Saladin

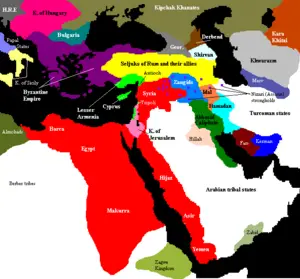

Saladin or Salah ad-Din, or Salahuddin Ayyubi (Arabic: صلاح الدين الأيوبي, Kurdish: صلاح الدین ایوبی) (so-lah-hood-din al-aye-yu-be) (c. 1138 - March 4, 1193) was a twelfth century Kurdish Muslim general and warrior from Tikrit, in present day northern Iraq. He founded the Ayyubid dynasty of Egypt, Syria, Yemen (except for the Northern Mountains), Iraq, Mecca Hejaz and Diyar Bakr. Saladin is renowned in both the Muslim and Christian worlds for leadership and military prowess, tempered by his chivalry and merciful nature during his war against the Crusaders. In relation to his Christian contemporaries, his character was exemplary, to an extent that propagated stories of his exploits back to the west, incorporating both myth and facts. Salah ad-Din is an honorific title which translates to The Righteousness of the Faith from Arabic.

Rise to power

Saladin was born in 1138 into a Kurdish [1] family in Tikrit and was sent to Damascus to finish his education. His father, Najm ad-Din Ayyub, was governor of Baalbek. For ten years Saladin lived in Damascus and studied Sunni Theology, at the court of Nur ad-Din (Nureddin). After an initial military education under the command of his uncle, Nur ad-Din's lieutenant Shirkuh, who was representing Nur ad-Din on campaigns against a faction of the Fatimid caliphate of Egypt in the 1160s, Saladin eventually succeeded the defeated faction and his uncle as vizier in 1169. There, he inherited a difficult role defending Egypt against the incursions of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, under Amalric I. His position was tenuous at first; no one expected him to last long in Egypt where there had been many changes of government in previous years due to a long line of child caliphs fought over by competing viziers. As the leader of a foreign army from Syria, he also had no control over the Shi'ite Egyptian army, which was led in the name of the now otherwise powerless caliph Al-Adid. When the caliph died, in September 1171, Saladin had the imams pronounce the name of Al-Mustadi, the Sunni and, more importantly, Abbassid caliph in Baghdad, at sermon before Friday prayers, and the weight of authority simply deposed the old line. Now Saladin ruled Egypt, but officially as the representative of Nur ad-Din, who himself conventionally recognised the Abbassid caliph. Saladin revitalized the economy of Egypt, reorganized the military forces and, following his father's advice, stayed away from any conflicts with Nur ad-Din, his formal lord, after he had become the real ruler of Egypt. He waited until Nur ad-Din's death before starting serious military actions: at first against smaller Muslim states, then directing them against the Crusaders.

With Nur ad-Din's death (1174), he assumed the title of sultan in Egypt. There he declared independence from the Seljuks, and he proved to be the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty and restored Sunnism in Egypt. He extended his territory westwards in the maghreb, and when his uncle was sent up the Nile to pacify some resistance of the former Fatimid supporters, he continued on down the Red Sea to conquer Yemen. He is also regarded as a Waliullah which means the friend of God to the Sunni Muslims.

Fighting the Crusaders

On two occasions, in 1171 and 1173, Saladin retreated from an invasion of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. These had been launched by Nur ad-Din, and Saladin hoped that the Crusader kingdom would remain intact, as a buffer state between Egypt and Syria, until Saladin could gain control of Syria as well. Nur ad-Din and Saladin were headed towards open war on these counts when Nur ad-Din died in 1174. Nur ad-Din's heir as-Salih Ismail al-Malik was a mere boy, in the hands of court eunuchs, and died in 1181.

Immediately after Nur ad-Din's death, Saladin marched on Damascus and was welcomed into the city. He reinforced his legitimacy there in the time-honoured way — by marrying Nur ad-Din's widow. Aleppo and Mosul, on the other hand, the two other largest cities that Nur ad-Din had ruled, were never taken, but Saladin managed to impose his influence and authority on them in 1176 and 1186 respectively. While he was occupied in besieging Aleppo, on May 22, 1176 the elite shadowy assassin group "Hashshashins" attempted to murder him.

While Saladin was consolidating his power in Syria, he usually left the Crusader kingdom alone, although he was generally victorious whenever he did meet the Crusaders in battle. One exception was the Battle of Montgisard on November 25, 1177. He was defeated by the combined forces of Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, Raynald of Chatillon and the Knights Templar. Only one tenth of his army made it back to Egypt.

A truce was declared between Saladin and the Crusader States in 1178. Saladin spent the subsequent year recovering from his defeat and rebuilding his army, renewing his attacks in 1179 when he defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Jacob's Ford. Crusader counter-attacks provoked further responses by Saladin. Raynald of Chatillon, in particular, harassed Muslim trading and pilgrimage routes with a fleet on the Red Sea, a water route that Saladin needed to keep open. Raynald threatened to attack the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. In retaliation, Saladin besieged Kerak, Raynald's fortress in Oultrejordain, in 1183 and 1184. Raynald responded by looting a caravan of pilgrims on the Hajj in 1185.

In July of 1187, Saladin captured the Kingdom of Jerusalem. On July 4, 1187, he faced at the Battle of Hattin the combined forces Guy of Lusignan, King consort of Jerusalem, and Raymond III of Tripoli. In the battle alone the Crusader army was largely annihilated by the motivated army of Saladin in what was a major disaster for the Crusaders and a turning point in the history of the Crusades. Saladin captured Raynald de Chatillon and was personally responsible for his execution. (According to the chronicle of Ernoul, Raynald had captured Saladin's so-called sister in a raid on a caravan, although this is not attested to in Muslim Sources. According to Muslim Sources, Saladin never had a sister, but only mentioned the term when referring to a fellow Muslim who was female.) Guy of Lusignan was also captured but his life was spared. Two days after the Battle of Hattin, Saladin ordered the execution of all prisoners of the military orders by beheading. According to Imad al-Din, Saladin watched the executions “with a glad face.” The execution of prisoners at Hattin was not the first by Saladin. On August 29 1179, he captured the castle at Bait al-Ahazon and approximately 700 prisoners were taken and executed.

Soon, Saladin had taken back almost every Crusader city. He recaptured Jerusalem on October 2, 1187, after 88 years of Crusader rule (see Siege of Jerusalem). Saladin initially was unwilling to grant terms of quarter to the occupants of Jerusalem until Balian of Ibelin threatened to kill every Muslim in the city, estimated between 3,000 to 5,000, and to destroy Islam’s holy shrines of the Dome of the Rock and the Aqsa Mosque if quarter was not given. Saladin consulted his council and these terms were accepted. Ransom was to be paid for each Frank in the city whether man, woman, or child. Saladin allowed many to leave without having the required amount for ransom for others. According to Imad al-Din, approximately 7,000 men and 8,000 women could not make their ransom and were taken into slavery.

Only Tyre held out. The city was now commanded by the formidable Conrad of Montferrat. He strengthened Tyre's defences and withstood two sieges by Saladin. In 1188, Saladin released Guy of Lusignan and returned him to his wife Queen regnant Sibylla of Jerusalem. Both rulers were allowed to seek refuge at Tyre, but were turned away by Conrad, who did not recognise Guy as King. Guy then set about besieging Acre (see Siege of Acre).

Hattin and the fall of Jerusalem prompted the Third Crusade, financed in England by a special "Saladin tithe". This Crusade took back Acre, and Saladin's army met King Richard I of England at the Battle of Arsuf on September 7, 1191 at which Saladin was defeated. Saladin's relationship with Richard was one of chivalrous mutual respect as well as military rivalry; both were celebrated in courtly romances. When Richard was wounded, Saladin offered the services of his personal physician. At Arsuf, when Richard lost his horse, Saladin sent him two replacements. Saladin also sent him fresh fruit with snow, to keep his drinks cold. Richard had suggested to Saladin that his sister could marry Saladin's brother - and Jerusalem could be their wedding gift.

The two came to an agreement over Jerusalem in the Treaty of Ramla in 1192, whereby the city would remain in Muslim hands but would be open to Christian pilgrimages; the treaty reduced the Latin Kingdom to a strip along the coast from Tyre to Jaffa.

Saladin died on March 4, 1193 at Damascus, not long after Richard's departure. When they opened Saladin's treasury they found there was not enough money to pay for his funeral; he had given most of his money away in charity[citation needed]. His tomb is in Damascus, at the Umayyad Mosque, and is a popular attraction.

Recognition

Despite his fierce struggle to the Christian incursion, Saladin achieved a great reputation in Europe as a chivalrous knight, so much so that there existed by the fourteenth century an epic poem about his exploits, and Dante included him among the virtuous pagan souls in Limbo. The noble Saladin appears in a sympathetic light in Sir Walter Scott's The Talisman (1825). Despite the Crusaders' slaughter when they originally conquered Jerusalem in 1099, Saladin granted amnesty and free passage to all common Catholics and even to the defeated Christian army, as long as they were able to pay the aforementioned ransom (the Greek Orthodox Christians were treated even better, because they often opposed the western Crusaders). An interesting view of Saladin and the world in which he lived is provided by Tariq Ali's novel The Book of Saladin (London: Verso, 1998).

Notwithstanding the differences in beliefs, the Muslim Saladin was respected by Christian lords, Richard especially. Richard once praised Saladin as a great prince, saying that he was without doubt the greatest and most powerful leader in the Islamic world[citation needed]. Saladin in turn stated that there was not a more honorable Christian lord than Richard. After the treaty, Saladin and Richard sent each other many gifts as tokens of respect, but never met face to face.

The name Salah ad-Din means "Righteousness of Faith", and through the ages Saladin has been an inspiration for Muslims in many respects. Modern Muslim rulers have sought to capitalise on the reputation of Saladin. A governorate centred around Tikrit in modern Iraq, Salah ad Din, is named after Saladin, as is Salahaddin University in Arbil.

Few structures associated with Saladin survive within modern cities. Saladin first fortified the Citadel of Cairo (1175 - 1183), which had been a domed pleasure pavilion with a fine view in more peaceful times. In Syria, even the smallest city is centred on a defensible citadel, and Saladin introduced this essential feature to Egypt.

Among the forts he built was Qalaat Al-Gindi, a mountaintop fortress and caravanserai in the Sinai. The fortress overlooks a large wadi which was the convergence of several caravan routes that linked Egypt and the Middle East. Inside the structure are a number of large vaulted rooms hewn out of rock, including the remains of shops and a water cistern. A notable archaeological site, it was investigated in 1909 by a French team under Jules Barthoux.[1]

According to The French Writer Rene Grousse:

"It is equally true that his generosity, his piety, devoid of fanaticism, that flower of liberality and courtesy which had been the model of our old chroniclers, won him no less popularity in Frankish Syria than in the lands of Islam"

Renee Grousse The Epic of the Crusades Orion Press 1970 Translated from the French by Noel Lindsay

Burial site

Saladin is buried in a mausoleum in the garden outside the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria. Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany donated a new marble sarcophagus to the mausoleum. Saladin was, however, not placed in it. Instead the mausoleum now has two sarcophagi: one empty in marble and one in wood containing the body of Saladin.

Saladin in media

- Saladin was portrayed by Bernard Kay in the 1965 Doctor Who serial The Crusade. In the same production, Julian Glover portrayed Richard the Lionheart. The script portrayed Richard far less favourably than Saladin, in accordance with the Romantic tradition established by Walter Scott's The Talisman.

- Saladin was portrayed by Ghassan Massoud in the 2005 motion picture Kingdom of Heaven. The filmmakers sought to portray a Saladin acceptable both to Western and Middle Eastern audiences, but in doing so Saladin is reduced to a solely reactive character, albeit a noble one, going to war against the Crusaders only in retribution for the horrific acts perpetrated by the Christian Templars. In one of the scenes featured in the Director's Cut, Saladin takes up arms after a discussion with a muslim leader who was distraught over the fact that the crusaders slaughtered the city of Jerusalem. Near the end of the film Orlando Bloom's character, Balian, asks him "What is Jerusalem worth?". Saladin answers "Nothing." and walks away. He then turns back and, gesturing towards himself, says "Everything" - most likely a reference to earlier in the film, where it was established that he garnered support among the reactionary (and restless) clerics by promising the return of Jerusalem to Muslim hands from the Christian occupiers.

- Saladin was portrayed by Ahmed Mazhar in the film Al Nasser Salah Ad-Din directed by Youssef Chahine. The movie portrayed Saladin as a pacifist and noble knight, borrowing a few plot elements and general tone from Walter Scott's The Talisman. There are numerous subtle and not-so-subtle allusions to Saladin as a medieval Nasser, seeking to unite a pan-Arab middle east against western incursion.

- Saladin was portrayed by Ian Keith in the 1935 film The Crusades (film), directed by Cecil B. deMille. Notable in this film adaptation is the plot element whereby Saladin captures, and falls in love with, the wife of Richard the Lionheart.

- Saladin is being portrayed in a new animated TV series, Saladin: The Animated Series, being produced in Malaysia.[2]

- In the Metal Gear Solid video game series, the antagonist "Big Boss" is nicknamed "Saladin" by the Kurdish Sniper "Wolf"

- In the Civilization IV, Saladin is one of the faction leaders you may select, his default civilization is the Arabian Empire.

Notes

- ↑ Ibn Khallikan says that Saladin's father and his family originated from Dvin, and "they were Kurds." See Vladimir Minorsky, The Prehistory of Saladin, Studies in Caucasian History, Cambridge University Press, 1957, pp. 124-132.

- ↑ Saladin: The Animated Series official site. Multimedia Development Corporation. Malaysia, 2006.

See also

- Kurdish People

- History of Arab Egypt

- Alvis Saladin, a British armoured car named after Saladin used by the British Army and others

External links

- The Real Saladin: Separating fact from fiction in the film Kingdom of Heaven

- Saladin

- Saladin: several links

- Richard and Saladin: Warriors of the Third Crusade

- De expugnatione terrae sanctae per Saladinum A European account of Saladin's conquests of the Crusader states, written a few years after his capture of Jersusalem, including an eyewitness account of the siege of Jerusalem supplied by a soldier who was wounded there. In Latin.

- Saladin: The Animated Series

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baha ad-Din, The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin, ed. D. S. Richards, Ashgate, 2002.

- Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani, Conquête de la Syrie et de la Palestine par Salâh ed-dîn, ed. Carlo Landberg, Brill, 1888.

- Stanley Lane-Poole, Saladin and the Fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Putnam, 1898.

- H. A. R. Gibb, The Life of Saladin: From the Works of Imad ad-Din and Baha ad-Din. Clarendon Press, 1973.

- M. C. Lyons and D. E. P. Jackson, Saladin: the Politics of the Holy War, Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Alan K. Bowman, Egypt After the Pharaohs, 1986.

- John Gillingham, "Richard I", Yale English Monarchs, Yale University Press, 1999.

ar:صلاح الدين الأيوبي bs:Saladin br:Saladin ca:Saladí cs:Saladin da:Saladin de:Saladin el:Σαλαντίν es:Saladino eo:Saladino eu:Saladin fa:صلاحالدین ایوبی fr:Saladin ga:Saladin gl:Saladino id:Salahuddin Ayyubi is:Saladín it:Saladino he:צלאח א-דין ku:Silhedînê Eyûbî li:Saladin mk:Саладин ms:Salahuddin Al-Ayubbi nl:Saladin ja:サラーフッディーン no:Saladin nn:Saladin pl:Saladyn pt:Saladino ro:Saladin ru:Саладин scn:Saladinu simple:Saladin sl:Saladin sr:Саладин sh:Saladin fi:Saladin sv:Saladin th:ศอลาฮุดดีน tr:Selahaddin Eyyubi uk:Саладин ur:صلاح الدین ایوبی zh:萨拉丁

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.