Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Samuel Adams" - New World

Laura Brooks (talk | contribs) (import, credit and version number) |

Laura Brooks (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

|religion= Congregational | |religion= Congregational | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

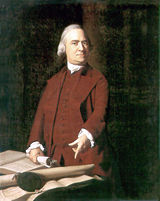

'''Samuel Adams''' ([[September 27]], [[1722]] – [[October 2]], [[1803]]) was the chief Massachusetts leader of the Patriot cause leading to the American Revolution. Organizer of protests including the [[Boston Tea Party]], he was most influential as a writer and theorist who articulated the principles of [[republicanism]] that shaped the American political culture. | '''Samuel Adams''' ([[September 27]], [[1722]] – [[October 2]], [[1803]]) was the chief Massachusetts leader of the Patriot cause leading to the American Revolution. Organizer of protests including the [[Boston Tea Party]], he was most influential as a writer and theorist who articulated the principles of [[republicanism]] that shaped the American political culture. | ||

| Line 99: | Line 98: | ||

"And that the said Constitution be never construed to authorize Congress to infringe the just liberty of the press, or the rights of conscience; or to prevent the people of the United States, who are peaceable citizens, from keeping their own arms; or to raise standing armies, unless necessary for the defense of the United States, or of some one or more of them; or to prevent the people from petitioning, in a peaceable and orderly manner, the federal legislature, for a redress of grievances; or to subject the people to unreasonable searches and seizures of their persons, papers or possessions" —Samuel Adams, Debates of the Massachusetts Convention of 1788{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | "And that the said Constitution be never construed to authorize Congress to infringe the just liberty of the press, or the rights of conscience; or to prevent the people of the United States, who are peaceable citizens, from keeping their own arms; or to raise standing armies, unless necessary for the defense of the United States, or of some one or more of them; or to prevent the people from petitioning, in a peaceable and orderly manner, the federal legislature, for a redress of grievances; or to subject the people to unreasonable searches and seizures of their persons, papers or possessions" —Samuel Adams, Debates of the Massachusetts Convention of 1788{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Primary sources== | ==Primary sources== | ||

| Line 122: | Line 119: | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | ||

*[http://quotes.liberty-tree.ca/quotes_by/samuel+adams Samuel Adams quotes at Liberty-Tree.ca] | *[http://quotes.liberty-tree.ca/quotes_by/samuel+adams Samuel Adams quotes at Liberty-Tree.ca] | ||

*{{gutenberg author | id=Samuel_Adams | name=Samuel Adams}} | *{{gutenberg author | id=Samuel_Adams | name=Samuel Adams}} | ||

| Line 133: | Line 130: | ||

{{start box}} | {{start box}} | ||

| − | |||

{{succession box | {{succession box | ||

| title=[[Governor of Massachusetts|Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts]] | | title=[[Governor of Massachusetts|Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts]] | ||

| Line 145: | Line 141: | ||

| years=[[October 8]], [[1793]] — [[June 2]], [[1797]]<br><small>(acting, 1793-1794)}} | | years=[[October 8]], [[1793]] — [[June 2]], [[1797]]<br><small>(acting, 1793-1794)}} | ||

{{end box}} | {{end box}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Persondata | {{Persondata | ||

Revision as of 00:33, 26 February 2007

| Samuel Adams | |

| |

4th Governor of Massachusetts

| |

| In office October 8, 1793 – June 2 1797 | |

| Lieutenant(s) | Moses Gill |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | John Hancock |

| Succeeded by | Increase Sumner |

| Born | September 27, 1722 Boston, Massachusetts |

| Died | October 2, 1803 Boston, Massachusetts |

| Political party | None |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Checkley, Elizabeth Wells |

| Religion | Congregational |

Samuel Adams (September 27, 1722 – October 2, 1803) was the chief Massachusetts leader of the Patriot cause leading to the American Revolution. Organizer of protests including the Boston Tea Party, he was most influential as a writer and theorist who articulated the principles of republicanism that shaped the American political culture.

Early life

Born to Bostonian parents, Mary Fifield and Samuel Adams, Sr. on September 27, 1722, Samuel was their tenth child. President John Adams was one of his cousins. Adams was a baptized member of Old South Church in Boston, and from the tower of the congregation's Meeting House made the loud war whoops signaling the beginning of the Boston Tea Party.

Adams attended school at Boston Latin School. At Harvard College he received a bachelor's degree in 1740 and a master's degree in 1743. Prophetically, the subject of his master's thesis was "Whether it be lawful to resist the supreme magistrate if the commonwealth cannot otherwise be preserved." After graduation Adams went to work in the office of a leading Boston merchant; it lasted no more than a few months. The exasperated man fired Adams saying "he thought he was training a businessman, not a politician."[1] After that, Adams' father gave him £1,000 to go into business for himself. Adams promptly loaned the money to a friend, who just as promptly lost it. In 1748, with the death of his father, and mother not long afterwards, Adams not only inherited the family brewery but a sizable estate as well, which included a home on Purchase Street. Within ten years, he had spent and mismanaged most of it to the point where creditors even attempted to seize his home.[2] By 1760, Adams was bankrupt and making by as a local tax collector; less than a year afterwards his accounts were £8,000 in arrears. "Making a virtue of necessity, Sam gloried in his poverty and compared himself to one of the 'Old Romans' who despised money and devoted themselves to their country's welfare."[3]

Turning his attention to politics Adams wrote political essays to the Independent Advertiser newspaper and joined a political club, the "Whipping Post Club," as well as Boston's South End Caucus, which was a powerful force in the selection of candidates for elective office. He served as tax collector of Boston from 1756 through 1764, and used non-collection of taxes as a political bargaining chip. By 1765, he was a leader in Boston's town meetings, drafting protests against the Stamp Act that protested British efforts to tax the colonists and called for a spirited defense of Americans' "invaluable Rights & Liberties." Over the next decade he became an increasingly dominant leader of the town meeting. He repeatedly insisted on the "inherent and unalienable rights" of the people,[4] a theme that became a core element of republicanism.

While a member of the legislature, Adams served as clerk of the house, in which capacity he was responsible for drafting written protests of various British governmental acts during his tenure, which continued to 1774. Notable among these was a circular letter he drafted as a response to the 1767 Townshend Acts, distributed among the other twelve colonies in a bid to achieve a united front of resistance to these acts. The failure of the legislature to rescind the contents of this letter at the express demand of King George III was one of the main factors resulting in the stationing of troops in Boston beginning in 1768.

This British troop presence in Boston, aggravated by protest activities such as Adams' formation of the Non-Importation Association, led to the Boston Massacre (a term coined by Adams) two years later. After the incident Adams chaired a town meeting which formed a petition, presented to acting governor Thomas Hutchinson, demanding the removal of two British regiments from Boston proper. Hutchinson at first claimed no responsibility for the matter, owing to his temporary status as governor, but stated he would be willing to move one regiment; the meeting was re-convened and Adams successfully urged the crowd of over 5,000 present to stand firm on the terms: "Both regiments or none!" Fearing open warfare, Hutchinson had both regiments removed to Castle William, an old fort on an island in Boston Harbor. These regiments would thereafter be known in the British Parliament as "The Sam Adams Regiments."

In 1772, after a British declaration that judges should be paid by the Crown rather than by the colonial legislatures, a demand from the people of Boston for a special session of the legislature to reconsider this matter was refused by Hutchinson. It was at this point Adams devised a system of Committees of Correspondence which was a committee that recorded the British activities, where the towns of Massachusetts would consult with each other concerning political matters via messages. Such a scheme was still technically legal under British law, but led to a de facto colonial legislative body. This system was adopted by each of the Thirteen Colonies, creating the Continental Congress.

Boston Tea Party

Samuel Adams is best remembered for helping organize the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773, in response to the Tea Act — a tax law passed in London that allowed the British East India Company to land tea free from the tax that had been imposed on it earlier. The angry reaction from all the colonies was to expedite the opening of a Continental Congress, and when the Massachusetts legislature met in Salem on June 17, 1774, Adams locked the doors and made a motion for the formation of a colonial delegation to attend the Congress. A loyalist member, faking illness, was excused from the assembly and immediately went to the governor, who issued a writ for the legislature's dissolution; however, when the legislator returned to find a locked door, he could do nothing.

Adams was one of the major proponents of the Suffolk Resolves, drafted in response to the Intolerable Acts, and adopted in September 1774. Whose "spirited" resolves called for disobedience to the Coercive Acts, endorsed military preparations for defense, and called for the meeting of an extralegal provincial congress. Adams opposed a compromise offered by Joseph Galloway and advocated boycotts of British imports through the continental associations.

Continental Congress

In September 1774 Adams retired from the legislature and was a delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. He was one of the first and loudest voices for independence. (Notably, only he and John Hancock were exempted from the general amnesty offered by Thomas Gage to Massachusetts rebels in 1775.) He was a workhorse member of the Second Continental Congress, serving on numerous committees, notably the Board of War, from May 1775 until 1781.

The climax of his career came when he signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. After that Adams, wary of a strong central government, was instrumental in the development and adoption of the loose government embodied in the Articles of Confederation, to which he was also a signatory in 1777. Like others in his party, Adams had both a suspicion and dislike of both General George Washington, declaring the army had "too many idle, cowardly...drunken generals",[6]

and the American army itself, often saying, "The sins of America will be punished by a standing army."[7] He continued serving in the Congress until 1781, when he was elected to the state senate of Massachusetts. He served in that body until 1788, becoming its president.

State politics

At the time of the drafting of the United States Constitution, Adams was considered an anti-federalist, but more moderate than others of that political stripe. His contemporaries nicknamed him "the last Puritan" for his views; in 1788 he would write in his diary regarding the federalist and anti-federalist factions, "Neither Interest, I fear, display that Sobriety of Manners, Temperance, or Frugality—among other manly Virtues—which once were the Glory and Strength of our Christian Sparta on the Bay...". He finally came in on the side of ratification, with the stipulation that a bill of rights be added. Additionally, Adams was a member of the conventions that drafted the first Massachusetts state constitution in 1779, and the second one in 1788.

He stood unsuccessfully for election to the House of Representatives for the first Congress, but was elected Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts, serving from 1789–94. He was elected as governor in 1793 to succeed John Hancock, and served to 1797, afterwards retiring to his home in Boston.

Later life

In old age, Samuel suffered from symptoms akin to those of Cerebral palsy or Parkinson's disease, so Samuel's daughter Hannah had to sign his name for him.

In addition to his daughter Hannah, Adams had a son named Samuel Adams, Jr., by his first wife, Elizabeth Checkley (1725-1757), whom he married in 1749. She died three days after the birth of their last child, a stillborn.

He and his second wife, Elizabeth Wells, whom he married in 1764, did not have any children.

His son, Samuel Adams, Jr., studied medicine under Doctor Joseph Warren, fellow patriot and friend to both Adams and his second cousin John Adams. Samuel Adams, Jr. held an appointment as surgeon in Washington's army. He died in 1788. His government claims provided enough for Adams and his wife to live on in their old age.

It was rumored that he and his wife's slave Surry were involved in a love affair, which Adams insisted was not true. Yet some of his letters were burned by Surry and Surry liked to recount tales of her master's friendly laugh and wholesome heart. She also spread rumors of rages, which may be founded on fact.

Adams died at the age of 81 in 1803 and was interred at the Granary Burying Ground in Boston. Owing to his occupation as a brewer, today a popular brand of Boston beer bears his name: Samuel Adams.

Legacy

Adams has been regarded as a controversial figure in American history. In one viewpoint, he is seen as a pre-Revolution political visionary and leader, noted as the "Patriarch of Liberty" by Thomas Jefferson and the "Father of the American Revolution" by the people of his time.[8] After Samuel's death, his cousin John stated:

| “ | Without the character of Samuel Adams, the true history of the American Revolution can never be written. For fifty years his pen, his tongue, his activity, were constantly exerted for his country without fee or reward.[9] | ” |

Adams is associated with laying down the groundwork needed towards solidifying the thirteen colonies. In the pre-war times, the patriotic Adams emerged as a leader and a strategic and influential political writer.[10] From 1764, Adams struggled to persuade his fellow colonists to move away from their allegiance to King George III and rise against the British control. He was the first leader to proclaim the Parliament of England had no legal authority to preside over America. Adams pioneered strategies of using the media to spread his revolutionary goals and ideas. In his monumental work, History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, historian and politician George Bancroft said, "No one had equal influence over the popular mind"[11] in the movement leading up to the war. American philosopher and historian John Fiske ranked Adams second only to George Washington in terms of importance to the founding of the nation.[12]

Still, Adams has been overlooked by many biographers and historians because he did not have a major role in national politics during the time after the United States had become an independent nation. More crucial examinations of his record as a leader has produced works depicting Adams in a negative light. In his 1923 biographical work, Samuel Adams - Promoter of the American Revolution: A Study of Psychology and Politics, author Ralph V. Harlow portrays Adams as a zealot and a propagandist for the American independence movement.[13] A similar view is also connoted in John C. Miller's 1936 biography, Samuel Adams: A Pioneer in Propaganda.[14] More recent works have shown Adams as a propagandist who used the independence movement to further his own political ambitions, as stated in Russell Kirk's 1974 book The Roots of American Order in which Kirk labels Adams as a "well-born demagogue".[15]

In her 1980 biographical work, The Old Revolutionaries: Political Lives in the Age of Samuel Adams, historian Pauline Maier argues that Adams was not the "grand incendiary" or firebrand of Revolution and was not a mob leader. She says that he took a moderate position based firmly on the English revolutionary tradition that imposed strict constraints on resistance to authority. That belief justified force only against threats to the constitutional rights so grave that the "body of the people" recognized the danger and after all the peaceful means of redress had failed. Within that revolutionary tradition, resistance was essentially conservative, intended to preserve what Adams described in 1748 as "the true object" of patriotic loyalty, "a good legal constitution, which...condemns every instance of oppression and lawless power." It had nothing in common with sedition or rebellion, which Adams, like earlier English writers, charged to officials who sought "illegal power".

Famous quotations

"If ye love wealth greater than liberty, the tranquility of servitude greater than the animating contest for freedom, go home from us in peace. We seek not your counsel, nor your arms. Crouch down and lick the hand that feeds you; May your chains set lightly upon you, and may posterity forget that ye were our countrymen." —Speech delivered at the State House in Philadelphia, “to a very numerous audience,” on August 1, 1776. [1]

"In monarchy the crime of treason may admit of being pardoned or lightly punished, but the man who dares rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death." —Commenting on Shays Rebellion [2]

"If ever time should come, when vain and aspiring men shall possess the highest seats in Government, our country will stand in need of its experienced patriots to prevent its ruin." Samuel Adams, attributed [3]

“We have this day restored the Sovereign to Whom all men ought to be obedient. He reigns in heaven and from the rising to the setting of the sun, let His kingdom come.” — Samuel Adams, attributed, upon signing the Declaration of Independence[citation needed]

"Driven from every other corner of the earth, freedom of thought and the right of private judgment in matters of conscience, direct their course to this happy country as their last asylum." —Samuel Adams, Speech, 1 August 1776[citation needed]

"And that the said Constitution be never construed to authorize Congress to infringe the just liberty of the press, or the rights of conscience; or to prevent the people of the United States, who are peaceable citizens, from keeping their own arms; or to raise standing armies, unless necessary for the defense of the United States, or of some one or more of them; or to prevent the people from petitioning, in a peaceable and orderly manner, the federal legislature, for a redress of grievances; or to subject the people to unreasonable searches and seizures of their persons, papers or possessions" —Samuel Adams, Debates of the Massachusetts Convention of 1788[citation needed]

Primary sources

- The Writings of Samuel Adams ed. by Harry Alonzo Cushing; 1904-8, 4 vol.

- William V. Wells, The Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams: Being a Narrative of His Acts and Opinions, and of His Agency in Producing and Forwarding the American Revolution, with Extracts from His Correspondence, State Papers, and Political Essays. 3 Vol 1865

Bibliography

- John K. Alexander. Samuel Adams: America's Revolutionary Politician (2002)

- Steward Beach, Samuel Adams, The Fateful Years, 1764-1776 (1965),

- David Hackett Fischer. Paul Revere's Ride (1994)

- Dennis Brindell Fradin. Samuel Adams: The Father of American Independence (1998) for middle school audience

- James Kendall Hosmer. Samuel Adams 1885 online edition

- Benjamin H. Irvin. Sam Adams: Son of Liberty, Father of Revolution Oxford University Press, 2002. Pp. 176.

- Pauline Maier. From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776 (1992)

- Pauline Maier, The Old Revolutionaries: Political Lives in the Age of Samuel Adams (1980) chap. 1: "A New Englander as Revolutionary: Samuel Adams,” pp 3-50

- John C. Miller, Sam Adams, Pioneer in Propaganda (1936)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Fleming, Thomas (October 2005). Samuel Adams: Father of the American Revolution. New York: HarperCollins, p77. ISBN 0-06082962-1.

- ↑ Scott Cummings. The Patriotic Resource: Samuel Adams. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ↑ Fleming (2005) p. 78

- ↑ Adams, Samuel (May 1904). in Harry Alonzo Cushing: The Writings of Samuel Adams. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, vol. 1, pp25-26.

- ↑ Key to Declaration of Independence. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ↑ Miller, John C. (1936). Sam Adams, Pioneer in Propaganda. Boston: HarperCollins, p345. ISBN 0-06082962-1.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Puls, Mark (October 2006). Samuel Adams: Father of the American Revolution. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p14. ISBN 1-4039-7582-5.

- ↑ Puls (2006)

- ↑ Puls (2006), p235

- ↑ Bancroft, George (1882). History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, Vol. 3, p77.

- ↑ Hosmer, James Kendall (1888). Samuel Adams. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, p370.

- ↑ Puls (2006), p15

- ↑ Puls (2006), p16

- ↑ Puls (2006), p16

External links

- Samuel Adams quotes at Liberty-Tree.ca

- Works by Samuel Adams. Project Gutenberg

- Adams' biography at U.S. Congress website

- Official Commonwealth of Massachusetts Governor Biography

- Adams Genealogy

- Biography by Rev. Charles A. Goodrich, 1856

- Biography resources dedicated to Samuel Adams

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Adams, Samuel

| Preceded by: Benjamin Lincoln |

Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts 1789 — 1794 |

Succeeded by: Moses Gill |

| Preceded by: John Hancock (died) |

Governor of Massachusetts October 8, 1793 — June 2, 1797 (acting, 1793-1794) |

Succeeded by: Increase Sumner |

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Adams, Samuel |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | American revolutionary |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 27, 1722 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Boston, Massachusetts |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 2, 1803 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Boston, Massachusetts |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.