Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "G. Stanley Hall" - New World

(→Legacy) |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

{{epname}} | {{epname}} | ||

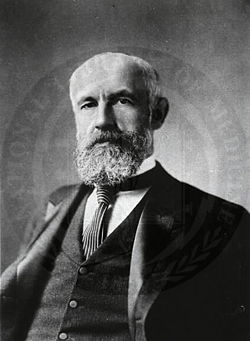

| − | '''Granville Stanley Hall''' (February 1, 1844 - April 24, 1924) was an American psychologist and educator who pioneered [[United States|American]] [[psychology]]. His interests focused on childhood development and evolutionary theory. Hall was the first president of the [[American Psychological Association]] and the first president of [[Clark University]].[[Image:G_Stanley_Hall.jpg|thumb|250px|Granville Stanley Hall, circa 1910.]] | + | '''Granville Stanley Hall''' (February 1, 1844 - April 24, 1924) was an American psychologist and educator who pioneered [[United States|American]] [[psychology]]. His interests focused on childhood development and evolutionary theory. Hall was the first president of the [[American Psychological Association]] and the first president of [[Clark University]]. Hall's impact upon psychology was both direct in his work as scholar, leader, and educator, and indirect through his influence as a respected writer and speaker to educational societies and to lay audiences.[[Image:G_Stanley_Hall.jpg|thumb|250px|Granville Stanley Hall, circa 1910.]] |

=Life= | =Life= | ||

Granville Stanley Hall was born in [[Ashfield, Massachusetts|Ashfield]], [[Massachusetts]]. He graduated from [[Williams College]] in [[1867]], then studied at the [[Union Theological Seminary]] to prepare as a clergyman, but found little success as a Methodist minister. Soon, he left for Germany for three years, where he studied philosophy and also attended ''Du Bois-Reymond'' lectures on [[physiology]]. Returning to New York in 1871, he completed his divinity degree and served briefly at a country church. He then secured a position at Antioch College near Dayton, Ohio, and taught a variety of courses. | Granville Stanley Hall was born in [[Ashfield, Massachusetts|Ashfield]], [[Massachusetts]]. He graduated from [[Williams College]] in [[1867]], then studied at the [[Union Theological Seminary]] to prepare as a clergyman, but found little success as a Methodist minister. Soon, he left for Germany for three years, where he studied philosophy and also attended ''Du Bois-Reymond'' lectures on [[physiology]]. Returning to New York in 1871, he completed his divinity degree and served briefly at a country church. He then secured a position at Antioch College near Dayton, Ohio, and taught a variety of courses. | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

In 1904, Hall published an original work in psychology focusing on [[adolescence]] — '''Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relation to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education''', which was read and discussed by psychologists, educators, medical doctors, other professionals, and also by parents. Its focus on adolescence fed a growing nationqal concern in the early twentieth century about issues of femininity, masculinity, coeducation, and concern over appropriate information and experience for adolescents growing into adulthood. | In 1904, Hall published an original work in psychology focusing on [[adolescence]] — '''Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relation to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education''', which was read and discussed by psychologists, educators, medical doctors, other professionals, and also by parents. Its focus on adolescence fed a growing nationqal concern in the early twentieth century about issues of femininity, masculinity, coeducation, and concern over appropriate information and experience for adolescents growing into adulthood. | ||

| − | + | In 1922, Hall published his final work, ''Senescence'', a study of old age. By this time Hall himself was no longer at Clark University, having retired as president in 1920, and was struggling with personal definitions of retirement and the process of [[aging]] as final points of development. In the book, Hall called for a new definition of aging, not as degeneration, which might be predicted from his recapitulation theory, but rather as a stage of psychological renewal and creativity. Hall's view of aging was not significantly different from those views advocated by other scholars and, as with others, Hall fell victim to an understanding of aging that held the individual responsible for psychological health in old age, relegating culture and its construction of aging to a minor role. | |

==Criticism== | ==Criticism== | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

Hall founded a number of journals to provide a forum for research and schlarship in psychology: ''American Journal of Psychology'', founded in 1887, and still is being published today.; ''Pedagogical Seminary'' (now under the title of ''Journal of Genetic Psychology''); ''Journal of Applied Psychology''; ''Journal of Religious Psychology''. Hall did make psychology functional and left it firmly intrenched in America. | Hall founded a number of journals to provide a forum for research and schlarship in psychology: ''American Journal of Psychology'', founded in 1887, and still is being published today.; ''Pedagogical Seminary'' (now under the title of ''Journal of Genetic Psychology''); ''Journal of Applied Psychology''; ''Journal of Religious Psychology''. Hall did make psychology functional and left it firmly intrenched in America. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At [[John Hopkins]], Hall's course in ''Laboratory Psychology'' attracted students such as [[John Dewey]], [[James McKeen Cattell]], [[Joseph Jastrow]]. Other students influenced and taught by Hall included ''Arnold Gesell'', ''Henry Goddard'', [[Edmund C. Sanford]], and ''Lewis M. Terman''. Although all of these students moved beyond the influence of Hall, his interest and insistence upon psychology as an experimental endeavor served as a catalyst for much of their later work. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 49: | Line 51: | ||

*Diehl, L. A. 1987. The Paradox of G. Stanley Hall: Foe of coeducation and educator of women. ''American Psychologist'', 41(8), 868-878. | *Diehl, L. A. 1987. The Paradox of G. Stanley Hall: Foe of coeducation and educator of women. ''American Psychologist'', 41(8), 868-878. | ||

*Galton, F. 1889. '''Natural inheritance'''. London: Macmillan. | *Galton, F. 1889. '''Natural inheritance'''. London: Macmillan. | ||

| − | *Hall, G. S.1917. '''The life and confessions of a psychologist'''. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. | + | *Hall, G. S. '''Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relation to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education''' (Vols 1 & 2). New York: Appleton. |

| + | *Hall, G. S. 1917. '''The life and confessions of a psychologist'''. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. | ||

| + | *Hall, G. S. 1922. '''Senescence'''. New York: Appleton. | ||

*Koch, S. 1941. The logical character of the motivation concept. ''Psychological Review'', 48, 15-38 and 127-154. | *Koch, S. 1941. The logical character of the motivation concept. ''Psychological Review'', 48, 15-38 and 127-154. | ||

*Leahey, Th. H. 1991. '''A History of Modern Psychology'''. Englewood Cliff, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. | *Leahey, Th. H. 1991. '''A History of Modern Psychology'''. Englewood Cliff, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. | ||

| Line 60: | Line 64: | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

* {{gutenberg author| id=G.+Stanley+Hall | name=G. Stanley Hall}} | * {{gutenberg author| id=G.+Stanley+Hall | name=G. Stanley Hall}} | ||

| + | *Hall, G. S. (1988-1920) G. Stanley Hall papers. Available from Clark University Archives, Goddard Library, Clark University, Wocester, MA. | ||

* [http://vlp.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/people/data?id=per297 Biography and bibliography] in the Virtual Laboratory of the [[Max Planck Institute for the History of Science]] | * [http://vlp.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/people/data?id=per297 Biography and bibliography] in the Virtual Laboratory of the [[Max Planck Institute for the History of Science]] | ||

{{Credit1|G._Stanley_Hall|87538986|}} | {{Credit1|G._Stanley_Hall|87538986|}} | ||

Revision as of 02:30, 18 January 2007

Granville Stanley Hall (February 1, 1844 - April 24, 1924) was an American psychologist and educator who pioneered American psychology. His interests focused on childhood development and evolutionary theory. Hall was the first president of the American Psychological Association and the first president of Clark University. Hall's impact upon psychology was both direct in his work as scholar, leader, and educator, and indirect through his influence as a respected writer and speaker to educational societies and to lay audiences.

Life

Granville Stanley Hall was born in Ashfield, Massachusetts. He graduated from Williams College in 1867, then studied at the Union Theological Seminary to prepare as a clergyman, but found little success as a Methodist minister. Soon, he left for Germany for three years, where he studied philosophy and also attended Du Bois-Reymond lectures on physiology. Returning to New York in 1871, he completed his divinity degree and served briefly at a country church. He then secured a position at Antioch College near Dayton, Ohio, and taught a variety of courses.

Inspired by Wilhelm Wundt's Principles of Physiological Psychology, Hall set out again for Germany to learn from Wundt. However, president Eliot of Harvard University offered him a teaching post in English, which also allowed him to work with William James. He received his doctorate in 1878 for a dissertation on muscular perception. From then to 1880 Hall spent in Germany, where he worked for Wundt during the first year of the Leipzig laboratory.

Career and Work

In 1881, Hall joined the new graduate[[ John Hopkins University], where he worked with young people who later went on to positions of note within psychology, among them John Dewey, James McKeen Cattell, and Edward Clark Sanford.

Hall continued his career by teaching English and philosophy at Antioch College in Ohio. In 1882 (until 1888), he was appointed as a Professor of Psychology and Pedagogics at Johns Hopkins University, and began what is considered to be the first American psychology laboratory [1]. There, Hall objected vehemently to the emphasis on teaching traditional subjects, e.g., Latin, mathematics, science and history, in high school, arguing instead that high school should focus more on the education of adolescents than on preparing students for college.

In 1889, Hall was named to the first Presidency of Clark University, a post he filled until 1920. During his 31 years as President at Clark University, Hall remained intellectually active. He was instrumental in the development of educational psychology, and attempted to determine the effect adolescence has on education. He was also responsible for inviting Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung to visit and deliver lectures in 1909. In 1887, he founded the American Journal of Psychology and in 1892 was appointed as the first president of the American Psychological Association.

In the year of his death, Hall was elected to a second term as president of the American Psychological Association; the only other person to be so honored was William James.

Contributions

G. Stanley Hall, like [[William [James]] did not have the temperament for laboratory work. Rather he created an intellectual atmosphere to support those who were more empirically inclined. Nevertheless, Hall did contribute to the emerging body of psychological knowledge. Specifically, he was convinced of the importance of genetics and evolution for psychology, which was reflected in his writings and his support of the study of developmental psychology in terms of phylogenetic and ontogenetic perspectives. Darwin's Theory of Evolution and Ernst Haeckel's Theory of recapitulation were large influences on Hall's career. These ideas prompted Hall to examine aspects of childhood development in order to learn about the inheritance of behavior. The subjective character of these studies made their validation impossible. His work also delved into controversial portrayals of the differences between women and men, as well as the concept of racial eugenics[1].

Hall coined the phrase "Storm and Stress" with reference to adolescence, taken from the German Sturm und Drang-movement. Its three key aspects are: conflict with parents, mood disruptions, and risky behavior. As was later the case with the work of Lev Vygotsky and Jean Piaget, public interest in this phrase and Hall's originating role, faded. Recent research has led to some reconsideration of the phrase and its denotation. In its three aspects, recent evidence supports storm-and-stress, but modified to take into account individual differences and cultural variations. Currently, pyschologists do not accept storm-and-stress as universal, but do acknowledge the possibility in brief passing. Not all adolescents experience storm-and-stress, but storm-and-stress is more likely during adolescence than at other ages.

In 1904, Hall published an original work in psychology focusing on adolescence — Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relation to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education, which was read and discussed by psychologists, educators, medical doctors, other professionals, and also by parents. Its focus on adolescence fed a growing nationqal concern in the early twentieth century about issues of femininity, masculinity, coeducation, and concern over appropriate information and experience for adolescents growing into adulthood.

In 1922, Hall published his final work, Senescence, a study of old age. By this time Hall himself was no longer at Clark University, having retired as president in 1920, and was struggling with personal definitions of retirement and the process of aging as final points of development. In the book, Hall called for a new definition of aging, not as degeneration, which might be predicted from his recapitulation theory, but rather as a stage of psychological renewal and creativity. Hall's view of aging was not significantly different from those views advocated by other scholars and, as with others, Hall fell victim to an understanding of aging that held the individual responsible for psychological health in old age, relegating culture and its construction of aging to a minor role.

Criticism

In 1909, Hall began The Children's Institute at Clark University. The institute was founded with the double purpose of collecting data on children, which Hall initially hoped would create a psychology founded on genetic and evolutionary priciples (the direct outcome of his functionalist interest in mental adaptation) and of using those data to form the basis for sound educational practices. The institute functioned as as both a laboratory for data to confirm Hall's recapitulation theory, and as a program for teaching and promoting child study to teachers and others in education. The data were disapponting with respect to their ability to confirm Hall's theoretical bias. Therefore, the institute functioned primarily as an educational entity and drew interest of educators, teachers, and parents.

Hall did not start systems of psychology nor develop coherent theoretical frameworks nor leave behind loyal followers, but he was a loyal teacher and devoted organizer of psychology.

Legacy

Hall was instrumental in firmly establishing psychology in the United States through both substantive and practical activities. In addition to his contribution to child psychology and educational issues, he succeeded in securing recognition of psychology as profession. He was the most independent of the early American psychologists Hall's major books were Adolescence (1904) and Aspects of Child Life and Education (1921). Hall also coined the technical words describing types of tickling; knismesis or feather-like tickling, and gargalesis for the harder, laughter inducing type.

Hall founded a number of journals to provide a forum for research and schlarship in psychology: American Journal of Psychology, founded in 1887, and still is being published today.; Pedagogical Seminary (now under the title of Journal of Genetic Psychology); Journal of Applied Psychology; Journal of Religious Psychology. Hall did make psychology functional and left it firmly intrenched in America.

At John Hopkins, Hall's course in Laboratory Psychology attracted students such as John Dewey, James McKeen Cattell, Joseph Jastrow. Other students influenced and taught by Hall included Arnold Gesell, Henry Goddard, Edmund C. Sanford, and Lewis M. Terman. Although all of these students moved beyond the influence of Hall, his interest and insistence upon psychology as an experimental endeavor served as a catalyst for much of their later work.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ben-David, J.and Collins, R. 1966. Social factors in the origin of a new science: The case of psychology. American Psychological Review, 31, 451-465.

- Boring, E.G. 1950. A history of experimental psychology, 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Brennan, J.F. 1982. History and systems of psychology. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Dewey, J. 1886. Psychology. New York: Harper

- Diehl, L. A. 1987. The Paradox of G. Stanley Hall: Foe of coeducation and educator of women. American Psychologist, 41(8), 868-878.

- Galton, F. 1889. Natural inheritance. London: Macmillan.

- Hall, G. S. Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relation to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education (Vols 1 & 2). New York: Appleton.

- Hall, G. S. 1917. The life and confessions of a psychologist. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

- Hall, G. S. 1922. Senescence. New York: Appleton.

- Koch, S. 1941. The logical character of the motivation concept. Psychological Review, 48, 15-38 and 127-154.

- Leahey, Th. H. 1991. A History of Modern Psychology. Englewood Cliff, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Pruette, L. 1926. G. Stanley Hall: Biography of a mind. New York: Appleton.

- Ross, D. 1972. G. Stanley Hall: The psychologist as a prophet. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Stevens S. S. 1935. The operational definition of psychological concepts. Psychological Review, 42, 517-527.

- Williams, K. 1931. Five behaviorisms. American Journal of Psychology. 22, 337-361.

- Woodworth, R. S. 1924. Four varieties of behaviorism. Psychological Review, 31, 257-264.

External links

- Works by G. Stanley Hall. Project Gutenberg

- Hall, G. S. (1988-1920) G. Stanley Hall papers. Available from Clark University Archives, Goddard Library, Clark University, Wocester, MA.

- Biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.