Difference between revisions of "Intelligence test" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (95 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Psychology]] | [[Category:Psychology]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}} |

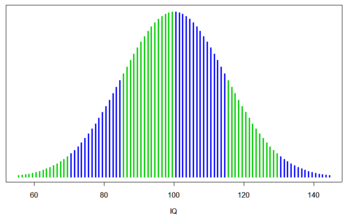

[[Image:IQ_curve.png|thumb|350px|IQ tests are designed to give approximately this Gaussian distribution. Colors delineate one standard deviation. But the true frequency of low and high IQs is greater than that given by the Gaussian curve.]] | [[Image:IQ_curve.png|thumb|350px|IQ tests are designed to give approximately this Gaussian distribution. Colors delineate one standard deviation. But the true frequency of low and high IQs is greater than that given by the Gaussian curve.]] | ||

| − | An '''intelligence quotient''' or '''IQ''' is a score derived from a set of standardized tests of intelligence. Intelligence tests come in many forms | + | An '''intelligence quotient''' or '''IQ''' is a score derived from a set of standardized tests of [[intelligence]]. Intelligence tests come in many forms. Most tests yield both an overall score and individual subtest scores. IQ has been shown to correlate with a number of variables including job performance and socioeconomic advancement, [[health]], longevity, and functional [[literacy]]. However, IQ tests have engendered much controversy and it is important to note that they do not measure all meanings of "intelligence." |

| + | |||

| + | The definition of intelligence has been, and continues to be, subject to debate. Some claim a unitary attribute, often called "general intelligence" or ''g'', which can be measured using standard tests, and which correlates with a person's abilities on a wide range of tasks and contexts. Others have argued that there are multiple "intelligences," with different people displaying differing levels of each type. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Additionally, great controversies have arisen regarding the question of whether this "intelligence," whatever it is that IQ tests measure, is inherited, and if so whether some groups are more intelligent than others. Of particular concern has been the claim that some races are superior, leading justification to [[racism|racist]] expectations and behavior. Despite research and theories from numerous scholars our understanding of intelligence is still limited. Perhaps, since researchers use only their own human intellect to discover the secrets of human intellectual abilities such limitations are to be expected. Viewing ourselves as members of one large human family, each with our own abilities and talents the use of which provide joy to ourselves and to others, allows us to have a deeper appreciation of what "intelligence" means. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | In 1905, the French psychologist Alfred Binet published the first modern | + | In 1905, the French [[psychologist]] [[Alfred Binet]] published the first modern test of [[intelligence]]. His principal goal was to identify students who needed special help in coping with the school [[curriculum]]. Along with his collaborator [[Theodore Simon]], Binet published revisions of his Binet-Simon intelligence scale in 1908 and 1911, the last appearing just before his untimely death. In 1912, the abbreviation of "intelligence quotient" or IQ, a translation of the German ''Intelligenz-quotient'', was coined by the German psychologist [[William Stern]]. |

| − | A further refinement of the Binet-Simon scale was published in 1916 by Lewis M. Terman, from Stanford University, who incorporated Stern's proposal that an individual's intelligence level be measured as an intelligence quotient ( | + | A further refinement of the Binet-Simon scale was published in 1916 by [[Lewis M. Terman]], from [[Stanford University]], who incorporated Stern's proposal that an individual's intelligence level be measured as an intelligence quotient (IQ). Terman's test, which he named the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, formed the basis for one of the modern intelligence tests still commonly used today. |

| − | + | Originally, since it was designed for use with children, IQ was calculated as a ratio with the formula <math>100 \times \frac{\text{mental age}}{\text{chronological age}}.</math> | |

| − | + | For example, a 10-year-old who scored as high as the average 13-year-old would have an IQ of 130 (100*13/10). | |

| − | + | In 1939 [[David Wechsler]] published the first intelligence test explicitly designed for an adult population, the [[Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale]], or WAIS. Since publication of the WAIS, Wechsler extended his scale downward to create the [[Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children]], or WISC. The Wechsler scales contained separate subscores for verbal and performance IQ, thus being less dependent on overall verbal ability than early versions of the Stanford-Binet scale, and was the first intelligence scale to base scores on a standardized [[normal distribution]] rather than an age-based quotient. Since the publication of the WAIS, almost all intelligence scales have adopted the normal distribution method of scoring. | |

| − | + | The use of the normal distribution scoring method makes the term "intelligence quotient" an inaccurate description of the intelligence measurement, but "IQ" is colloquially still used describe all of the intelligence scales currently in use. | |

| − | + | ==IQ testing== | |

| + | ===Structure=== | ||

| + | IQ tests come in many forms. Some tests use a single type of item or question, while others use several different subtests. Those with subtests yield both an overall score and individual subtest scores. | ||

| − | + | A typical IQ test requires the test subject to solve a number of problems in a set time under supervision. Most IQ tests include items from various domains, such as short-term memory, verbal knowledge, spatial visualization, and perceptual speed. Some tests have a total time limit, others have a time limit for each group of problems, and there are a few untimed, unsupervised tests, typically geared to measuring high intelligence. | |

| + | ===Scoring=== | ||

| + | IQ tests are standardized using a representative sample of the population. The tests are calibrated in such a way in order to yield a normal distribution, or "bell curve." Each IQ test, however, is designed and valid only for a certain IQ range. Because so few people score in the extreme ranges, IQ tests usually cannot accurately measure very low and very high IQs. | ||

| − | + | === IQ and general intelligence factor === | |

| − | + | {{main|Intelligence}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Modern IQ tests produce scores for different areas (such as language fluency, three-dimensional thinking, and so forth), with the summary score calculated from subtest scores. The average score, according to the bell curve, is 100. | |

| − | + | Mathematical analysis of individuals' scores on the subtests of a single IQ test or the scores from a variety of different IQ tests ([[Stanford-Binet]], [[WISC-R]], [[Raven's Progressive Matrices]], [[Cattell Culture Fair III]], Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test, Primary Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, and others) reveals that they can be described mathematically as measuring a single common factor plus various factors that are specific to each test. This kind of [[factor analysis]] has led to the theory that underlying these disparate cognitive tasks is a single factor, termed the [[general intelligence factor]] (or ''g''), that corresponds with the common-sense concept of intelligence.<ref>Linda S. Gottfredson, [http://www.psych.utoronto.ca/~reingold/courses/intelligence/cache/1198gottfred.html The General Intelligence Factor]. ''Scientific American,'' 9(4) (1998): 24–29. Retrieved July 31, 2009.</ref> In the normal population, ''g'' and IQ are roughly 90 percent correlated and are often used interchangeably. | |

| − | + | However, not all researchers agree that ''g'' can be treated as a single factor. For example, [[Charles Spearman]], who originally developed the theory of ''g,'' made a distinction between "eductive" and "reproductive" mental abilities. [[Raymond Cattell]] identified "fluid" and "crystallized" intelligence (abbreviated Gf and Gc, respectively) as factors of "general intelligence." Cattell conceived of Gf and Gc as separate though correlated mental abilities which together comprise ''g,'' or "general intelligence." He defined fluid intelligence as the ability to find meaning in confusion and solve new problems, whereas crystallized intelligence is defined as the ability to utilize previously acquired knowledge and experience: | |

| + | <blockquote>It is apparent that one of these powers ... has the 'fluid' quality of being directable to almost any problem. By contrast, the other is invested in particular areas of crystallized skills which can be upset individually without affecting the others.<ref>Raymond B. Cattell, ''Intelligence: Its Structure, Growth, and Action'' (New York, NY: Elsevier Science Pub. Co, 1987, ISBN 0444879226).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Many IQ tests attempt to measure both varieties, with the overall IQ score based on a combination of these two scales. The [[Cattell Culture Fair III|Cattell Culture Fair IQ test]], the [[Raven's Progressive Matrices|Raven Progressive Matrices]], and the performance subscale of the WAIS are measures of Gf. Vocabulary tests and the verbal subscale of the WAIS are considered good measures of Gc. | |

| − | + | ==Positive correlations with IQ== | |

| + | While the study of IQ is sometimes treated as an end unto itself, the original purpose of IQ tests was [[validity (psychometric)|validity]], that is, the degree to which IQ correlates with outcomes such as job performance, social pathologies, or academic achievement. ''Validity'' is the correlation between score (in this case cognitive ability, as measured, typically, by a paper-and-pencil test) and outcome (in this case job performance, as measured by a range of factors including supervisor ratings, promotions, training success, and tenure). Different IQ tests differ in their validity for various outcomes. | ||

| − | + | General intelligence has been shown to play an important role in many valued life outcomes. In addition to academic success, IQ correlates to some degree with job performance, socioeconomic advancement (level of education, occupation, and income), and "social pathology" (adult criminality, [[poverty]], [[unemployment]], dependence on [[welfare]], children outside of marriage). Recent work has demonstrated links between general intelligence and health, longevity, and functional [[literacy]]. Correlations between ''[[g (factor)|g]]'' and life outcomes are pervasive, though IQ does not correlate with subjective self-reports of [[happiness]]. IQ and ''g'' correlate highly with school performance and job performance, less so with occupational prestige, moderately with income, and to a small degree with law-abiding behavior. IQ does not explain the inheritance of economic status and wealth. An additional complication is that an individual's IQ score may or may not be stable over the course of the individual's lifetime.<ref name="Neisser95">Ulrich Neisser, et al. [http://www.gifted.uconn.edu/siegle/research/Correlation/Intelligence.pdf "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns,"] ''American Psychologist'' 51(2) 1996:77-101. Retrieved July 28, 2009. </ref> | |

| − | However, | + | === School performance === |

| + | Children with high scores on tests of intelligence tend to learn more of what is taught in school than their lower-scoring peers. However, successful school learning depends on many personal characteristics other than intelligence, such as [[memory]], persistence, interest in school, and willingness to study. | ||

| − | + | Individual scores on college admission-related tests such as the MCAT, GRE, and LSAT are correlated with scores on tests of intelligence. This is partly due to intelligence test scores predicting years of education. To a smaller extent, they also predict occupational status, and income. This may be connected to the fact that many higher status and higher paid occupations can only be entered through professional schools which base part of their admissions on test scores. | |

| − | == | + | === Job performance === |

| + | IQ tests or IQ scores may be used as part of the hiring process for new personnel, based on the understanding that: | ||

| + | <blockquote>For hiring employees without previous experience in the job the most valid predictor of future performance is general mental ability.<ref name="Schmidt98">F. L. Schmidt and J. E. Hunter, "The Validity and Utility of Selection Methods in Psychology: Practical and Theoretical Implications of 85 Years of Research Findings," ''Psychological Bulletin'' 124 (1998): 262–274.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | However, the validity of this measure depends on the type of job and varies across different studies.<ref name="Hunter84">J. E. Hunter, and R. F. Hunter, "Validity and Utility of Alternative Predictors of Job Performance," ''Psychological Bulletin'' 96 (1984): 72–98.</ref> For example, IQ is related to the "academic tasks" (auditory and linguistic measures, memory tasks, academic achievement levels) and much less related to tasks where even precise hand work ("motor functions") are required.<ref>M. H. Warner, J. Ernst, B. D. Townes, J. Peel, and M. Preston, "Relationships between IQ and Neuropsychological Measures in Neuropsychiatric Populations: Within-laboratory and Cross-cultural Replications using WAIS and WAIS-R," ''Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology,'' 9(5) (Oct 1987): 545-562. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=pubmed&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=3667899&ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVAbstractPlus PubMed link] Retrieved July 31, 2009.</ref> | ||

| − | + | The [[American Psychological Association]]'s 1995 report ''Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns'' states that other individual characteristics such as interpersonal skills, aspects of [[personality]], and so forth, are probably of equal or greater importance in predicting job performance. However, at this point, we do not have equally reliable instruments for measuring them.<ref name="Neisser95" /> | |

| − | === | + | === Income === |

| − | + | Studies have shown a correlation between IQ and income. [[Charles Murray]], coauthor of ''[[The Bell Curve]],'' found that IQ has a substantial effect on income independently of family background.<ref>Charles Murray, ''Income Inequality and IQ'', Washington, DC: The AEI Press, 1998, ISBN 0844770949).</ref>. However, the exact nature of the relationship is disputed. | |

| + | |||

| + | The [[American Psychological Association]]'s report stated that IQ scores account for about one-fourth of the social status variance and one-sixth of the income variance. Statistical controls for parental SES eliminate about a quarter of this predictive power. They concluded that psychometric intelligence appears as only one of a great many factors that influence social outcomes.<ref name="Neisser95" /> Some have suggested that non-IQ factors such as inherited wealth, race, and schooling are more important in determining income than IQ.<ref>Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, "The Inheritance of Inequality," ''The Journal of Economic Perspectives'', 16(3) (August 2002): 3-30(28).</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another view is that the relationship between IQ and income is not linear. One reason why some studies claim that IQ only accounts for a sixth of the variation in income is because many studies are based on young adults (many of whom have not yet completed their education). | ||

| − | + | ==Heritability== | |

| + | The respective roles of [[gene]]s and environmental factors (nature vs. nurture) in determining IQ have been the focus of much controversy. The degree to which genetic variation contributes to observed variation in a trait is measured by a statistic called [[heritability]]. Twin and [[adoption]] studies are commonly used to determine the heritability of a trait. | ||

| − | + | Initially, heritability was studied primarily in children. Such studies found the heritability of IQ to be approximately 0.5; that is, half of the variation in IQ among the children studied was due to variation in their genes. The remaining half was thus due to environmental variation and measurement error. Studies with adults, however, have shown a higher heritability of IQ. The [[American Psychological Association]]'s 1995 task force on "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" concluded that within the white population the heritability of IQ is "around .75."<ref name="Neisser95"/> | |

| − | + | Active genotype-environment correlation, also called the "nature of nurture," is observed for IQ. This phenomenon is measured similarly to heritability; but instead of measuring variation in IQ due to genes, variation in environment due to genes is determined. Results of such studies suggest that the way human beings craft their environment is due in part to genetic influences. | |

| + | |||

| + | ===Environment=== | ||

| + | Environmental factors play a large role in determining IQ in certain situations. [[Malnutrition]] correlates with lower IQ, suggesting that proper nutrition in childhood is critical for [[cognitive development]]. Other research indicates environmental factors such as prenatal exposure to [[toxin]]s, the duration of [[breastfeeding]], and micronutrient deficiency may affect IQ. | ||

===Genetics=== | ===Genetics=== | ||

| − | It is reasonable to expect that genetic influences on traits like IQ should become less important as one gains | + | It is reasonable to expect that genetic influences on traits like IQ should become less important as one gains experience with age. Surprisingly, the opposite occurs. Heritability measures in [[infancy]] are as low as 20 percent, around 40 percent in middle childhood, and as high as 80 percent in adulthood.<ref>Robert Plomin et al., ''Behavioral Genetics in the Postgenomic Era'' (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2003, ISBN 1557989265).</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | ==Group differences== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Among the most controversial issues related to the study of intelligence is the observation that intelligence measures such as IQ scores vary between populations. While there is little scholarly debate about the ''existence'' of some of these differences, the ''reasons'' remain highly controversial within academia and in the public sphere. | ||

| − | + | ===Gender and IQ=== | |

| + | {{main|Sex and intelligence}} | ||

| − | + | [[Gender]] and intelligence research investigates differences in the distributions of [[cognition|cognitive]] skills between men and women. Early work by [[Cyril Burt]]<ref>Cyril L. Burt and R. C. Moore, "The Mental Differences between the Sexes," ''Journal of Experimental Pedagogy'' 1 (1912): 273–284, 355–388.</ref> and [[Lewis Terman]]<ref>Lewis M. Terman. ''The Measurement of Intelligence.'' (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1916)</ref> had found no sex differences in IQ using earlier versions of the tests. When the Stanford-Binet test was revised in the 1940s, preliminary tests yielded a higher average IQ for women; the test was consequently adjusted to give identical averages for men and women.<ref>Quinn McNemar, ''The Revision of the Stanford-Binet Scale'' (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1942).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| + | The picture here is complex. Populations of men and women have been found to differ on average in how well they perform on some of these skill tests, although they do equally well on other tests. For example, women tend to score higher on certain verbal and memory tests, whereas men tend to score higher on spatial tests, particularly mental spatial rotations. While these results are relatively uncontroversial, the question of whether men and women differ on average in ''g'' is a matter of debate. Most studies unambiguously find that men as a population are more varied than women in ''g'' (they have a higher [[variance]] and therefore there are more men than women at the extremes of ability). | ||

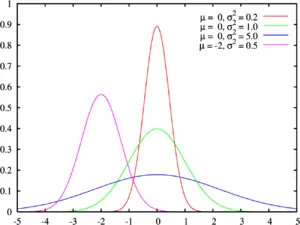

| + | [[Image:Normal distribution pdf.png|thumb|right|300px|Comparing Groups]] | ||

| − | + | The average scores of young men and women in [[mathematics]], for example, will be close, but there will be more men than women in the very low scores and in the very high scores. Thus, in the diagram, the red [[normal distribution|bell curve]] would represent women, compared to the green curve for men.<ref>Camilla Persson Benbow and Julian C Stanley, "Sex Differences in Mathematical Reasoning Ability: More Facts," ''Science'' 222 (1983): 1029-1031.</ref> | |

| − | + | Evidence ''against'' differences in overall average IQ scores between men and women has come from several very large and representative studies.<ref name="Hedges and Nowell">Larry V. Hedges and Amy Nowell, "Sex Differences in Mental Test Scores, Variability, and Numbers of High-Scoring Individuals," ''Science'' 269 (1995):41-45.</ref> However, these studies still found that the scores of men showed greater variance than the scores of women, and that men and women have some differences in average scores on tests of particular abilities, which tend to balance out in overall IQ scores. | |

| − | === | + | ===Race and IQ=== |

| + | {{main|Race and intelligence}} | ||

| + | Theories about the possibility of a relationship between [[race]] and [[intelligence]] have been the subject of speculation and debate since the sixteenth century.<ref>L. E. Andor, (ed.) ''Aptitudes and Abilities of the Black Man in Sub-Saharan Africa: 1784-1963: An Annotated Bibliography.'' (Johannesburg: National Institute for Personnel Research, 1966).</ref><ref>Audrey Smedley and Brian D. Smedley, [http://www.apa.org/journals/releases/amp60116.pdf Race as Biology Is Fiction, Racism as a Social Problem Is Real: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives on the Social Construction of Race]. ''American Psychologist'' 60(1) (2005): 16–26. Retrieved July 31, 2009.</ref> | ||

| − | + | The modern controversy surrounding intelligence and race focuses on the results of IQ studies conducted during the second half of the twentieth century in the [[United States]], Western [[Europe]], and other [[industrialization|industrialized]] nations. Most of the research is based on IQ testing of blacks and whites in the United States, and much of the current debate centers around which environmental factors may influence IQ scores the most, and whether or not there are genetic differences between races that play a significant role in creating the gap, this last question being the most controversial in the debate. | |

| − | + | Those who argue that racial differences in IQ scores can be explained by environmental factors point to a variety of factors that have been shown to influence IQ in children, including: education level, richness of the early home environment, the existence of caste-like minorities, socio-economic factors, culture, [[pidgin]] language barriers, quality of education, [[health]], [[racism]], lack of positive role-models, exposure to [[violence]], sociobiological differences and [[stereotype]] threat. However, there is significant debate about exactly how such environmental factors play their role in creating the gap and the interrelationships between these factors. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Modern theories and research on race and intelligence are often grounded in two controversial assumptions: | |

| + | * that the social categories of [[race]] and [[ethnicity]] are [[concordance (genetics)|concordant]] with [[genetics|genetic]] categories, such as [[biogeographic ancestry]], and | ||

| + | * that intelligence is quantitatively measurable by modern tests and is dominated by a unitary "[[general intelligence factor]]." | ||

| − | = | + | While the general intelligence factor is an accepted and widespread view of ability, still some theorists regard it as misleading.<ref>Stephen J. Ceci, ''On Intelligence more or less: A Bioecological Treatise on Intellectual Development'' (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990, ISBN 0136342051).</ref> There are a wide range of human abilities, including many that seem to have intellectual components which are outside the domain of standard psychometric tests.<ref name="Neisser95"/> |

| + | The more controversial part of the debate is whether group IQ differences are caused in part by genetic differences. [[Hereditarianism]] hypothesizes that a [[inheritance of intelligence|genetic contribution to intelligence]] includes [[gene]]s linked to [[brain]] [[anatomy]] or [[physiology]] that vary by race. The conclusion of some researchers that racial groups in the US vary in average IQ scores in part because of genetic differences between races has led to heated academic debates that have spilled over into the public sphere, drawing a great deal of [[mass media|media]] attention and criticism. | ||

| − | The | + | Observations about race and intelligence also have important applications for critics of the media portrayal of race. Stereotypes in media such as [[literature]], [[music]], [[film]], and [[television]] can reinforce racial stereotypes and may influence the perceived opportunities for success in academics for minority students.<ref>Robert M. Entman and Andrew Rojecki ''The Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in America'' (University Of Chicago Press, 2001, ISBN 0226210766).</ref><ref>John Milton Hoberman, ''Darwin's Athletes: How Sport has Damaged Black America and Preserved the Myth of Race'' (Mariner Books, 1997, ISBN 0395822920).</ref> |

| − | IQ | + | ==Different views on IQ== |

| + | [[Intelligence]] is a concept that has long interested scholars, since it is fundamental to what differentiates [[human being]]s from lower animals. From the originator of the IQ test, [[Alfred Binet]], to contemporary [[psychologist]]s, there has been considerable debate and controversy about the very idea of a [[psychometrics|psychometric]] approach to measuring intelligence. There are various reasons for this, ranging from the problem of standardization, the nature and structure of the test(s), to whether intelligence is actually quantifiable in any meaningful way. However, the greatest controversy over the use of tests of intelligence occurred when results were interpreted as ranking individuals, or groups of individuals, on a unidimensional scale with those achieving high scores regarded as superior to those with lower scores. Still, in some studies, IQ has been found to correlate with job performance, socioeconomic advancement, and other outcomes. Thus, despite continued criticism of the test, uses are still found for IQ. | ||

| − | + | ===Binet=== | |

| + | [[Alfred Binet]] did not believe that IQ test scales were qualified to measure intelligence. He neither invented the term "intelligence quotient" nor supported its numerical expression: | ||

| + | <blockquote>The scale, properly speaking, does not permit the measure of intelligence, because intellectual qualities are not superposable, and therefore cannot be measured as linear surfaces are measured.<ref> Alfred Binet, [http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Binet/binet1.htm "New Methods for the Diagnosis of the Intellectual Level of Subnormals,"] ''L'Année Psychologique'' 12 (1905): 191-244. Retrieved July 31, 2009.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Binet had designed the Binet-Simon intelligence scale in order to identify students who needed special help in coping with the school curriculum. He argued that with proper remedial education programs, most students regardless of background could catch up and perform quite well in school. He did not believe that intelligence was a measurable fixed entity. | |

| − | |||

| + | Binet cautioned: | ||

| + | <blockquote>Some recent thinkers seem to have given their moral support to these deplorable verdicts by affirming that an individual's intelligence is a fixed quantity, a quantity that cannot be increased. We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism; we must try to demonstrate that it is founded on nothing.<ref name=gould/></blockquote> | ||

| − | == | + | ===''The Mismeasure of Man''=== |

| − | + | Some scientists dispute [[psychometrics]] entirely. In ''[[The Mismeasure of Man]]'' [[Stephen Jay Gould]] argued that intelligence tests were based on faulty assumptions and showed their history of being used as the basis for [[scientific racism]].<ref name=gould>Stephen Jay Gould, ''The Mismeasure of Man'' (New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1996, ISBN 0393314251)</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In his books, he criticized the concept of IQ, including a historical discussion of how the IQ tests were created and a technical discussion of why ''g'' is simply a mathematical artifact. Later editions of the book included criticism of ''[[The Bell Curve]].'' | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Gould did not dispute the stability of test scores, nor the fact that they predict certain forms of achievement. He did argue, however, that to base a concept of intelligence on these test scores alone is to ignore many important aspects of mental ability. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | === The view of the American Psychological Association === |

| + | In response to the controversy surrounding Murray and Herrnstein's ''[[The Bell Curve]],'' the [[American Psychological Association]]'s Board of Scientific Affairs established a task force in 1995 to write a consensus statement on the state of intelligence research which could be used by all sides as a basis for discussion. | ||

| − | + | The task force concluded that IQ scores do have high predictive validity for individual differences in school achievement. They confirmed the predictive validity of IQ for adult occupational status, even when variables such as education and family background have been statistically controlled. They agreed that individual (but specifically not population) differences in intelligence are substantially influenced by [[genetics]]. They agreed that there are no significant differences between the average IQ scores of males and females. They reported that there is little evidence to show that childhood diet influences intelligence, except in cases of severe malnutrition. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The task force agreed that large differences do exist between the average IQ scores of populations of different races, and that these differences cannot be attributed to biases in test construction. They suggested that explanations based on [[social status]] and cultural differences are possible, and that environmental factors have raised mean test scores in many populations. They noted that there is not much direct evidence on racial disparities, but what little there is fails to support the genetic hypothesis. Responses to the report included several criticisms that the evidence for partly-genetic explanations had not been adequately examined. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In their report, the representatives of the association regretted that IQ-related works are frequently written with a view to their political consequences: "Research findings were often assessed not so much on their merits or their scientific standing as on their supposed political implications."<ref name="Neisser95"/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | *Baron-Cohen, Simon. "The Extreme-Male-Brain Theory of Autism." In ''Neurodevelopmental Disorders,'' edited by H. Tager-Flusberg. Boston, MA: The MIT Press, 1999. ISBN 026220116X | ||

| + | *Carroll, John B. ''Human Cognitive Abilities: A Survey of Factor-analytical Studies.'' New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0521387124 | ||

| + | *Cattell, Raymond B. ''Intelligence: Its Structure, Growth, and Action.'' New York, NY: Elsevier Science Pub. Co, 1987. ISBN 0444879226 | ||

| + | *Ceci, Stephen J. ''On Intelligence More or Less: A Bioecological Treatise on Intellectual Development.'' Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990. ISBN 0136342051 | ||

| + | *Coward, W. M., and P. R. Sackett. "Linearity of Ability-performance Relationships: A Reconfirmation. ''Journal of Applied Psychology'' 75 (1990): 297–300. | ||

| + | *Duncan, John, P. Burgess, and H. Emslie. "Fluid Intelligence after Frontal Lobe Lesions." ''Neuropsychologia'' 33(3) (1995): 261-268. | ||

| + | *Duncan, John, Rudiger J. Seitz, Jonathan Kolodny, Daniel Bor, Hans Herzog, Ayesha Ahmed, Fiona N. Newell, and Hazel Emslie1. [http://www.hss.caltech.edu/courses/2004-05/winter/psy20/DuncanIQ.pdf "A Neural Basis for General Intelligence."] ''Science'' 289(5478) (2000): 457-460. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Frey, M. C., and D. K. Detterman. "Scholastic Assessment or ''g''? The Relationship Between the Scholastic Assessment Test and General Cognitive Ability." ''Psychological Science'' 15(6) (2003): 373–378. | ||

| + | *Gottfredson, Linda S. [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/1997whygmatters.pdf "Why ''g'' Matters: The Complexity of Everyday Life."] ''Intelligence'' 24(1) (1997): 79–132. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Gottfredson, Linda S. [http://www.psych.utoronto.ca/users/reingold/courses/intelligence/cache/1198gottfred.html "The General Intelligence Factor."] ''Scientific American'' 9(4) (1998): 24–29. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Gottfredson, Linda S. [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/2003suppressingintelligence.pdf "Suppressing Intelligence Research: Hurting those we Intend to Help."] In ''Destructive Trends in Mental Health: The Well-intentioned Path to Harm,'' edited by Roger H. Wright amd Nicholas A. Cummings, 155–186. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis, 2005. ISBN 0415950864 Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Gottfredson, Linda S. [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/2004socialconsequences.pdf "Social consequences of group differences in cognitive ability."] ''(Consequencias sociais das diferencas de grupo em habilidade cognitiva)''." In ''Introdução à psicologia das diferenças individuals,'' edited by C. E. Flores-Mendoza and R. Colom. Porto Alegre, Brazil: ArtMed Publishers. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Gould, Stephen Jay. ''The Mismeasure of Man.'' New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1996. ISBN 0393314251 | ||

| + | *Gray, J. R., C. F. Chabris, and T. S. Braver. [http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/~cfc/Gray2003.pdf "Neural Mechanisms of General Fluid Intelligence."] ''Nature Neuroscience'' 6(3) 2003: 316-322. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Gray, J. R., and P. M. Thompson. [http://www.loni.ucla.edu/~thompson/PDF/nrn0604-GrayThompson.pdf "Neurobiology of Intelligence: Science and Ethics."] ''Neuroscience'' 5(6) 2004: 471-482. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Haier, Richard J., Rex E. Jung, Ronald A. Yeo, Kevin Head, and Michael T. Alkired. [http://www.imaginggenetics.org/PDFs/2005_Haier_NeuroImage_SexdiffIQ.pdf "The Neuroanatomy of General Intelligence: Sex Matters."] ''NeuroImage'' 25 (2005): 320–327. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Harris, Judith R., and Steven Pinker. ''The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn out the Way they Do.'' New York, NY: Free Press. 1998. ISBN 0684857073 | ||

| + | *Hunt, E. "Multiple Views of Multiple Intelligence (Review of ''Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century'')." ''Contemporary Psychology'' 46 (2001):5–7. | ||

| + | *Jensen, Arthur. R. ''Clocking the Mind: Mental Chronometry and Individual Differences.'' Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science, 2006. ISBN 0080449395 | ||

| + | *McClearn, G. E., B. Johansson, S. Berg, N. L. Pedersen, F. Ahern, S. A. Petrill, and R. Plomin. "Substantial Genetic Influence on Cognitive Abilities in Twins 80 or more Years Old." ''Science'' 276 (1997): 1560–1563. | ||

| + | *Murray, Charles, and Richard J. Herrnstein. ''The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life.'' New York, NY: The Free Press, 1994. | ||

| + | *Murray, Charles. [http://www.aei.org/docLib/20040302_book443.pdf ''Income Inequality and IQ.''] Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, AEI Press. 1998. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Neisser, Ulrich, et al. [http://www.gifted.uconn.edu/siegle/research/Correlation/Intelligence.pdf "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns."] ''American Psychologist'' 51(2) 1996:77-101. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Noguera, P. A. [http://www.inmotionmagazine.com/er/pnrp1.html "Racial Politics and the Elusive Quest for Excellence and Equity in Education."] ''In Motion Magazine'' September 30, 2001. Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | *Robert, Plomin, John C. Defries, Ian W. Craig, and Peter McGuffin (eds.). ''Behavioral Genetics in the Postgenomic Era.'' Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2003. ISBN 1557989265 | ||

| + | *Plomin, Robert, John C. DeFries, Gerald E. McClearn, and Peter McGuffin. ''Behavioral Genetics'' 4th ed. New York, NY: Worth Publishers, 2001. ISBN 0716751593 | ||

| + | *Terman, Lewis. ''The Measurement of Intelligence.'' BiblioLife, 2009 (original 1916). ISBN 0559119305 | ||

| + | *Yam, Philip. [http://www.psych.utoronto.ca/users/reingold/courses/intelligence/cache/1198yam.html#link6 Intelligence Considered.] ''Scientific American'' (1998). Retrieved July 28, 2009. | ||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved March 3, 2018. | ||

| + | * [http://www.psychpage.com/learning/library/intell/mainstream.html Mainstream Science on Intelligence] ''Wall Street Journal'' December 13, 1994: A18. | ||

| + | * [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/1997mainstream.pdf Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography.] | ||

| + | * [http://www.iqsociety.org/general/IQchart.pdf IQ comparison chart] | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credits|Intelligence_quotient|176000780}} |

Latest revision as of 12:47, 7 February 2023

An intelligence quotient or IQ is a score derived from a set of standardized tests of intelligence. Intelligence tests come in many forms. Most tests yield both an overall score and individual subtest scores. IQ has been shown to correlate with a number of variables including job performance and socioeconomic advancement, health, longevity, and functional literacy. However, IQ tests have engendered much controversy and it is important to note that they do not measure all meanings of "intelligence."

The definition of intelligence has been, and continues to be, subject to debate. Some claim a unitary attribute, often called "general intelligence" or g, which can be measured using standard tests, and which correlates with a person's abilities on a wide range of tasks and contexts. Others have argued that there are multiple "intelligences," with different people displaying differing levels of each type.

Additionally, great controversies have arisen regarding the question of whether this "intelligence," whatever it is that IQ tests measure, is inherited, and if so whether some groups are more intelligent than others. Of particular concern has been the claim that some races are superior, leading justification to racist expectations and behavior. Despite research and theories from numerous scholars our understanding of intelligence is still limited. Perhaps, since researchers use only their own human intellect to discover the secrets of human intellectual abilities such limitations are to be expected. Viewing ourselves as members of one large human family, each with our own abilities and talents the use of which provide joy to ourselves and to others, allows us to have a deeper appreciation of what "intelligence" means.

History

In 1905, the French psychologist Alfred Binet published the first modern test of intelligence. His principal goal was to identify students who needed special help in coping with the school curriculum. Along with his collaborator Theodore Simon, Binet published revisions of his Binet-Simon intelligence scale in 1908 and 1911, the last appearing just before his untimely death. In 1912, the abbreviation of "intelligence quotient" or IQ, a translation of the German Intelligenz-quotient, was coined by the German psychologist William Stern.

A further refinement of the Binet-Simon scale was published in 1916 by Lewis M. Terman, from Stanford University, who incorporated Stern's proposal that an individual's intelligence level be measured as an intelligence quotient (IQ). Terman's test, which he named the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, formed the basis for one of the modern intelligence tests still commonly used today.

Originally, since it was designed for use with children, IQ was calculated as a ratio with the formula

For example, a 10-year-old who scored as high as the average 13-year-old would have an IQ of 130 (100*13/10).

In 1939 David Wechsler published the first intelligence test explicitly designed for an adult population, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, or WAIS. Since publication of the WAIS, Wechsler extended his scale downward to create the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, or WISC. The Wechsler scales contained separate subscores for verbal and performance IQ, thus being less dependent on overall verbal ability than early versions of the Stanford-Binet scale, and was the first intelligence scale to base scores on a standardized normal distribution rather than an age-based quotient. Since the publication of the WAIS, almost all intelligence scales have adopted the normal distribution method of scoring.

The use of the normal distribution scoring method makes the term "intelligence quotient" an inaccurate description of the intelligence measurement, but "IQ" is colloquially still used describe all of the intelligence scales currently in use.

IQ testing

Structure

IQ tests come in many forms. Some tests use a single type of item or question, while others use several different subtests. Those with subtests yield both an overall score and individual subtest scores.

A typical IQ test requires the test subject to solve a number of problems in a set time under supervision. Most IQ tests include items from various domains, such as short-term memory, verbal knowledge, spatial visualization, and perceptual speed. Some tests have a total time limit, others have a time limit for each group of problems, and there are a few untimed, unsupervised tests, typically geared to measuring high intelligence.

Scoring

IQ tests are standardized using a representative sample of the population. The tests are calibrated in such a way in order to yield a normal distribution, or "bell curve." Each IQ test, however, is designed and valid only for a certain IQ range. Because so few people score in the extreme ranges, IQ tests usually cannot accurately measure very low and very high IQs.

IQ and general intelligence factor

Modern IQ tests produce scores for different areas (such as language fluency, three-dimensional thinking, and so forth), with the summary score calculated from subtest scores. The average score, according to the bell curve, is 100.

Mathematical analysis of individuals' scores on the subtests of a single IQ test or the scores from a variety of different IQ tests (Stanford-Binet, WISC-R, Raven's Progressive Matrices, Cattell Culture Fair III, Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test, Primary Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, and others) reveals that they can be described mathematically as measuring a single common factor plus various factors that are specific to each test. This kind of factor analysis has led to the theory that underlying these disparate cognitive tasks is a single factor, termed the general intelligence factor (or g), that corresponds with the common-sense concept of intelligence.[1] In the normal population, g and IQ are roughly 90 percent correlated and are often used interchangeably.

However, not all researchers agree that g can be treated as a single factor. For example, Charles Spearman, who originally developed the theory of g, made a distinction between "eductive" and "reproductive" mental abilities. Raymond Cattell identified "fluid" and "crystallized" intelligence (abbreviated Gf and Gc, respectively) as factors of "general intelligence." Cattell conceived of Gf and Gc as separate though correlated mental abilities which together comprise g, or "general intelligence." He defined fluid intelligence as the ability to find meaning in confusion and solve new problems, whereas crystallized intelligence is defined as the ability to utilize previously acquired knowledge and experience:

It is apparent that one of these powers ... has the 'fluid' quality of being directable to almost any problem. By contrast, the other is invested in particular areas of crystallized skills which can be upset individually without affecting the others.[2]

Many IQ tests attempt to measure both varieties, with the overall IQ score based on a combination of these two scales. The Cattell Culture Fair IQ test, the Raven Progressive Matrices, and the performance subscale of the WAIS are measures of Gf. Vocabulary tests and the verbal subscale of the WAIS are considered good measures of Gc.

Positive correlations with IQ

While the study of IQ is sometimes treated as an end unto itself, the original purpose of IQ tests was validity, that is, the degree to which IQ correlates with outcomes such as job performance, social pathologies, or academic achievement. Validity is the correlation between score (in this case cognitive ability, as measured, typically, by a paper-and-pencil test) and outcome (in this case job performance, as measured by a range of factors including supervisor ratings, promotions, training success, and tenure). Different IQ tests differ in their validity for various outcomes.

General intelligence has been shown to play an important role in many valued life outcomes. In addition to academic success, IQ correlates to some degree with job performance, socioeconomic advancement (level of education, occupation, and income), and "social pathology" (adult criminality, poverty, unemployment, dependence on welfare, children outside of marriage). Recent work has demonstrated links between general intelligence and health, longevity, and functional literacy. Correlations between g and life outcomes are pervasive, though IQ does not correlate with subjective self-reports of happiness. IQ and g correlate highly with school performance and job performance, less so with occupational prestige, moderately with income, and to a small degree with law-abiding behavior. IQ does not explain the inheritance of economic status and wealth. An additional complication is that an individual's IQ score may or may not be stable over the course of the individual's lifetime.[3]

School performance

Children with high scores on tests of intelligence tend to learn more of what is taught in school than their lower-scoring peers. However, successful school learning depends on many personal characteristics other than intelligence, such as memory, persistence, interest in school, and willingness to study.

Individual scores on college admission-related tests such as the MCAT, GRE, and LSAT are correlated with scores on tests of intelligence. This is partly due to intelligence test scores predicting years of education. To a smaller extent, they also predict occupational status, and income. This may be connected to the fact that many higher status and higher paid occupations can only be entered through professional schools which base part of their admissions on test scores.

Job performance

IQ tests or IQ scores may be used as part of the hiring process for new personnel, based on the understanding that:

For hiring employees without previous experience in the job the most valid predictor of future performance is general mental ability.[4]

However, the validity of this measure depends on the type of job and varies across different studies.[5] For example, IQ is related to the "academic tasks" (auditory and linguistic measures, memory tasks, academic achievement levels) and much less related to tasks where even precise hand work ("motor functions") are required.[6]

The American Psychological Association's 1995 report Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns states that other individual characteristics such as interpersonal skills, aspects of personality, and so forth, are probably of equal or greater importance in predicting job performance. However, at this point, we do not have equally reliable instruments for measuring them.[3]

Income

Studies have shown a correlation between IQ and income. Charles Murray, coauthor of The Bell Curve, found that IQ has a substantial effect on income independently of family background.[7]. However, the exact nature of the relationship is disputed.

The American Psychological Association's report stated that IQ scores account for about one-fourth of the social status variance and one-sixth of the income variance. Statistical controls for parental SES eliminate about a quarter of this predictive power. They concluded that psychometric intelligence appears as only one of a great many factors that influence social outcomes.[3] Some have suggested that non-IQ factors such as inherited wealth, race, and schooling are more important in determining income than IQ.[8]

Another view is that the relationship between IQ and income is not linear. One reason why some studies claim that IQ only accounts for a sixth of the variation in income is because many studies are based on young adults (many of whom have not yet completed their education).

Heritability

The respective roles of genes and environmental factors (nature vs. nurture) in determining IQ have been the focus of much controversy. The degree to which genetic variation contributes to observed variation in a trait is measured by a statistic called heritability. Twin and adoption studies are commonly used to determine the heritability of a trait.

Initially, heritability was studied primarily in children. Such studies found the heritability of IQ to be approximately 0.5; that is, half of the variation in IQ among the children studied was due to variation in their genes. The remaining half was thus due to environmental variation and measurement error. Studies with adults, however, have shown a higher heritability of IQ. The American Psychological Association's 1995 task force on "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" concluded that within the white population the heritability of IQ is "around .75."[3]

Active genotype-environment correlation, also called the "nature of nurture," is observed for IQ. This phenomenon is measured similarly to heritability; but instead of measuring variation in IQ due to genes, variation in environment due to genes is determined. Results of such studies suggest that the way human beings craft their environment is due in part to genetic influences.

Environment

Environmental factors play a large role in determining IQ in certain situations. Malnutrition correlates with lower IQ, suggesting that proper nutrition in childhood is critical for cognitive development. Other research indicates environmental factors such as prenatal exposure to toxins, the duration of breastfeeding, and micronutrient deficiency may affect IQ.

Genetics

It is reasonable to expect that genetic influences on traits like IQ should become less important as one gains experience with age. Surprisingly, the opposite occurs. Heritability measures in infancy are as low as 20 percent, around 40 percent in middle childhood, and as high as 80 percent in adulthood.[9]

Group differences

Among the most controversial issues related to the study of intelligence is the observation that intelligence measures such as IQ scores vary between populations. While there is little scholarly debate about the existence of some of these differences, the reasons remain highly controversial within academia and in the public sphere.

Gender and IQ

Gender and intelligence research investigates differences in the distributions of cognitive skills between men and women. Early work by Cyril Burt[10] and Lewis Terman[11] had found no sex differences in IQ using earlier versions of the tests. When the Stanford-Binet test was revised in the 1940s, preliminary tests yielded a higher average IQ for women; the test was consequently adjusted to give identical averages for men and women.[12]

The picture here is complex. Populations of men and women have been found to differ on average in how well they perform on some of these skill tests, although they do equally well on other tests. For example, women tend to score higher on certain verbal and memory tests, whereas men tend to score higher on spatial tests, particularly mental spatial rotations. While these results are relatively uncontroversial, the question of whether men and women differ on average in g is a matter of debate. Most studies unambiguously find that men as a population are more varied than women in g (they have a higher variance and therefore there are more men than women at the extremes of ability).

The average scores of young men and women in mathematics, for example, will be close, but there will be more men than women in the very low scores and in the very high scores. Thus, in the diagram, the red bell curve would represent women, compared to the green curve for men.[13]

Evidence against differences in overall average IQ scores between men and women has come from several very large and representative studies.[14] However, these studies still found that the scores of men showed greater variance than the scores of women, and that men and women have some differences in average scores on tests of particular abilities, which tend to balance out in overall IQ scores.

Race and IQ

Theories about the possibility of a relationship between race and intelligence have been the subject of speculation and debate since the sixteenth century.[15][16]

The modern controversy surrounding intelligence and race focuses on the results of IQ studies conducted during the second half of the twentieth century in the United States, Western Europe, and other industrialized nations. Most of the research is based on IQ testing of blacks and whites in the United States, and much of the current debate centers around which environmental factors may influence IQ scores the most, and whether or not there are genetic differences between races that play a significant role in creating the gap, this last question being the most controversial in the debate.

Those who argue that racial differences in IQ scores can be explained by environmental factors point to a variety of factors that have been shown to influence IQ in children, including: education level, richness of the early home environment, the existence of caste-like minorities, socio-economic factors, culture, pidgin language barriers, quality of education, health, racism, lack of positive role-models, exposure to violence, sociobiological differences and stereotype threat. However, there is significant debate about exactly how such environmental factors play their role in creating the gap and the interrelationships between these factors.

Modern theories and research on race and intelligence are often grounded in two controversial assumptions:

- that the social categories of race and ethnicity are concordant with genetic categories, such as biogeographic ancestry, and

- that intelligence is quantitatively measurable by modern tests and is dominated by a unitary "general intelligence factor."

While the general intelligence factor is an accepted and widespread view of ability, still some theorists regard it as misleading.[17] There are a wide range of human abilities, including many that seem to have intellectual components which are outside the domain of standard psychometric tests.[3]

The more controversial part of the debate is whether group IQ differences are caused in part by genetic differences. Hereditarianism hypothesizes that a genetic contribution to intelligence includes genes linked to brain anatomy or physiology that vary by race. The conclusion of some researchers that racial groups in the US vary in average IQ scores in part because of genetic differences between races has led to heated academic debates that have spilled over into the public sphere, drawing a great deal of media attention and criticism.

Observations about race and intelligence also have important applications for critics of the media portrayal of race. Stereotypes in media such as literature, music, film, and television can reinforce racial stereotypes and may influence the perceived opportunities for success in academics for minority students.[18][19]

Different views on IQ

Intelligence is a concept that has long interested scholars, since it is fundamental to what differentiates human beings from lower animals. From the originator of the IQ test, Alfred Binet, to contemporary psychologists, there has been considerable debate and controversy about the very idea of a psychometric approach to measuring intelligence. There are various reasons for this, ranging from the problem of standardization, the nature and structure of the test(s), to whether intelligence is actually quantifiable in any meaningful way. However, the greatest controversy over the use of tests of intelligence occurred when results were interpreted as ranking individuals, or groups of individuals, on a unidimensional scale with those achieving high scores regarded as superior to those with lower scores. Still, in some studies, IQ has been found to correlate with job performance, socioeconomic advancement, and other outcomes. Thus, despite continued criticism of the test, uses are still found for IQ.

Binet

Alfred Binet did not believe that IQ test scales were qualified to measure intelligence. He neither invented the term "intelligence quotient" nor supported its numerical expression:

The scale, properly speaking, does not permit the measure of intelligence, because intellectual qualities are not superposable, and therefore cannot be measured as linear surfaces are measured.[20]

Binet had designed the Binet-Simon intelligence scale in order to identify students who needed special help in coping with the school curriculum. He argued that with proper remedial education programs, most students regardless of background could catch up and perform quite well in school. He did not believe that intelligence was a measurable fixed entity.

Binet cautioned:

Some recent thinkers seem to have given their moral support to these deplorable verdicts by affirming that an individual's intelligence is a fixed quantity, a quantity that cannot be increased. We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism; we must try to demonstrate that it is founded on nothing.[21]

The Mismeasure of Man

Some scientists dispute psychometrics entirely. In The Mismeasure of Man Stephen Jay Gould argued that intelligence tests were based on faulty assumptions and showed their history of being used as the basis for scientific racism.[21]

In his books, he criticized the concept of IQ, including a historical discussion of how the IQ tests were created and a technical discussion of why g is simply a mathematical artifact. Later editions of the book included criticism of The Bell Curve.

Gould did not dispute the stability of test scores, nor the fact that they predict certain forms of achievement. He did argue, however, that to base a concept of intelligence on these test scores alone is to ignore many important aspects of mental ability.

The view of the American Psychological Association

In response to the controversy surrounding Murray and Herrnstein's The Bell Curve, the American Psychological Association's Board of Scientific Affairs established a task force in 1995 to write a consensus statement on the state of intelligence research which could be used by all sides as a basis for discussion.

The task force concluded that IQ scores do have high predictive validity for individual differences in school achievement. They confirmed the predictive validity of IQ for adult occupational status, even when variables such as education and family background have been statistically controlled. They agreed that individual (but specifically not population) differences in intelligence are substantially influenced by genetics. They agreed that there are no significant differences between the average IQ scores of males and females. They reported that there is little evidence to show that childhood diet influences intelligence, except in cases of severe malnutrition.

The task force agreed that large differences do exist between the average IQ scores of populations of different races, and that these differences cannot be attributed to biases in test construction. They suggested that explanations based on social status and cultural differences are possible, and that environmental factors have raised mean test scores in many populations. They noted that there is not much direct evidence on racial disparities, but what little there is fails to support the genetic hypothesis. Responses to the report included several criticisms that the evidence for partly-genetic explanations had not been adequately examined.

In their report, the representatives of the association regretted that IQ-related works are frequently written with a view to their political consequences: "Research findings were often assessed not so much on their merits or their scientific standing as on their supposed political implications."[3]

Notes

- ↑ Linda S. Gottfredson, The General Intelligence Factor. Scientific American, 9(4) (1998): 24–29. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ↑ Raymond B. Cattell, Intelligence: Its Structure, Growth, and Action (New York, NY: Elsevier Science Pub. Co, 1987, ISBN 0444879226).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Ulrich Neisser, et al. "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns," American Psychologist 51(2) 1996:77-101. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ↑ F. L. Schmidt and J. E. Hunter, "The Validity and Utility of Selection Methods in Psychology: Practical and Theoretical Implications of 85 Years of Research Findings," Psychological Bulletin 124 (1998): 262–274.

- ↑ J. E. Hunter, and R. F. Hunter, "Validity and Utility of Alternative Predictors of Job Performance," Psychological Bulletin 96 (1984): 72–98.

- ↑ M. H. Warner, J. Ernst, B. D. Townes, J. Peel, and M. Preston, "Relationships between IQ and Neuropsychological Measures in Neuropsychiatric Populations: Within-laboratory and Cross-cultural Replications using WAIS and WAIS-R," Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 9(5) (Oct 1987): 545-562. PubMed link Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ↑ Charles Murray, Income Inequality and IQ, Washington, DC: The AEI Press, 1998, ISBN 0844770949).

- ↑ Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, "The Inheritance of Inequality," The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3) (August 2002): 3-30(28).

- ↑ Robert Plomin et al., Behavioral Genetics in the Postgenomic Era (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2003, ISBN 1557989265).

- ↑ Cyril L. Burt and R. C. Moore, "The Mental Differences between the Sexes," Journal of Experimental Pedagogy 1 (1912): 273–284, 355–388.

- ↑ Lewis M. Terman. The Measurement of Intelligence. (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1916)

- ↑ Quinn McNemar, The Revision of the Stanford-Binet Scale (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1942).

- ↑ Camilla Persson Benbow and Julian C Stanley, "Sex Differences in Mathematical Reasoning Ability: More Facts," Science 222 (1983): 1029-1031.

- ↑ Larry V. Hedges and Amy Nowell, "Sex Differences in Mental Test Scores, Variability, and Numbers of High-Scoring Individuals," Science 269 (1995):41-45.

- ↑ L. E. Andor, (ed.) Aptitudes and Abilities of the Black Man in Sub-Saharan Africa: 1784-1963: An Annotated Bibliography. (Johannesburg: National Institute for Personnel Research, 1966).

- ↑ Audrey Smedley and Brian D. Smedley, Race as Biology Is Fiction, Racism as a Social Problem Is Real: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives on the Social Construction of Race. American Psychologist 60(1) (2005): 16–26. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ↑ Stephen J. Ceci, On Intelligence more or less: A Bioecological Treatise on Intellectual Development (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990, ISBN 0136342051).

- ↑ Robert M. Entman and Andrew Rojecki The Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in America (University Of Chicago Press, 2001, ISBN 0226210766).

- ↑ John Milton Hoberman, Darwin's Athletes: How Sport has Damaged Black America and Preserved the Myth of Race (Mariner Books, 1997, ISBN 0395822920).

- ↑ Alfred Binet, "New Methods for the Diagnosis of the Intellectual Level of Subnormals," L'Année Psychologique 12 (1905): 191-244. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1996, ISBN 0393314251)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baron-Cohen, Simon. "The Extreme-Male-Brain Theory of Autism." In Neurodevelopmental Disorders, edited by H. Tager-Flusberg. Boston, MA: The MIT Press, 1999. ISBN 026220116X

- Carroll, John B. Human Cognitive Abilities: A Survey of Factor-analytical Studies. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0521387124

- Cattell, Raymond B. Intelligence: Its Structure, Growth, and Action. New York, NY: Elsevier Science Pub. Co, 1987. ISBN 0444879226

- Ceci, Stephen J. On Intelligence More or Less: A Bioecological Treatise on Intellectual Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990. ISBN 0136342051

- Coward, W. M., and P. R. Sackett. "Linearity of Ability-performance Relationships: A Reconfirmation. Journal of Applied Psychology 75 (1990): 297–300.

- Duncan, John, P. Burgess, and H. Emslie. "Fluid Intelligence after Frontal Lobe Lesions." Neuropsychologia 33(3) (1995): 261-268.

- Duncan, John, Rudiger J. Seitz, Jonathan Kolodny, Daniel Bor, Hans Herzog, Ayesha Ahmed, Fiona N. Newell, and Hazel Emslie1. "A Neural Basis for General Intelligence." Science 289(5478) (2000): 457-460. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Frey, M. C., and D. K. Detterman. "Scholastic Assessment or g? The Relationship Between the Scholastic Assessment Test and General Cognitive Ability." Psychological Science 15(6) (2003): 373–378.

- Gottfredson, Linda S. "Why g Matters: The Complexity of Everyday Life." Intelligence 24(1) (1997): 79–132. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Gottfredson, Linda S. "The General Intelligence Factor." Scientific American 9(4) (1998): 24–29. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Gottfredson, Linda S. "Suppressing Intelligence Research: Hurting those we Intend to Help." In Destructive Trends in Mental Health: The Well-intentioned Path to Harm, edited by Roger H. Wright amd Nicholas A. Cummings, 155–186. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis, 2005. ISBN 0415950864 Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Gottfredson, Linda S. "Social consequences of group differences in cognitive ability." (Consequencias sociais das diferencas de grupo em habilidade cognitiva)." In Introdução à psicologia das diferenças individuals, edited by C. E. Flores-Mendoza and R. Colom. Porto Alegre, Brazil: ArtMed Publishers. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Gould, Stephen Jay. The Mismeasure of Man. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1996. ISBN 0393314251

- Gray, J. R., C. F. Chabris, and T. S. Braver. "Neural Mechanisms of General Fluid Intelligence." Nature Neuroscience 6(3) 2003: 316-322. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Gray, J. R., and P. M. Thompson. "Neurobiology of Intelligence: Science and Ethics." Neuroscience 5(6) 2004: 471-482. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Haier, Richard J., Rex E. Jung, Ronald A. Yeo, Kevin Head, and Michael T. Alkired. "The Neuroanatomy of General Intelligence: Sex Matters." NeuroImage 25 (2005): 320–327. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Harris, Judith R., and Steven Pinker. The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn out the Way they Do. New York, NY: Free Press. 1998. ISBN 0684857073

- Hunt, E. "Multiple Views of Multiple Intelligence (Review of Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century)." Contemporary Psychology 46 (2001):5–7.

- Jensen, Arthur. R. Clocking the Mind: Mental Chronometry and Individual Differences. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science, 2006. ISBN 0080449395

- McClearn, G. E., B. Johansson, S. Berg, N. L. Pedersen, F. Ahern, S. A. Petrill, and R. Plomin. "Substantial Genetic Influence on Cognitive Abilities in Twins 80 or more Years Old." Science 276 (1997): 1560–1563.

- Murray, Charles, and Richard J. Herrnstein. The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York, NY: The Free Press, 1994.

- Murray, Charles. Income Inequality and IQ. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, AEI Press. 1998. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Neisser, Ulrich, et al. "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns." American Psychologist 51(2) 1996:77-101. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Noguera, P. A. "Racial Politics and the Elusive Quest for Excellence and Equity in Education." In Motion Magazine September 30, 2001. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Robert, Plomin, John C. Defries, Ian W. Craig, and Peter McGuffin (eds.). Behavioral Genetics in the Postgenomic Era. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2003. ISBN 1557989265

- Plomin, Robert, John C. DeFries, Gerald E. McClearn, and Peter McGuffin. Behavioral Genetics 4th ed. New York, NY: Worth Publishers, 2001. ISBN 0716751593

- Terman, Lewis. The Measurement of Intelligence. BiblioLife, 2009 (original 1916). ISBN 0559119305

- Yam, Philip. Intelligence Considered. Scientific American (1998). Retrieved July 28, 2009.

External links

All links retrieved March 3, 2018.

- Mainstream Science on Intelligence Wall Street Journal December 13, 1994: A18.

- Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography.

- IQ comparison chart

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.