Reductionism

Template loop detected: Template:Split

In philosophy, reductionism is a theory that asserts that the nature of complex things is reduced to the nature of sums of simpler or more fundamental things. This can be said of objects, phenomena, explanations, theories, and meanings.

Reductionism is often understood to imply the unity of science. For example, fundamental chemistry is based on physics, fundamental biology and geology are based on chemistry, psychology is based on biology, sociology is based on psychology, and political science, anthropology, and even economics are based on sociology. The first two of these reductions are commonly accepted but the last three or four — psychology to biology and so on — are controversial. For example, aspects of evolutionary psychology and sociobiology are rejected by those who claim that complex systems are inherently irreducible or holistic. Some strong reductionists believe that the behavioral sciences should become "genuine" scientific disciplines by being based on genetic biology, and on the systematic study of culture (cf. Dawkins's concept of memes).

In his book The Blind Watchmaker, Richard Dawkins introduced the term "hierarchical reductionism" (p. 13) to describe the view that complex systems can be described with a hierarchy of organizations, each of which can only be described in terms of objects one level down in the hierarchy. He provides the example of a computer, which under hierarchical reductionism can be explained well in terms of the operation of hard drives, processors, and memory, but not on the level of AND or NOR gates, or on the even lower level of electrons in a semiconductor medium.

Varieties of reductionism

There are several generally accepted types or forms of reduction in both science and philosophy:

Ontological reductionism

Is the idea that everything that exists is made from a small number of basic substances that behave in regular ways (compare to monism). There are two forms of ontological reductionism: token ontological reductionism, and type ontological reductionism. Token ontological reductionism is the idea that every item that exists is a sum item. For perceivable items, it says that every perceivable item is a sum of items at a smaller level of complexity. Type ontological reductionism is the idea that every type of item is a sum (of typically less complex) type(s) of item(s). For perceivable types of item, it says that every perceivable type of item is a sum of types of items at a lower level of complexity. Token ontological reduction of biological things to chemical things is generally accepted. Type ontological reduction of biological things to chemical things is often rejected.

Methodological reductionism

Is the idea that developing an understanding of a complex system's constituent parts (and their interactions) is the best way to develop an understanding of the system as a whole.[1]

Methodological individualism

Protends sociological inquiry based on individual decisions.

Theoretical reductionism

Has two definitions. In the first definition it is the idea that the terms of a theory of science A referring to objects at a higher level of complexity than the objects of science B can be replaced by the terms of science B. In the second definition of theoretical reductionism the older theories or explanations are not generally replaced outright by new ones, but new theories are refinements or reductions of the old theory into more efficacious forms with greater detail and explanatory power. The older theories are supposedly absorbed into the newer ones and they can be deductively derived from the latter.

Scientific reductionism

Has been used to describe all of the above ideas as they relate to science, but is most often used to describe the idea that all phenomena can be reduced by scientific explanations. It is useful to note in addition that there are no explicit theories that reject token ontological reduction of biological items to chemical items, or that reject token ontological reduction of chemical items to physics items. Also by the middle of the 20th century the empirical results made extremely implausible the view that there are fundamental forces activated only by highly complex configurations of subatomic particles.

Set-Theoretic Reductionism

Is the idea that all of mathematics can be reduced to set theory. Throughout the history of mathematics, the idea that all of mathematics can be reduced to a single branch has been very powerful. However, most of the attempts to reduce mathematics to a single branch have been proven either incomplete or inconsistent. Most of these proofs were developed by Gottlob Frege. He then proposed his own form of reductionism, logicism, which in turn was famously disproven by Russell's Paradox. Many believe that Godel's Incompleteness Theorem proves that reductionism in mathematics is impossible (since all systems cannot be both complete and consistent at the same time), but there is still a great deal of debate on the matter.

Linguistic reductionism

Is the idea that everything can be described in a language with a limited number of core concepts, and combinations of those concepts. (See Basic English and the constructed language Toki Pona).

Greedy reductionism

Is a term coined by Daniel Dennett to condemn those forms of reductionism that try to explain too much with too little.

Eliminativism

Is sometimes regarded as a form of reductionism. Eliminativism is the idea that some objects referred to in a given theory do not exist. Accordingly, the terms of that theory are abandoned or eliminated. Eliminativism is often regarded as a form of reductionism, since the eliminated theory is at some point replaced by a theory referring to the objects that were not eliminated. For example, the theory that some diseases are caused by occupation by a demon has been eliminated. Accordingly it has been reduced by elimination to other theories about the causes of diseases.

Other typologies are also possible. For example, Richard Jones in a systematic study of reductionism in philosophy, the natural sciences, the social sciences and religion differentiates five types: substantive, structural (causal), theoretical, conceptual (descriptive), and methodological. He critiicizes reductionism and advocates the importance of emergence. John Dupre also advocates antireductionism.

The denial of reductionist ideas is holism or emergentism: the idea that things can have properties as a whole that are not explainable from the sum of their parts. The principle of holism was concisely summarized by Aristotle in the Metaphysics: "The whole is more than the sum of its parts". Phenomena such as emergence and work within the field of complex systems theory are also considered to bring forth possible objections to some forms of reductionism. It's worth noticing that they don't object to token ontological reduction of biology to chemistry, nor to token ontological reduction of chemistry to physics. They would only be possible objections to other forms of reduction.

Outside the field of strictly philosophical discourse and outside the fields of biology, chemistry and physics, the best known denial of reductionisms of whatever kind is religious belief, which, in most of its forms, assigns supernatural original causes to phenomena. In this approach, even if a given system operates by strictly reductionistic causes-and-effects, its "true" genesis and placement within larger (and typically unknown) systems is bound up with an intelligence or "consciousness" beyond normal human perception. It is worth asking how religious systems regard token biological reduction of biological items to chemical items and chemical items to physics items.

History

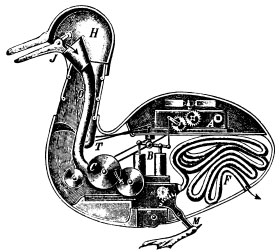

The idea of reductionism was introduced by Descartes in Part V of his Discourses (1637). Descartes argued the world was like a machine, its pieces like clockwork mechanisms, and that the machine could be understood by taking its pieces apart, studying them, and then putting them back together to see the larger picture. Descartes was a full mechanist, but only because he did not accept the conservation of direction of motions of small things in a machine, including an organic machine. Newton's theory required such conservation for inorganic things at least. When such conservation was accepted for organisms as well as inorganic objects by the middle of the 20th century, no organic mechanism could easily, if at all, be a Cartesian mechanism.

See also

- holism

- emergentism

- scientific reductionism

- theology

- Aristotle

- Philosophy of Mind

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dawkins, R. (1976) The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press; 2nd edition, December 1989 ISBN 0-19-217773-7.

- Descartes (1637) Discourses Part V

- Dupre, J. (1993) The Disorder of Things. Harvard University Press.

- Jones, R. (2000) Reductionism: Analysis and the Fullness of Reality. Bucknell University Press.

- Nagel, E. (1961) The Structure of Science. New York.

- Ruse, M. (1988) Philosophy of Biology. Albany, NY.

- Dennett, Daniel. (1995) Darwin's Dangerous Idea. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-82471-X.

- Alexander Rosenberg (2006) Darwinian Reductionism or How to Stop Worrying and Love Molecular Biology. University of Chicago Press.

External links

- John Dupré: The Disunity of Science, an interview at the Galilean Library covering criticisms of reductionism.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Phisics Holism, Stanford University.