Difference between revisions of "Lee De Forest" - New World Encyclopedia

Peter Duveen (talk | contribs) |

Peter Duveen (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

De Forest's patent for the ''responder'' was challenged, however, by another inventor, Reginald Fessenden, who claimed priority. The litigation that followed was decided in favor of De Forest in 1906. | De Forest's patent for the ''responder'' was challenged, however, by another inventor, Reginald Fessenden, who claimed priority. The litigation that followed was decided in favor of De Forest in 1906. | ||

| − | Although De Forest's company managed to sell 90 radio stations, disillusioned stockholders forced De Forest and White to liquidate the company in 1906. But in the same year, De Forest patented what he called the ''audion'', but what is now called a triode, and which proved to be a major advance in radio technology. In 1904, | + | Although De Forest's company managed to sell 90 radio stations, disillusioned stockholders forced De Forest and White to liquidate the company in 1906. But in the same year, De Forest patented what he called the ''audion'', but what is now called a triode, and which proved to be a major advance in radio technology. In 1904, John Ambrose Flemming had patented a diode, which consisted of an anode and a cathode in a vacuum tube. De Forest's tube placed a grid between the anode and cathode which regulated the current flow. The new tube could be used as an amplifier, in much the way as the responder was, although with much greater control and sensitivity. |

| + | |||

| + | Marconi, who bought out Fleming's patent, sued De Forest, and De Forest in turn sued Fleming. Each won their respective suits on different grounds. | ||

Based on this new invention, De Forest established the De Forest Radio Telephone Company in 1907 with White, his former business partner. With great vigor, he began voice broadcasts that featured the latest songs on phonograph records transmitted from his studio in downtown New York City. De Forest also began to invite singers into his studio for live broadcasts. In 1908, he staged a well-publicized broadcast from the Effel Tower in Paris. | Based on this new invention, De Forest established the De Forest Radio Telephone Company in 1907 with White, his former business partner. With great vigor, he began voice broadcasts that featured the latest songs on phonograph records transmitted from his studio in downtown New York City. De Forest also began to invite singers into his studio for live broadcasts. In 1908, he staged a well-publicized broadcast from the Effel Tower in Paris. | ||

| − | Around this time, White engaged in a corporate manipulation that basically robbed the value of De Forest's and other shareholder's investement and concentrated it in a new company. De Forest managed to keep control of his | + | Around this time, White engaged in a corporate manipulation that basically robbed the value of De Forest's and other shareholder's investement and concentrated it in a new company. De Forest managed to keep control of his patents, however, and attempted to bolster its finances through new stock sales of his own. In the meantime, in 1910, he staged a live broadcast of a performance of the opera Cavalleria Rusticana from the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. These successive broadcasting extravaganzas brought De Forest much publicity, and kept his company in the public eye. |

| − | |||

==Middle years== | ==Middle years== | ||

Revision as of 09:36, 21 June 2007

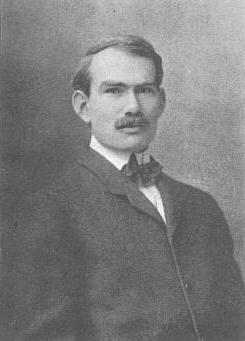

| Lee De Forest | |

De Forest patented the Audion,

a three-electrode tube. | |

| Born | August 26, 1873 |

|---|---|

| Died | June 30, 1961 Hollywood, California |

| Occupation | inventor |

Lee De Forest, (August 26, 1873 – June 30, 1961) was an American inventor with over 300 patents to his credit. De Forest invented the Audion, a vacuum tube that takes relatively weak electrical signals and amplifies them. De Forest is one of the fathers of the "electronic age," as the Audion helped to usher in the widespread use of electronics.

He was involved in several patent lawsuits and he spent a fortune from his inventions on the legal bills. He had four marriages and several failed companies, he was defrauded by business partners, and he was once indicted for mail fraud, but was later acquitted.

He was a charter member of the Institute of Radio Engineers, one of the two predecessors of the IEEE (the other was the American Institute of Electrical Engineers).

Early years

Lee De Forest was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa to Henry Swift DeForest and Anna Robbins. His father was a Congregational minister who hoped that his son would become a minister also. He accepted the position of President of Talladega College in Talladega, Alabama, a school established after the American Civil War to educate African Americans who were no longer under the bondage of slavery. Most citizens resented his father's efforts. Nevertheless, Lee De Forest had several friends among the African American children of the town.

During this time, De Forest spent time in the local library absorbing information from patent applications and otherwise indulging his fascination with machinery of all kinds.

De Forest went to Mount Hermon School to prepare for college. In the summer of 1893, after graduation, he managed to get a job shuttling people in and out of the Great Hall at the Columbia Exhibition in Chicago. This enabled him to visit the many displays of machinery there. In the fall of that year, he entered the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale University. As an inquisitive inventor, he tapped into the electrical system at Yale one evening and completely blacked out the campus, leading to his suspension. However, he was eventually allowed to complete his studies. He paid some of his tuition with income from mechanical and gaming inventions, and he received his Bachelor's degree in 1896. He remained at Yale for graduate studies, and earned his Ph.D. in 1899 with a doctoral dissertation on radio waves.

De Forest tried to obtain employment with Marconi and Tesla, but failed on both accounts. He traveled to Chicago to take a job at Western Electric, and then to Milwaukee, where he worked for the American Wireless Telegraph Company, which was satisfied enough with his work to grant him a raise.

During this period, De Forest invented an improvement to a device called a coherer, basically a tube filled with iron filings which coalesced in the presence of radio waves and conducted electricity. This device had to be constantly reset. De Forest had the idea of using a liquid electrolyte for the same purpose, since it wouldn't require resetting. He called his invention a responder. Inspired by his progress, De Forest rushed to the east coast to cover the yacht race off Sandy Hook, N.J. Due to mutual interference of their transmitters, none of the wireless reportage was successful, but some of the news services that had contracted De Forest publicized the news as delivered by wireless anyway. This attracted the attention of Abraham White, an entrepreneur, who with De Forest established the American De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company.

De Forest's patent for the responder was challenged, however, by another inventor, Reginald Fessenden, who claimed priority. The litigation that followed was decided in favor of De Forest in 1906.

Although De Forest's company managed to sell 90 radio stations, disillusioned stockholders forced De Forest and White to liquidate the company in 1906. But in the same year, De Forest patented what he called the audion, but what is now called a triode, and which proved to be a major advance in radio technology. In 1904, John Ambrose Flemming had patented a diode, which consisted of an anode and a cathode in a vacuum tube. De Forest's tube placed a grid between the anode and cathode which regulated the current flow. The new tube could be used as an amplifier, in much the way as the responder was, although with much greater control and sensitivity.

Marconi, who bought out Fleming's patent, sued De Forest, and De Forest in turn sued Fleming. Each won their respective suits on different grounds.

Based on this new invention, De Forest established the De Forest Radio Telephone Company in 1907 with White, his former business partner. With great vigor, he began voice broadcasts that featured the latest songs on phonograph records transmitted from his studio in downtown New York City. De Forest also began to invite singers into his studio for live broadcasts. In 1908, he staged a well-publicized broadcast from the Effel Tower in Paris.

Around this time, White engaged in a corporate manipulation that basically robbed the value of De Forest's and other shareholder's investement and concentrated it in a new company. De Forest managed to keep control of his patents, however, and attempted to bolster its finances through new stock sales of his own. In the meantime, in 1910, he staged a live broadcast of a performance of the opera Cavalleria Rusticana from the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. These successive broadcasting extravaganzas brought De Forest much publicity, and kept his company in the public eye.

Middle years

The United States Attorney General sued De Forest for fraud (in 1913) on behalf of his shareholders, but he was acquitted. Nearly bankrupt with legal bills, De Forest sold his triode vacuum-tube patent to AT&T and the Bell System in 1913 for the bargain price of $50,000.

De Forest filed another patent in 1916 that became the cause of a contentious lawsuit with the prolific inventor Edwin Howard Armstrong, whose patent for the regenerative circuit had been issued in 1914. The lawsuit lasted twelve years, winding its way through the appeals process and ending up before the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of De Forest.

In 1916, De Forest, from 2XG, broadcast the first radio advertisements (for his own products) and the first Presidential election report by radio in November 1916 for Hughes and Woodrow Wilson. A few months later, de Forest moved his tube transmitter to High Bridge, New York, where one of the most publicized pre-WWI broadcasting events took place. Just like Pittsburgh’s KDKA four years later in 1920, de Forest used the presidential election returns for his broadcast. The New York American installed a private wire and bulletins were sent out every hour. About 2000 listeners heard The Star-Spangled Banner and other anthems, songs, and hymns. DeForest went on to lead radio broadcasts of music (featuring opera star Enrico Caruso) and many other events, but he received little financial backing.

In 1919, De Forest filed the first patent on his sound-on-film process, which improved on the work of Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt, and called it the De Forest Phonofilm process. It recorded sound directly onto film as parallel lines. These lines photographically recorded electrical waveforms from a microphone, which were translated back into sound waves when the movie was projected. This system, which synchronized sound directly onto film, was used to record stage performances (such as in vaudeville), speeches, and musical acts. De Forest established his De Forest Phonofilm Corporation, but he could interest no one in Hollywood in his invention at that time.

De Forest premiered 18 short films made in Phonofilm on 15 April 1923 at the Rivoli Theater in New York City. He was forced to show his films in independent theaters such as the Rivoli, since the movie studios controlled all major theater chains. De Forest chose to film primarily vaudeville acts, not features, limiting the appeal of his process. Max Fleischer and Dave Fleischer used the Phonofilm process for their Sound Car-Tune series of cartoons — featuring the "Follow the Bouncing Ball" gimmick — starting in May 1924. De Forest also worked with Theodore Case, using Case's patents to perfect the Phonofilm system. However, the two men had a falling out, and Case took his patents to studio head William Fox, owner of Fox Film Corporation, who then perfected the Fox Movietone process. Shortly before the Phonofilm Company filed for bankruptcy in September 1926, Hollywood introduced a different method for the "talkies," the sound-on-disc process used by Warner Brothers as Vitaphone.

Eventually Hollywood came back to the sound-on-film methods De Forest had originally proposed, such as Fox Movietone and RCA Photophone. A theater chain owner, M. B. Schlesinger, acquired the UK rights to Phonofilm and released short films of British music hall performers from September 1926 to May 1929. Almost 200 short films were made in the Phonofilm process, and many are preserved in the collections of the Library of Congress and the British Film Institute. Today, many sources such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica list De Forest as one of the inventors of sound film.

Later years

De Forest sold one of his radio manufacturing firms to RCA in 1931. In 1934, the courts sided with De Forest against Edwin Armstrong.

For De Forest's initially rejected, but later adopted, movie soundtrack method, he was given an Academy Award (Oscar) in 1959/1960 for "his pioneering inventions which brought sound to the motion picture," and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

De Forest received the IRE Medal of Honor in 1922, in "recognition for his invention of the three-electrode amplifier and his other contributions to radio." In 1946, he received the Edison Medal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers 'For the profound technical and social consequences of the grid-controlled vacuum tube which he had introduced'.

An important annual medal awarded to engineers by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers is named the Lee De Forest Medal.

De Forest was the guest celebrity on the May 22, 1957 episode of the television show This Is Your Life, where he was introduced as the "Father Of Radio and the Grandfather of Television."

De Forest suffered from a heart ailment in his last years, and this, plus a bladder infection, finally overwhelmed him.

He died in Hollywood in 1961 and was interred in San Fernando Mission Cemetery in Los Angeles, California.

Marriages

Lee de Forest had four wives:

- Lucille Sheardown in February, 1906. They divorced the same year they were married.

- Nora Blatch (1883–?) in February, 1907. They had a daughter, Harriet, but by 1911 they divorced.

- Mary Mayo (1892–?) in December, 1912. In 1920 they were living with their daughter Deena (Eleanor) DeForest (1919-?).

- Marie Mosquini (1899–1983) in October, 1930. She was a silent film actress.

Politics

De Forest was a conservative Republican and fervent anti-communist and anti-fascist. In 1932 he had voted for Franklin Roosevelt, in the midst of the Great Depression, but later came to resent him and his statist policies called him American's "first Fascist president." In 1949, he "sent letters to all members of Congress urging them to vote against socialized medicine, federally subsidized housing, and an excess profits tax." In 1952, he wrote newly elected Vice President Richard Nixon, urging him to "prosecute with renewed vigor your valiant fight to put out Communism from every branch of our government." In December 1953, he cancelled his subscription to The Nation, accusing it of being "lousy with Treason, crawling with Communism."[1]

Quotes

De Forest was given to expansive predictions, many of which were not borne out, but he also made many correct predictions, including microwave communication and cooking.

- "I foresee great refinements in the field of short-pulse microwave signaling, whereby several simultaneous programs may occupy the same channel, in sequence, with incredibly swift electronic communication. Short waves will be generally used in the kitchen for roasting and baking, almost instantaneously" – 1952 [2]

- "While theoretically and technically television may be feasible, commercially and financially it is an impossibility." – 1926[3]

- "To place a man in a multi-stage rocket and project him into the controlling gravitational field of the moon where the passengers can make scientific observations, perhaps land alive, and then return to earth—all that constitutes a wild dream worthy of Jules Verne. I am bold enough to say that such a man-made voyage will never occur regardless of all future advances." – 1926[4]

- "I do not foresee 'spaceships' to the moon or Mars. Mortals must live and die on Earth or within its atmosphere!" – 1952[2]

- "The transistor will more and more supplement, but never supplant, the Audion. Its frequency limitations, a few hundred kilocycles [kilohertz], and its strict power limitations will never permit its general replacement of the Audion amplifier." – 1952[2]

Trivia

Lee De Forest's great nephew, actor Calvert DeForest, became well known in another broadcasting venue some 75 years following his uncle's Audion invention. Calvert DeForest portrayed the comic "Larry 'Bud' Melman" character on David Letterman's late night television programs for two decades.

See also

- Lee De Forest in the 1900 US Census in the Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Lee De Forest in the 1920 US Census in the Bronx, New York

Notes

- ↑ James A. Hijya, Lee De Forest and the Fatherhood of Radio (1992), Lehigh University Press, pages 119-120

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Dawn of the Electronic Age," Popular Mechanics, January, 1952 (linked below)

- ↑ Wikiquote: Incorrect predictions (television)

- ↑ Wikiquote: Incorrect predictions (space travel)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hijiya, James A. 1992. Lee De Forest and the Fatherhood of Radio. Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh University Press. ISBN 0934223238.

- Froehlich, Fritz E., and Allen Kent, eds. 1999. The Froehlich/Kent Encyclopedia of Telecommunications. New York: M. Dekker. ISBN 082472903

- Barnouw, Erik. 1978. A Tower In Babel: A History of Broadcasting in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195004744.

External links

Patents

Patent images in TIFF format

- U.S. Patent 1214283 (PDF) "Wireless Signaling Device" (directional antenna), filed December 1902, issued January 1904

- U.S. Patent 0824637 (PDF) "Oscillation Responsive Device" (vacuum tube detector diode), filed January 1906, issued June 1906

- U.S. Patent 0827523 (PDF) "Wireless Telegraph System" (separate transmitting and receiving antennas), filed December 1905, issued July 1906

- U.S. Patent 0827524 (PDF) "Wireless Telegraph System," filed January 1906 issued July 1906

- U.S. Patent 0836070 (PDF) "Oscillation Responsive Device" (vacuum tube detector - no grid), filed May 1906, issued November 1906

- U.S. Patent 0841386 (PDF) "Wireless Telegraphy" (tunable vacuum tube detector - no grid), filed August 1906, issued January 1907

- U.S. Patent 0876165 (PDF) "Wireless Telegraph Transmitting System" (antenna coupler), filed May 1904, issued January 1908

- U.S. Patent 0879532 (PDF) "Space Telegraphy" (increased sensitivity detector - clearly shows grid), filed January 1907, issued February 18, 1908

- U.S. Patent 0926933 (PDF) "Wireless Telegraphy"

- U.S. Patent 0926934 (PDF) "Wireless Telegraph Tuning Device"

- U.S. Patent 0926935 (PDF) "Wireless Telegraph Transmitter," filed February 1906, issued July 1909

- U.S. Patent 0926936 (PDF) "Space Telegraphy"

- U.S. Patent 0926937 (PDF) "Space Telephony"

- U.S. Patent 0979275 (PDF) "Oscillation Responsive Device" (parallel plates in Bunsen flame) filed February 1905, issued December 1910

- U.S. Patent 1101533 (PDF) "Wireless Telegraphy" (directional antenna/direction finder), filed June 1906, issued June 1914

- U.S. Patent 1214283 (PDF) "Wireless Telegraphy"

Other sites

- Stephen Greene's Who said Lee de Forest was the "Father of Radio"?

- deforestradio.com Dr. Lee De Forest internet radio project & forum

- IEEE History Center

- National Inventors Hall of Fame's Lee De Forest

- Complete Lee De Forest

- Eugenii Katz's Lee De Forest

- Cole, A. B., "Practical Pointers on the Audion: Sales Manager - De Forest Radio Tel. & Tel. Co.," QST, March, 1916, pages 41-44:

- Hong, Sungook, "A History of the Regeneration Circuit: From Invention to Patent Litigation" University, Seoul, Korea (PDF)

- PBS, "Monkeys"; a film on the Audion operation (QuickTime movie)

- Dawn of the Electronic Age: a 1952 Popular Mechanics article written by De Forest about the past, present and future of electronics.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.