Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Pavel Josef Šafařík" - New World

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

=== Bohemia (1833 - 1861)=== | === Bohemia (1833 - 1861)=== | ||

| − | + | While in Novi Sad, Šafařík maintained contact with Czech and Slovak revivalists, especially with Kollár, but isolation from his fellow Czech and Slovak revivalists was very hard to bear. Only in 1833 was he able to move to Prague, after an unsuccessful search for a teacher or librarian tenure in [[Russia]]. It was Kollár, aided by his influential friends in Prague, who promised to finance his sojourn in Prague, which was to become his adoptive homeland until his death. He literally depended, especially in the 1840s, on 380 [[gulden]]s annually, a stipend from his Czech friends under the condition that, as Palacký explicitly said, "from now on, anything you write, you will write it in the Czech language only". | |

| − | + | Šafárik supported his meager income as an editor of the Světozor journal until poverty compelled him to accept the job of a [[Censorship|censor]] of Czech publications in 1837, which he abandoned ten years later. For four years he was first editor, then director of the journal ''Časopis Českého musea''. Since 1841 he was a custodian of the Prague University Library. | |

| − | + | In Prague, he published most of his works, especially his greatest Slovanské starožitnosti. He also edited the first volume of Vybor (selected works by early Czech writers), which came out under the auspices of the [[Prague literary society]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In | + | === Šafárik’s Stance on Slovak Language and Slovakia=== |

| + | In "Hlasowé o potřebě jednoty spisowného jazyka pro Čechy, Morawany a Slowáky" [Voices on the Necessity of a United Literal Language for the Czechs, Moravians and Slovaks] published by Kollár in 1846, Šafárik moderately criticized [[Ľudovít Štúr]]'s introduction of a new [[History of the Slovak language|Slovak standard language]] from 1843. Štúr namely replaced the previously employed Lutheran vernacular, which was closer to the Czech language. Slovak Catholics used a different vernacular. | ||

| − | + | Contrary to most of his Czech friends, Šafárik considered the Slovaks a separate nation from the Czechs, and he said so in his Geschichte der slawischen Sprache . . . and in Slovanský národopis. However, he did not advocate a separate Slovak language, only the Slovak vernacular of it as the language of Slovak literature. | |

During the [[Revolution of 1848]] he was mainly collecting material for books on the oldest Slavic history (see Works). In [[1848]] he was made head of the University Library of Prague and an extraordinary professor of Slavonic philology in the [[University of Prague]], but resigned to the latter in 1849 and remained head of the university library only. The reason for this resignation was that during the Revolution of 1848-49 he participated at the [[Slavic Congress]] in Prague (June 1848) and thus became suspicious for [[Austria]]n authorities. During the [[Political absolutism|absolutistic]] period following the defeat of the revolution, he lived a secluded life and studied especially older [[Czech literature]] and [[Old Church Slavonic]] texts and culture. | During the [[Revolution of 1848]] he was mainly collecting material for books on the oldest Slavic history (see Works). In [[1848]] he was made head of the University Library of Prague and an extraordinary professor of Slavonic philology in the [[University of Prague]], but resigned to the latter in 1849 and remained head of the university library only. The reason for this resignation was that during the Revolution of 1848-49 he participated at the [[Slavic Congress]] in Prague (June 1848) and thus became suspicious for [[Austria]]n authorities. During the [[Political absolutism|absolutistic]] period following the defeat of the revolution, he lived a secluded life and studied especially older [[Czech literature]] and [[Old Church Slavonic]] texts and culture. | ||

In 1856/57, as a result of persecution anxieties, overwork, and ill health, he became physically and mentally insane and burned most of his correspondence with important personalities (e. g. with Ján Kollár). In May 1860, his [[clinical depression|depression]]s made him to jump into the [[Vltava]] river, but he was saved. This event produced considerable sensation among the general public. In early October 1860 he asked for retirement from his post as University Library head. The Austrian [[emperor]] himself enabled him this in a letter written by his majesty himself and granted him a pension, which corresponded to Šafarik's previous full pay. Šafárik died in 1861 in Prague. | In 1856/57, as a result of persecution anxieties, overwork, and ill health, he became physically and mentally insane and burned most of his correspondence with important personalities (e. g. with Ján Kollár). In May 1860, his [[clinical depression|depression]]s made him to jump into the [[Vltava]] river, but he was saved. This event produced considerable sensation among the general public. In early October 1860 he asked for retirement from his post as University Library head. The Austrian [[emperor]] himself enabled him this in a letter written by his majesty himself and granted him a pension, which corresponded to Šafarik's previous full pay. Šafárik died in 1861 in Prague. | ||

| + | Safarik developed his scientific work and held many jobs: as an editor with the Světozor magazine, fine arts censor, editor of a museum publication, and director of the University Library. In order to allow for Čelakovsky’s return to Prague, he resigned as professor at the university. | ||

| + | |||

| + | i z Nového Sadu udržoval styky s českými i slovenskými obrozenci, především s. Nicméně těžce nesl svoji odloučenost. Přestěhovat do Prahy se mu však podařilo teprve v květnu 1833. Umožnil mu to F. Palacký, který pro něj zajistil od skupiny českých vlastenců podporu ve výši 480 zlatých ročně. Aby dostatečně hmotně zajistil svou početnou rodinu, redigoval Šafařík v letech 1834-35 časopis Světozor, v letech 1838 až 1842 Časopis českého musea a od roku 1837 byl deset let censorem. Trvalejším zajištěním pak bylo jmenování kustodem (1841) a později (1848) ředitelem universitní knihovny. V březnu 1848 se stal také profesorem nově zřízené katedry slovanské filologie na pražské universitě. Po roce se však této funkce za nastupující reakce vzdal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Šafařík průkopnicky zasáhl do mnoha oborů slavistiky. Jeho stěžejním dílem jsou Slovanské starožitnosti, vydané v letech 1836 a 1837 a věnované nejstarším dějinám Slovanů. Šafařík v nich prokázal starobylost Slovanů a jejich nezastupitelný podíl při vytváření evropských dějin a kultury. Tím se jeho dílo stalo aktuálním nejen pro Čechy, ale i pro další malé slovanské národy, v té době nesvébytné, podceňované a bez vlastní státní organizace. Slovanské starožitnosti byly přeloženy do mnoha jazyků a přinesly Šafaříkovi evropský ohlas a řadu vědeckých poct. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Velmi úspěšná byla i další Šafaříkova práce Slovanský národopis, vydaná v létě 1842. Shrnul v ní základní údaje o současnosti slovanských národů, jejich počtu, sídlech, jazyku a literatuře. | ||

===Vienna=== | ===Vienna=== | ||

Revision as of 04:41, 2 January 2007

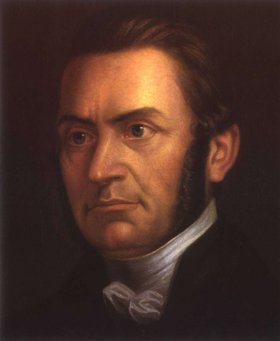

Pavel Josef Šafařík, ( May 13 1795 in Kobeliarovo, Slovakia, at that time part of the Kingdom of Hungary - June 26 1861 in Prague, Czech Republic, at that time part of the Austrian Empire) was a mezi nejvýznamnější osobnosti českého a slovenského národního obrození a mezi slavisty evropského významu. Slovak philologist, poet, one of the first scientific Slavists; literary historian, historian and ethnographer. zakladatel slovanské archeologie: // literární historik // básník // literární teoretik: He wrote most of his texts in Czech or in German.

Quotations

“I never detested work, but I could not always follow the voice of my heart; most of the time I had to follow the order of duty and deprivation, and many a time did I shiver, even sink, under the weight of life.”

“The nation which, aware of the importance of a natural language to its higher spiritual life, condemns it and gives it up, commits suicide and violates God’s eternal laws.” http://citaty.kukulich.net/autori/ss/

Family

His father was a teacher and Protestant clergyman in the town where Pavel was born. His mother, Katarína Káresová, came from a lower gentry family and juggled several jobs in order to help support the family. In 1813, after Katarína's death, Šafárik's father married the widowed Rozália Drábová against the wishes of Pavel and his siblings. The father noticed Pavel’s extraordinary talents and decided to bring him up as his successor. That is why Pavel was sent to a Protestant educational institution in Kežmarok (1810 to 1814) after graduation from the high school in Rožňava and Dobšiná and afterwards to university in Jena, Germany (1815 to 1817). Since Safarik was not keen on theology, he decided to become a teacher, which brought him to Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, where he worked as a tutor. Here he also met with František Palacký. In September of 1819 he assumed the position of a high school director in Novi Sad, Serbia. In his 14 years of working in this city, Safarik devoted to scientific research, and so when he moved to Prague in 1833, he was a recognized expert.

In 1822, while in Serbia, Šafárik married the 19 years old Júlia Ambróziová, a highly intelligent member of Slovak lower gentry who spoke Slovak, Czech, Serbian, and Russian and supported her husband in his scientific work. They had 11 children, of which seven survived.

The eldest son Vojtech, an accomplisched chemist, wrote a biography of his father’s life Co vyprávěl P. J. Šafařík (What Šafárik Talked About). Daughter Božena married Josef Jireček, a Czech literary historian and politician and previously a tutor in Šafarík's family. Vojtech together with Božena’s son and husband wrote a study Šafařík mezi Jihoslovany (Šafárik among Yougoslavs).

As his fellow countryman Kollár did through his poetic ideas, so did Šafařík through his scientific work promote the development of Panslavism, which was the pillor of the patriotic movement of his time. Unlike Kollár and many Czech Slavists, his concept of Panslavism did not hinge on the adulatory worship of Russia; during the Polish uprising in 1830, Šafařík was the only leader of the nationalist movement to take the side of the Poles.

His poor health took a visible turn for the worse in the second half of 1850s, also due to the suffocating atmosphere of Bach’s absolutism, fears of police persecution. Exhaustion coupled with a mental disease resulted in a suicide attempt at the age of 65 by jumping off the bridge into the river Vltava in Prague. He was rescued bud died a year later, in Prague.

Europe in 18th Century

The Czech nationalist movement was a reaction to the new ideological stream, Enlightement, spread from France and its authors of encyclopedias, such as Denis Diderot, D’Alambert, Voltaire, and Jean Jacques Rousseau. Enlightement was based on two schools of thought — Rene Descartes’ Rationalism, which introduced natural sciences, and John Locke’s Empiricism, which heralded sensualism. It was the beginning of the disintegration of the feudal system and the start of social reform, which was to be achieved through reason and science that would thus overcome religious dogma and political absolutism.

Enlightement had an effect on European monarchs: Maria Theresa introduced compulsory education, separated education from churches, and extended education even to children from poor families. Her son and successor Joseph II abolished serfdom in the Czech Lands and established freedom of religion. He also relegated to history the censorship of press. However, when his brother, Leopold II, took over, he was forced to revoke most patents except the one that brought an end to serfdom and the existence of one religion. Leopold’s son Franz I took a radical, anti-revolutionary, course and introduced severe censorship and monitoring of foreigners’ activities.

The Czech nationalist movement (1770 to 1850) is marked by strong patriotism and, as a reaction to the enforcement of the German language as the official language of the centralized Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, anti-German sentiment. The focus was on rational thought and science, hence the flourishing of scientific literature. The Czech nation and equalization of its culture within the monarch was seen as crucial in culture and politics. Initially these ideas were spread by patriotic priests and teachers.

In the first, “defensive”, stage of the Czech nationalist movement (1770s to 1800s), the emphasis was on science, the Czech language, national history, and culture. This period also saw a development of editing and establishment of scientific and educational institutions.

The second, “offensive”, stage (1800s to 1820s), was the period of scientists and poets. fundamentals of the Panslavic program were formed, which addresses the issues of all Slavs as a whole, headed by the Russian Empire. Major figures of the movement — Pavel Josef Šafařík along with Josef Jungmann, Jan Kollár, and František Palacký — were active. This stage was influenced by Napoleonic Wars and nationalist movements in Europe, which spurred the development of poetic and scientific language, expansion of vocabulary, study of history, rehabilitation of the Hussite heritage and other famous moments in the history of the Czechs but also creation of new values, pre-Romantic enthusiasm and faith in the future of the nation, resurrection of epic, and international cooperation. http://otazky.valek.net/mot05.html

The third stage (1830s to 1850s) was a culmination of nationalist activities, with its focus on the linguistic needs of the nation. The concept of Panslavism underwent its first major crisis, when the younger generation of Czech patriots realized the gap between the needs of Slavic nations and the despotism of Russian tzar tzarism. This desilusion, coupled with the goals of the German nationalist movement to unite Germany, which would include the heavy German population in the Czech Lands, grew into a new political definition of Slavism in 1840s — Austroslavism — which replaced Kollár’s abstract concept of mutual cooperation among Slavs with the program of cooperation among oppressed Slavic nations within the monarchy and transformation of the monarchy into a constitutional federal state, where Slavic needs would be addressed.

The neo-absolutism of 1850s, under the reign of Emperor Francis Joseph and his aid, Baron Alexander von Bach, terminated all political rights and, consequently, brought the Czech political life to a halt. Political activities were thus assumed by national culture. Once the neo-absolutist experiment ground to a halt, the Czechs rejected the Austro-Hungarian dualism; instead they insisted on the formation of the Czech state.

Life and Works

Slovakia (1795 - 1815)

Šafárik spent his childhood in the Kobeliarovo region of eastern Slovakia, known for its beautiful scenery and folk traditions. As his son Vojtech wrote in his book What Šafárik Talked About : When, at the age of 7, his father showed him only one letter of the alphabet, he taught himself to read, and from that time on was always sitting on the stove and reading. By the age of eight, he had read the whole Bible twice, and among his favorite activities was preaching to his brothers and sister as well as to local people.

Between 1805 and 1808, Šafárik studied at junion high school, described by some sources as Protestant, and then at the Latin high school for older children in Rožnava, where he learned Latin, German, and Hungarian. For lack of finances, he had to continue the studies in Dobšiná for two years, since his sister lived there and gave him shelter. In the Slovakia of that time, no one could practice science successfully in the Kingdom of Hungary without having a good command of Latin, German, Hungarian, and Slovak languages. Since the school in Rožňava specialized in Hungarian language and the school in Dobšiná in German, and Šafárik was an excellent student, plus both schools were reputable, all prerequisites for a successful career were met when he was 15.

Between 1810 and 1814, he studied at the high school in|Kežmarok, where he met Polish, Serbian and Ukrainian students and made an important friend of Ján Blahoslav Benedikti, with whom he read texts of Slovak and Czech national revivalists, especially by Josef Jungmann. He also read Classical literature and texts on German esthetics and became interested in Serbian culture. He graduated from philosophy, politics and law, and theology. What he learned here played a very important role in his life, as he noted, and since it was a largely German school, it opened doors for him for a partial scholarship for university studies in Germany.

He supported his studies working as a tutor. His first major work was a volume of poems The Muse of Tatras with a Slavonic Lyre published in 1814. The poems were written in the old-fashioned vernacular based on the Moravian Protestant translation of the Bible, the language the Slovak Lutherans used for published works. It was interspersed with Slovak and Polish words.

Germany (1815 - 1817)

In 1815 he took up studies at the University of Jena, which turned him from a poet into a scientist. This university was selected based on the wish of his father, who sponsored his son's studies there.

Here Šafárik attended lectures in history, philology, philosophy, and natural sciences. He read German poet, critic, theologian, and philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder and philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, as well as modern and classical literature. He translated into Czech Aristophanes' Clouds and Schiller's Maria Stuart. In 1816 he joined Jena's Latin Society (Societas latina Jenensis). Seventeen of his poems appeared in Prvotiny pěkných umění in Vienna, which made him well known in both Slovakia and Bohemia. He liked Jena; here he learned to apply scientific methods and found a lot of friends, such as Slovak writer Ján Chalúpka. Although Šafárik was an excellent student, he had to leave the university in May 1817 for unknown reasons, most likely the lack of finances.

On his way back to Slovakia, he stopped in Prague to search for a tutor position and ended up spending one month there. He joined the literary circle of the famous Czech national revivalists Josef Dobrovský, Josef Jungmann, and Václav Hanka.

Back in Slovakia (1817 - 1819)

Between the summer of 1817 and June of 1819, he worked as a tutor in Bratislava in the family of the well-known Gašpar Kubínyi. He befriended the founder of modern Czech historiography František Palacký, with whom he had already exchanged letters earlier. Palacký was also tutoring in Bratislava, the social and intellectual center of the Kingdom of Hungary. In the spring of 1819, Šafárik's circle of friends grew to include major Slovak writer and politician Ján Kollár.

In 1819, Benedikti helped him with a doctor's degree, necessary for the position of the headmaster of a newly established high school in Serbia's center of culture Novi Sad. Benedicti, together with some major Serbian figures, even manipulated the selection procedure to make sure that Šafárik, being the youngest and thus the least qualified applicant, was chosen as the new head.

Before he departed for Serbia, Šafárik spent some time in his hometown, and this was the last time he has seen his native country.

Serbia (1819 - 1833)

Here he held the position of headmaster and professor at the [Serbians Orthodox high school in Novi Sad, then the southern corner of the Kingdom of Hungary. He was the only non-Serbian professor. He taught mathematics, physics, logic, rhetoric, poetry, stylistics and Classic Literature in Latin, German, and Hungarian languages when Hungarisation ("Magyarisation") intensified. From 1821 on, he also tutored in a family related to the Serbian patriarch — head of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Being a man of great intellectual capacity, he also found time to study Serbian literature and archeology. He acquired numerous rare, especially Old Slavonic sacred books and manuscripts, which came handy in Prague. He poured his love of his native country into a collection of Slovak folk songs and sayings, to which Kollár and others contributed. In 1826 followed Geschichte der slawischen Sprache und Literatur nach allen Mundarten — the first attempt at a systematic account of Slavonic languages.

In 1824, the Austrian government's prohibition of employment of Protestants from the Kingdom of Hungary by the Serbian Orthodox Church caused him the loss of his job as headmaster and of the major source of income, in a situation when his family has grown substantially. He looked for a professorial position in Slovakia but without success.

Bohemia (1833 - 1861)

While in Novi Sad, Šafařík maintained contact with Czech and Slovak revivalists, especially with Kollár, but isolation from his fellow Czech and Slovak revivalists was very hard to bear. Only in 1833 was he able to move to Prague, after an unsuccessful search for a teacher or librarian tenure in Russia. It was Kollár, aided by his influential friends in Prague, who promised to finance his sojourn in Prague, which was to become his adoptive homeland until his death. He literally depended, especially in the 1840s, on 380 guldens annually, a stipend from his Czech friends under the condition that, as Palacký explicitly said, "from now on, anything you write, you will write it in the Czech language only".

Šafárik supported his meager income as an editor of the Světozor journal until poverty compelled him to accept the job of a censor of Czech publications in 1837, which he abandoned ten years later. For four years he was first editor, then director of the journal Časopis Českého musea. Since 1841 he was a custodian of the Prague University Library.

In Prague, he published most of his works, especially his greatest Slovanské starožitnosti. He also edited the first volume of Vybor (selected works by early Czech writers), which came out under the auspices of the Prague literary society.

Šafárik’s Stance on Slovak Language and Slovakia

In "Hlasowé o potřebě jednoty spisowného jazyka pro Čechy, Morawany a Slowáky" [Voices on the Necessity of a United Literal Language for the Czechs, Moravians and Slovaks] published by Kollár in 1846, Šafárik moderately criticized Ľudovít Štúr's introduction of a new Slovak standard language from 1843. Štúr namely replaced the previously employed Lutheran vernacular, which was closer to the Czech language. Slovak Catholics used a different vernacular.

Contrary to most of his Czech friends, Šafárik considered the Slovaks a separate nation from the Czechs, and he said so in his Geschichte der slawischen Sprache . . . and in Slovanský národopis. However, he did not advocate a separate Slovak language, only the Slovak vernacular of it as the language of Slovak literature.

During the Revolution of 1848 he was mainly collecting material for books on the oldest Slavic history (see Works). In 1848 he was made head of the University Library of Prague and an extraordinary professor of Slavonic philology in the University of Prague, but resigned to the latter in 1849 and remained head of the university library only. The reason for this resignation was that during the Revolution of 1848-49 he participated at the Slavic Congress in Prague (June 1848) and thus became suspicious for Austrian authorities. During the absolutistic period following the defeat of the revolution, he lived a secluded life and studied especially older Czech literature and Old Church Slavonic texts and culture.

In 1856/57, as a result of persecution anxieties, overwork, and ill health, he became physically and mentally insane and burned most of his correspondence with important personalities (e. g. with Ján Kollár). In May 1860, his depressions made him to jump into the Vltava river, but he was saved. This event produced considerable sensation among the general public. In early October 1860 he asked for retirement from his post as University Library head. The Austrian emperor himself enabled him this in a letter written by his majesty himself and granted him a pension, which corresponded to Šafarik's previous full pay. Šafárik died in 1861 in Prague. Safarik developed his scientific work and held many jobs: as an editor with the Světozor magazine, fine arts censor, editor of a museum publication, and director of the University Library. In order to allow for Čelakovsky’s return to Prague, he resigned as professor at the university.

i z Nového Sadu udržoval styky s českými i slovenskými obrozenci, především s. Nicméně těžce nesl svoji odloučenost. Přestěhovat do Prahy se mu však podařilo teprve v květnu 1833. Umožnil mu to F. Palacký, který pro něj zajistil od skupiny českých vlastenců podporu ve výši 480 zlatých ročně. Aby dostatečně hmotně zajistil svou početnou rodinu, redigoval Šafařík v letech 1834-35 časopis Světozor, v letech 1838 až 1842 Časopis českého musea a od roku 1837 byl deset let censorem. Trvalejším zajištěním pak bylo jmenování kustodem (1841) a později (1848) ředitelem universitní knihovny. V březnu 1848 se stal také profesorem nově zřízené katedry slovanské filologie na pražské universitě. Po roce se však této funkce za nastupující reakce vzdal.

Šafařík průkopnicky zasáhl do mnoha oborů slavistiky. Jeho stěžejním dílem jsou Slovanské starožitnosti, vydané v letech 1836 a 1837 a věnované nejstarším dějinám Slovanů. Šafařík v nich prokázal starobylost Slovanů a jejich nezastupitelný podíl při vytváření evropských dějin a kultury. Tím se jeho dílo stalo aktuálním nejen pro Čechy, ale i pro další malé slovanské národy, v té době nesvébytné, podceňované a bez vlastní státní organizace. Slovanské starožitnosti byly přeloženy do mnoha jazyků a přinesly Šafaříkovi evropský ohlas a řadu vědeckých poct.

Velmi úspěšná byla i další Šafaříkova práce Slovanský národopis, vydaná v létě 1842. Shrnul v ní základní údaje o současnosti slovanských národů, jejich počtu, sídlech, jazyku a literatuře.

Vienna

Veřejnému politickému vystupování se Šafařík vyhýbal. Výjimkou byl rok 1848. Když na jaře 1848 pracoval ve Vídni v komisi pro reformu školství, udržoval styky s některými představiteli vlády a stal se jakýmsi emisarem české liberální politiky ve Vídni. Předložil a veřejně zdůvodnil požadavek vyučování v českém jazyce. Zúčastnil se příprav i práce Slovanského sjezdu a patřil k jeho nejvýznamnějším osobnostem. Mohutným dojmem na účastníky sjezdu zapůsobil svým projevem v závěru prvního dne jednání.

Works

His most important works are: Mladý Šafařík, nadšený vlastenec ovlivněný především Jungmannovými myšlenkami, se zprvu věnoval literární činnosti. Psal verše (1814 vydal sbírku básní Tatranská Músa s lýrou slovanskou), překládal z antické a německé literatury, sbíral a vydával lidové písně a zabýval se i teorií literatury. Spolu s Palackým, vydali v březnu 1818 anonymní publikaci Počátkové českého básnictví. V hlavní otázce - vystoupení proti Dobrovského přízvučné prozodii - jim vývoj nedal za pravdu. Přesto však vlastenecký patos autorů, kritika dosud slabé úrovně české poezie a požadavek jazykem i obsahem vyspělé české literatury pozitivně ovlivnily její vývoj. Postupem doby Šafařík literární činnosti zanechal a věnoval se vědecké práci. Již v roce 1826 vyšly jeho německy psané Dějiny slovanského jazyka a literatury ve všech nářečích, které byly prvním pokusem o ucelený obraz historie slovanských jazyků a písemnictví.

Dílo:

- Tatranská Múza s lýrou slovanskou (1814) - svazek veršů

- Počátkové českého básnictví, obzvláště prozódie (1818) – vydal spolu s F. Palackým. V díle je vyzdvihnut názor, že český verš by měl být časoměrný (nositelem veršovaného rytmu má být střídání dlouhých a krátkých slabik). Tímto dílem vystoupili proti dosavadní básnické praxi, především proti poezii Puchmajerových almanachů.

- Dějiny slovanského jazyka a literatury podle všech nářečí (1826) - německy psané

- Slovanské starožitnosti (1837) - nejvýznamnější dílo. Zachycuje slovanské dějiny od počátku do konce 1. tisíciletí. Vyjádřil názor, že Slované zaujímají stejné místo jako Řekové, Římané a Germáni. Dílo bylo přeloženo do ruštiny, polštiny, němčiny a francouzštiny a nadlouho se stalo základní učebnicí na univerzitních katedrách slavistiky.

- Slovanský národopis (1842) – podává obraz slovanských národů v přítomnosti s údaji o jejich územním rozložením, počtu obyvatel, kultuře, vývoji a stavu literatury.

http://zivotopisy.ireferaty.cz/100/546/Safarik-Pavel-Josef

V 50. letech se Šafařík zabýval především otázkami staroslověnského jazyka. Jeho nejvýznamnější prací z tohoto období je dílo O původu a vlasti hlaholice (1858). Přinesl v něm řadu důkazů o tom, že hlaholice je starším typem písma než cyrilice. Vyřešil tak dlouhodobý spor slavistů, v němž dříve zaujímal stanovisko opačné. Svědčilo to o vědecké poctivosti Šafaříka, pro kterého neustálé hledání pravdy bylo základním vědeckým i morálním principem. Jeho obrovská morální síla se projevila i v poměru k Hankovým padělkům starých českých rukopisů. Patřil mezi ty, kteří uvěřili v jejich pravost, a ještě v roce 1840 ji spolu s Palackým obhajoval. Koncem 50. let se účastnil práce komise, která zjistila, že Milostná píseň krále Václava a také Píseň vyšehradská jsou padělky. V přednášce v Královské české společnosti nauk v prosinci 1859 pak vyjádřil pochybnosti o pravosti Rukopisu zelenohorského.

a) Poetry:

- Ode festiva... (Levoča, 1814), an ode to the baron and colonel Ondreja Máriassy, the patron of the Kežmarok lyceum, on the occasion of his return from the war against Napoleon

- Tatranská múza s lyrou slovanskou (Levoča, 1814) [literally: 'The Muse of Tatras with a Slavonic Lyre] - poems inspired by Classical, contemporaneous European literature (Friedrich Schiller) and by Slovak traditions and legends (Juraj Jánošík)

b) Scientific Works:

- Promluvení k Slovanům [literally: An address to the Slavs] in: Prvotiny pěkných umění (1817, ?) - inspired by Herder and other national literatures, he calls the Slovaks, Moravians and Czechs to collect folk songs

- Počátkové českého básnictví, obzvláště prozodie (1818, Bratislava), together with František Palacký [literally:Basics of Czech poetry, in particular of the prosody] - deals with technical issues of poetry writing

- Novi Graeci non uniti ritus gymnasii neoplate auspicia feliciter capta. Adnexa est oratio Pauli Josephi Schaffarik (1819, Novi Sad)

- Písně světské lidu slovenského v Uhřích. Sebrané a vydané od P. J. Šafárika, Jána Blahoslava a jiných. 1-2 (Pest 1823-1827) /Národnie zpiewanky- Pisne swetské Slowáků v Uhrách (1834-1835, Buda), together with Jan Kollár [literally: Profane songs of the Slovak people in the Kingdom of Hungary. Collected and issued by P. J. Šafárik, Ján Blahoslav and others. 1-2 / Folk songs - Profane songs of the Slovaks in the Kingdom of Hungary] -

- Geschichte der slawischen Sprache und Literatur nach allen Mundarten (1826, Pest), [literally:History of the Slavic language and literature by all vernaculars] - a huge encyclopedia-style book, the first attempt to give anything like a systematic account of the Slavonic languages as a whole.

- Über die Abkunft der Slawen nach Lorenz Surowiecki (1828, Buda) [literally: On the origin of the Slavs according to Lorenz Surowiecki] - aimed to be a reaction the Surowiecki's text, the text developed into a book on the homeland of the Slavs

- Serbische Lesekörner oder historisch-kritische Beleuchtung der serbischen Mundart (1833, Pest) [literally: Serbian anthology or historical and critical elucidation of the Serbian vernacular] - explanation of the character and development of the Serbian language

- Slovanské starožitnosti(1837 + 1865, Prague) [Slavonic Antiquities], his main work, the first bigger book on the culture and history of the Slavs, a second edition (1863) was edited by Josef Jireček (see Family), a continuation was published only after Šafáriks death in Prague in 1865; a Russian, German and Polish translation followed immediately; the main book describes the origin, settlements, localisation and historic events of the Slavs on the basis of an extensive collection of material; inspired by Herder's opinions, he refused to consider the Slavs as Slaves and barbarian as was frequent at that time especially in German literature; the book substantially influenced the view of the Slavs

- Monumenta Illyrica (1839, Prague) - monuments of old Southern Slavic literature

- Die ältesten Denkmäler der böhmischen Sprache... (1840, Prague) [literally: The oldest monuments of Czech language . . . ], together with František Palacký

- Slovanský národopis (1842- 2 editions, Prague) [literally: Slavic ethnology], his second most important work, he sought to give a complete account of Slavonic ethnology; contains basic data on individual Slavic nations, settlements, languages, ethnic borders, and a map, on which the Slavs are formally considered one nation divided into Slavic national units

- Počátkové staročeské mluvnice in: Výbor (1845) [literally: Basics of Old Czech grammar]

- Juridisch - politische Terminologie der slawischen Sprachen Oesterreich (Vienna, 1850) [Legal and political terminology of the Slavic languages in Austria], a dictionary written together with Karel Jaromŕr Erben, Šafárik and Erben became - by order of Alexander Bach members of a committee for Slavic legal terminology in Austria

- Památky dřevního pisemnictví Jihoslovanů (1851, Prague) [literally: Monuments of old literature of the Southern Slavs] - contains important Old Church Slavonic texts

- Památky hlaholského pisemnictví (1853, Prague) [literally: Monuments of the Glagolitic literature]

- Glagolitische Fragmente (1857, Prague), together with Höfler [literally: Glagolitic fragments]

- Über den Ursprung und die Heimat des Glagolitismus (1858, Prague) [literally: On the origin and the homeland of the Glagolitic script] - here he accepted the view that the Glagolitic alphabet is older than the Cyrillic one

- Geschichte der südslawischen Litteratur1-3 (1864-65, Prague) [literally: History of Southern Slavic literature], edited by Jireček

c) Collected works:

- Sebrané spisy P. J. Šafaříka 1-3 (Prague 1862-1863 + 1865)

d) Collected papers:

- Spisy Pavla Josefa Šafaříka 1 (Bratislava, 1938)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

http://www.libri.cz/databaze/kdo18/search.php?zp=5&name=%A9AFA%D8%CDK+PAVEL+JOSEF http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-2429/Francis-Joseph http://www.maturita.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=2618 (both articles)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.