Difference between revisions of "Loki" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Contracted}}{{Claimed}} | + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Contracted}}{{Claimed}} {{ce}} |

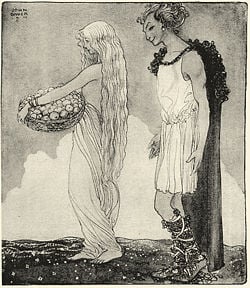

[[Image:Manuscript_loki.jpg|thumb|right|250px|This picture, from an 18th century [[Iceland|Icelandic]] manuscript, shows '''Loki''' with his invention - the fishing net.]] | [[Image:Manuscript_loki.jpg|thumb|right|250px|This picture, from an 18th century [[Iceland|Icelandic]] manuscript, shows '''Loki''' with his invention - the fishing net.]] | ||

Revision as of 18:21, 15 May 2007

Loki (sometimes referred to by his full name (Loki Laufeyjarson)) is the god of mischief, lies and trickery in Norse mythology. He is the son of Fárbauti and Laufey (two giants), and is a blood-brother of Odin. He is described as the "contriver of all fraud" and fulfills the role of trickster among the Aesir, though his eventual involvement in the downfall of the gods at Ragnarök implies a more malevolent nature than such a designation usually signifies. Loki bears many names that reflect his character as a deceiver: "Lie-Smith," "Sly-God," "Shape-Changer," "Sly-One," and "Wizard Of Lies" (among others).

Despite significant scholarly research, Loki seems to have been a figure that roused the imagination more that any religious impulse, as "there is nothing to suggest that Loki was ever worshiped."[1] For this reason, Loki can be seen as less of a "god" and more of a general mythical being. He was not a member of Vanir and is not always counted among the Aesir, the two groupings of Nordic gods. Though some sources do place him among the latter group, this may be due to his close relation with Odin and the amount of time that he spends among them in Asgard (as opposed to among his own kin (the giants)).

Loki in a Norse Context

As a figure in Norse mythology, Loki belonged to a complex religious and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E.[2] The tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to exemplify a unified cultural focus on physical prowess and military might.

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war. In fact, the greatest divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.[3] The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

Loki fulfills the role of trickster among the Aesir, though his eventual involvement in the downfall of the gods at Ragnarök implies a more malevolent nature than such a designation usually signifies.

Characteristics

Loki's role as a deceiver made him the prototypical "con man" in Norse mythology. In many Eddic accounts, he is depicted helping the gods resolve issues (which he was often the cause of in the first place). Some illustrations of this include the myth in which he shears Sif's hair and then replaces it, or the kidnapping of Idunn (which he orchestrated) and her rescue (which he then accomplished).[4] In realizing his multifarious schemes, Loki is aided by his ability to changes his sex and form at will (with some examples of his transmogrification including a salmon, a mare (who eventually gave birth to a monstrous colt), a bird, and a flea).[5] His generally coarse disposition (and his antipathy towards the other Norse Gods) are well attested in the Lokasenna ("The Flyting of Loki"), an intriguing skaldic poem that purports to describe one of Loki's fateful visits to the hall of the Aesir, where he proceeds to insult, mock and defame all of the deities in attendance with unrestrained bile. [6]

Describing the Sly God, the Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson (1178-1241 C.E.) states:

- "Call him Son of Fárbauti and Laufey, ... Father of the Monster of Ván (that is, Fenris-Wolf), and of the Vast Monster (that is, the Midgard Serpent [Jormungandr]), and of Hel...; Kinsman and Uncle, Evil Companion and Benchmate of Odin and the Aesir, ... Thief of the Giants, of the Goat, of Brisinga-men, and of Idunn's apples, Kinsman of Sleipnir [Odin's eight-legged horse that Loki was the mother of], Husband of Sigyn, Foe of the Gods, Harmer of Sif's Hair, Forger of Evil, the Sly God, Slanderer and Cheat of the Gods, Contriver of Balder's death, the Bound God, Wrangling Foe of Heimdall and of Skadi.[7]

These varied titled make reference to Loki's numerous thefts, deceptions and his pre-meditated murder of Odin's son, Balder (discussed below).

Some scholars, noting the intriguing similarities between Odin and Loki (especially in terms of their tendencies to solve problems with cunning, trickery and outright deception), suggest that the two deities may have historically been more closely related than current understandings permit. Ström[8] identifies the two gods to the point of calling Loki "a hypostasis of Odin", and Rübekeil[9] suggests that the two gods were originally identical, deriving from Celtic Lugus (the name of which would be continued in Loki). Regardless of this hypothesis, these undeniable similarities could explain the puzzling fact that Loki is often described as Odin's companion (or even blood brother).[10]

Despite the relatively close ties between Loki and the gods of Asgard, he was still destined to play the "evil" role in the apocalypse (Ragnarök), where he would lead the giants in their final conflict with the Aesir and would be killed in a duel with Heimdall. As Lindow argues, "Loki has a chronological component: He is the enemy of the gods in the far mythic past [due to his lineal connection to the Jotun], and he reverts to this status as the mythic future approaches and arrives. In the mythic present he is ambiguous, "numbered among the aesir."[11]

Mythic Accounts

Family

Loki was the father (and in one instance the mother) of many beasts, humans and monsters.

Together with Angrboda (a giantess), he is said to have had three children:

- Jörmungandr, the sea serpent (destined to slay Thor at Ragnarök);

- Fenrir the giant wolf (preordained to slay Odin at Ragnarök);

- Hel, ruler of the realm of the dead.[12]

In addition to his dalliance with the giantess, Loki is said to have married a goddess named Sigyn who bore him two sons: Narfi and Vali.[13] Finally, while he was in the form of a mare, Loki had congress with a stallion and gave birth to Sleipnir, the eight-legged steed of Odin.[14]

Scheming with fellow gods

As is often the case with trickster figures, Loki is not always a liability to the Aesir, in that he occasionally uses his trickery to aid them in their pursuits. For example, he once tricked an unnamed Jotun (giant) who built the walls around Asgard out of being paid for his work by disguising himself as a mare and leading his horse away from the city. In another myth, he pits the dwarves against each other in a gifting contest, leading them to construct some of the most precious treasures of the Aesir (including Odin's spear, Freyr's airship and Sif's golden wig). Finally, in Þrymskviða, Loki manages, with Thor at his side, to retrieve Mjolnir (the thunder god's hammer) after the giant Þrymr secretly steals it.[15] In all of these cases, Loki's ambiguous status is maintained - though he is Jotun-borne and destined to turn against them, he is an also efficacious and fundamentally useful ally.

Slayer of Balder

The most famous tale of Loki's trickery, and also the point where he becomes truly malevolent, can be seen in the murder of Balder (the Norse god of warmth, goodness and spring). In it, Loki (whether motivated by envy or simple malice) decides that he wishes to end the beloved Balder's life. However, Frigg (Balder's mother), having had premonitions of this dire event, had already spoken to every animate and inanimate object in the world and convinced them not to harm her son.

However, by virtue of his cunning, Loki was able to discover the single item that had escaped the concerned mother's notice: mistletoe. So, he proceeded to take the small plant and fashion it, using his magical abilities, into a potentially deadly arrow. Next, he convinced Hod (Balder's blind brother) to fire the missile, which embedded itself in the joyful god's heart and killed him instantly. When Hod discovered the evil that he had been party to, he fled Asgard into the woods, never to be seen again. Loki, on the other hand, was captured and sentenced to a torturous fate (described below).[16]

The binding of Loki and his fate at Ragnarök

The murder of Balder was not left unpunished, and eventually the gods tracked down Loki, who was hiding in a pool at the base of Franang's Falls in the shape of a salmon. They also hunted down Loki's two children (with Sigyn), Narfi and Váli. His accusers transformed young Váli into a wolf, who immediately turned upon his brother and tore out his throat. The unforgiving Aesir then took the innards of Loki's son and used them to bind Loki to three slabs of stone on the underside of the world. Skaði then suspended an enormous snake over the trickster god's head, so that its venom would drip down upon his prone body. Though Sigyn, his long-suffering wife, sat beside him and collected the venom in a wooden bowl, she still had to empty the bowl whenever it filled up. During those times, the searing venom would drip into the Sly God's face and eyes, causing a pain so terrible that his writhing would shake the entire world. He was sentenced to endure this torment until the coming of Ragnarök.[17]

At the end of time, Loki will be freed by the trembling earth, and will sail to Vigridr (the field where the final conflict will take place) from the north on a ship that will also bear Hel and all the forsaken souls from her realm. Once on the battlefield, he will meet Heimdall, and neither of the two will survive the encounter.[18]

Loki in Popular Culture

The composer Richard Wagner presented Loki under an invented Germanized name Loge in his opera Das Rheingold—Loge is also mentioned, but does not appear as a character, in Die Walküre and Götterdämmerung. The name comes from the common mistranslation and confusion with Logi (a fire-giant), which has created the misconception of Loki being a creation of fire, having hair of fire or being associated with fire, like the Devil in Christianity.

In more modern contexts, Loki (as a character or archetype) is frequently featured in comic books, novels and video games. In these sources, the characterizations vary wildly, from villainous and malicious trickster to benevolent yet mischievous hero.[19]

Notes

- ↑ Turville-Petre, 126.

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.

- ↑ Lindow, 217.

- ↑ See Turville-Petre, 126-146, and Lindow, 216-220, for some examples.

- ↑ Orchard, 236-237.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Skáldskaparmál (XVI), (Brodeur, 114).

- ↑ Folke Ström, Loki. Ein mythologisches Problem, Göteborg (1956)

- ↑ Ludwi Rübekeil, Wodan und andere forschungsgeschichtliche Leichen: exhumiert, Beiträge zur Namenforschung 38 (2003), 25–42

- ↑ Lindow, 219.

- ↑ Lindow, 219. The phrase "numbered among the aesir" is a reference to Snorri's Prose Edda, which describes Loki's relationship to the remainder of the pantheon in those ambiguous terms.

- ↑ Orchard, 237.

- ↑ Orchard, 237. Note: This Vali is not to be confused with Odin's son with the giantess Rind.

- ↑ Turville-Petre, 135-137.

- ↑ See Turville-Petre, 126-146, and Lindow, 216-220, for references to these tales.

- ↑ Munch, 80-86.

- ↑ Munch, 92-94.

- ↑ Dumézil, 61; Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning (LI), (Brodeur, 77-80).

- ↑ See Wikipedia for an "up-to-date" list of such references.

Bibliography

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- Sturlson, Snorri. The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology. Introduced by Sigurdur Nordal; Selected and translated by Jean I. Young. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1954. ISBN 0-520-01231-3.

- Snorri Sturluson. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964.

External links

- Viktor Rydberg's "Teutonic Mythology: Gods and Goddesses of the Northland" e-book

- W. Wagner's "Asgard and the Home of the Gods" e-book

- H. A. Guerber's "Myths of Northern Lands" e-book

- Peter Andreas Munch's "Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes" e-book

- Loki - A Paean in Progress

- An essay on Loki

- More images of Loki

- The Lokasenna - "Loki's Wrangling": an insult competition between Loki and the other gods

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.