Difference between revisions of "Maimonides" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) m |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}} |

| − | '''Moshe ben Maimon''' ( | + | [[Image:Maimonides-2.jpg|thumb|200px|An artist's conception of Maimonides' appearance]] |

| − | + | '''Moshe ben Maimon''' (March 30, 1135 – December 13, 1204) was a Jewish [[rabbi]], physician, and philosopher. Moshe ben Maimon's Hebrew name is רבי משה בן מיימון and his Arabic name is موسى بن ميمون بن عبد الله القرطبي الإسرائيلي, '''Mussa bin Maimun ibn Abdallah al-Kurtubi al-Israili'''. However, he is most commonly known by his Greek name, '''Moses Maimonides''' (Μωησής Μαϊμονίδης), and many Jewish works refer to him by the acronym of his title and name, '''RaMBaM''' or '''Rambam''' (רמב"ם). | |

| − | Moshe ben Maimon's | + | {{toc}} |

| + | Maimonides is typically regarded as the greatest of the medieval Jewish philosophers. His work is unhesitatingly rationalist in spirit, both in his attempts to provide rational grounds for traditional Jewish law and in his picture of philosophy and rational inquiry as constitutive of the end of the perfection of the soul. Much of this stems from Maimonides' being heavily influenced by the work of [[Aristotle]]. His influence has been vast, both on the Jewish and Christian traditions (ranging from [[Thomas Aquinas|Aquinas]] to [[Baruch_Spinoza|Spinoza]]). By achieving a synthesis between Hebraism and Hellenism, revelation and reason, Maimonides laid the foundation for the extraordinary contribution that Jews made to Western literature, music, science, technology, law, politics, cinema, academia, commerce, finance, medicine, and art. | ||

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| − | [[Image:Maimonides-Statue.jpg|thumb|Statue of Maimonides in Córdoba, Spain]] | + | [[Image:Maimonides-Statue.jpg|thumb|200px|Statue of Maimonides in Córdoba, Spain]] |

| − | Maimonides was born in | + | Maimonides was born in 1135 in Córdoba, [[Spain]], then under Muslim rule. Maimonides studied [[Torah]] under his father Maimon. The [[Almohades]] conquered Córdoba in 1148, and offered the Jewish community the choice of conversion to Islam, death, or exile. Maimonides's family, along with most other Jews, chose exile. For the next ten years they moved about in southern Spain, eventually settling in Fez, [[Morocco]]. While there, Maimonides wrote his first significant philosophical work (the ''Treatise on the Art of Logic'') and began on his ''Commentary on the [[Mishnah]]''. |

| − | Following this sojourn in Morocco, he briefly lived in the Holy Land, spending time in [[Jerusalem]], and finally settled in | + | Following this sojourn in Morocco, he briefly lived in the [[Holy Land]], spending time in [[Jerusalem]], and finally settled in Fostat, [[Egypt]]. There, he worked as a physician and jurist, and became a leader of the Egyptian Jewish community. While there, he completed and published (around 1185) the 14-volume ''Mishneh Torah'', which remains a central work in Jewish law. The work aimed to find a systematic philosophical basis for traditional Jewish law, arguing that even the most particular laws were specifically aimed at promoting the perfection of the [[soul]] so that the soul can properly love God. |

| − | + | Maimonides' major philosophical work is the ''Guide for the Perplexed'', finished in 1190. The book is posed as an extended letter on the apparent conflict between religion and philosophy (primarily, [[Aristotelianism|Aristotelian philosophy]]). Maimonides considers a broad set of issues, often showing much more sympathy for the philosophical side of debates than many of his readers would find appropriate (the book was condemned and burned at Montpellier several decades after Maimonides' death). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The last parts of Maimonides' life were spent defending his views and pursuing issues in natural philosophy. He died in 1204, at which time his son Abraham became the head of the Egyptian Jewish community. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | == Philosophy == | |

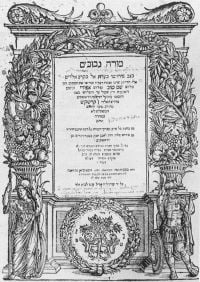

| − | + | [[Image:Guide for the Perplexed by Maimonides.jpg|thumb|200px|The title page of ''The Guide for the Perplexed'']] | |

| − | + | Through the ''Guide for the Perplexed'' and the philosophical introductions to sections of his commentaries on the Mishnah, Maimonides exerted an important influence on the [[Scholasticism|Scholastic]] philosophers, especially on [[Albertus Magnus|Albert the Great]], [[Thomas Aquinas]] and [[Duns Scotus]]. He himself was a Jewish Scholastic. Educated more by reading the works of Arab Muslim philosophers than by personal contact with Arab teachers, he acquired an intimate acquaintance not only with Arab Muslim philosophy, but also with the doctrines of [[Aristotle]]. Maimonides strove to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy and science, with the teachings of the Torah. The project of reconciliation had a specific motivation, for Maimonides believed that a single body of philosophical wisdom had influenced the Jewish patriarchs and the [[Greek philosophy|Greek philosophers]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | [[Image:Guide for the Perplexed by Maimonides.jpg|thumb|The title page of ''The Guide for the Perplexed'']] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==The 13 principles of faith== | + | ===The 13 principles of faith=== |

| − | |||

| − | In his commentary on the Mishna (tractate Sanhedrin, chapter 10), Maimonides formulates his '''13 principles of faith'''. They | + | In his commentary on the Mishna (tractate Sanhedrin, chapter 10), Maimonides formulates his '''13 principles of faith'''. They summarized what he viewed as the required beliefs of Judaism with regards to: |

| − | # The existence of God | + | # The existence of [[God]] |

| − | # God's unity | + | # [[God]]'s unity |

| − | # God's [[spirituality]] and [[ | + | # God's [[spirituality]] and [[incorporeal]]ity |

# God's [[eternity]] | # God's [[eternity]] | ||

# God alone should be the object of [[worship]] | # God alone should be the object of [[worship]] | ||

| − | # [[Revelation]] through God's [[ | + | # [[Revelation]] through [[God]]'s [[prophet]]s |

| − | # The preeminence of [[Moses]] among the | + | # The preeminence of [[Moses]] among the [[prophet]]s |

# God's law given on [[Mount Sinai]] | # God's law given on [[Mount Sinai]] | ||

| − | # The immutability of the [[Torah]] as God's Law | + | # The immutability of the [[Torah]] as [[God]]'s Law |

# God's foreknowledge of human actions | # God's foreknowledge of human actions | ||

# Reward of good and [[retributive justice|retribution]] of evil | # Reward of good and [[retributive justice|retribution]] of evil | ||

| − | # The coming of the | + | # The coming of the [[Jewish Messiah]] |

# The [[resurrection]] of the dead | # The [[resurrection]] of the dead | ||

| − | These principles were controversial when first proposed, evoking criticism by [[Hasdai Crescas]] and [[Joseph Albo]], and were effectively ignored by much of the Jewish community for the next few centuries. | + | These principles were controversial when first proposed, evoking criticism by [[Hasdai Crescas|Rabbi Hasdai Crescas]] and [[Joseph Albo|Rabbi Joseph Albo]], and were effectively ignored by much of the [[Judaism|Jewish]] community for the next few centuries.<ref>Menachem Kellner, ''Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought'' (Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004, ISBN 978-1904113218).</ref> However, these principles became widely held; today, [[Orthodox Judaism]] holds these beliefs to be obligatory. Two poetic restatements of these principles (''[[Ani Ma'amin]]'' and ''[[Yigdal]]'') eventually became canonized in the [[Siddur]] ([[Judaism|Jewish]] prayer book). |

| − | + | Given the scope of Maimonides' work, a proper survey would be beyond the scope of this article. We can therefore focus on three philosophical topics which were of special importance to Maimonides, and which exerted the greatest influence on later thinkers. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Negative theology=== | ===Negative theology=== | ||

| − | + | Maimonides was led by his admiration for the [[neoplatonism|neo-Platonic]] commentators to maintain many doctrines which the [[Scholasticism|Scholastics]] could not accept. For instance, Maimonides was an adherent of "[[negative theology]]." This approach to theology claims that we are incapable of positively characterizing God. For instance, a claim such as "God is wise" applies a predicate ('wise') to God which can also be applied to humans. This, however, implies that God's essence is of a kind with finite beings. | |

| − | Maimonides | + | Seeing such an implication as entirely unacceptable, Maimonides argued that such claims should be replaced with (e.g.) "God is not ignorant." In this latter claim, there is no implication that there is any positive characteristic that applies both the humans and to God; instead, the claim merely asserts that a certain predicate (one which is applicable to humans) is ''not'' applicable to God. These distinctions are for the most part foreign to contemporary discussions of [[logic]], though they can be found well into the eighteenth century (see, for instance, [[Immanuel Kant]]'s discussion of 'infinite' judgments). |

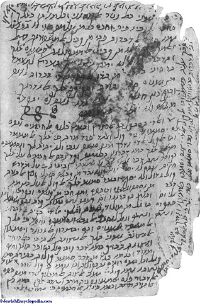

| + | [[Image:Manuscript page by Maimonides Arabic in Hebrew letters.jpg|thumb|200px|Manuscript page by Maimonides; Judeo-Arabic language in [[Hebrew alphabet|Hebrew]] letters]] | ||

| + | In connection with this, Maimonides argued extensively against [[anthropomorphism|anthropomorphic]] conceptions of God. Biblical descriptions of God which ascribe him a body or voice, he claimed, must be seen as metaphorical and as intended to instruct the unphilosophical. This anti-anthropomorphic approach to God doubtless had a strong influence on [[Baruch Spinoza]], though Spinoza's extreme [[rationalism]] and [[naturalism]] led him to reject negative theology. | ||

| − | + | ===Creation=== | |

| + | One of the most notable points in Maimonides' attempt to balance conflicting Jewish and Greek claims concerns the creation of the universe. Though he understood much of the [[Pentateuch]] as metaphorical, Maimonides regarded ''Genesis'' as a clear statement that the universe was created by God at some time the past. By contrast, the view of the Aristotelians (stemming from Aristotle's ''Physics'') was that the universe was eternal, and that God's influence was unchanging and eternal. | ||

| − | + | Maimonides weighs these two views carefully, and though he appears to favor the view in ''Genesis'', the lack of a definitive rejection of Aristotle's view has led some (such as [[Leo Strauss]]) to interpret his defense of the Biblical view as less than whole-hearted. Nevertheless, the argumentative force of the discussion is clearly aimed at showing the philosophical defensibility of the non-eternal view. Aristotle had argued in favor of an unchanging 'Prime Mover' on the basis of the apparently unchanging and necessary movements of the stars and planets. Unchanging motion, he thought, must have an unchanging source. Maimonides responded by challenging the necessity of celestial motions. Taking necessity to imply perfect order, he argued that the order of celestial bodies was far from perfect. For instance, perfect order would (he thought) require a proportional relation between the speed at which a body moved and its distance from the earth, yet no such relation existed. The lack of a perfect order meant a lack of necessity, and so the lack of an eternal source. In offering this argument, Maimonides was clear that he was merely making room for the Biblical account, not establishing it conclusively. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Practical Philosophy=== |

| − | Maimonides | + | For Maimonides, the central duties for all humans are to love God and avoid idolatry. Properly loving God requires the perfection of the soul, and since the soul is bound to the body, the body must be perfected as well. In his works on Jewish law, Maimonides argued that all traditional law was constructed with these aims. The role of the [[Messiah]], Maimonides claimed, would not be to perform [[miracles]], but rather to re-establish the state of [[Israel]] and make it a focal point of science and philosophy, whose purpose in turn would be the perfection of the soul. |

| − | + | Maimonides carefully considers the Aristotelian doctrine of the mean as a guide to proper living. He generally agrees with Aristotle that the health of the body (and so the health of the soul) requires avoiding excesses of both kinds. The agreement, however, is limited. Whereas Aristotle believed that a measured amount of control by our passions is part of living well, Maimonides rejects any practical tenets that would compromise the centrality of the intellect. Most people, he believed, will always be governed by their emotions, and for them the doctrine of the mean and the influence of external controls will be necessary. Yet those who can properly pursue the perfection of their souls through philosophy will not be controlled at all by their passions. | |

| − | Maimonides | ||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | === | + | ==References== |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | ===Primary sources=== |

| + | * Hyamson, M. (trans.). ''Maimonides: The Book of Knowledge''. Jerusalem: Feldheim, 1974. ISBN 0854050388 | ||

| + | * Pines, S. (ed.). ''Dalalat al-Ha’irin (Moreh Nevukhim, Guide to the Perplexed)''. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1969. ISBN 1852428260 | ||

| + | * Satnov, Y. (ed.). ''Millot ha-Higgayon (On Logic)''. Berlin: B. Cohen, 1927. | ||

| + | * Twersky, I. (ed.). ''A Maimonides Reader''. West Orange, NJ: Behrman House, 1972. ISBN 0874412064 | ||

| + | * Weis, R. and C. Butterworth (eds.). ''The Ethical Writings of Maimonides.'' New York: Butterworth, 1975. ISBN 0486245225 | ||

| − | + | ===Secondary sources=== | |

| + | * Buijs, J. ''Maimonides: A Collection of Critical Essays''. Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press, 1988. ISBN 0268013675 | ||

| + | * Davidson, Herbert. ''Moses Maimonides''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 019517321X | ||

| + | * Fox, Marvin. ''Interpreting Maimonides''. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1990. ISBN 0226259420 | ||

| + | * Kellner, Menachem. ''Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought''. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004. ISBN 978-1904113218 | ||

| + | * Seeskin, Kenneth. ''Maimonides on the Origin of the World''. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 052184553X | ||

| + | * Seeskin, Kenneth (ed.). ''The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides''. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0521525780 | ||

| + | * Strauss, Leo. "The Literary Character of the ''Guide to the Perplexed''," in ''Persecution and the Art of Writing''. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press, 1952. ISBN 0029320305 | ||

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| − | + | All links retrieved November 5, 2022. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/maimonides/ Maimonides] – The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | |

| − | + | *[http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Maimonides.html Moses Maimonides/Rambam] – The Jewish Virtual Library | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Maimonides.html Maimonides/Rambam] | ||

*[http://www.themystica.com/mystica/articles/m/maimonidean_controversy.html Maimonidean controversy] | *[http://www.themystica.com/mystica/articles/m/maimonidean_controversy.html Maimonidean controversy] | ||

| − | + | *[http://www.panix.com/~jjbaker/rambam.html Maimonides Page] – Links to online resources | |

| − | *[http://www.panix.com/~jjbaker/rambam.html Maimonides Page | ||

| − | |||

*[http://www.mechon-mamre.org/e/e0000.htm Rambam's introduction to the Mishnah Torah (English translation]) | *[http://www.mechon-mamre.org/e/e0000.htm Rambam's introduction to the Mishnah Torah (English translation]) | ||

*[http://www.daat.ac.il/daat/mahshevt/hakdama/tohen-m-2.htm Rambam's introduction to the Commentary on the Mishnah (Hebrew Fulltext)] | *[http://www.daat.ac.il/daat/mahshevt/hakdama/tohen-m-2.htm Rambam's introduction to the Commentary on the Mishnah (Hebrew Fulltext)] | ||

| − | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/gfp/ | + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/gfp/index.htm The Guide For the Perplexed by Moses Maimonides translated into English by Michael Friedländer] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===General Philosophy Sources=== | |

| + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | ||

| + | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | ||

| + | *[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online] | ||

| + | *[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg] | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[category:Philosophy and religion]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Biography]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Religion]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credit2|Maimonides|54991473|Maimonides|106225691}} |

Latest revision as of 05:30, 5 November 2022

Moshe ben Maimon (March 30, 1135 – December 13, 1204) was a Jewish rabbi, physician, and philosopher. Moshe ben Maimon's Hebrew name is רבי משה בן מיימון and his Arabic name is موسى بن ميمون بن عبد الله القرطبي الإسرائيلي, Mussa bin Maimun ibn Abdallah al-Kurtubi al-Israili. However, he is most commonly known by his Greek name, Moses Maimonides (Μωησής Μαϊμονίδης), and many Jewish works refer to him by the acronym of his title and name, RaMBaM or Rambam (רמב"ם).

Maimonides is typically regarded as the greatest of the medieval Jewish philosophers. His work is unhesitatingly rationalist in spirit, both in his attempts to provide rational grounds for traditional Jewish law and in his picture of philosophy and rational inquiry as constitutive of the end of the perfection of the soul. Much of this stems from Maimonides' being heavily influenced by the work of Aristotle. His influence has been vast, both on the Jewish and Christian traditions (ranging from Aquinas to Spinoza). By achieving a synthesis between Hebraism and Hellenism, revelation and reason, Maimonides laid the foundation for the extraordinary contribution that Jews made to Western literature, music, science, technology, law, politics, cinema, academia, commerce, finance, medicine, and art.

Biography

Maimonides was born in 1135 in Córdoba, Spain, then under Muslim rule. Maimonides studied Torah under his father Maimon. The Almohades conquered Córdoba in 1148, and offered the Jewish community the choice of conversion to Islam, death, or exile. Maimonides's family, along with most other Jews, chose exile. For the next ten years they moved about in southern Spain, eventually settling in Fez, Morocco. While there, Maimonides wrote his first significant philosophical work (the Treatise on the Art of Logic) and began on his Commentary on the Mishnah.

Following this sojourn in Morocco, he briefly lived in the Holy Land, spending time in Jerusalem, and finally settled in Fostat, Egypt. There, he worked as a physician and jurist, and became a leader of the Egyptian Jewish community. While there, he completed and published (around 1185) the 14-volume Mishneh Torah, which remains a central work in Jewish law. The work aimed to find a systematic philosophical basis for traditional Jewish law, arguing that even the most particular laws were specifically aimed at promoting the perfection of the soul so that the soul can properly love God.

Maimonides' major philosophical work is the Guide for the Perplexed, finished in 1190. The book is posed as an extended letter on the apparent conflict between religion and philosophy (primarily, Aristotelian philosophy). Maimonides considers a broad set of issues, often showing much more sympathy for the philosophical side of debates than many of his readers would find appropriate (the book was condemned and burned at Montpellier several decades after Maimonides' death).

The last parts of Maimonides' life were spent defending his views and pursuing issues in natural philosophy. He died in 1204, at which time his son Abraham became the head of the Egyptian Jewish community.

Philosophy

Through the Guide for the Perplexed and the philosophical introductions to sections of his commentaries on the Mishnah, Maimonides exerted an important influence on the Scholastic philosophers, especially on Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus. He himself was a Jewish Scholastic. Educated more by reading the works of Arab Muslim philosophers than by personal contact with Arab teachers, he acquired an intimate acquaintance not only with Arab Muslim philosophy, but also with the doctrines of Aristotle. Maimonides strove to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy and science, with the teachings of the Torah. The project of reconciliation had a specific motivation, for Maimonides believed that a single body of philosophical wisdom had influenced the Jewish patriarchs and the Greek philosophers.

The 13 principles of faith

In his commentary on the Mishna (tractate Sanhedrin, chapter 10), Maimonides formulates his 13 principles of faith. They summarized what he viewed as the required beliefs of Judaism with regards to:

- The existence of God

- God's unity

- God's spirituality and incorporeality

- God's eternity

- God alone should be the object of worship

- Revelation through God's prophets

- The preeminence of Moses among the prophets

- God's law given on Mount Sinai

- The immutability of the Torah as God's Law

- God's foreknowledge of human actions

- Reward of good and retribution of evil

- The coming of the Jewish Messiah

- The resurrection of the dead

These principles were controversial when first proposed, evoking criticism by Rabbi Hasdai Crescas and Rabbi Joseph Albo, and were effectively ignored by much of the Jewish community for the next few centuries.[1] However, these principles became widely held; today, Orthodox Judaism holds these beliefs to be obligatory. Two poetic restatements of these principles (Ani Ma'amin and Yigdal) eventually became canonized in the Siddur (Jewish prayer book).

Given the scope of Maimonides' work, a proper survey would be beyond the scope of this article. We can therefore focus on three philosophical topics which were of special importance to Maimonides, and which exerted the greatest influence on later thinkers.

Negative theology

Maimonides was led by his admiration for the neo-Platonic commentators to maintain many doctrines which the Scholastics could not accept. For instance, Maimonides was an adherent of "negative theology." This approach to theology claims that we are incapable of positively characterizing God. For instance, a claim such as "God is wise" applies a predicate ('wise') to God which can also be applied to humans. This, however, implies that God's essence is of a kind with finite beings.

Seeing such an implication as entirely unacceptable, Maimonides argued that such claims should be replaced with (e.g.) "God is not ignorant." In this latter claim, there is no implication that there is any positive characteristic that applies both the humans and to God; instead, the claim merely asserts that a certain predicate (one which is applicable to humans) is not applicable to God. These distinctions are for the most part foreign to contemporary discussions of logic, though they can be found well into the eighteenth century (see, for instance, Immanuel Kant's discussion of 'infinite' judgments).

In connection with this, Maimonides argued extensively against anthropomorphic conceptions of God. Biblical descriptions of God which ascribe him a body or voice, he claimed, must be seen as metaphorical and as intended to instruct the unphilosophical. This anti-anthropomorphic approach to God doubtless had a strong influence on Baruch Spinoza, though Spinoza's extreme rationalism and naturalism led him to reject negative theology.

Creation

One of the most notable points in Maimonides' attempt to balance conflicting Jewish and Greek claims concerns the creation of the universe. Though he understood much of the Pentateuch as metaphorical, Maimonides regarded Genesis as a clear statement that the universe was created by God at some time the past. By contrast, the view of the Aristotelians (stemming from Aristotle's Physics) was that the universe was eternal, and that God's influence was unchanging and eternal.

Maimonides weighs these two views carefully, and though he appears to favor the view in Genesis, the lack of a definitive rejection of Aristotle's view has led some (such as Leo Strauss) to interpret his defense of the Biblical view as less than whole-hearted. Nevertheless, the argumentative force of the discussion is clearly aimed at showing the philosophical defensibility of the non-eternal view. Aristotle had argued in favor of an unchanging 'Prime Mover' on the basis of the apparently unchanging and necessary movements of the stars and planets. Unchanging motion, he thought, must have an unchanging source. Maimonides responded by challenging the necessity of celestial motions. Taking necessity to imply perfect order, he argued that the order of celestial bodies was far from perfect. For instance, perfect order would (he thought) require a proportional relation between the speed at which a body moved and its distance from the earth, yet no such relation existed. The lack of a perfect order meant a lack of necessity, and so the lack of an eternal source. In offering this argument, Maimonides was clear that he was merely making room for the Biblical account, not establishing it conclusively.

Practical Philosophy

For Maimonides, the central duties for all humans are to love God and avoid idolatry. Properly loving God requires the perfection of the soul, and since the soul is bound to the body, the body must be perfected as well. In his works on Jewish law, Maimonides argued that all traditional law was constructed with these aims. The role of the Messiah, Maimonides claimed, would not be to perform miracles, but rather to re-establish the state of Israel and make it a focal point of science and philosophy, whose purpose in turn would be the perfection of the soul.

Maimonides carefully considers the Aristotelian doctrine of the mean as a guide to proper living. He generally agrees with Aristotle that the health of the body (and so the health of the soul) requires avoiding excesses of both kinds. The agreement, however, is limited. Whereas Aristotle believed that a measured amount of control by our passions is part of living well, Maimonides rejects any practical tenets that would compromise the centrality of the intellect. Most people, he believed, will always be governed by their emotions, and for them the doctrine of the mean and the influence of external controls will be necessary. Yet those who can properly pursue the perfection of their souls through philosophy will not be controlled at all by their passions.

Notes

- ↑ Menachem Kellner, Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought (Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004, ISBN 978-1904113218).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources

- Hyamson, M. (trans.). Maimonides: The Book of Knowledge. Jerusalem: Feldheim, 1974. ISBN 0854050388

- Pines, S. (ed.). Dalalat al-Ha’irin (Moreh Nevukhim, Guide to the Perplexed). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1969. ISBN 1852428260

- Satnov, Y. (ed.). Millot ha-Higgayon (On Logic). Berlin: B. Cohen, 1927.

- Twersky, I. (ed.). A Maimonides Reader. West Orange, NJ: Behrman House, 1972. ISBN 0874412064

- Weis, R. and C. Butterworth (eds.). The Ethical Writings of Maimonides. New York: Butterworth, 1975. ISBN 0486245225

Secondary sources

- Buijs, J. Maimonides: A Collection of Critical Essays. Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press, 1988. ISBN 0268013675

- Davidson, Herbert. Moses Maimonides. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 019517321X

- Fox, Marvin. Interpreting Maimonides. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1990. ISBN 0226259420

- Kellner, Menachem. Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004. ISBN 978-1904113218

- Seeskin, Kenneth. Maimonides on the Origin of the World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 052184553X

- Seeskin, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0521525780

- Strauss, Leo. "The Literary Character of the Guide to the Perplexed," in Persecution and the Art of Writing. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press, 1952. ISBN 0029320305

External links

All links retrieved November 5, 2022.

- Maimonides – The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Moses Maimonides/Rambam – The Jewish Virtual Library

- Maimonidean controversy

- Maimonides Page – Links to online resources

- Rambam's introduction to the Mishnah Torah (English translation)

- Rambam's introduction to the Commentary on the Mishnah (Hebrew Fulltext)

- The Guide For the Perplexed by Moses Maimonides translated into English by Michael Friedländer

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.