Boltzmann, Ludwig

Peter Duveen (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | {{epname}} | + | {{epname|Boltzmann, Ludwig}} |

{{Infobox_Scientist | {{Infobox_Scientist | ||

| name = Ludwig Boltzmann | | name = Ludwig Boltzmann | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann''' (February 20, 1844 – September 5, 1906) was an [[Austria]]n [[physicist]] famous for his | + | '''Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann''' (February 20, 1844 – September 5, 1906) was an [[Austria]]n [[physicist]] famous for his application of probability theory to the study of [[molecule]]s in a [[gas]]. He used the results of his theoretical investigations to explain the thermodynamic properties of materials. He was one of the most important advocates of the [[atomic theory]] when that scientific model was still highly controversial. Other scientists extended his work to express what became known as [[quantum mechanics]]. His personal life, however, was clouded with bouts of [[depression]] and he ended it with [[suicide]]. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ==Biography== | ||

| + | === Childhood === | ||

| − | == | + | Boltzmann was born in [[Vienna]], then capital of the [[Austrian Empire]]. He was the eldest of three children of Ludwig Georg Boltzmann, a tax official, and Katarina Pauernfeind of [[Salzburg]]. He received his primary education from a private tutor at the home of his parents. Boltzmann attended high school in [[Linz]], [[Upper Austria]]. As a youth, his interests encompassed literature, butterfly collecting, and music. For a short time, he studied piano under the famous composer [[Anton Bruckner]]. At age 15, Boltzmann lost his father to tuberculosis. |

| − | == | + | |

| + | ===University years=== | ||

| + | Boltzmann studied [[physics]] at the [[University of Vienna]], starting in 1863. Among his teachers were [[Johann Josef Loschmidt|Josef Loschmidt]], who was the first to measure the size of a molecule, and [[Joseph Stefan]], who discovered the law by which radiation depends on the temperature of a body. Stefan introduced Boltzmann to [[James Clerk Maxwell|Maxwell]]'s work by giving him some of Maxwell's papers on electricity, and an English grammar book to help him learn English. Loschmidt and Stefan, Boltzmann's chief mentors during this period, became his close friends. The laboratory in which they worked, in a private house separate from the university campus, was sparsely equipped. "We always had enough ideas," Boltzmann would later say. "Our only worry was the experimental apparatus."<ref>Jagdish Mehra and Helmut Rechenberg, ''The Historical Development of Quantum Theory'' (New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001). ISBN 0387906428</ref> Boltzmann published his first paper, on the electrical resistance between different points on a conducting sphere, in 1865. He received his doctorate in 1866, working under Stefan's supervision. | ||

| − | + | ===Early research=== | |

| − | + | In this same year, he published his first paper on the kinetic theory of gases, entitled, "On the mechanical significance of the second law of thermodynamics." In 1867, he became a [[Privatdozent]] (lecturer). Boltzmann worked two more years as Stefan’s assistant. The following year, Boltzmann published a paper, "Studies on the equipartition of thermal kinentic energy among material point masses," in which he attempted to express the manner in which energy was distributed among the trillions of molecules in a sample of gas.<ref>William R. Everdell, ''The First Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth-Century Thought'' (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997). ISBN 0226224805</ref> | |

=== Academic career === | === Academic career === | ||

| − | In 1869, at age 25, he was appointed full Professor of Mathematical Physics at the [[University of Graz]] in the province of [[Styria]]. In 1869 he spent several months in [[Heidelberg]] working with [[Robert Bunsen]] and [[Leo Königsberger]] and then in 1871 he was with [[Gustav Kirchhoff]] and [[Hermann von Helmholtz]] in Berlin. While working with Helmholtz, he experimentally verified an important relationship between the optical and electrical properties of materials. This relationship was seen as a confirmation of Maxwell's theory, of which Helmholtz was a staunch supporter. Boltzmann also made extensive use of the laboratory of a colleague at Ganz, August Toepler | + | In 1869, at age 25, he was appointed full Professor of Mathematical Physics at the [[University of Graz]] in the province of [[Styria]]. In 1869, he spent several months in [[Heidelberg]] working with [[Robert Bunsen]] and [[Leo Königsberger]] and then in 1871, he was with [[Gustav Kirchhoff]] and [[Hermann von Helmholtz]] in Berlin. While working with Helmholtz, he experimentally verified an important relationship between the optical and electrical properties of materials. This relationship was seen as a confirmation of Maxwell's theory, of which Helmholtz was a staunch supporter. Boltzmann also made extensive use of the laboratory of a colleague at Ganz, [[August Toepler]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1872, Boltzmann, who had been working on his treatment of the kinetic theory, published a paper that took into consideration the dimensions of molecules in its calculations. In this paper, entitled "Further studies on the thermal equilibrium among gas molecules," he for the first time wrote an equation representing the mathematical conditions that must be satisfied by a function representing the velocity distribution among molecules in motion. It is today referred to as the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, since Maxwell had derived a similar equation. By applying this equation, Boltzmann could explain the properties of heat conduction, diffusion and viscosity in gases. In the same year, using his equations, he attempted to explain the second law of thermodynamics in terms of the kinetic theory of gases. His final expression of this thesis is called the H theorem. | |

| − | In 1873 Boltzmann joined the [[University of Vienna]] as Professor of Mathematics | + | ===Controversy over Boltzmann's theories=== |

| + | Loschmidt later objected to Boltzmann's findings because it basically showed that an irreversible process is the result of a reversible process, which violates conservation of energy. He also noted that Boltzmann's work did not take into consideration the effect of a gravitational field on the kinetic theory. Boltzmann defended his work, saying that the apparent contradiction is due to the statistical probabilities involved. In his later papers he worked out the gravitational effects on a gas. | ||

| + | |||

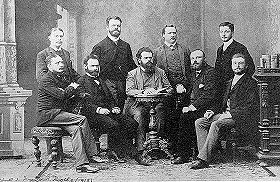

| + | In 1873, Boltzmann joined the [[University of Vienna]] as Professor of Mathematics, where he stayed until 1876, when he succeeded Toepler as director of the Physics institute at Graz, winning the position over [[Ernst Mach]]. Among his students in Graz were [[Svante Arrhenius]] and [[Walther Nernst]]. He spent 14 years in Graz. | ||

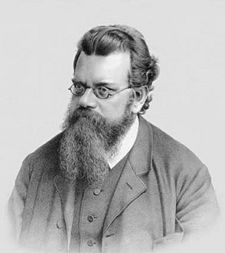

[[Image:Boltzmann-grp.jpg|thumb|left|280px|Ludwig Boltzmann and co-workers in Graz, 1887. (standing, from the left) [[Walther Nernst|Nernst]], Streintz, [[Svante Arrhenius|Arrhenius]], Hiecke, (sitting, from the left) Aulinger, Ettingshausen, Boltzmann, [[Ignacij Klemenčič|Klemenčič]], Hausmanninger.]] | [[Image:Boltzmann-grp.jpg|thumb|left|280px|Ludwig Boltzmann and co-workers in Graz, 1887. (standing, from the left) [[Walther Nernst|Nernst]], Streintz, [[Svante Arrhenius|Arrhenius]], Hiecke, (sitting, from the left) Aulinger, Ettingshausen, Boltzmann, [[Ignacij Klemenčič|Klemenčič]], Hausmanninger.]] | ||

| + | ===Marriage=== | ||

In 1872, long before women were admitted to Austrian universities, Boltzmann met Henriette von Aigentler, an aspiring teacher of mathematics and physics in Graz. She was refused permission to unofficially audit lectures, and Boltzmann advised her to appeal; she did, successfully. She and Boltzmann were married On July 17, 1876; they had three daughters and two sons. | In 1872, long before women were admitted to Austrian universities, Boltzmann met Henriette von Aigentler, an aspiring teacher of mathematics and physics in Graz. She was refused permission to unofficially audit lectures, and Boltzmann advised her to appeal; she did, successfully. She and Boltzmann were married On July 17, 1876; they had three daughters and two sons. | ||

| − | In 1877, Boltzmann tried to further clarify the relationship between probability and the second law of thermodynamics. He introduced an equation that showed the relationship between entropy and probability. Mechanics, he thought, could not account for a complete explanation of the laws of thermodynamics, and he introduced "the measurement of probability." These and similar concepts being explored by J. Willard Gibbs formed the foundation for the field of statistical mechanics | + | In 1877, Boltzmann tried to further clarify the relationship between probability and the second law of thermodynamics. He introduced an equation that showed the relationship between entropy and probability. Mechanics, he thought, could not account for a complete explanation of the laws of thermodynamics, and he introduced "the measurement of probability." These and similar concepts being explored by [[J. Willard Gibbs]] formed the foundation for the field of statistical mechanics. |

| − | |||

| − | + | Between 1880 and 1883, Boltzmann continued to develop his statistical approach and refined a theory to explain [[friction]] and diffusion in gases. | |

| − | Boltzmann was appointed Chair of Theoretical Physics at the [[University of Munich]] in [[Bavaria]], Germany in 1890. In 1893, he succeeded his teacher Joseph Stefan as Professor of Theoretical Physics at the University of Vienna. | + | In 1885, he became member of the Imperial [[Austrian Academy of Sciences]] and in 1887, he became the President of the [[University of Graz]]. It was around this time that Heinrich Hertz discovered the electromagnetic waves predicted by Maxwell. Inspired by this discovery and reminded of his earlier electromagnetic researches, Boltzman devised demonstrations on radio waves and lectured on the topic. In 1889, Boltzmann's eldest son, Ludwig, suffered an attack of [[appendicitis]], from which he died. This was a source of great sorrow to Boltzmann. |

| + | |||

| + | Boltzmann was appointed Chair of Theoretical Physics at the [[University of Munich]] in [[Bavaria]], Germany, in 1890. In 1893, he succeeded his teacher Joseph Stefan as Professor of Theoretical Physics at the University of Vienna. | ||

=== Final years === | === Final years === | ||

| − | + | Boltzman spent much of the next 15 years of his life defending the atomic theory. The scientific community of the time was divided into two camps, one defending the actual existence of atoms, and the other opposing the theory. Boltzmann was a defender of the atomic theory, and in 1894, he attended a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science during which the two different positions were debated. | |

| + | |||

| + | At a meeting in 1895, in Lubeck, another set of views, represented by their respective proponents, were aired. Georg Helm and Wilhelm Ostwald presented their position on ''[[energetics]],'' which saw energy, and not matter, as the chief reality. Boltzmann's position appeared to carry the day among the younger physicists, including a student of [[Max Plank]], who had supported Boltzmann in the debate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Boltzmann did not get along with some of his colleagues in Vienna, particularly [[Ernst Mach]], who became a professor of philosophy and history of sciences in 1895. Thus in 1900, Boltzmann went to the [[University of Leipzig]], on the invitation of [[Wilhelm Ostwald]]. After the retirement of Mach due to poor health, Boltzmann came back to Vienna, in 1902. His students included [[Karl Przibram]], [[Paul Ehrenfest]], and [[Lise Meitner]]. | ||

[[Image:Boltzmann's-molecule.jpg|225px|thumb|right|[[Ludwig Boltzmann|Boltzmann]]’s 1898 I<sub>2</sub> molecule diagram showing atomic “sensitive region” (α, β) overlap.]] | [[Image:Boltzmann's-molecule.jpg|225px|thumb|right|[[Ludwig Boltzmann|Boltzmann]]’s 1898 I<sub>2</sub> molecule diagram showing atomic “sensitive region” (α, β) overlap.]] | ||

| − | In Vienna, Boltzmann not only taught physics but also lectured on philosophy. Boltzmann’s lectures on natural philosophy were very popular | + | ===Boltzmann as lecturer=== |

| + | In Vienna, Boltzmann not only taught physics but also lectured on philosophy. Boltzmann’s lectures on natural philosophy were very popular and received considerable attention. His first lecture was an enormous success. Even though the largest lecture hall had been chosen for it, the audience overflowed the hall. Because of the great successes of Boltzmann’s philosophical lectures, he received invitations from royalty for private audiences. | ||

| − | Boltzmann | + | Boltzmann suffered from a number of infirmities. When he was a student, he often studied in dim candle light, and later blamed this sacrifice for his impaired eyesight, which he endured more or less throughout his career. He also suffered increasingly from [[asthma]], possibly triggered by heart problems, and from intense headaches. |

| − | On September 5, 1906, while on a summer vacation in [[Duino]], near [[Trieste]], Boltzmann committed [[suicide]] | + | On the psychological and spiritual level, Boltzmann was subject to rapid alternation of depressed moods with elevated, expansive, or irritable moods. He himself jestingly attributed his rapid swings in temperament to the fact that he was born during the night between [[Mardi Gras]] and [[Ash Wednesday]]. He had, almost certainly, [[bipolar disorder]].<ref>Washington Post, [http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/books/chap1/lisemeitner.htm Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics]. Retrieved August 24, 2007.</ref> Meitner relates that those who were close to Boltzmann were aware of his bouts of severe depression and his suicide attempts. |

| + | |||

| + | On September 5, 1906, while on a summer vacation with his wife and youngest daughter in [[Duino]], near [[Trieste]], Boltzmann committed [[suicide]] by hanging himself. | ||

== Physics== | == Physics== | ||

Boltzmann's most important scientific contributions were in [[kinetic theory]], including the [[Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution]] for molecular speeds in a gas. In addition, [[Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics]] and the [[Boltzmann distribution]] over energies remain the foundations of [[classical mechanics|classical]] statistical mechanics. They are applicable to the many [[phenomenon|phenomena]] that do not require [[Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics#Limits of applicability|quantum statistics]] and provide a remarkable insight into the meaning of [[thermodynamic temperature|temperature]]. | Boltzmann's most important scientific contributions were in [[kinetic theory]], including the [[Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution]] for molecular speeds in a gas. In addition, [[Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics]] and the [[Boltzmann distribution]] over energies remain the foundations of [[classical mechanics|classical]] statistical mechanics. They are applicable to the many [[phenomenon|phenomena]] that do not require [[Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics#Limits of applicability|quantum statistics]] and provide a remarkable insight into the meaning of [[thermodynamic temperature|temperature]]. | ||

| − | Much of the [[physics]] establishment rejected his thesis about the reality of [[atom]]s and [[molecule]]s | + | Much of the [[physics]] establishment rejected his thesis about the reality of [[atom]]s and [[molecule]]s—a belief shared, however, by [[James Clerk Maxwell|Maxwell]] in [[Scotland]] and [[Josiah Willard Gibbs|Gibbs]] in the [[United States]]; and by most chemists since the discoveries of [[John Dalton]] in 1808. He had a long-running dispute with the editor of the preeminent [[Germany|German]] physics journal of his day, who refused to let Boltzmann refer to atoms and molecules as anything other than convenient constructs. Only a couple of years after Boltzmann's death, [[Jean Baptiste Perrin|Perrin's]] studies of [[colloid]]al suspensions (1908-1909) confirmed the values of [[Avogadro's number]] and Boltzmann's constant, and convinced the world that the tiny particles really exist. |

| − | + | The equation | |

| − | |||

:<math> S = k \, \log W </math> | :<math> S = k \, \log W </math> | ||

| − | + | relating probability to the thermodynamic quantity called entropy is engraved on Boltzmann's [[headstone|tombstone]] at the Vienna [[Zentralfriedhof]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== The Boltzmann equation == | == The Boltzmann equation == | ||

| Line 93: | Line 101: | ||

:<math> \frac{\partial f}{\partial t}+ v \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+ \frac{F}{m} \frac{\partial f}{\partial v} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t}\left.{\!\!\frac{}{}}\right|_\mathrm{collision} </math> | :<math> \frac{\partial f}{\partial t}+ v \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+ \frac{F}{m} \frac{\partial f}{\partial v} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t}\left.{\!\!\frac{}{}}\right|_\mathrm{collision} </math> | ||

| − | where <math>f</math> represents the distribution function of single-particle position and momentum at a given time (see the [[Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution]]), <math>F</math> is a force, <math>m</math> is the mass of a particle, <math>t</math> is the time and | + | where <math>f</math> represents the distribution function of single-particle position and momentum at a given time (see the [[Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution]]), <math>F</math> is a force, <math>m</math> is the mass of a particle, <math>t</math> is the time and <math>v</math> is an average velocity of particles. This equation relates the rates of change of the distribution function with respect to the the variables that define its value |

| − | |||

| − | This equation | ||

[[Image:Zentralfriedhof Vienna - Boltzmann.JPG|thumb|left|200px|Boltzmann's grave in the [[Zentralfriedhof]], Vienna, with bust and entropy formula.]] | [[Image:Zentralfriedhof Vienna - Boltzmann.JPG|thumb|left|200px|Boltzmann's grave in the [[Zentralfriedhof]], Vienna, with bust and entropy formula.]] | ||

| − | In principle, the above equation completely describes the dynamics of an ensemble of gas particles, given appropriate | + | In principle, the above equation completely describes the dynamics of an ensemble of gas particles, given appropriate limiting conditions. It is possible, for example, to calculate the probable distribution of velocities among an ensemble of molecules at a point in time, as well as for one molecule over a stretch of time. The Boltzmann equation is notoriously difficult to solve. [[David Hilbert]] spent years trying to solve it without any real success. |

| − | The form of the collision term assumed by Boltzmann was approximate. However for an [[ideal gas]] the standard | + | The form of the collision term assumed by Boltzmann was approximate. However, for an [[ideal gas]] the standard solution of the Boltzmann equation is highly accurate. |

| − | Boltzmann tried for many years to "prove" the [[second law of thermodynamics]] using his gas-dynamical equation | + | Boltzmann tried for many years to "prove" the [[second law of thermodynamics]] using his gas-dynamical equation—his famous [[H-theorem]]. It was from the probabilistic assumption alone that Boltzmann's success emanated. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Energetics of evolution == | == Energetics of evolution == | ||

| − | Boltzmann's views played an essential role in the development of [[energetics]], the scientific study of energy flows under transformation. In 1922, for example, [[Alfred J. Lotka]] referred to Boltzmann as one of the first proponents of the proposition that available energy, also called [[exergy]], can be understood as the fundamental object under contention in the biological, or life-struggle and therefore also in the evolution of the organic world. | + | Boltzmann's views played an essential role in the development of [[energetics]], the scientific study of energy flows under transformation. In 1922, for example, [[Alfred J. Lotka]] referred to Boltzmann as one of the first proponents of the proposition that available energy, also called [[exergy]], can be understood as the fundamental object under contention in the biological, or life-struggle and therefore also in the evolution of the organic world. Lotka interpreted Boltzmann's view to imply that available energy could be the central concept that unified physics and biology as a quantitative physical principle of evolution. In the forward to Boltzmann's ''Theoretical Physics and Philosophical Problems,'' S.R. de Groot noted that |

| − | + | <blockquote>Boltzmann had a tremendous admiration for Darwin and he wished to extend Darwinism from biological to cultural evolution. In fact he considered biological and cultural evolution as one and the same things. … In short, cultural evolution was a physical process taking place in the brain. Boltzmann included ethics in the ideas which developed in this fashion … | |

| + | </blockquote> | ||

[[Howard T. Odum]] later sought to develop these views when looking at the evolution of ecological systems, and suggested that the [[maximum power principle]] was an example of Darwin's law of [[natural selection]]. | [[Howard T. Odum]] later sought to develop these views when looking at the evolution of ecological systems, and suggested that the [[maximum power principle]] was an example of Darwin's law of [[natural selection]]. | ||

| − | == | + | == Stefan-Boltzmann law == |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The rate at at which energy radiates from a hot body is proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature. This law was established experimentally by by Jožef Stefan in 1879. Boltzmann, who was Stefan's student, successfully derived the law from theoretical considerations in 1884. | |

| − | == | + | == Legacy == |

| − | + | Boltzmann refined the mathematics originally applied by James Clerk Maxwell to develop the kinetic theory of gases. In this he made great progress, and the body of work he left was extended by scientists searching for mathematical techniques to express what became known as quantum mechanics. In Boltzmann's personal life, he was subject to bouts of depression, which he may have repressed by keeping an arduous work schedule. This is what perhaps led to the mental instability that resulted in his suicide. Others have said that it was due to the attacks he received as a proponent of the atomic theory. These attacks may have opened up doubts in his own mind, as some of the best minds challenged aspects of his reasoning. It is the hazard of high-profile achievers that they may stray beyond the reach of their closest friends, and fall prey to the imbalances within their own psyches. Boltzmann's achievements will always be clouded with the tragedy of the circumstances surrounding his death, and the sadness to which his friends were subjected as a result of it. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 139: | Line 131: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | * | + | * Boltzmann, Ludwig. 1964. ''Lectures on Gas Theory''. Berkeley: University of California Press. |

| − | * Brush, Stephen G. | + | * Brush, Stephen G. 1965. ''Kinetic Theory''. Oxford: Pergamon Press. |

| − | + | * Everdell, William R. 1988. The Problem of Continuity and the Origins of Modernism: 1870-1913. ''History of European Ideas'' 9(5): 531-552. | |

| − | * | + | * Gibbs, J. Willard. 1960. ''Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, Developed with Especial Reference to the Rational Foundation of Thermodynamics''. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0918024196 |

| − | + | * Lindley, David. 2001. ''Boltzmann's Atom: The Great Debate that Launched a Revolution in Physics''. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0684851865 | |

| − | + | * Lotka, A. J. 1922. Contribution to the energetics of evolution. ''Proc Nat Acad Sci'' USA 8(6): 147. | |

| − | + | * Tolman, Richard C. 1938. ''The Principles of Statistical Mechanics''. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0486638960 | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 4, 2022. | |

| − | * Ruth Lewin Sime, ''Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics'' [http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/books/chap1/lisemeitner.htm Chapter One: Girlhood in Vienna] gives Lise Meitner's account of Boltzmann's life and career. | + | * Ruth Lewin Sime, ''Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics'' [http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/books/chap1/lisemeitner.htm Chapter One: Girlhood in Vienna] gives Lise Meitner's account of Boltzmann's life and career. |

| − | * | + | * Ali Eftekhari, [http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/archive/00001717/02/Ludwig_Boltzmann.pdf Ludwig Boltzmann (1844 – 1906)]. |

| − | + | * [http://scienceworld.wolfram.com/biography/Boltzmann.html Scienceworld biography]. | |

| − | + | * [https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/1518 Ludwig Boltzmann's Gravesite]. | |

| − | * [http://scienceworld.wolfram.com/biography/Boltzmann.html Scienceworld biography] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Physical sciences]] | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

Latest revision as of 02:38, 5 November 2022

|

Ludwig Boltzmann | |

|---|---|

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann (1844-1906) | |

| Born |

February 20, 1844 |

| Died | September 5, 1906

|

| Residence | |

| Nationality | |

| Field | Physicist |

| Institutions | University of Graz University of Vienna University of Munich University of Leipzig |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Academic advisor | Josef Stefan |

| Notable students | Paul Ehrenfest Philipp Frank |

| Known for | Boltzmann's constant Boltzmann equation Boltzmann distribution Stefan-Boltzmann law |

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann (February 20, 1844 – September 5, 1906) was an Austrian physicist famous for his application of probability theory to the study of molecules in a gas. He used the results of his theoretical investigations to explain the thermodynamic properties of materials. He was one of the most important advocates of the atomic theory when that scientific model was still highly controversial. Other scientists extended his work to express what became known as quantum mechanics. His personal life, however, was clouded with bouts of depression and he ended it with suicide.

Biography

Childhood

Boltzmann was born in Vienna, then capital of the Austrian Empire. He was the eldest of three children of Ludwig Georg Boltzmann, a tax official, and Katarina Pauernfeind of Salzburg. He received his primary education from a private tutor at the home of his parents. Boltzmann attended high school in Linz, Upper Austria. As a youth, his interests encompassed literature, butterfly collecting, and music. For a short time, he studied piano under the famous composer Anton Bruckner. At age 15, Boltzmann lost his father to tuberculosis.

University years

Boltzmann studied physics at the University of Vienna, starting in 1863. Among his teachers were Josef Loschmidt, who was the first to measure the size of a molecule, and Joseph Stefan, who discovered the law by which radiation depends on the temperature of a body. Stefan introduced Boltzmann to Maxwell's work by giving him some of Maxwell's papers on electricity, and an English grammar book to help him learn English. Loschmidt and Stefan, Boltzmann's chief mentors during this period, became his close friends. The laboratory in which they worked, in a private house separate from the university campus, was sparsely equipped. "We always had enough ideas," Boltzmann would later say. "Our only worry was the experimental apparatus."[1] Boltzmann published his first paper, on the electrical resistance between different points on a conducting sphere, in 1865. He received his doctorate in 1866, working under Stefan's supervision.

Early research

In this same year, he published his first paper on the kinetic theory of gases, entitled, "On the mechanical significance of the second law of thermodynamics." In 1867, he became a Privatdozent (lecturer). Boltzmann worked two more years as Stefan’s assistant. The following year, Boltzmann published a paper, "Studies on the equipartition of thermal kinentic energy among material point masses," in which he attempted to express the manner in which energy was distributed among the trillions of molecules in a sample of gas.[2]

Academic career

In 1869, at age 25, he was appointed full Professor of Mathematical Physics at the University of Graz in the province of Styria. In 1869, he spent several months in Heidelberg working with Robert Bunsen and Leo Königsberger and then in 1871, he was with Gustav Kirchhoff and Hermann von Helmholtz in Berlin. While working with Helmholtz, he experimentally verified an important relationship between the optical and electrical properties of materials. This relationship was seen as a confirmation of Maxwell's theory, of which Helmholtz was a staunch supporter. Boltzmann also made extensive use of the laboratory of a colleague at Ganz, August Toepler.

In 1872, Boltzmann, who had been working on his treatment of the kinetic theory, published a paper that took into consideration the dimensions of molecules in its calculations. In this paper, entitled "Further studies on the thermal equilibrium among gas molecules," he for the first time wrote an equation representing the mathematical conditions that must be satisfied by a function representing the velocity distribution among molecules in motion. It is today referred to as the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, since Maxwell had derived a similar equation. By applying this equation, Boltzmann could explain the properties of heat conduction, diffusion and viscosity in gases. In the same year, using his equations, he attempted to explain the second law of thermodynamics in terms of the kinetic theory of gases. His final expression of this thesis is called the H theorem.

Controversy over Boltzmann's theories

Loschmidt later objected to Boltzmann's findings because it basically showed that an irreversible process is the result of a reversible process, which violates conservation of energy. He also noted that Boltzmann's work did not take into consideration the effect of a gravitational field on the kinetic theory. Boltzmann defended his work, saying that the apparent contradiction is due to the statistical probabilities involved. In his later papers he worked out the gravitational effects on a gas.

In 1873, Boltzmann joined the University of Vienna as Professor of Mathematics, where he stayed until 1876, when he succeeded Toepler as director of the Physics institute at Graz, winning the position over Ernst Mach. Among his students in Graz were Svante Arrhenius and Walther Nernst. He spent 14 years in Graz.

Marriage

In 1872, long before women were admitted to Austrian universities, Boltzmann met Henriette von Aigentler, an aspiring teacher of mathematics and physics in Graz. She was refused permission to unofficially audit lectures, and Boltzmann advised her to appeal; she did, successfully. She and Boltzmann were married On July 17, 1876; they had three daughters and two sons.

In 1877, Boltzmann tried to further clarify the relationship between probability and the second law of thermodynamics. He introduced an equation that showed the relationship between entropy and probability. Mechanics, he thought, could not account for a complete explanation of the laws of thermodynamics, and he introduced "the measurement of probability." These and similar concepts being explored by J. Willard Gibbs formed the foundation for the field of statistical mechanics.

Between 1880 and 1883, Boltzmann continued to develop his statistical approach and refined a theory to explain friction and diffusion in gases.

In 1885, he became member of the Imperial Austrian Academy of Sciences and in 1887, he became the President of the University of Graz. It was around this time that Heinrich Hertz discovered the electromagnetic waves predicted by Maxwell. Inspired by this discovery and reminded of his earlier electromagnetic researches, Boltzman devised demonstrations on radio waves and lectured on the topic. In 1889, Boltzmann's eldest son, Ludwig, suffered an attack of appendicitis, from which he died. This was a source of great sorrow to Boltzmann.

Boltzmann was appointed Chair of Theoretical Physics at the University of Munich in Bavaria, Germany, in 1890. In 1893, he succeeded his teacher Joseph Stefan as Professor of Theoretical Physics at the University of Vienna.

Final years

Boltzman spent much of the next 15 years of his life defending the atomic theory. The scientific community of the time was divided into two camps, one defending the actual existence of atoms, and the other opposing the theory. Boltzmann was a defender of the atomic theory, and in 1894, he attended a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science during which the two different positions were debated.

At a meeting in 1895, in Lubeck, another set of views, represented by their respective proponents, were aired. Georg Helm and Wilhelm Ostwald presented their position on energetics, which saw energy, and not matter, as the chief reality. Boltzmann's position appeared to carry the day among the younger physicists, including a student of Max Plank, who had supported Boltzmann in the debate.

Boltzmann did not get along with some of his colleagues in Vienna, particularly Ernst Mach, who became a professor of philosophy and history of sciences in 1895. Thus in 1900, Boltzmann went to the University of Leipzig, on the invitation of Wilhelm Ostwald. After the retirement of Mach due to poor health, Boltzmann came back to Vienna, in 1902. His students included Karl Przibram, Paul Ehrenfest, and Lise Meitner.

Boltzmann as lecturer

In Vienna, Boltzmann not only taught physics but also lectured on philosophy. Boltzmann’s lectures on natural philosophy were very popular and received considerable attention. His first lecture was an enormous success. Even though the largest lecture hall had been chosen for it, the audience overflowed the hall. Because of the great successes of Boltzmann’s philosophical lectures, he received invitations from royalty for private audiences.

Boltzmann suffered from a number of infirmities. When he was a student, he often studied in dim candle light, and later blamed this sacrifice for his impaired eyesight, which he endured more or less throughout his career. He also suffered increasingly from asthma, possibly triggered by heart problems, and from intense headaches.

On the psychological and spiritual level, Boltzmann was subject to rapid alternation of depressed moods with elevated, expansive, or irritable moods. He himself jestingly attributed his rapid swings in temperament to the fact that he was born during the night between Mardi Gras and Ash Wednesday. He had, almost certainly, bipolar disorder.[3] Meitner relates that those who were close to Boltzmann were aware of his bouts of severe depression and his suicide attempts.

On September 5, 1906, while on a summer vacation with his wife and youngest daughter in Duino, near Trieste, Boltzmann committed suicide by hanging himself.

Physics

Boltzmann's most important scientific contributions were in kinetic theory, including the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for molecular speeds in a gas. In addition, Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics and the Boltzmann distribution over energies remain the foundations of classical statistical mechanics. They are applicable to the many phenomena that do not require quantum statistics and provide a remarkable insight into the meaning of temperature.

Much of the physics establishment rejected his thesis about the reality of atoms and molecules—a belief shared, however, by Maxwell in Scotland and Gibbs in the United States; and by most chemists since the discoveries of John Dalton in 1808. He had a long-running dispute with the editor of the preeminent German physics journal of his day, who refused to let Boltzmann refer to atoms and molecules as anything other than convenient constructs. Only a couple of years after Boltzmann's death, Perrin's studies of colloidal suspensions (1908-1909) confirmed the values of Avogadro's number and Boltzmann's constant, and convinced the world that the tiny particles really exist.

The equation

relating probability to the thermodynamic quantity called entropy is engraved on Boltzmann's tombstone at the Vienna Zentralfriedhof.

The Boltzmann equation

The Boltzmann equation was developed to describe the dynamics of an ideal gas.

where represents the distribution function of single-particle position and momentum at a given time (see the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution), is a force, is the mass of a particle, is the time and is an average velocity of particles. This equation relates the rates of change of the distribution function with respect to the the variables that define its value

In principle, the above equation completely describes the dynamics of an ensemble of gas particles, given appropriate limiting conditions. It is possible, for example, to calculate the probable distribution of velocities among an ensemble of molecules at a point in time, as well as for one molecule over a stretch of time. The Boltzmann equation is notoriously difficult to solve. David Hilbert spent years trying to solve it without any real success.

The form of the collision term assumed by Boltzmann was approximate. However, for an ideal gas the standard solution of the Boltzmann equation is highly accurate.

Boltzmann tried for many years to "prove" the second law of thermodynamics using his gas-dynamical equation—his famous H-theorem. It was from the probabilistic assumption alone that Boltzmann's success emanated.

Energetics of evolution

Boltzmann's views played an essential role in the development of energetics, the scientific study of energy flows under transformation. In 1922, for example, Alfred J. Lotka referred to Boltzmann as one of the first proponents of the proposition that available energy, also called exergy, can be understood as the fundamental object under contention in the biological, or life-struggle and therefore also in the evolution of the organic world. Lotka interpreted Boltzmann's view to imply that available energy could be the central concept that unified physics and biology as a quantitative physical principle of evolution. In the forward to Boltzmann's Theoretical Physics and Philosophical Problems, S.R. de Groot noted that

Boltzmann had a tremendous admiration for Darwin and he wished to extend Darwinism from biological to cultural evolution. In fact he considered biological and cultural evolution as one and the same things. … In short, cultural evolution was a physical process taking place in the brain. Boltzmann included ethics in the ideas which developed in this fashion …

Howard T. Odum later sought to develop these views when looking at the evolution of ecological systems, and suggested that the maximum power principle was an example of Darwin's law of natural selection.

Stefan-Boltzmann law

The rate at at which energy radiates from a hot body is proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature. This law was established experimentally by by Jožef Stefan in 1879. Boltzmann, who was Stefan's student, successfully derived the law from theoretical considerations in 1884.

Legacy

Boltzmann refined the mathematics originally applied by James Clerk Maxwell to develop the kinetic theory of gases. In this he made great progress, and the body of work he left was extended by scientists searching for mathematical techniques to express what became known as quantum mechanics. In Boltzmann's personal life, he was subject to bouts of depression, which he may have repressed by keeping an arduous work schedule. This is what perhaps led to the mental instability that resulted in his suicide. Others have said that it was due to the attacks he received as a proponent of the atomic theory. These attacks may have opened up doubts in his own mind, as some of the best minds challenged aspects of his reasoning. It is the hazard of high-profile achievers that they may stray beyond the reach of their closest friends, and fall prey to the imbalances within their own psyches. Boltzmann's achievements will always be clouded with the tragedy of the circumstances surrounding his death, and the sadness to which his friends were subjected as a result of it.

Notes

- ↑ Jagdish Mehra and Helmut Rechenberg, The Historical Development of Quantum Theory (New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001). ISBN 0387906428

- ↑ William R. Everdell, The First Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth-Century Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997). ISBN 0226224805

- ↑ Washington Post, Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boltzmann, Ludwig. 1964. Lectures on Gas Theory. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Brush, Stephen G. 1965. Kinetic Theory. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Everdell, William R. 1988. The Problem of Continuity and the Origins of Modernism: 1870-1913. History of European Ideas 9(5): 531-552.

- Gibbs, J. Willard. 1960. Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, Developed with Especial Reference to the Rational Foundation of Thermodynamics. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0918024196

- Lindley, David. 2001. Boltzmann's Atom: The Great Debate that Launched a Revolution in Physics. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0684851865

- Lotka, A. J. 1922. Contribution to the energetics of evolution. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 8(6): 147.

- Tolman, Richard C. 1938. The Principles of Statistical Mechanics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0486638960

External links

All links retrieved November 4, 2022.

- Ruth Lewin Sime, Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics Chapter One: Girlhood in Vienna gives Lise Meitner's account of Boltzmann's life and career.

- Ali Eftekhari, Ludwig Boltzmann (1844 – 1906).

- Scienceworld biography.

- Ludwig Boltzmann's Gravesite.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.