Gospel of Thomas

| Part of a series on Gnosticism | |

| |

|

History of Gnosticism | |

|

Gnosticism | |

|

Syrian-Egyptic Gnosticism | |

|

Proto-Gnostics | |

|

Fathers of Christian Gnosticism | |

|

Early Gnosticism | |

|

Medieval Gnosticism | |

|

Gnosticism in modern times | |

|

Gnostic texts | |

|

Related articles | |

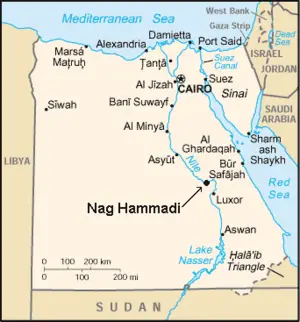

The Gospel of Thomas is an important but long lost work of the New Testament apocyhpa]] completely preserved and rediscovered in a Coptic manuscript discovered in 1945 at Nag Hammadi, Egypt. Unlike the four canonical gospels, which combine narrative accounts of the life of Jesus with sayings, Thomas is a "sayings gospel" with little narrative text, attributed to the apostle Didymus Judas Thomas.

The work begins with the words, "These are the secret sayings which the living Jesus spoke and which Didymus Judas Thomas wrote down. And he said, 'Whoever finds the interpretation of these sayings will not experience death.'"

It comprises 114 sayings attributed to Jesus. Many of these sayings resemble or are identitical to those found in the four canonical Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). Others, however, were unknown until the gospel's discovery, and a few of these run counter to sayings found in the four canonical gospels.

Importance

The Gospel of Thomas is regarded by some as the single most important find in understanding early Christianity outside the New Testament. It offers a window into the worldview of ancient culture, as well as the debates and struggles within the early Christian community. The gospel also assists in understanding early Christianity's relationship, and eventual split, with Judaism.

The Gospel of Thomas is certainly one of the earliest accounts of the teaching of Jesus outside of the canonical gospels, and so is considered a valuable text by biblical scholars of all persuasions. It is unique in that it is ostensibly written from the point of view of Didymus Judas Thomas, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus, and claims to contain special revelations and parables made only to Thomas. It is further unique in that the gospel is no more than a collection of Jesus' sayings and parables, and contains no narrative account of his life, which is something that all four canonical gospels include.

Furthermore, most readers are struck by the fact that this gospel makes no mention of Jesus' resurrection, a crucial point of faith among Christians. Nor does it emphasize the salvific value of Jesus death on the cross and the sacraments of baptism and communion. A minority opinion interprets the opening words of the book, "These are the secret sayings which the living Jesus spoke and which Didymos Judas Thomas wrote down," to mean that the sayings are being presented as the teaching of Jesus Christ after the resurrection, due to the use of the term "living."

Some scholars consider the Gospel of Thomas to be a gnostic text, since it was found in a library among other, more clearly gnostic texts. Yet others reject this interpretation, because Thomas lacks the full-blown mythology of Gnosticism as described by Irenaeus of Lyons (ca. 185) or recognized by modern scholarship. Many consider it a "proto-gnostic" work, affirm the basic gnostic believe that true knowledge of Jesus' teaching enables one to realizes his or her own inner Christhood, but not promoting a formal gnostic cosmology found in later gnostic texts.

No major Christian church accepts this gospel as canonical or authoritative. However, the Jesus Seminar, an association of noted biblical scholars, includes it as the "Fifth Gospel" in its deliberation on the historical Jesus. Virtually all biblical scholars recognize it as an important work for understanding the theoretical Q document, a collection of sayings teachings used by Matthew and Luke but absent from Mark and John. The fact that Thomas is a "sayings Gospel" tends to confirm the theory of Q's existence and has stimulated much discussion on the relationship between Thomas and Q.

Philsophy and theology

The gospel begins, "These are the sayings that the living Jesus spoke and Didymos Judas Thomas recorded." The word "Didymos" (Greek) and "Thomas" (The Aramaic: Tau'ma) both mean "Twin" and may be titles rather than names. Some scholars speculate that he is called the "twin" of Jesus to denote a spiritual unity between the disciple and his master , as referenced in Thomas v. 13, where Jesus says, "I am not your teacher. Because you have drank and become drunk from the very same spring from which I draw."

A central theme of the Gospel of Thomas is that salvation comes through true understanding of the words of Jesus, rather than through faith in his resurrection or partaking in the sacraments of bapitism and holy communion. This, and the fact that it is a "sayings" Gospel with very little discription of the activities of Jesus and no reference to his crucifixion and resurrection, is what distinguishes this gospel from the four canonical gospel.

In the synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke), Jesus is the Messiah who has come to earth to die for our sins that we might be saved through by faith in his resurrection. The Gospel of John, adds that Jesus as a divine heir of the godhead and places particular emphasis on the sacrament of communion. In the Thomas gospel, on the other hand Jesus is primarily a teacher and a spiritual role model. One is not saved by faith in him, but by understanding his teachings and realizing the potential to attain Christhood, just as Jesus did.

The Gospel of Thomas is thus more mystical than the canonical gospels and emphasizes a direct and unmediated experience of the Divine. In Thomas v.108, Jesus says, "Whoever drinks from my mouth will become as I am; I myself shall become that person, and the hidden things will be revealed to him." Furthermore, salvation is found through spiritual-psychological introspection. In Thomas v.70, Jesus says, "If you bring forth what is within you, what you have will save you. If you do not bring it forth, what you do not have within you will kill you." In Thomas v.3, Jesus says, ...the Kingdom of God is within you. This saying also found in Luke 17:21, but in Thomas' gospel it is a consistent an central theme.

Elaine Pagels, one of the pre-eminent scholars of the Gospel of Thomas, argues in her book in her book Beyond Belief that the Gospel of Thomas was widely read in the early church and that portions of both Luke's and John's gospels were designed specifically to refute its viewpoint. She concludes that the Thomas gospel gives us a rare glimpse into the diversity of beliefs in the early Christian community, and a check on what many modern Christians take for granted as being heretical. However the church at large considers the Thomas gospel not as a reflection of "Christian diversity" but as an example of one of the early heresies that attacked the church, namely an early form of Gnosticism.

Relation to other works

When a Coptic version of the complete text of Thomas was found at Nag Hammadi, scholars realized that three separate Greek portions of it had already been discovered in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, in 1898. The manuscripts bearing the Greek fragments of the Gospel of Thomas have been dated to about AD 200, and the manuscript of the Coptic version to about 340. Although the Coptic version is not quite identical to any of the Greek fragments, it is believed that the Coptic version was translated from an earlier Greek version.

The Gospel of Thomas is distinct and unrelated to other apocryphal or pseudepigraphal works, such as the Acts of Thomas or the work called the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, which expands on the canonical texts to describe the miraculous childhood of Jesus. When the Church Father's Hippolytus and Origen (ca. 233) refer to a "Gospel of Thomas" among the heterodox apocryphal gospels, it is unclear whether they mean the Infancy Gospel of Thomas or this "sayings" Gospel of Thomas. Hippolytus may, however, cite logia 4 with reference to the Naassenes in his Refutation of All Heresies 5.7.20, although the literary connection is weak. The Gospel of Thomas is also distinct from the Book of Thomas the Contender, a clearly Gnostic text.

In the 4th century, Cyril of Jerusalem mentioned a "Gospel of Thomas" in his Cathechesis V: "Let none read the gospel according to Thomas, for it is the work, not of one of the twelve apostles, but of one of Mani's three wicked disciples." Very little trace of Manichaean dualism can be detected in this "sayings" Gospel, the Gospel of Thomas, which is agreed to be simpler and less legend-filled than that philosophy.

The text of the Gospel of Thomas has been available to the general public since 1975. It has been translated, published and annotated in several languages. The original version is the property of Egypt's Department of Antiquities. The first photographic edition was published in 1956, and its first critical analysis appeared in 1959.[1]

Date of Composition

There is much debate about when the text was composed, with scholars generally falling into two main camps: an early camp favoring a date prior to the Gospels of Luke and John possibly as early as the mid 50s CE, and a late camp favoring a time after the last of the canonical gospels in the 100s CE.

The early camp

Elaine Pagels, in her book Beyond Belief (2003), argues that both John's and Luke's gospels were written in part to refute the "Thomas Christians" who believed that true followers of Jesus could attain Christhood equal to that of Jesus himself. Pagels interprets the "Doubting Thomas" episode of the Gospel of John as rebuttal of the "Thomas community's de-emphasis on the idea of a physical resurrection, which is nowhere mentioned in the Gospel fo Thomas. In John's gospel, however, Thomas physically touches Jesus and acknowledges the fleshy nature of his resurrected body. This contrast to the docetism of Thomas Christians and later gnostic groups. Likewise, in the Gospel of Luke, the resurrected Jesus goes out of his way to prove that he is not a mere spirit, saying "Look at my hands and my feet. It is I myself! Touch me and see; a ghost does not have flesh and bones, as you see I have." (Luke 24:38) To further prove the physical nature of the resurrection Luke goes so far as to portray Jesus then eating a meal with the disciples, specifying that he ate a broiled fish in their presence.

Some in the "early camp" claim that the Gospel of Thomas is closely related connection to the hypothetical Q document—a collection of sayings found in Matthew and Luke, but absent from the Gospel of Mark.

Other early camp—thos who argue for a date sometime in the 50s—see common themes in Paul's epistles and Thomas absent from the canonical gospels. According to this theory, Paul drew on sayings widely recognized to have come from Jesus, some which are uniquely preserved in the Gospel of Thomas.

The early camp also notes that Thomas reflects very little to none of the full-blown Valentinian gnosticism as seen in many of the other texts in the cache of manuscripts found at Nag Hammadi. It thus represents a kind of proto-gnosticism, reflecting a time when the Christian community had not yet divided between the groups who later became known as gnostic and orthodox Christians.

The late camp

The late camp, on the other hand, dates Thomas sometime after 100, generally in the mid-2nd century. Some argue that Thomas is dependent on the Diatessaron, which was composed shortly after 172. The Greek fragments of Thomas found in Egypt are typically dated between 140 and 200.

Bart D. Ehrman, in Jesus Apocalyptic Prophet of the Millennium, argues that the Jesus of history was a failed apocalyptic preacher, and that his fervent apocalyptic beliefs are recorded in the earliest Christian documents, namely Mark and the authentic Pauline epistles. The earliest Christians believed Jesus would soon return, and their beliefs are echoed in the earliest Christian writings. As the Second Coming did not materialize, later gospels, such as Luke and John, deemphasized an imminent end of the world. Likewise, many sayings in the Gospel of Thomas relate to the imminent end of the world as a profoundly mistaken view, emphasizing that the real Kingdom of God is within the human heart. Such a viewpoint implies a late date as the end of the world and Second Coming never materialized, and the early Christians had to explain Christ's non-appearance.

Another argument put forth by the late camp is an argument from redaction. Under the most commonly accepted solution to the Synoptic problem, Matthew and Luke both used Mark as well as a lost sayings collection called Q to compose their gospels. Sometimes Matthew and Luke modified the wording of their source, Mark (or Q), and the modified text is known as redaction. Proponents of the late camp argue that some of this secondary redaction created by Matthew and Luke shows up in Thomas, which means that Thomas was written after Matthew and Luke were composed. Since Matthew and Luke are generally thought to have been composed in the 80s and 90s, Thomas would have to be composed later than that.

Various other arguments are presented countered by both camps, but are too detailed to present here.

Gospel of Thomas scholars

This is a list of scholars or intellectuals who either have committed significant scholarly work in Gospel of Thomas studies, or have commented on the Gospel.

- Joseph Campbell, mythologist

- Stevan L. Davies, Professor of Religious Studies at College Misericordia and author of The Gospel of Thomas and Christian Wisdom

- April DeConick, Professor of Biblical Studies at Rice University and author of Recovering the Original Gospel of Thomas

- Bart D. Ehrman, author of The New Testament and Other Early Christian Writings (2nd Ed. Oxford University Press, Inc. NY 2004) and The New Testament : A Historical Introduction to Early Christian Writings (3rd Ed. Oxford University Press, Inc. NY 2004).

- Luke Timothy Johnson, Ph.D. Yale, Professor of New Testament, Candler School of Theology, Emory.

- Helmut Koester, Harvard University Divinity professor

- Marvin Meyer, translator of the scholars version SV

- Ronald H. Miller, Associate Professor of Religion at Lake Forest University and author of The Gospel of Thomas: A Guidebook For Spiritual Practice

- Elaine Pagels, author of Gnostic Gospels, Beyond Belief, and The Gnostic Paul: Gnostic Exegesis of the Pauline Epistles

- Stephen Patterson

- Hugh McGregor Ross

- Thin-min Tach, Zen Buddhist

- N. T. Wright, Bishop of Durham and author of the Christian Origins and the People of God series

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Guillaumont, Antoine Jean Baptiste, Henri-Charles Puech, G. Quispel, Walter Curt Till, and Yassah ˁAbd al-Masīh, eds. 1959. Evangelium nach Thomas. Leiden: E. J. Brill Standard edition of the Coptic text

- Johnson, Luke Timothy. The Writings of the New Testament: An Interpretation. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1986. (pp. 530-548.)

- Pagels, Elaine, 2003. Beyond Belief : The Secret Gospel of Thomas (New York: Random House)

- James McConkey Robinson et al., The Nag Hammadi Library in English (4th rev. ed.; Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill, 1996).

External links

- Thomasine Church

- Gospel of Thomas Collection at The Gnosis Archive

- Gospel of St. Thomas - Lost book of the Bible? (Christian apologetics)

- The Gospel of Thomas and Jesus

- The Nag Hammadi Library

- An examination of the Gospel of Thomas by a Christian apologetics thinktank

Translations

- Patterson-Meyer Translation

- Patterson-Meyer Translation

- Thomas Lambdin Translation

- Various Translations

- Patterson and Robinson Translation

- Brill Literal Translation

- Coptic Interlineal Gospel of Thomas

- Gospel of Thomas - Many Translations and Resources

Translations with commentaries

- Hugh McGregor Ross' translation and commentary

- Gospel of Thomas with detailed comparisons with canonical sayings

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.