Difference between revisions of "Ghost Dance" - New World Encyclopedia

| (23 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

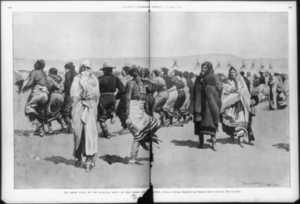

| + | [[Image:Ghost Dance at Pine Ridge.png|300px|thumb|right|The Ghost Dance by the Ogalala Lakota at Pine Ridge. Illustration by [[Frederic Remington]]]] | ||

| − | + | The '''Ghost Dance''' was a religious movement that began in 1889 and was readily incorporated into numerous [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native American]] belief systems. At the core of the movement was the visionary Indian leader [[Wovoka|Jack Wilson]], known as Wovoka among the [[Paiute]]. Wovoka prophesied an end to white American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and peace between whites and Indians. | |

| − | + | First performed in accordance with Wilson's teachings among the [[Nevada]] [[Paiute]], the Ghost Dance is built on the foundation of the traditional [[circle dance]]. The practice swept throughout much of the American West, quickly reaching areas of [[California]] and [[Oklahoma]]. As it spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs, creating changes in both the [[society]] that integrated it and the ritual itself. | |

| − | + | The Ghost Dance took on a more militant character among the Lakota [[Sioux]] who were suffering under the disastrous US government policy that had sub-divided their original reservation land and forced them to turn to agriculture. By performing the Ghost Dance, the Lakota believed they could take on a "Ghost Shirt" capable of repelling the white man's [[bullet]]s. Seeing the Ghost Dance as a threat and seeking to suppress it, U.S. Government Indian agents initiated actions that tragically culminated with the death of [[Sitting Bull]] and the later [[Wounded Knee massacre]]. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The Ghost Dance and its ideals as taught by Wokova soon began to lose energy and it faded from the scene, although some tribes still practiced into the twentieth century. | ||

==Historical foundations== | ==Historical foundations== | ||

| + | ===Round-dance precursors=== | ||

| + | The physical form of the ritual associated with the Ghost Dance religion did not originate with [[Jack Wilson]] ([[Wovoka]]), nor did it die with him. Referred to as the "round dance," this ritual form characteristically includes a circular community dance held around an individual who leads the ceremony. Often accompanying the ritual are intermissions of [[trance]], exhortations, and [[prophecy|prophesying]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The term “[[Prophetic dance|prophet dances]]” was applied during an investigation of Native American rituals carried out by [[anthropologist]] [[Leslie Spier]], a student of [[Franz Boas]], the German-born American pioneer of modern [[anthropology]]. Spier noted that versions of the round dance were present throughout much of the [[Pacific Northwest]] including the [[Columbia River Plateau|Columbia plateau]] (a region including [[Washington]], [[Oregon]], [[Idaho]], and parts of western [[Montana]]). | ||

| + | |||

===Paiute background=== | ===Paiute background=== | ||

| − | The [[Northern Paiute]]s living in [[Mason Valley]], | + | The [[Northern Paiute]]s living in [[Mason Valley]], Nevada thrived on a subsistence pattern of [[foraging]] for ''[[cyperus]]'' bulbs for part of the year and augmenting their diets with fish, [[pine nuts]], and occasionally wild game killed by clubbing it. Their social system had little hierarchy and relied instead on [[shaman]]s who as self-proclaimed spiritually-blessed individuals organized events for the group as a whole. Usually, community events centered on the observance of a ritual at prescribed times of year, such as harvests or hunting parties. |

| − | + | An extraordinary instance occurred in 1869 when the shaman [[Wodziwob]] organized a series of community dances to announce his [[vision]]. He spoke of a journey to the land of the dead and of promises made to him by the souls of the recently deceased. They promised to return to their loved ones within a period of three to four years. Wodziwob’s peers accepted this vision, probably due to his already-reputable status as a [[healer]], as he urged his people to dance the common circle dance as was customary during a time of festival. He continued preaching this message for three years with the help of a local "weather doctor" named [[Tavibo]], the father of Jack Wilson (Wovoka). | |

| − | |||

| − | Wodziwob’s peers accepted this vision, probably due to his already reputable status as a [[healer]], as he urged | ||

Prior to [[Wodziwob]]’s religious movement, a devastating [[typhoid]] epidemic struck in 1867. This, and other European diseases, killed approximately one-tenth of the total population, resulting in widespread psychological and emotional trauma, which brought grave disorder to the [[economic system]]. Many families were prevented from continuing their [[nomadic]] lifestyle, following pine nut harvests and wild game herds. Left with few options, many families ended up in [[Virginia City]] seeking wage work. | Prior to [[Wodziwob]]’s religious movement, a devastating [[typhoid]] epidemic struck in 1867. This, and other European diseases, killed approximately one-tenth of the total population, resulting in widespread psychological and emotional trauma, which brought grave disorder to the [[economic system]]. Many families were prevented from continuing their [[nomadic]] lifestyle, following pine nut harvests and wild game herds. Left with few options, many families ended up in [[Virginia City]] seeking wage work. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Wovoka's vision== |

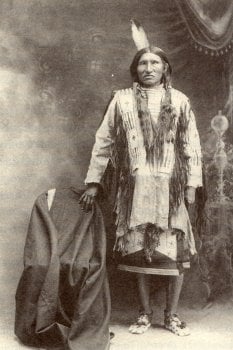

| − | + | [[Image:Wovoka_Paiute_Shaman.jpg|thumb|Wovoka – [[Paiute]] spiritual leader and creator of the Ghost Dance]] | |

| + | Jack Wilson, the [[Paiute]] [[prophet]] formerly known as [[Wovoka]] until his adoption of an Anglo name, was believed to have experienced a [[Hallucination|vision]] during a [[solar eclipse]] on January 1, 1889. It was reportedly not his first time experiencing a vision directly from God; but as a young adult, he claimed that he was then better equipped, spiritually, to handle this message. | ||

| − | + | Wilson had received training from an experienced [[shaman]] under his parents' guidance after they realized that he was having difficulty interpreting his previous visions. He was also in training to be a "weather doctor," following in his father’s footsteps, and was known in Mason Valley as a gifted young leader. He often presided over circle dances, while preaching a message of universal love. In addition, he had reportedly been influenced by the Christian teaching of Presbyterians for whom he had worked as a ranch hand, by local Mormons, and by the Indian Shaker Church. | |

| − | + | [[Anthropology|Anthropologist]] [[James Mooney]] conducted an interview with Wilson in 1892. Wilson told Mooney that he had stood before God in Heaven, and had seen many of his ancestors engaged in their favorite pastimes. God showed Wilson a beautiful land filled with wild game, and instructed him to return home to tell his people that they must love each other, not fight, and live in peace with the whites. God also stated that Wilson's people must work, not steal or lie, and that they must not engage in the old practices of war or the self-mutilation traditions connected with [[mourning]] the dead. God said that if his people kept by these rules, they would be united with their friends and family in the other world. | |

| − | + | In God's presence, Wilson proclaimed, there would be no sickness, disease, or old age. According to Wilson, he was then given the formula for the proper conduct of the Ghost Dance and commanded to bring it back to his people. Wilson preached that if this five-day dance was performed in the proper intervals, the performers would secure their happiness and hasten the reunion of the living and deceased. God purportedly gave Wilson powers over weather and told him that he would be the divine deputy in charge of affairs in the Western United States, leaving current [[Benjamin Harrison|President Harrison]] as God’s deputy in the East. Wilson claims that he was then told to return home and preach God’s message. | |

| − | + | Mooney's study also compared letters between tribes and notes that Wilson had asked his pilgrims to take upon their arrival at Mason Valley. These confirmed that the teaching Wilson explained directly to Mooney was essentially the same as was being spread to the neighboring tribes. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Wilson | + | Wilson claimed to have left the presence of God convinced that if every Indian in the West danced the new dance to “hasten the event,” all evil in the world would be swept away leaving a renewed Earth filled with food, love, and faith. Quickly accepted by his Paiute brethren, the new religion was termed “Dance In A Circle." Because the first Anglo contact with the practice came by way of the Sioux, their expression "Spirit Dance" was adopted as a descriptive title for all such practices. This was subsequently translated as "Ghost Dance." |

| − | + | ==Role in Wounded Knee Massacre== | |

| + | Wovoka’s message spread across much of the western portion of the United States, reportedly prevalent as far east as the Missouri River, north to the Canadian border, west to the Sierra Nevada, and south to northern Texas. Many tribes sent members to investigate the self-proclaimed prophet. Many left as believers and returned to their homelands preaching his message. The Ghost Dance was also investigated by a number of [[Mormons]] from [[Utah]], who generally found the teaching unobjectionable. Some practitioners of the dance saw Wokova as a new Messiah, and government Indian agents in some areas began to see the movement as a potential threat. | ||

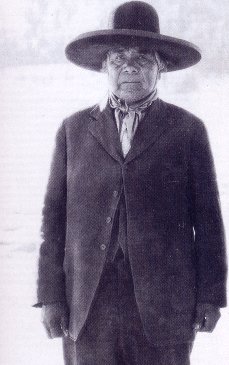

| − | + | [[Image:Kickingbear.jpg|thumb|Kicking Bear, who brought the "Ghost Shirt" concept to the Lakota Sioux]] | |

| − | + | While most followers of the Ghost Dance understood Wovoka's role as being that of a teacher of peace, others took a more warlike posture. An alternate interpretation of the Ghost Dance tradition may be seen in the so-called "Ghost Shirts," which were special [[garments]] rumored to repel bullets through spiritual power. Despite the uncertainty of its origins, it is generally accepted that chief [[Kicking Bear]] brought the concept to his people, the [[Lakota Sioux]] in 1890. | |

| − | + | Another Lakota interpretation of Wovoka's religion is drawn from the idea of a "renewed Earth," in which "all evil is washed away." This Lakota interpretation included the removal of all [[Anglo Americans]] from their lands, unlike Wovoka's version of the Ghost Dance, which encouraged co-existence with Anglos. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In February 1890, the United States government unilaterally divided the [[Great Sioux Reservation]] of [[South Dakota]] into five smaller reservations. This was done to accommodate white homesteaders from the Eastern [[United States]], even though it broke a treaty signed earlier between the U.S. and the Lakota Sioux. Once settled on the reduced reservations, tribes were separated into family units on 320-acre plots, forced to farm, raise livestock, and send their children to [[Carlisle Indian School|boarding schools]] that forbade any inclusion of Native American traditional culture and language. | |

| − | + | To help support the Sioux during the period of transition, the [[Bureau of Indian Affairs]] (BIA), was delegated the responsibility of supplementing the Sioux economy with food distributions and hiring white farmers as teachers for the people. The farming plan failed to take into account the difficulty Sioux farmers would have in trying to cultivate crops in the semi-arid region of South Dakota. By the end of the 1890 growing season, a time of intense heat and low rainfall, it was clear that the land was unable to produce substantial agricultural yields. Unfortunately, this was also the time when the government’s patience with supporting the Indians ran out, resulting in rations to the Sioux being cut in half. With the [[bison]] virtually eradicated from the plains a few years earlier, the Sioux had few options available to escape starvation. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Sitting Bull.jpg|thumb|125px|left|Sitting Bull]] | |

| + | Increasingly frequent performances of the Ghost-Dance ritual ensued, frightening the supervising agents of the BIA. Chief Kicking Bear was forced to leave [[Standing Rock]], but when the dances continued unabated, Agent McLaughlin asked for more troops, claiming that [[Hunkpapa]] spiritual leader [[Sitting Bull]] was the real leader of the movement. A former agent, [[Valentine McGillycuddy]], saw nothing extraordinary in the dances and he ridiculed the panic that seemed to have overcome the agencies, saying: "If the [[Seventh-Day Adventists]] prepare the ascension robes for the Second Coming of the Savior, the United States Army is not put in motion to prevent them. Why should not the Indians have the same privilege? If the troops remain, trouble is sure to come."<ref>[http://www.hanksville.org/daniel/lakota/Ghost_Dance.html Ghost Dance]. ''www.hanksville.org''. Retrieved September 22, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Nonetheless, thousands of additional [[U.S. Army]] troops were deployed to the reservation. On December 15, 1890, [[Sitting Bull]] was arrested for failing to stop his people from practicing the Ghost Dance. During the incident, a Sioux Indian witnessing the arrest fired his gun at one of the soldiers, prompting an immediate retaliation; this conflict resulted in deaths on both sides, including Sitting Bull himself. | |

| − | + | [[Image:DeadBigfoot.jpg|250px|thumb|Wounded Knee Massacre|right|[[Miniconjou]] Chief [[Big Foot]] lies dead in the snow]] | |

| − | + | [[Big Foot]], a Miniconjou leader on the U.S. Army’s list of trouble-making Indians, was stopped while en route to convene with the remaining Sioux chiefs. U.S. Army officers forced him and his people to relocate to a small camp close to the [[Pine Ridge Indian Reservation|Pine Ridge]] Agency so that the soldiers could more closely watch the old chief. That evening, December 28, the small band of Sioux erected their tipis on the banks of [[Wounded Knee Creek]]. The following day, during an attempt by the officers to collect any remaining weapons from the band, one young and reportedly deaf Sioux warrior refused to relinquish his arms. A struggle followed in which a weapon discharged into the air. One United States' officer gave the command to open fire and the Sioux reacted by taking up previously confiscated weapons; the U.S. forces responded with [[carbine]] firearms and several rapid-fire light-artillery guns mounted on the overlooking hill. When the fighting had concluded, 25 United States soldiers lay dead—many reportedly killed by friendly fire—among the 153 dead Sioux, most were women and children. | |

| − | + | Following the massacre, chief [[Kicking Bear]] officially surrendered his weapon to Gen. [[Nelson A. Miles]]. Outrage in the Eastern states emerged as the general population learned about the events that had transpired. The United States Government had insisted on numerous occasions that the Native Indian populations had already been successfully pacified, and many Americans felt that Army actions were harsh; some related the massacre at Wounded Knee Creek to the "ungentlemanly act of kicking a man when he is already down." Public uproar played a role in the reinstatement of the previous treaty’s terms including full rations and additional monetary compensation for lands taken. | |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | After the tragic incident at Wounded Knee, the Ghost Dance gradually faded from the scene. The dance was still practiced in the twentieth century by some tribes, and has recently been revived occasionally. Anthropologists have studied the Ghost Dance extensively, seeing in it a transition from traditional Native American [[shaman]]ism to a more Christianized tradition capable of accommodating the culture of the white man. | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | |||

| − | + | *Brown, Dee. ''Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West.'' Owl Books, Henry Holt, 2001. ISBN 978-0805066692 | |

| − | *Brown, Dee. ''Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West'' | + | *Du Bois, Cora. ''The 1870 Ghost Dance.'' Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0803266629 |

| − | *Du Bois, Cora. ''The 1870 Ghost Dance'', University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0803266629 | + | *Kehoe, B Alice. ''The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization.'' Longrove, IL: Waveland Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1577664536 |

| − | *Kehoe, B Alice. ''The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization'', Waveland Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1577664536 | + | *La Barre, Weston. ''The Ghost Dance: Origins of Religion.'' Devon, UK: and Australia: Allen and Unwin, 1972. ISBN 978-0042110035 |

| − | *La Barre, Weston. ''The Ghost Dance: Origins of Religion'', Allen and Unwin, 1972. ISBN 978-0042110035 | + | *Mooney, James. ''The Ghost-Dance Religion and Wounded Knee.'' Dover Publications, 2011 (original 1991). ISBN 978-0486267593 |

| − | *Mooney, James. ''The Ghost-Dance Religion and Wounded Knee'' | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved June 21, 2017. | |

| − | *[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cI0Jfdkq4z8 | + | * Ahwahneechee Channel [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cI0Jfdkq4z8 "Wovoka and the Ghost Dance" video]. ''www.youtube.com''. |

| − | |||

{{Credit|145736620}} | {{Credit|145736620}} | ||

| + | [[Category:History]] | ||

Latest revision as of 18:46, 8 December 2022

The Ghost Dance was a religious movement that began in 1889 and was readily incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. At the core of the movement was the visionary Indian leader Jack Wilson, known as Wovoka among the Paiute. Wovoka prophesied an end to white American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and peace between whites and Indians.

First performed in accordance with Wilson's teachings among the Nevada Paiute, the Ghost Dance is built on the foundation of the traditional circle dance. The practice swept throughout much of the American West, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As it spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs, creating changes in both the society that integrated it and the ritual itself.

The Ghost Dance took on a more militant character among the Lakota Sioux who were suffering under the disastrous US government policy that had sub-divided their original reservation land and forced them to turn to agriculture. By performing the Ghost Dance, the Lakota believed they could take on a "Ghost Shirt" capable of repelling the white man's bullets. Seeing the Ghost Dance as a threat and seeking to suppress it, U.S. Government Indian agents initiated actions that tragically culminated with the death of Sitting Bull and the later Wounded Knee massacre.

The Ghost Dance and its ideals as taught by Wokova soon began to lose energy and it faded from the scene, although some tribes still practiced into the twentieth century.

Historical foundations

Round-dance precursors

The physical form of the ritual associated with the Ghost Dance religion did not originate with Jack Wilson (Wovoka), nor did it die with him. Referred to as the "round dance," this ritual form characteristically includes a circular community dance held around an individual who leads the ceremony. Often accompanying the ritual are intermissions of trance, exhortations, and prophesying.

The term “prophet dances” was applied during an investigation of Native American rituals carried out by anthropologist Leslie Spier, a student of Franz Boas, the German-born American pioneer of modern anthropology. Spier noted that versions of the round dance were present throughout much of the Pacific Northwest including the Columbia plateau (a region including Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of western Montana).

Paiute background

The Northern Paiutes living in Mason Valley, Nevada thrived on a subsistence pattern of foraging for cyperus bulbs for part of the year and augmenting their diets with fish, pine nuts, and occasionally wild game killed by clubbing it. Their social system had little hierarchy and relied instead on shamans who as self-proclaimed spiritually-blessed individuals organized events for the group as a whole. Usually, community events centered on the observance of a ritual at prescribed times of year, such as harvests or hunting parties.

An extraordinary instance occurred in 1869 when the shaman Wodziwob organized a series of community dances to announce his vision. He spoke of a journey to the land of the dead and of promises made to him by the souls of the recently deceased. They promised to return to their loved ones within a period of three to four years. Wodziwob’s peers accepted this vision, probably due to his already-reputable status as a healer, as he urged his people to dance the common circle dance as was customary during a time of festival. He continued preaching this message for three years with the help of a local "weather doctor" named Tavibo, the father of Jack Wilson (Wovoka).

Prior to Wodziwob’s religious movement, a devastating typhoid epidemic struck in 1867. This, and other European diseases, killed approximately one-tenth of the total population, resulting in widespread psychological and emotional trauma, which brought grave disorder to the economic system. Many families were prevented from continuing their nomadic lifestyle, following pine nut harvests and wild game herds. Left with few options, many families ended up in Virginia City seeking wage work.

Wovoka's vision

Jack Wilson, the Paiute prophet formerly known as Wovoka until his adoption of an Anglo name, was believed to have experienced a vision during a solar eclipse on January 1, 1889. It was reportedly not his first time experiencing a vision directly from God; but as a young adult, he claimed that he was then better equipped, spiritually, to handle this message.

Wilson had received training from an experienced shaman under his parents' guidance after they realized that he was having difficulty interpreting his previous visions. He was also in training to be a "weather doctor," following in his father’s footsteps, and was known in Mason Valley as a gifted young leader. He often presided over circle dances, while preaching a message of universal love. In addition, he had reportedly been influenced by the Christian teaching of Presbyterians for whom he had worked as a ranch hand, by local Mormons, and by the Indian Shaker Church.

Anthropologist James Mooney conducted an interview with Wilson in 1892. Wilson told Mooney that he had stood before God in Heaven, and had seen many of his ancestors engaged in their favorite pastimes. God showed Wilson a beautiful land filled with wild game, and instructed him to return home to tell his people that they must love each other, not fight, and live in peace with the whites. God also stated that Wilson's people must work, not steal or lie, and that they must not engage in the old practices of war or the self-mutilation traditions connected with mourning the dead. God said that if his people kept by these rules, they would be united with their friends and family in the other world.

In God's presence, Wilson proclaimed, there would be no sickness, disease, or old age. According to Wilson, he was then given the formula for the proper conduct of the Ghost Dance and commanded to bring it back to his people. Wilson preached that if this five-day dance was performed in the proper intervals, the performers would secure their happiness and hasten the reunion of the living and deceased. God purportedly gave Wilson powers over weather and told him that he would be the divine deputy in charge of affairs in the Western United States, leaving current President Harrison as God’s deputy in the East. Wilson claims that he was then told to return home and preach God’s message.

Mooney's study also compared letters between tribes and notes that Wilson had asked his pilgrims to take upon their arrival at Mason Valley. These confirmed that the teaching Wilson explained directly to Mooney was essentially the same as was being spread to the neighboring tribes.

Wilson claimed to have left the presence of God convinced that if every Indian in the West danced the new dance to “hasten the event,” all evil in the world would be swept away leaving a renewed Earth filled with food, love, and faith. Quickly accepted by his Paiute brethren, the new religion was termed “Dance In A Circle." Because the first Anglo contact with the practice came by way of the Sioux, their expression "Spirit Dance" was adopted as a descriptive title for all such practices. This was subsequently translated as "Ghost Dance."

Role in Wounded Knee Massacre

Wovoka’s message spread across much of the western portion of the United States, reportedly prevalent as far east as the Missouri River, north to the Canadian border, west to the Sierra Nevada, and south to northern Texas. Many tribes sent members to investigate the self-proclaimed prophet. Many left as believers and returned to their homelands preaching his message. The Ghost Dance was also investigated by a number of Mormons from Utah, who generally found the teaching unobjectionable. Some practitioners of the dance saw Wokova as a new Messiah, and government Indian agents in some areas began to see the movement as a potential threat.

While most followers of the Ghost Dance understood Wovoka's role as being that of a teacher of peace, others took a more warlike posture. An alternate interpretation of the Ghost Dance tradition may be seen in the so-called "Ghost Shirts," which were special garments rumored to repel bullets through spiritual power. Despite the uncertainty of its origins, it is generally accepted that chief Kicking Bear brought the concept to his people, the Lakota Sioux in 1890.

Another Lakota interpretation of Wovoka's religion is drawn from the idea of a "renewed Earth," in which "all evil is washed away." This Lakota interpretation included the removal of all Anglo Americans from their lands, unlike Wovoka's version of the Ghost Dance, which encouraged co-existence with Anglos.

In February 1890, the United States government unilaterally divided the Great Sioux Reservation of South Dakota into five smaller reservations. This was done to accommodate white homesteaders from the Eastern United States, even though it broke a treaty signed earlier between the U.S. and the Lakota Sioux. Once settled on the reduced reservations, tribes were separated into family units on 320-acre plots, forced to farm, raise livestock, and send their children to boarding schools that forbade any inclusion of Native American traditional culture and language.

To help support the Sioux during the period of transition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), was delegated the responsibility of supplementing the Sioux economy with food distributions and hiring white farmers as teachers for the people. The farming plan failed to take into account the difficulty Sioux farmers would have in trying to cultivate crops in the semi-arid region of South Dakota. By the end of the 1890 growing season, a time of intense heat and low rainfall, it was clear that the land was unable to produce substantial agricultural yields. Unfortunately, this was also the time when the government’s patience with supporting the Indians ran out, resulting in rations to the Sioux being cut in half. With the bison virtually eradicated from the plains a few years earlier, the Sioux had few options available to escape starvation.

Increasingly frequent performances of the Ghost-Dance ritual ensued, frightening the supervising agents of the BIA. Chief Kicking Bear was forced to leave Standing Rock, but when the dances continued unabated, Agent McLaughlin asked for more troops, claiming that Hunkpapa spiritual leader Sitting Bull was the real leader of the movement. A former agent, Valentine McGillycuddy, saw nothing extraordinary in the dances and he ridiculed the panic that seemed to have overcome the agencies, saying: "If the Seventh-Day Adventists prepare the ascension robes for the Second Coming of the Savior, the United States Army is not put in motion to prevent them. Why should not the Indians have the same privilege? If the troops remain, trouble is sure to come."[1]

Nonetheless, thousands of additional U.S. Army troops were deployed to the reservation. On December 15, 1890, Sitting Bull was arrested for failing to stop his people from practicing the Ghost Dance. During the incident, a Sioux Indian witnessing the arrest fired his gun at one of the soldiers, prompting an immediate retaliation; this conflict resulted in deaths on both sides, including Sitting Bull himself.

Big Foot, a Miniconjou leader on the U.S. Army’s list of trouble-making Indians, was stopped while en route to convene with the remaining Sioux chiefs. U.S. Army officers forced him and his people to relocate to a small camp close to the Pine Ridge Agency so that the soldiers could more closely watch the old chief. That evening, December 28, the small band of Sioux erected their tipis on the banks of Wounded Knee Creek. The following day, during an attempt by the officers to collect any remaining weapons from the band, one young and reportedly deaf Sioux warrior refused to relinquish his arms. A struggle followed in which a weapon discharged into the air. One United States' officer gave the command to open fire and the Sioux reacted by taking up previously confiscated weapons; the U.S. forces responded with carbine firearms and several rapid-fire light-artillery guns mounted on the overlooking hill. When the fighting had concluded, 25 United States soldiers lay dead—many reportedly killed by friendly fire—among the 153 dead Sioux, most were women and children.

Following the massacre, chief Kicking Bear officially surrendered his weapon to Gen. Nelson A. Miles. Outrage in the Eastern states emerged as the general population learned about the events that had transpired. The United States Government had insisted on numerous occasions that the Native Indian populations had already been successfully pacified, and many Americans felt that Army actions were harsh; some related the massacre at Wounded Knee Creek to the "ungentlemanly act of kicking a man when he is already down." Public uproar played a role in the reinstatement of the previous treaty’s terms including full rations and additional monetary compensation for lands taken.

Legacy

After the tragic incident at Wounded Knee, the Ghost Dance gradually faded from the scene. The dance was still practiced in the twentieth century by some tribes, and has recently been revived occasionally. Anthropologists have studied the Ghost Dance extensively, seeing in it a transition from traditional Native American shamanism to a more Christianized tradition capable of accommodating the culture of the white man.

Notes

- ↑ Ghost Dance. www.hanksville.org. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Owl Books, Henry Holt, 2001. ISBN 978-0805066692

- Du Bois, Cora. The 1870 Ghost Dance. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0803266629

- Kehoe, B Alice. The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization. Longrove, IL: Waveland Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1577664536

- La Barre, Weston. The Ghost Dance: Origins of Religion. Devon, UK: and Australia: Allen and Unwin, 1972. ISBN 978-0042110035

- Mooney, James. The Ghost-Dance Religion and Wounded Knee. Dover Publications, 2011 (original 1991). ISBN 978-0486267593

External links

All links retrieved June 21, 2017.

- Ahwahneechee Channel "Wovoka and the Ghost Dance" video. www.youtube.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.