Prehistoric Korea

- This article is about the prehistory of the Korean Peninsula, from circa 500,000 BC through 300 BC. See History of Korea, History of North Korea and History of South Korea for more contemporary accounts of the Korean past. See also Names of Korea.

The Prehistory of the Korean Peninsula is the era for which documentary evidence does not exist and that constitutes the greatest segment of the Korean past. It is the major object of study in the disciplines of archaeology, geology, and palaeontology.

Geological prehistory

Geological prehistory is the most ancient part of Korea's past. The oldest rocks in Korea date to the Precambrian. The Yeoncheon System corresponds to the Precambrian and is distributed around Seoul extending out to Yeoncheon-gun in a northeasterly direction. It is divided into upper and lower parts and is composed of biotite-quartz-feldspar schist, marble, lime-silicate, quartzite, graphite schist, mica-quartz-feldspar schist, mica schist, quartzite, augen gneiss, and garnet-bearing granitic gneiss. The Korean Peninsula had an active geological prehistory through the Mesozoic, when many mountain ranges were formed, and slowly became more stable in the Cenozoic. Major Mesozoic formations include the Gyeongsang Supergroup, a series of geological episodes in which biotite granites, shales, sandstones, conglomerates andesite, basalt, rhyolite, and tuff that were laid down over most of present-day Gyeongsang-do Province.

The remainder of this article describes the human prehistory of the Korean Peninsula.

Periods in Korean human prehistory

Palaeolithic

The origins of this period are an open question but the antiquity of Hominid occupation in Korea may date to as early as c. 500,000 BC. Yi and Clark are somewhat skeptical of dating the earliest occupation to the Lower Palaeolithic (Yi and Clark 1986). The Palaeolithic ends when pottery production begins c. 8000 BC.

The earliest radiocarbon dates for this period indicate the antiquity of occupation on the Korean peninsula is between 40,000 and 30,000 B.P. (Bae 2002). If Hominid antiquity extends as far as 500,000 BC, it would seem to imply that Homo erectus could have been present in the Korean peninsula.

Jeulmun Pottery Period

The earliest known Korean pottery dates back to c. 8000 BC or before. This pottery is known as Yungimun Pottery (ko:융기문토기) is found in much of the peninsula. Some examples of Yungimun-era sites are Gosan-ri in Jeju-do and Ubong-ri in Greater Ulsan. Jeulmun or Comb-pattern Pottery (즐문토기) is found after 7000 BC, and pottery with comb-patterns over the whole vessel is found concentrated at sites in west–central Korea between 3500–2000 BC, a time when a number of settlements such as Amsa-dong and Chitam-ni existed. Jeulmun pottery bears basic design and form similarities to that of the Russian Maritime Province, Mongolia, and the Amur and Sungari River basins of Manchuria.

The people of the Jeulmun practiced a broad spectrum economy of hunting, gathering, foraging, and small-scale cultivation of wild plants. It was during the Jeulmun that the cultivation of millet and rice was introduced to the Korean peninsula from the Asian continent.

Mumun Pottery Period

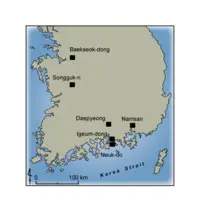

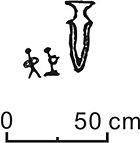

Agricultural societies and the earliest forms of social-political complexity emerged in the Mumun Pottery Period (c. 1500–300 BC). People in southern Korea adopted intensive dry-field and paddy-field agriculture with a multitude of crops in the Early Mumun Period (1500–850 BC). The first societies led by big-men or chiefs emerged in the Middle Mumun (850–550 BC), and the first ostentatious elite burials can be traced to the Late Mumun (c. 550–300 BC). Bronze production began in the Middle Mumun and became increasingly important in Mumun ceremonial and political society after 700 BC. The Mumun is the first time that villages rose, became large, and then fell: some important examples include Songgung-ni, Daepyeong, and Igeum-dong. The increasing presence of long-distance exchange, an increase in local conflicts, and the introduction of bronze and iron metallurgy are trends denoting the end of the Mumun around 300 BC.

The period that begins after 300 BC can be described as a 'protohistoric' period, a time when some documentary sources seem to describe socieites in the Korean peninsula. The historical polities described in ancient texts such as the Samguk Sagi are an example. The Korean Protohistoric lasts until AD 300/400 when the early historic Korean Three Kingdoms formed as archaeologically recognizable state societies.

Perspectives on Korean prehistory from the discipline of History

Ancient texts such as the Samguk Sagi, Samguk Yusa, Book of Later Han or Hou Han Shou, and others have sometimes been used to interpret segments of Korean prehistory. The most well-known version of the founding story that relates the origins of the Korean ethnicity explains that Dangun came to the earth in 2333 B.C.E. A significant amount of historical inquiry in the 20th century was devoted to the interpretation of the accounts of Gojoseon (2333–108 BC), Gija Joseon (323–194 BC), Wiman Joseon (194–108 BC) and others mentioned in historical texts.

A great deal of archaeological activity has taken place in both North and South Korea since the mid-1950s, but no direct archaeological evidence has yet been discovered of these entities from the discipline of Korean history. It is difficult to even link indirect archaeological evidence with Gojoseon or the others, so tenuous are the current links between the archaeological data and historical texts.

However, in the 1990s North Korean media reports claimed that Dangun's tomb was discovered and partially excavated. Archaeologists and mainstream historians outside of North Korea are generally skeptical of the dating methods, since the government has not permitted independent access and testing. Additionally, the claims made about the partial excavation of a large-scale burial dating to before 2000 BC are even more unusual given that other contemporary archaeological sites consist of small isolated settlements and subsistence-related sites such as shellmiddens.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ahn, Jae-ho.

- 2000 Hanguk Nonggyeongsahoe-ui Seongnip [The Formation of Agricultural Society in Korea]. Hanguk Kogo-Hakbo [Journal of the Korean Archaeological Society] 43: 41–66. ISSN 1015-373X

- Bae, Kidong

- 2002 Radiocarbon Dates from Palaeolithic Sites in Korea. Radiocarbon 44(2): 473–476.

- Bale, Martin T.

- 2001 Archaeology of Early Agriculture in Korea: An Update on Recent Developments. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 21(5): 77–84. ISSN 0156-1316

- Bale, Martin T. and Min-jung Ko

- 2006 Craft Production and Social Change in Mumun Period Korea. Asian Perspectives 45(2): 159–187.

- Choe, C.P. and Martin T. Bale

- 2002 Current Perspectives on Settlement, Subsistence, and Cultivation in Prehistoric Korea. Arctic Anthropology 39(1–2): 95–121. ISSN 0066-6939

- Crawford, Gary W. and Gyoung–Ah Lee

- 2003 Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula. Antiquity 77(295): 87–95.

- Im, Hyo-jae

- 2000 Hanguk Sinseokgi Munhwa [Neolithic Culture in Korea]. Jibmundang, Seoul. ISBN 89-303-0257-2

- Kim, Jangsuk

- 2003 Land-use Conflict and the Rate of Transition to Agricultural Economy: A Comparative Study of Southern Scandinavia and Central-western Korea. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 10(3): 277–321.

- Kim, Seung Og

- 1996 Political Competition and Social Transformation: The Development of Residence, Residential Ward, and Community in Prehistoric Taegongni of Southwestern Korea. PhD dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Proquest, Ann Arbor.

- Kuzmin, Yaroslav V.

- 2006 Chronology of the Earliest Pottery in East Asia: Progress and Pitfalls. Antiquity 80: 362–371.

- Lee, June-Jeong

- 2001 From Shellfish Gathering to Agriculture in Prehistoric Korea: The Chulmun to Mumun Transition. PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madision. Proquest, Ann Arbor.

- Nelson, Sarah M.

- 1993 The Archaeology of Korea. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-40783-4

- Nelson, Sarah M

- 1999 Megalithic Monuments and the Introduction of Rice into Korea. In The Prehistory of Food: Appetites for Change, edited by C. Gosden and J. Hather, pp. 147–165. Routledge, London.

- Rhee, S. N. and M. L. Choi

- 1992 Emergence of Complex Society in Prehistoric Korea. Journal of World Prehistory 6: 51–95.

- Yi, Seon-bok and G.A. Clark

- 1983 Observations on the Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Northeast Asia. Current Anthropology 24(2): 181–202.

See also

- List of archaeological periods (Korea)

- Bangudae Petroglyphs