Difference between revisions of "Kangyur" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) (Restructuring) |

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

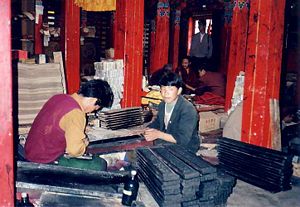

[[Image:Woodblock printing, Sera, 1993.JPG|thumb|right|300px|[[Woodblock printing]] of scriptures. [[Sera Monastery]], Tibet. 1993.]] | [[Image:Woodblock printing, Sera, 1993.JPG|thumb|right|300px|[[Woodblock printing]] of scriptures. [[Sera Monastery]], Tibet. 1993.]] | ||

| − | The '''Kangyur''' (also known as '''Kanjur''') (meaning, "The Translation of the Word") is one of the two major divisions of the [[Tibetan Buddhism|Tibetan Buddhist]] canon along with the '''Tengyur''' ('''Tanjur''') (meaning, "Translation of Treatises"). The formalization of these two divisions was | + | The '''Kangyur''' (also known as '''Kanjur''') (meaning, "The Translation of the Word") is one of the two major divisions of the [[Tibetan Buddhism|Tibetan Buddhist]] canon along with the '''Tengyur''' ('''Tanjur''') (meaning, "Translation of Treatises"). The formalization of these two divisions was completed in the 14th century by Bu-ston (1290–1364). |

| − | The Tibetan | + | The canon of Tibetan Buddhism consists of a loosely defined list of [[Scripture|sacred text]]s recognized by various sects of [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. In addition to sutrayana texts from [[Early Buddhism|Early Buddhist]] (mostly [[Sarvastivada]]) and [[Mahayana]] sources, the canon includes [[Vajrayana|tantric]] texts. However, the distinction between sutra and tantra is not rigid. For example, in some editions the tantra section includes the [[Heart Sutra]]<ref>Conze, ''The Prajnaparamita Literature'', Mouton, the Hague, 1960, page 72.</ref> and even versions of texts in the [[Pali Canon]] such as the ''Mahasutras.''<ref>Peter Skilling, ''Mahasutras'', volume I, 1994, [[Pali Text Society]][http://www.palitext.com], Lancaster, page xxiv </ref> Additionally, the Tibetan canon includes foundational Buddhist texts from early Buddhist schools, mostly the [[Sarvastivada]], and [[Mahayana]] . |

| − | + | The historical development of the Kangyur was significant because it provided greater written cohesion to the collection of Tibetan texts, which were frequently imported into Tibet by oral transmission. Thus, the Kangyur allowed the various Tibetan Buddhist schools to better define accepted scriptures for the tradition. | |

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | + | The first use of the term Kangyur is not known. Collections of canonical Buddhist texts existed already in the time of [[Trisong Detsen]], the sixth king of [[Tubo]], in [[Spiti]], who ruled from 755 until 797 C.E. However, it was not until the 14th century when the formalization of the Tibetan canon's two divisions was compiled by by Bu-ston (1290–1364). | |

==Description and Classification== | ==Description and Classification== | ||

The Kangyur is divided into sections on [[Vinaya]], Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, Avatamsaka, Ratnakuta and other sutras (75% [[Mahayana]], 25% [[Nikaya]] / [[Agama (text)|Agama]] or [[Hinayana]]), and [[tantra]]s. When exactly the term Kangyur was first used is not known. Collections of canonical Buddhist texts already existed in the time of [[Trisong Detsen]], the sixth king of [[Tibet]]. | The Kangyur is divided into sections on [[Vinaya]], Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, Avatamsaka, Ratnakuta and other sutras (75% [[Mahayana]], 25% [[Nikaya]] / [[Agama (text)|Agama]] or [[Hinayana]]), and [[tantra]]s. When exactly the term Kangyur was first used is not known. Collections of canonical Buddhist texts already existed in the time of [[Trisong Detsen]], the sixth king of [[Tibet]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Since the Tibetans did not have their own formally arranged Mahayana canon, they devised their own scheme which divided texts into two broad categories: | Since the Tibetans did not have their own formally arranged Mahayana canon, they devised their own scheme which divided texts into two broad categories: | ||

| Line 20: | Line 18: | ||

#[[Tengyur]] ({{bo|w=bstan-'gyur}}) or "Translated Treatises" is the section to which were assigned commentaries, treatises and abhidharma works (both Mahayana and non-Mahayana). The Tengyur contains 3626 texts in 224 Volumes. | #[[Tengyur]] ({{bo|w=bstan-'gyur}}) or "Translated Treatises" is the section to which were assigned commentaries, treatises and abhidharma works (both Mahayana and non-Mahayana). The Tengyur contains 3626 texts in 224 Volumes. | ||

| + | The exact number of texts in the Kangyur is not fixed. Each editor takes responsibility for removing texts he considers spurious or adding new translations. Currently there are about 12 available Kangyurs. These include the Derge, Lhasa, Narthang, Cone, Peking, Urga, Phudrak, and Stog Palace versions, each named after the physical location of its printing or copying in the case of manuscripts editions. In addition some canonical texts have been found in Tabo and Dunhuang which provide earlier exemplars to texts found in the Kangyur. The majority of extant Kangyur editions appear to stem from the so-called Old Narthang Kangyur, though the Phukdrak and Tawang editions are thought to lie outside of that textual lineage. The stemma of the Kangyur have been well researched in particular by [[Helmut Eimer]] and Paul Harrison. | ||

In the Tibetan tradition, some collections of teachings and practices are held in greater secrecy than others. The sutra tradition comprises works said to be derived from the public teachings of the Buddha, and is taught widely and publicly. The esoteric tradition of [[tantra]] is generally only shared in more intimate settings with those students who the teacher feels have the capacity to utilize it well. | In the Tibetan tradition, some collections of teachings and practices are held in greater secrecy than others. The sutra tradition comprises works said to be derived from the public teachings of the Buddha, and is taught widely and publicly. The esoteric tradition of [[tantra]] is generally only shared in more intimate settings with those students who the teacher feels have the capacity to utilize it well. | ||

Revision as of 04:32, 18 September 2008

The Kangyur (also known as Kanjur) (meaning, "The Translation of the Word") is one of the two major divisions of the Tibetan Buddhist canon along with the Tengyur (Tanjur) (meaning, "Translation of Treatises"). The formalization of these two divisions was completed in the 14th century by Bu-ston (1290–1364).

The canon of Tibetan Buddhism consists of a loosely defined list of sacred texts recognized by various sects of Tibetan Buddhism. In addition to sutrayana texts from Early Buddhist (mostly Sarvastivada) and Mahayana sources, the canon includes tantric texts. However, the distinction between sutra and tantra is not rigid. For example, in some editions the tantra section includes the Heart Sutra[1] and even versions of texts in the Pali Canon such as the Mahasutras.[2] Additionally, the Tibetan canon includes foundational Buddhist texts from early Buddhist schools, mostly the Sarvastivada, and Mahayana .

The historical development of the Kangyur was significant because it provided greater written cohesion to the collection of Tibetan texts, which were frequently imported into Tibet by oral transmission. Thus, the Kangyur allowed the various Tibetan Buddhist schools to better define accepted scriptures for the tradition.

History

The first use of the term Kangyur is not known. Collections of canonical Buddhist texts existed already in the time of Trisong Detsen, the sixth king of Tubo, in Spiti, who ruled from 755 until 797 C.E. However, it was not until the 14th century when the formalization of the Tibetan canon's two divisions was compiled by by Bu-ston (1290–1364).

Description and Classification

The Kangyur is divided into sections on Vinaya, Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, Avatamsaka, Ratnakuta and other sutras (75% Mahayana, 25% Nikaya / Agama or Hinayana), and tantras. When exactly the term Kangyur was first used is not known. Collections of canonical Buddhist texts already existed in the time of Trisong Detsen, the sixth king of Tibet.

Since the Tibetans did not have their own formally arranged Mahayana canon, they devised their own scheme which divided texts into two broad categories:

- Kangyur (Wylie: bka'-'gyur) or "Translated Words", consists of works supposed to have been said by the Buddha himself. All texts presumably have a Sanskrit original, although in many cases the Tibetan text was translated from Chinese or other languages.

- Tengyur (Wylie: bstan-'gyur) or "Translated Treatises" is the section to which were assigned commentaries, treatises and abhidharma works (both Mahayana and non-Mahayana). The Tengyur contains 3626 texts in 224 Volumes.

The exact number of texts in the Kangyur is not fixed. Each editor takes responsibility for removing texts he considers spurious or adding new translations. Currently there are about 12 available Kangyurs. These include the Derge, Lhasa, Narthang, Cone, Peking, Urga, Phudrak, and Stog Palace versions, each named after the physical location of its printing or copying in the case of manuscripts editions. In addition some canonical texts have been found in Tabo and Dunhuang which provide earlier exemplars to texts found in the Kangyur. The majority of extant Kangyur editions appear to stem from the so-called Old Narthang Kangyur, though the Phukdrak and Tawang editions are thought to lie outside of that textual lineage. The stemma of the Kangyur have been well researched in particular by Helmut Eimer and Paul Harrison.

In the Tibetan tradition, some collections of teachings and practices are held in greater secrecy than others. The sutra tradition comprises works said to be derived from the public teachings of the Buddha, and is taught widely and publicly. The esoteric tradition of tantra is generally only shared in more intimate settings with those students who the teacher feels have the capacity to utilize it well.

Characteristic Features

Six Scholarly Ornaments

- Aryadeva foremost disciple of Nagarjuna, continued the philosophical school of Madhyamika

- Dharmakirti famed logician, author of the Seven Treatises; student of Dignana's student Ishvarasena; said to have debated famed Hindu scholar Shankara

- Dignaga famed logician

- Vasubandhu, Asanga's brother

- Gunaprabha foremost student of Vasubandhu, known for his work the Vinayasutra

- Sakyaprabha prominent exponent of the Vinaya

Seventeen Great Panditas

References are sometimes made to the Seventeen Great Panditas. This formulation groups the eight listed above with the following nine scholars.

- Atiśa holder of the “mind training” (Tib. lojong) teachings

- Bhavaviveka early expositor of the Svatantrika Madhyamika

- Buddhapalita early expositor of the Prasangika Madhyamika

- Chandrakirti considered the greatest exponent of Prasangika Madhyamika

- Haribhadra commentator on Asanga's Ornament of Clear Realization

- Kamalashila 8th-century author of important texts on meditation

- Shantarakshita abbot of Nalanda, founder of the Yogachara-Madhyamika who helped Padmasambhava establish Buddhism in Tibet

- Shantideva (8th century Indian) author of the Bodhicaryavatara

- Vimuktisena commentator on Asanga's Ornament of Clear Realization

Five traditional topics of study

All four schools of Tibetan Buddhism generally follow a similar curriculum, using the same Indian root texts and commentaries. The further Tibetan commentaries they use differ by school, although since the 19th century appearance of the widely renowned scholars Jamgon Kongtrul and Ju Mipham, Kagyupas and Nyingmapas use many of the same Tibetan commentaries as well. Different schools, however, place emphasis and concentrate attention on different areas.

The exoteric study of Buddhism is generally organized into "Five Topics," listed as follows with the primary Indian source texts for each:

- Abhidharma (Higher Knowledge, Tib. wylie: mdzod)

- Compendium of Higher Knowledge (Abhidharma Samuccaya) by Asanga

- Treasury of Higher Knowledge (Abhidharma Kosha) by Vasubandhu

- Prajna Paramita (Perfection of Wisdom, Tib. wylie: phar-phyin)

- Ornament of Clear Realization (Abhisamaya Alankara) by Maitreya as related to Asanga

- The Way of the Bodhisattva (Bodhicharyavatara, Tib. wylie: sPyod-‘jug) by Shantideva

- Madhyamaka (Middle Way, Tib. wylie: dbu-ma)

- Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way (Mulamadhyamakakarika, Tib. wylie: rTsa dbu-ma) by Nagarjuna

- Four Hundred Verses on the Yogic Deeds of Bodhisattvas (Catuhsataka) by Aryadeva

- Introduction to the Middle Way (Madhyamakavatara,’’ Tib. wylie: ‘’dBu-ma-la ‘Jug-pa) by Chandrakirti

- Ornament of the Middle Way (Madhyamakalamkara) by Shantarakshita

- The Way of the Bodhisattva (Bodhicharyavatara, Tib. wylie: sPyod-‘jug) by Shantideva

- Pramana (Logic, Means of Knowing, Tib. wylie: tshad-ma)

- Treatise on Valid Cognition (Pramanavarttika) by Dharmakirti

- Compendium on Valid Cognition (Pramanasamuccaya) by Dignaga

- Vinaya (Vowed Morality, Tib. wylie: 'dul-ba)

- The Root of the Vinaya (Dülwa Do Tsawa, 'dul-ba mdo rtsa-ba) by the Pandita Gunaprabha

Five treatises of Maitreya

Also of great importance are the "Five Treatises of Maitreya." These texts are said to have been related to Asanga by the Buddha Maitreya, and comprise the heart of the Yogacara (or Cittamatra, "Mind-Only") school of philosophy in which all Tibetan Buddhist scholars are well-versed. They are as follows:

- Ornament for Clear Realization (Abhisamayalankara, Tib. mngon-par rtogs-pa'i rgyan)

- Ornament for the Mahayana Sutras (Mahayanasutralankara, Tib. theg-pa chen-po'i mdo-sde'i rgyan)

- Sublime Continuum of the Mahayana (Mahayanottaratantrashastra, Ratnagotravibhaga, Tib. theg-pa chen-po rgyud-bla-ma'i bstan)

- Distinguishing Phenomena and Pure Being (Dharmadharmatavibhanga, Tib. chos-dang chos-nyid rnam-par 'byed-pa)

- Distinguishing the Middle and the Extremes (Madhyantavibhanga, Tib. dbus-dang mtha' rnam-par 'byed-pa)

A commentary on the Ornament for Clear Realization called Clarifying the Meaning by the Indian scholar Haribhadra is often used, as is one by Vimuktisena.

Esoteric or Tantra tradition

The division used by the Nyingma or Ancient school:

- Three Outer Tantras:

- Kriyayoga

- Charyayoga

- Yogatantra

- Three Inner Tantras, which correspond to the Anuttarayogatantra:

- Mahayoga

- Anuyoga

- Atiyoga (Tib. Dzogchen)

- The practice of Atiyoga is further divided into three classes: Mental SemDe, Spatial LongDe, and Esoteric Instructional MenNgagDe.

The Sarma or New Translation schools of Tibetan Buddhism (Gelug, Sakya, and Kagyu) divide the Tantras into four hierarchical categories, namely,

- Kriyayoga

- Charyayoga

- Yogatantra

- Anuttarayogatantra

- further divided into "mother", "father" and "non-dual" tantras.

Mother Tantra

"The Yoginī Tantras correspond to what later Tibetan commentators termed the "Mother Tantras" (ma rgyud)" (CST, p. 5).

Father Tantra

In the earlier scheme of classification, the "class ... "Yoga Tantras," ... includes tantras such as the Guhyasamāja", later "classified as "Father Tantras" (pha rgyud) ... placed in the ultimate class ... "Unexcelled Yoga tanras" (rnal 'byor bla med kyi rgyud)." (CST, p. 5)

Nondual Tantra or Advaya Class

- Manjushri-nama-samgiti

- Kalachakra Laghutantra

Two Supremes

- Asanga founder of the Yogachara school

- Nagarjuna founder of the Madhyamaka school[3][4][5]

"The Kangyur usually takes up a hundred or a hundred and eight volumes, the Tengyur two hundred and twenty-five, and the two together contain 4,569 works."[6][7]

- Kangyur (Wylie: Bka'-'gyur) or "Translated Words" consists of works in about 108 volumes supposed to have been spoken by the Buddha himself. All texts presumably had a Sanskrit original, although in many cases the Tibetan text was translated from Chinese or other languages.

- Tengyur (Wylie: Bstan-'gyur) or "Translated Treatises" is the section to which were assigned commentaries, treatises and abhidharma works (both Mahayana and non-Mahayana). The Tengyur contains around 3,626 texts in 224 Volumes.

The Kangyur is divided into sections on Vinaya, Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, other sutras (75% Mahayana, 25% Nikayan or Hinayana), and tantras. It includes texts on the Vinaya, monastic discipline, metaphysics, the Tantras, etc.[8] Some describe the prajñāpāramitā philosophy, others extol the virtues of the various Bodhisattvas, while others expound the Trikāya and the Ālaya-Vijñāna doctrines.[9]

The Bon Kangyur

The Tibetan Bon religion also has its canon literature divided into two sections called the Kangyur and Tengyur claimed to have been translated from foreign languages but the number and contents of the collection are not yet fully known. Apparently, Bon began to take on a literary form about the time Buddhism began to enter Tibet. The Bon Kangyur contains the revelations of Shenrab (Wylie: gShen rab, the traditional founder of Bon.[10][11]

Notes

- ↑ Conze, The Prajnaparamita Literature, Mouton, the Hague, 1960, page 72.

- ↑ Peter Skilling, Mahasutras, volume I, 1994, Pali Text Society[1], Lancaster, page xxiv

- ↑ http://www.sakya.org/News%20Letters/Sakya%20Newsletter%20Summer%202007.pdf

- ↑ Kalu Rinpoche, Luminous Mind: The Way of the Buddha. Wisdom Publications,1997. p. 285 http://books.google.com/books?id=eWVgoVByVhcC&pg=PA285&lpg=PA285&dq=%22two+supremes%22+nagarjuna&source=web&ots=g3PMaucUAA&sig=a97JqzX4462vDLLm8gI6nrNvwKA

- ↑ Tashi Deleg! The Padma Samye Ling Bulletin, Enlightened Masters: Arya Asanga

- ↑ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization. (1962). First English edition - translated by J. E. Stapleton Driver (1972). Reprint (1972): Stanford University Press, Stanford, California. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (paper)

- ↑ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization. (1962). First English edition - translated by J. E. Stapleton Driver (1972). Reprint (1972): Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, p. 251. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (paper)

- ↑ Tucci, Giuseppe. The Religions of Tibet. (1970). First English edition, translated by Geoffrey Samuel (1980). Reprint: (1988), University of California Press, p. 259, n. 10. ISBN 0-520-03856-8 (cloth); ISBN 0-520-064348-1 (pbk).

- ↑ Humphries, Christmas. A Popular Dictionary of Buddhism, p. 104. (1962) Arco Publications, London.

- ↑ Tucci, Giuseppe. The Religions of Tibet. (1970). First English edition, translated by Geoffrey Samuel (1980). Reprint: (1988), University of California Press, p. 213. ISBN 0-520-03856-8 (cloth); ISBN 0-520-064348-1 (pbk).

- ↑ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization. (1962). First English edition - translated by J. E. Stapleton Driver (1972). Reprint (1972): Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, pp. 241, 251. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (paper)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Coleman, Graham, ed. 1993. A Handbook of Tibetan Culture. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.. ISBN 1-57062-002-4

- Ringu Tulku. 2006. The Ri-Me Philosophy of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great: A Study of the Buddhist Lineages of Tibet. Distributed in the United States by Random House. ISBN 1590302869 ISBN 9781590302866

- Smith, E. Gene. 2001. Among Tibetan Texts: History and Literature of the Himalayan Plateau. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-179-3

- Wallace, B. Alan. 1993. Tibetan Buddhism From the Ground Up: A Practical Approach for Modern Life. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0861710754 ISBN 978-0861710751

- Yeshe, Lama Thubten. 2001. The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism. Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. ISBN 1-891868-08-X

External links

- The Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- Tibetan Canon Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- Asian Classics Input Project Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- The Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center Digital Library(Tibetan buddhist texts) Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- Lotsawa House Translations of Tibetan Buddhist texts Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- Overview of typical Kagyu shedra curriculum Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- Review of The Sound of Two Hands Clapping: The Education of a Tibetan Buddhist Monk Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- The Kangyur Collection Retrieved September 18, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.