendary warrior increased, his monstrous teacher came to be depicted in a much more sympathetic and honorable light. In one of the most famous renditions of the story, the Noh play Kurama Tengu, Ushiwaka is the only person from his temple who does not give up an outing in disgust at the sight of a strange yamabushi. Sōjōbō thus befriends the boy and teaches him out of sympathy for his plight.[50]

Two stories from the 19th century continue this theme: In the Sōzan Chomon Kishū, a boy is carried off by a tengu and spends three years with the creature. He comes home with a magic gun that never misses a shot. A story from Inaba Province, related by Inoue Enryō, tells of a girl with poor manual dexterity who is suddenly possessed by a tengu. The spirit wishes to rekindle the declining art of swordsmanship in the world. Soon a young samurai appears to whom the tengu has appeared in a dream, and the possessed girl instructs him as an expert swordsman.[51] Some rumors surrounding the ninja indicate that they were also instructed by the tengu.[52]

Notes

- ↑ In this respect, they share certain similarities with the medieval European understanding of fairies)

- ↑ For some examples of the tengu in Japanese art (over and above those included in this article, see Stephen Addiss (ed.), Japanese Ghosts & Demons: art of the supernatural, (New York: G. Braziller, Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1985). ISBN 0807611255.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 61. The specific avian species that they appear to have derived from is the tobi or tonbi (鳶), the Japanese black-eared kite (Milvus migrans lineatus).

- ↑ Mark Schumacher, "Tengu", A-Z Dictionary of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ↑ Fister p. 105. See images from this scroll here and here.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 55-57.

- ↑ Fister, p. 103. For images of the yamabushi's costume look here.

- ↑ Nakar, 61. Indeed, many early images of Europeans (especially of the early Portuguese traders who visited Japan's shores) depict them with the characteristic phallic noses of the tengu.

- ↑ For an extended discussion of this class of mystical artifacts, please see U. A. Casal's "The Lore of the Japanese Fan," Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 16 (1/2) (April 1960), pp. 53-117. He notes that the emblem of the Tengu King is "a feather-fan of flaming outline" (58 ff. 5).

- ↑ Mizuki 2001, p. 122.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Shinto:Sarutahiko

- ↑ Moriarty p. 109. See also: Japanese language blog post on tengu and Sarutahiko.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 27-30.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 34-35.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 87-90.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 43-44; Mizuki, Mujara 4, p.7.

- ↑ Mills describes one case where a tengu disguises itself as Amida Buddha, 294.

- ↑ One such tale is summarized in Blacker (1963), where the monk (who is occupied in transcribing the Lotus Sutra) is kidnapped and taunted with foreign (and no doubt malignant) wine and fish, 79. For a more general (and thorough) introduction to the medieval tales of spirit abduction (not all of which are directed at religious figures, please consult the entirety of Blacker's 1967 article.

- ↑ Indeed, any "non-passive" female sexuality was seen (in patriarchal Japanese society) as being somehow dangerous and alien. This leads to an entire genre of literature concerning women possessed by the spirit of the tengu, who then attempt to mislead pious men using their physical assets. See Tonomura, 147.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 38-43.

- ↑ Wakabayashi, 481-482, 491-493.

- ↑ See Wakabayashi, 491-492 and passim, for a description of this process.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 45-47. This tengu-ghost eventually appeared and admitted to riding on the emperor's back with his wings clasped over the man's eyes.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 48-49.

- ↑ Blacker (1967), 116.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 55-57.

- ↑ Mizuki 2001.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 51-53.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 71.

- ↑ Mizuki 2001.

- ↑ Hansen, 354.

- ↑ de Visser, p. 82; most kanji and some name corrections retrieved from here.

- ↑ Mizuki 2001

- ↑ de Visser, p. 84; Mizuki 2003, p. 70. The term konoha-tengu is often mentioned in English texts as a synonym for daitengu, but this appears to be a widely-repeated mistake which is not corroborated by Japanese-language sources.

- ↑ Mizuki 2001

- ↑ Mizuki, Mujara 4, p. 94

- ↑ Mizuki, Mujara 1, p. 38; Kaii*Yōkai Denshō Database: Kawatengu

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 58-60.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 72-76.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 76-79. The okoze fish is known to science as Anema inerme, the mottled stargazer.

- ↑ Folklore texts cited in the Kaii*Yōkai Denshō Database:

- ↑ de Visser (Fox and Badger) p. 107–109. See also: Encyclopedia of Shinto: Izuna Gongen and Encyclopedia of Shinto: Akiha Shinkō, and Saijoji, a.k.a. Doryo-son.

- ↑ Seki p. 170. Online version here.

- ↑ Seki p. 128-129. Online version here. Oni often take the place of the tengu in this story.

- ↑ Seki p. 171. A version of this story has been popularized in English as "The Badger and the Magic Fan".(ISBN 0-3992-1945-5)

- ↑ Seki p. 172. Online version here.

- ↑ Seki p. 54. This story often involves other mountain spirits, such as the yama-uba. A version specifically involving a tengu is recorded in Japanese here.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 67.

- ↑ de Visser, pp. 47-48.

- ↑ Outlined in Japanese here. For another example see the picture scroll Tengu no Dairi here, in which the tengu of Mount Kurama is working with a Buddha (who was once Yoshitsune's father) to overthrow the Taira clan. This indicates that the tengu is now involved in a righteous cause rather than an act of wickedness.

- ↑ de Visser, p. 79.

- ↑ Mizuki 2001

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary Sources

- Mizuki, Shigeru (2001). Mizuki Shigeru No Nihon Yōkai Meguri. Japan: JTB, pp. 122-123. ISBN 4-5330-3956-1.

- Mizuki, Shigeru (2003). Mujara 1: Kantō, Hokkaidō, Okinawa-hen. Japan: Soft Garage. ISBN 4-8613-3004-1.

- Mizuki, Shigeru (2003). Mujara 2: Chūbu-hen. Japan: Soft Garage. ISBN 4-8613-3005-X.

- Mizuki, Shigeru (2004). Mujara 4: Chūgoku/Shikoku-hen. Japan: Soft Garage. ISBN 4-8613-3016-5.

Supplementary Sources

- Blacker, Carmen (1963). "The Divine Boy in Japanese Buddhism". Asian Folklore Studies 22: pp. 77-88.

- Blacker, Carmen (1967). "Supernatural Abductions in Japanese Folklore". Asian Folklore Studies 26 (2): pp. 111-147.

- de Visser, M. W. (1908). "The Fox and the Badger in Japanese Folklore". Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 36 (3): pp. 107-116.

- de Visser, M. W. (1908). "The Tengu". Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 34 (2): pp. 25-99.

- Fister, Pat (1985). "Tengu, the Mountain Goblin", in Stephen Addiss: Japanese Ghosts and Demons. New York: George Braziller, Inc, pp. 103-112. ISBN 0-8076-1126-3.

- Hansen, Wilburn (2006). "The Medium is the Message: Hirata Atsutane's Ethnography of the World Beyond". History of Religions 45: pp. 337-372.

- Mills, D. E. (1972). "Medieval Japanese Tales: Part I". Folklore 83 (4): pp. 287-301.

- Moriarty, Elizabeth (1972). "The Communitarian Aspect of Shinto Matsuri". Asian Folklore Studies 31 (2): pp. 91-140.

- Nakar, Eldad (2003). "Nosing Around: Visual representation of the Other in Japanese society". Anthropological Forum 13 (1): pp. 49-66.

- Seki, Keigo (1966). "Types of Japanese Folktales". Asian Folklore Studies 25: pp. 1-220.

- Tonomura, Hitoro (1994). "Black Hair and Red Trousers: Gendering the Flesh in Medieval Japan". The American Historical Review 99 (1): pp. 129-154.

- Wakabayashi, Haruko (Winter 1999). "From Conqueror of Evil to Devil King: Ryogen and Notions of Ma in Medieval Japanese Buddhism". Monumenta Nipponica 54 (4): pp. 481-507.

External links

- The Tengu by M. W. de Visser, courtesy of Google Books.

- Tengu: the Slayer of Vanity

- Tengu: The Legendary Mountain Goblins of Japan

- Metropolis - Big in Japan: Tengu

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.