Difference between revisions of "Donatist" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Background) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}} |

| − | The '''Donatist''' movement was a branch of Christianity in north Africa which began in | + | |

| + | [[Image:John William Waterhouse - Saint Eulalia - 1885.jpg|thumb|300px|[[Eulalia of Mérida]] was a Christian saint who intentionally challenged Roman authorities during the persecution of [[Diocletian]]'s era, an act forbidden by the bishops whom the Donatists opposed.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The '''Donatist''' movement was a branch of [[Christianity]] in north Africa, eventually deemed heretical, which began in the early fourth century C.E. and flourished for more than a century, surviving numerous persecutions by the new Christian [[Roman Empire]] until it finally disappeared in the wake of the [[Muslim]] conquest. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The movement that would later be called Donatism originated in the African capital of [[Carthage]], during the last great persecution of the Christian church by Emperor [[Diocletian]] in 303-305 C.E. The early Donatists were characterized by a determination to face [[martyr]]dom rather than cooperate with the Roman authorities who sought to force Christians to surrender their holy [[scripture]]s and other sacred objects. They refused to recognize as bishop a leader whose mentor had cooperated with Rome and had ordered Christians not to seek martyrdom. The [[schism]] is dated as beginning in 311, when the Donatists appointed a rival bishop instead. The movement takes it name from this bishop's successor, Donatus, who remained a bishop at Carthage, although occasionally forced into [[exile]], until his death in 355. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After [[Constantine the Great]] legalized and supported the Christian faith, the Donatists declared that priests and bishops who had cooperated with Rome during the persecutions could not administer valid [[sacrament]]s to their congregations. The movement spread throughout the [[Roman Empire]] and precipitated a widespread crisis as many "lapsed" priests returned to the fold to take advantage of the church's new found favor. The emperors generally supported the Catholic view that sacraments performed by sinful priests were still valid. Violent state repression of the Donatists failed to force them into submission in northern Africa, where they were often in the majority. Donatism survived into the sixth century and beyond, fading away only in the wake of the [[Muslim conquest]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The Donatist [[schism]] helped define the orthodox Church as "Catholic" (or Universal) and at the same time cemented an alliance between the church and the state which justified the use of state force against "[[heresy]]," a doctrine which lasted until the modern era. Some Protestant movements look to the Donatists as an example of opposition against the corruption of Catholicism and a pioneer in the struggle to achieve the [[separation of church and state]]. | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| − | |||

| − | Some of the | + | The Donatist movement's roots can be found in the persecution of the Christian church under [[Emperor Diocletian]]. On February 24, 303, the Emperor banned the Christian religion and commanded both the destruction of the churches and the burning of Christian scriptures. In 304, he issued an edict declaring that Christians must be willing to offer incense at the [[altar]]s of the state or face [[capital punishment]]. Many Christians met their death as a result. Some—eager for martyrdom—willingly informed authorities that they were Christians or even that they possessed sacred scriptures but refused to give them up. |

| + | |||

| + | The persecution lasted only a brief time in Africa but it was particularly severe there. [[Mensurius]], the Bishop of [[Carthage]], forbade intentional martyrdom and admitted to handing over what he called "heretical" scriptures to the authorities while supposedly hiding legitimate scriptures in his home. His arch[[deacon]], Cæcilianus, reportedly physically prevented the Carthaginian Christians from gathering for worship. On the other hand, [[Secundus]], the leading bishop of [[Numidia]], praised the [[martyr]]s who had been put to death for refusing to deliver up the scriptures. He declared himself "not a ''traditor''"—a term referring to those who had cooperated with authorities by giving them either holy scriptures, sacred church vessels, or the names and persons of fellow Christians. Some of the [[Christian]]s of Carthage and other cities broke off relations with Mensurius, considering him, rightly or wrongly, a ''traditor''. | ||

| + | |||

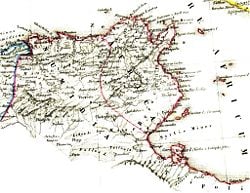

| + | By 305 the persecution had abated, and a church council, or ''[[synod]]'', was held at the Numidian city of [[Cirta]]. Bishop Secundus launched an investigation to ensure that there were no ''traditors'' present. [[Image:Numidia.jpg|thumb|250px|The provinces of Africa and Numidia, which Carthage shown at the northwest comer]] Shockingly, it was determined that most of the bishops fell under one definition or another of the term. When Mensurius died in 311, his protegé, Cæcilianus, succeeded him at Carthage. Secundus now convened another synod, and when Cæcilianus failed to appear to defend himself, he was deposed and excommunicated. The synod elected Majorinus in his place as Bishop of Carthage. When Majorinus himself soon died in 313, his successor would be [[Donatus]]. It is from this Donatus—characterized as a eloquent, learned leader of unbending faith—that the [[schism]] received its name. | ||

| − | + | Carthage now had two bishops and two competing congregations. The schism soon spread throughout the whole province, with a majority of the people, as well as a sizable number of bishops, supporting Donatus. Outside of [[Africa]], however, the bishops generally recognized Cæcilianus. | |

== The Donatist churches == | == The Donatist churches == | ||

| + | ===Theological issues=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Byzantinischer Mosaizist um 1000 002.jpg|thumb|Constantine the Great liberated the orthodox Christian Church, but ruled against the Donatists.]] | ||

| + | The Donatists' primary disagreement with the mainstream church was over the question of the legitimacy of [[sacrament]]s dispensed by ''traditors'' and other ''lapsed'' priests. Under the [[Emperor Constantine]], the issue became particularly intense, as many fallen-away priests returned to the church to take advantage of the favored positions they would now have under Constantine's protection and support. The Donatists, however, proclaimed that any sacraments celebrated by these ''lapsed'' priests and bishops were invalid. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Two theological questions now confronted the Church as a result of the [[schism]]. The first was whether the sacrament of ''[[penance]]'' can bring an apostate Christian, specifically the ''traditor'', into full communion. The Catholic answer was "yes." The Donatists, on the other hand, held that such a serious crime rendered one unfit for further membership in the Church. Indeed, the term ''Catholic'' (universal) came into frequent use during this time to express the universality of the orthodox position versus the more narrow insistence on holiness expressed by the Donatists. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Tertullian.JPG|thumb|125px|left|Tertullian, the Carthaginian Church Father whose views in some ways supported the Donatist position.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The second question was the validity of sacraments conferred by priests and bishops who had fallen away. The Donatists held that such sacraments were not valid. By their sinful act, ''lapsed'' clerics had rendered themselves incapable of celebrating Christ's holy sacraments. The Catholic position was that the validity of the sacrament depends upon the holiness of God, not the minister, so that any properly ordained priest or bishop, even one in a state of mortal sin, is capable of administering a valid sacrament. This pertained not only the [[Eucharist]], which was administered on a weekly or even a daily basis, but also to [[baptism]]s, ordinations, [[marriage]]s, and last rites. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition to their theological and political differences with the Catholics, the Donatists also evolved a distinctive worship style, emphasizing what one commentator calls "mystical union of the righteous inspired by the Holy Spirit and instructed by the Bible."<ref>Murray, Stuart, [http://www.anabaptistnetwork.com/donatists The Donatists] ''www.anabaptistnetwork.com''. Retrieved February 12, 2008.</ref> In this they may have inherited some of the former zeal of an earlier heretical movement centered in Carthage, namely the [[Montanists]]. Indeed, the Donatists consciously drew from the writings of the pietist Church Father [[Tertullian]], who had been a Montanist in his later years, as well as his fellow Carthaginian, Saint [[Cyprian]], who had argued against the validity of [[heretical]] baptism. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The schism widens=== | ||

| + | Many towns were divided between Donatist and non-Donatist congregations. [[Constantine I|Constantine]], as emperor, soon involved himself in the dispute. His edict of 313 promised the Church of Africa his protection and favor, but not the Donatists. In 314 Constantine called a council at [[Arles]] in [[France]]. The issue was debated, and the decision went against the Donatists. Already suspicious of cooperation between the Church and the Empire, the Donatists refused to accept the decision. After Donatus was officially deposed as bishop by a council headed by the [[Bishop of Rome]], the Donatists uncharacteristically appealed directly to the Emperor. At Milan in 316, Constantine ruled that Cæcilianus, not Donatus, was the rightful Bishop of [[Carthage]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 317 Constantine ordered the confiscation of Donatist churches in [[Carthage]] and the death penalty on those who disturbed the peace. Constantine's actions resulted in [[banishment]]s and even [[execution]]s when violence erupted. It also failed completely, as the Donatists grew all the more fierce in their convictions. By 321 Constantine changed his approach and granted toleration to the Donatists, asking the catholic bishops to show them moderation and patience. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Edward Armitage - Julian the Apostate presiding at a conference of sectarian - 1875.jpg|thumb|300px|Julian the Apostate, depicted at a conference with "sectarians," possibly including Donatists.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Constantine's son, [[Constans]], launched a new wave of persecutions. The [[Circumcellions]], radical Donatists mainly of the peasant classes, resisted in violent opposition. By the time Cæcilianus died in 345, all hope of peaceful reconciliation of the Donatists and Catholics had passed. Constans succeeded in repressing the movement to some degree, and Donatus himself was banished. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The accession of [[Julian the Apostate]], however, relaxed the restrictions against the Donatists, as Julian sought to encourage those who opposed the Catholics' power. Although Donatus had by this time died, Julian appointed Parmenianus, a Donatist, as the official Bishop of Carthage. | ||

| − | + | For a time, between 372 and 375, the [[Roman usurper|usurper]] [[Firmus (4th century usurper)|Firmus]] ruled an independent government in North Africa and strongly supported the Donatists, while repressing the Catholics. After his revolt was put down, however, more laws against the Donatists were issued by Emperor [[Valentinian I]]. | |

| − | + | ===Fifth century developments=== | |

| + | [[Image:Simone Martini 003.jpg|thumb|125px|left|Augustine of Hippo was a vehement opponent of the Donatists.]] | ||

| + | In the early fifth century Saint [[Augustine of Hippo|Augustine]] campaigned strongly against the Donatist belief throughout his tenure as Bishop of Hippo, and through his efforts the Catholic Church gained the upper hand theologically. His view was that it was the office of [[priest]], not the personal character of the office-holder, that gave validity to the celebration of the [[sacrament]]s. Augustine's writings also provided a justification for the state's use of violence to intervene on behalf of [[orthodoxy]], a view which was put to much use by the medieval Church in its various campaigns against [[heresy]]. | ||

| − | + | In 409, [[Marcellinus of Carthage]], Emperor [[Honorius (emperor)|Honorius]]' Secretary of State, decreed the group heretical and demanded that they give up their churches. The [[Council of Carthage]] in 411 featured a large gathering of both Catholic and Donatist bishops. Augustine himself was one of the main spokesmen of the former, and the council declared that those who had been baptized in the name of the [[Trinity]] must not be re-baptized, regardless of the character the the priest performing the sacrament. The imperial commissioner decreed the Donatists to be banned, and severe measures were taken against them. After losing their civil rights in 414, they were forbidden to assemble for worship the next year, under penalty of death. | |

| − | + | Honorius' successes in putting down the Donatists, however, were reversed when the [[Vandals]] conquered [[North Africa]]. Donatism survived both the Vandal occupation and the [[Byzantine Empire|Byzantine]] reconquest under [[Justinian I]]. It persisted even into the [[Muslim]] period, during which it finally disappeared. | |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | {{readout||right|250px|The Donatists were the first [[Christian]] movement to oppose the union of [[church and state]]}} | ||

| + | Although the Donatists died out as a movement, they left a lasting impact on Christian tradition. They were the first Christian movement to oppose the union of [[church and state]] and they challenged mainstream Christianity to come to grips with the issue of whether it was going to be "holy" or "universal." In responding to the challenge of Donatism, the [[Catholic Church]] firmly established the principle that the Church is not only for saints but also for sinners. As a result, it further developed the tradition of the [[sacrament]]s of [[confession]] and [[penance]], enabling those who had committed serious sins after [[baptism]] to receive [[absolution]] and enter into full [[communion]]. At the same time, it established the principle that even sinful priests could dispense valid sacraments. Although this may have been necessary theologically, it had the unfortunate side effect of creating a basis for corrupt priests and bishops to operate with relative impunity, a tradition which plagues the Catholic Church to this day. | ||

| − | + | Later, [[Anabaptist]]s and other Protestant traditions have looked to Donatists as historical predecessors because of their opposition to the union of [[Church and state]], their emphasis on discipleship, and their opposition to the corruption within the Catholic hierarchy. | |

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | *Baker, Al. [http://www.churchhistory101.com/feedback/constantine-against-donatists.php Is it true that Emperor Constantine led an army of Christians against the Donatists in 316 C.E.?] ''Early Church History - CH101'', January 17, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2020. | ||

| + | *Benedict, David. ''History of the Donatists''. The Baptist Standard Bearer, 2001. ISBN 978-1579789954 | ||

| + | *Frend, W. H. C. ''The Donatist Church: A Movement of Protest in Roman North Africa''. Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0198264088 | ||

| + | *Tilley, Maureen A. ''Donatist Martyr Stories: The Church in Conflict in Roman North Africa''. Liverpool University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0853239314 | ||

| + | *Willis, Geoffrey. ''Saint Augustine and the Donatist Controversy''. Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2005. ISBN 978-1597521420 | ||

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| + | All links retrieved January 30, 2024. | ||

| − | [[ | + | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05121a.htm Donatists] ''www.newadvent.org.'' |

| + | *[http://www.biblestudytools.com/history/sketches-of-church-history/ad-33-604/st-augustine-ad-354-430-part-i.html Saint Augustine] ''bible.crosswalk.com''. | ||

| + | *[http://www.earlychurch.org.uk/donatism.php Donatus & the Donatist Schism] ''www.earlychurch.org.uk''. | ||

| − | + | [[category:history]] | |

| + | [[category:religion]] | ||

| + | [[category:Christianity]] | ||

| + | [[category:Islam]] | ||

| − | + | {{credits|77644556}} | |

Latest revision as of 17:23, 30 January 2024

The Donatist movement was a branch of Christianity in north Africa, eventually deemed heretical, which began in the early fourth century C.E. and flourished for more than a century, surviving numerous persecutions by the new Christian Roman Empire until it finally disappeared in the wake of the Muslim conquest.

The movement that would later be called Donatism originated in the African capital of Carthage, during the last great persecution of the Christian church by Emperor Diocletian in 303-305 C.E. The early Donatists were characterized by a determination to face martyrdom rather than cooperate with the Roman authorities who sought to force Christians to surrender their holy scriptures and other sacred objects. They refused to recognize as bishop a leader whose mentor had cooperated with Rome and had ordered Christians not to seek martyrdom. The schism is dated as beginning in 311, when the Donatists appointed a rival bishop instead. The movement takes it name from this bishop's successor, Donatus, who remained a bishop at Carthage, although occasionally forced into exile, until his death in 355.

After Constantine the Great legalized and supported the Christian faith, the Donatists declared that priests and bishops who had cooperated with Rome during the persecutions could not administer valid sacraments to their congregations. The movement spread throughout the Roman Empire and precipitated a widespread crisis as many "lapsed" priests returned to the fold to take advantage of the church's new found favor. The emperors generally supported the Catholic view that sacraments performed by sinful priests were still valid. Violent state repression of the Donatists failed to force them into submission in northern Africa, where they were often in the majority. Donatism survived into the sixth century and beyond, fading away only in the wake of the Muslim conquest.

The Donatist schism helped define the orthodox Church as "Catholic" (or Universal) and at the same time cemented an alliance between the church and the state which justified the use of state force against "heresy," a doctrine which lasted until the modern era. Some Protestant movements look to the Donatists as an example of opposition against the corruption of Catholicism and a pioneer in the struggle to achieve the separation of church and state.

Background

The Donatist movement's roots can be found in the persecution of the Christian church under Emperor Diocletian. On February 24, 303, the Emperor banned the Christian religion and commanded both the destruction of the churches and the burning of Christian scriptures. In 304, he issued an edict declaring that Christians must be willing to offer incense at the altars of the state or face capital punishment. Many Christians met their death as a result. Some—eager for martyrdom—willingly informed authorities that they were Christians or even that they possessed sacred scriptures but refused to give them up.

The persecution lasted only a brief time in Africa but it was particularly severe there. Mensurius, the Bishop of Carthage, forbade intentional martyrdom and admitted to handing over what he called "heretical" scriptures to the authorities while supposedly hiding legitimate scriptures in his home. His archdeacon, Cæcilianus, reportedly physically prevented the Carthaginian Christians from gathering for worship. On the other hand, Secundus, the leading bishop of Numidia, praised the martyrs who had been put to death for refusing to deliver up the scriptures. He declared himself "not a traditor"—a term referring to those who had cooperated with authorities by giving them either holy scriptures, sacred church vessels, or the names and persons of fellow Christians. Some of the Christians of Carthage and other cities broke off relations with Mensurius, considering him, rightly or wrongly, a traditor.

By 305 the persecution had abated, and a church council, or synod, was held at the Numidian city of Cirta. Bishop Secundus launched an investigation to ensure that there were no traditors present.

Shockingly, it was determined that most of the bishops fell under one definition or another of the term. When Mensurius died in 311, his protegé, Cæcilianus, succeeded him at Carthage. Secundus now convened another synod, and when Cæcilianus failed to appear to defend himself, he was deposed and excommunicated. The synod elected Majorinus in his place as Bishop of Carthage. When Majorinus himself soon died in 313, his successor would be Donatus. It is from this Donatus—characterized as a eloquent, learned leader of unbending faith—that the schism received its name.

Carthage now had two bishops and two competing congregations. The schism soon spread throughout the whole province, with a majority of the people, as well as a sizable number of bishops, supporting Donatus. Outside of Africa, however, the bishops generally recognized Cæcilianus.

The Donatist churches

Theological issues

The Donatists' primary disagreement with the mainstream church was over the question of the legitimacy of sacraments dispensed by traditors and other lapsed priests. Under the Emperor Constantine, the issue became particularly intense, as many fallen-away priests returned to the church to take advantage of the favored positions they would now have under Constantine's protection and support. The Donatists, however, proclaimed that any sacraments celebrated by these lapsed priests and bishops were invalid.

Two theological questions now confronted the Church as a result of the schism. The first was whether the sacrament of penance can bring an apostate Christian, specifically the traditor, into full communion. The Catholic answer was "yes." The Donatists, on the other hand, held that such a serious crime rendered one unfit for further membership in the Church. Indeed, the term Catholic (universal) came into frequent use during this time to express the universality of the orthodox position versus the more narrow insistence on holiness expressed by the Donatists.

The second question was the validity of sacraments conferred by priests and bishops who had fallen away. The Donatists held that such sacraments were not valid. By their sinful act, lapsed clerics had rendered themselves incapable of celebrating Christ's holy sacraments. The Catholic position was that the validity of the sacrament depends upon the holiness of God, not the minister, so that any properly ordained priest or bishop, even one in a state of mortal sin, is capable of administering a valid sacrament. This pertained not only the Eucharist, which was administered on a weekly or even a daily basis, but also to baptisms, ordinations, marriages, and last rites.

In addition to their theological and political differences with the Catholics, the Donatists also evolved a distinctive worship style, emphasizing what one commentator calls "mystical union of the righteous inspired by the Holy Spirit and instructed by the Bible."[1] In this they may have inherited some of the former zeal of an earlier heretical movement centered in Carthage, namely the Montanists. Indeed, the Donatists consciously drew from the writings of the pietist Church Father Tertullian, who had been a Montanist in his later years, as well as his fellow Carthaginian, Saint Cyprian, who had argued against the validity of heretical baptism.

The schism widens

Many towns were divided between Donatist and non-Donatist congregations. Constantine, as emperor, soon involved himself in the dispute. His edict of 313 promised the Church of Africa his protection and favor, but not the Donatists. In 314 Constantine called a council at Arles in France. The issue was debated, and the decision went against the Donatists. Already suspicious of cooperation between the Church and the Empire, the Donatists refused to accept the decision. After Donatus was officially deposed as bishop by a council headed by the Bishop of Rome, the Donatists uncharacteristically appealed directly to the Emperor. At Milan in 316, Constantine ruled that Cæcilianus, not Donatus, was the rightful Bishop of Carthage.

In 317 Constantine ordered the confiscation of Donatist churches in Carthage and the death penalty on those who disturbed the peace. Constantine's actions resulted in banishments and even executions when violence erupted. It also failed completely, as the Donatists grew all the more fierce in their convictions. By 321 Constantine changed his approach and granted toleration to the Donatists, asking the catholic bishops to show them moderation and patience.

Constantine's son, Constans, launched a new wave of persecutions. The Circumcellions, radical Donatists mainly of the peasant classes, resisted in violent opposition. By the time Cæcilianus died in 345, all hope of peaceful reconciliation of the Donatists and Catholics had passed. Constans succeeded in repressing the movement to some degree, and Donatus himself was banished.

The accession of Julian the Apostate, however, relaxed the restrictions against the Donatists, as Julian sought to encourage those who opposed the Catholics' power. Although Donatus had by this time died, Julian appointed Parmenianus, a Donatist, as the official Bishop of Carthage.

For a time, between 372 and 375, the usurper Firmus ruled an independent government in North Africa and strongly supported the Donatists, while repressing the Catholics. After his revolt was put down, however, more laws against the Donatists were issued by Emperor Valentinian I.

Fifth century developments

In the early fifth century Saint Augustine campaigned strongly against the Donatist belief throughout his tenure as Bishop of Hippo, and through his efforts the Catholic Church gained the upper hand theologically. His view was that it was the office of priest, not the personal character of the office-holder, that gave validity to the celebration of the sacraments. Augustine's writings also provided a justification for the state's use of violence to intervene on behalf of orthodoxy, a view which was put to much use by the medieval Church in its various campaigns against heresy.

In 409, Marcellinus of Carthage, Emperor Honorius' Secretary of State, decreed the group heretical and demanded that they give up their churches. The Council of Carthage in 411 featured a large gathering of both Catholic and Donatist bishops. Augustine himself was one of the main spokesmen of the former, and the council declared that those who had been baptized in the name of the Trinity must not be re-baptized, regardless of the character the the priest performing the sacrament. The imperial commissioner decreed the Donatists to be banned, and severe measures were taken against them. After losing their civil rights in 414, they were forbidden to assemble for worship the next year, under penalty of death.

Honorius' successes in putting down the Donatists, however, were reversed when the Vandals conquered North Africa. Donatism survived both the Vandal occupation and the Byzantine reconquest under Justinian I. It persisted even into the Muslim period, during which it finally disappeared.

Legacy

Although the Donatists died out as a movement, they left a lasting impact on Christian tradition. They were the first Christian movement to oppose the union of church and state and they challenged mainstream Christianity to come to grips with the issue of whether it was going to be "holy" or "universal." In responding to the challenge of Donatism, the Catholic Church firmly established the principle that the Church is not only for saints but also for sinners. As a result, it further developed the tradition of the sacraments of confession and penance, enabling those who had committed serious sins after baptism to receive absolution and enter into full communion. At the same time, it established the principle that even sinful priests could dispense valid sacraments. Although this may have been necessary theologically, it had the unfortunate side effect of creating a basis for corrupt priests and bishops to operate with relative impunity, a tradition which plagues the Catholic Church to this day.

Later, Anabaptists and other Protestant traditions have looked to Donatists as historical predecessors because of their opposition to the union of Church and state, their emphasis on discipleship, and their opposition to the corruption within the Catholic hierarchy.

Notes

- ↑ Murray, Stuart, The Donatists www.anabaptistnetwork.com. Retrieved February 12, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baker, Al. Is it true that Emperor Constantine led an army of Christians against the Donatists in 316 C.E.? Early Church History - CH101, January 17, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- Benedict, David. History of the Donatists. The Baptist Standard Bearer, 2001. ISBN 978-1579789954

- Frend, W. H. C. The Donatist Church: A Movement of Protest in Roman North Africa. Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0198264088

- Tilley, Maureen A. Donatist Martyr Stories: The Church in Conflict in Roman North Africa. Liverpool University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0853239314

- Willis, Geoffrey. Saint Augustine and the Donatist Controversy. Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2005. ISBN 978-1597521420

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2024.

- Donatists www.newadvent.org.

- Saint Augustine bible.crosswalk.com.

- Donatus & the Donatist Schism www.earlychurch.org.uk.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.