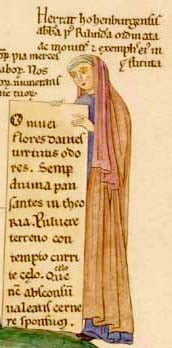

Herrad of Landsberg

Herrad of Landsberg, also Herrade de Landsberg, (c.1130 - July 25 1195) was a twelfth century Alsatian nun and abbess of Hohenburg Abbey in the Vosges mountains. She is known as the author and artist of the pictorial encyclopedia Hortus deliciarum (The Garden of Delights). She was a contemporary of Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), Heloise, (1101-1162), Eleanor of Aquitaine, (1124-1204) and Claire of Assisi, (1194-1253).

Hortus Deliciarum

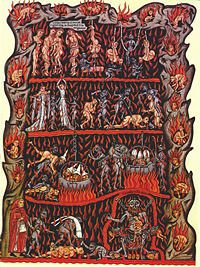

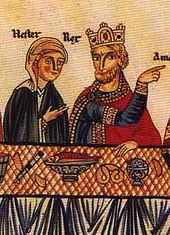

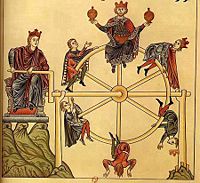

As early as 1165, Herrad had begun within the cloister walls the work for which she is best known, the Hortus Deliciarum, a compendium of all the sciences studied at that time, including theology. In it, Herrad delves into the battle of Virtue and Vice with vivid visual imagery preceding the text. [1] The work, as one would expect from what we know of the literary activity of the twelfth century, while not highly original, shows a wide range of reading. Its chief claim to distinction is the 336 illustrations which adorn the text. Many of these are symbolical representations of theological, philosophical, and literary themes; some are historical, some represent scenes from the actual experience of the artist, and one is a collection of portraits of her sisters in religion. The technique of some of them has been very much admired and in almost every instance they show an artistic imagination which is rare in Herrad's contemporaries. The poetry which accompanies the excerpts from the writers of antiquity and from pagan authors is not the least of Herrad's titles to fame.

It has the defects peculiar to the twelfth century, faults of quantity, words and constructions not sanctioned by classical usage, and peculiar turns of phrase which would hardly pass muster in a school of Latin poetry at the present time. However, the sentiment is sincere, the lines are musical, and above all admirably adapted to the purpose for which they were intended, namely, the service of God by song. Herrad, indeed, tells us that she considers her community to be a congregation gathered together to serve God by singing the divine praises.

Life in the abbey

The image of women during medieval times was very narrow, only two images were available, either the Virgin Mother of Christ or the temptress who seduces men away from God. Wealthy women could expect to be married off for their family's political gain, often dying in childbirth. And sometimes married off again if their aged husband died. There were few opportunities available to women for education because none were allowed into university.

Only a doting father could offer a woman some education or the secluded life in an Abbey. Thus many capable women chose to enter a convent in sacred service to God. Women were often allowed to study and develop their intellect and artistic abilities in the safe environment of the abbey away from the dangers of the "outside world."

The Abbess was often an artist herself, like Hildegard of Bingen, and many were also patrons of the creativity of others. An Abbess could make sure that the nuns were trained in the arts of needlework, manuscript illumination, letters and music as well as their devotional reading.

In the convent life, artists were trained by going through the alphabet, letter by letter. While most work was anonymous, some nuns left little portraits of themselves in their work, or a certain mark to indicate their style. But monastic life encouraged the women to remain humble and simply offer their art to God.

Other contemporary nun artists

There were other nuns of the eleventh and twelfth centuries who were also working on manuscripts. One is Guda, who pictured herself in the initial letter of a work, with the inscription, "Guda, a sinner, wrote and painted this book."

The most famous is abbess extraordinaire Hildegard of Bingen, who wrote three books: the first and most important Scivias ("Know the Way"), in 1151, relating her visions which were largely about "joy," joy in God and in nature, and "in the cosmic egg of creation." Liber vitae meritorum ("Book of Life's Merits"), followed, which dealt with such topics as the forthcoming Apocalypse and Purgatory, which was of special interest in the twelfth century, and anti-abortion (although not equating it with murder). The third was De operatione Dei ("Of God's Activities") also known as Liber divinorum operum ("Book of Divine Works"), her most sophisticated theological work.

Another was, Hitda, whose Gospels of Abbess Hitda of Meschede, seems to have been inspired by contemporary Byzantine paintings. Also, the "Gospels of Abbess Uta", was another early eleventh century artist.

A self-portrait of another, Claricia, (often pictured with a halo above her head) is found in a South German Psalter, c. 1200, which is now in Baltimore, Maryland, at The Walters Art Gallery.

Herrad's contemporary image

Herrad is seen as a pioneer of women. She was one of great artistic ability and thought. In the confines of the abbey many women were free to follow their creativity while participating in monastic life which was not otherwise available to women in that time.

Her sermons sometimes had contemporary themes, one was in realizing the paradoxes of human life. She told the nuns to, "despise the world, despise nothing, despise thyself; despise despising thyself." This theme can be seen in "Superbia" (Pride), a copy of one of her drawings. In her original manuscript, Herrad, sitting on a tiger skin, is seen as leading an army of "female vices" into battle against an army of "female virtues". This work both fascinated and disturbed medieval commentators. [2]

Penelope Johnson highlighted Herrad's contemporary themes in her book, Equal in Monastic Profession: Religious Women in Medieval France, which was researched using monastic documents from more than two dozen nunneries in northern France from the eleventh century to the thirteenth century. She writes about the manner of life for medieval nuns. She opines that the stereotype of passive nuns living in seclusion under monastic rule wasn't the standard but instead "collectively they were empowered by their communal privileges and status to think and act without many of the subordinate attitudes of secular women." An equality of monastic profession was experienced by nuns in the abbey.

The fate of the manuscript

After having been preserved for centuries at the Hohenburg Abbey, the manuscript of Hortus Deliciarum passed into the municipal Library of Strasbourg about the time of the French Revolution. There the miniatures were copied in 1818 by Christian Moritz (or Maurice) Engelhardt; the text was copied and published by Straub and Keller, 1879-1899. Thus, although the original perished in the burning of the Library of Strasbourg during the siege of 1870 in the Franco-Prussian War, we can still form an estimate of the artistic and literary value of Herrad's work, The Garden of Delights.

See also

- Women Artists

- Hildegard of Bingen

- Manuscripts

- List of Hiberno-Saxon illustrated manuscripts

- Abbess Hitda

- Clarisa

- Guda

Notes

- ↑ See Amazon.com's samples of music from Hortus Deliciarum www.amazon.ca Retrieved June, 18, 2008.

- ↑ Lecture notes on Herrad of Landsberg from 'Women Artists: A Historical Survey" by J. J. Wilson and Karen Petersen asstudents.unco.edu Retrieved May 24, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brookes, Barbara, and Dorothy Page, ed. Communities of women: historical perspectives, Dunedin, N.Z.: Otago, 2002. ISBN 1877276316

- Chadwick, Whitney, Women, Art, and Society, Thames and Hudson, London, 1990.

- Eckstein, Lina. Woman under Monasticism: Chapters on Saint-Lore and Convent Life between A.D. 500 and A.D. 1500, Cambridge University Press, 1896. ASIN B000HJTXQQ; Adamant Media Corporation 2005. ISBN 978-0543869180

- Griffiths, Fiona J. The Garden of Delights: Reform and Renaissance for Women in the Twelfth Century (The Middle Ages Series), University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006). ISBN 978-0812239607

- Harris, Ann Sutherland and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists: 1550-1950, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Knopf, New York, 1977. ISBN 978-0394733265

- Johnson, Penelope D. Equal in Monastic Profession: Religious Women in Medieval France (Women in Culture and Society Series), University Of Chicago Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0226401867

- Schmidt, Charles. Herrade of Landsberg, Heitz und Mundel Strasbourg, 1980. ASIN B000IX9AUA

- "Herrad of Landsberg". Catholic Encyclopedia. (1913). New York: Robert Appleton Company. www.newadvent.org Retrieved May 24, 2008.

External Links

Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- Samples of music from Hortus Deliciarum www.amazon.ca'

- Lecture notes on Herrad of Landsberg from 'Women Artists: A Historical Survey" by J. J. Wilson and Karen Petersen asstudents.unco.edu

- Library Glossary of manuscript terms, mostly relating to Western medieval manuscripts prodigi.bl.uk

- Department, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill www/;ob/imc/edu

- for the History of the Book, University of Edinburgh www.hss.ed.ac.uk

- Hortus Deliciarum www2.iath.virginia.edu

- Herrad of Hohenbourg from "Other Women's Voices" home.infionline.net

- Encyclopedia(1913)/Manuscripts en.wikisource.org

This article incorporates text from the public-domain Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.