Chuseok

| Chuseok | |

|---|---|

| |

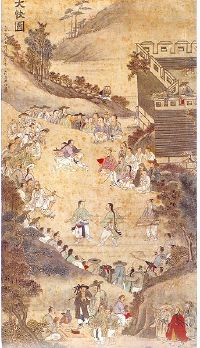

| Jesasang, ceremonial table setting on Chuseok. | |

| Official name | Chuseok (추석, 秋夕) |

| Also called | Hangawi, Jungchu-jeol |

| Observed by | Koreans |

| Type | Cultural, religious (Buddhist, Confucian, Muist) |

| Significance | Celebrates the harvest |

| Begins | 14th day of the 8th lunar month |

| Ends | 16th day of the 8th lunar month |

| Observances | Visit to their family's home town, ancestor worship, harvest feasts with songpyeon and rice wines |

| Related to | Mid-Autumn Festival (in China and Vietnam) Tsukimi (in Japan) Uposatha of Ashvini/Krittika (similar festivals that generally occur on the same day in Cambodia, India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand ) |

Chuseok (Korean: 추석; hanja: 秋夕), literally "Autumn eve," once known as hangawi (Korean: 한가위); from archaic Korean for "the great middle (of autumn)"), is a major harvest festival and a three-day holiday in both [North Korea|North]] and South Korea. It is celebrated on the 15th day of the eight month of the lunar calendar on the full moon. Like many other harvest festivals around the world, it is held around the autumn equinox at the very end of summer or early autumn.

As a celebration of the good harvest, Koreans visit their ancestral hometowns and share a feast of Korean traditional food such as songpyeon (Hangul: 송편) and rice wines. There are two major traditions related to Chuseok: Charye (차례), ancestor memorial services at home, and Seongmyo (Hangul: 성묘), family visit to the ancestral graves.

Origins

According to popular belief, Chuseok originates from gabae (Hangul: 가배). Gabae started during the reign of the third king of the kingdom of Silla (57 B.C.E. - 935 C.E.)[1]

Many scholars believe Chuseok may originate from shamanistic celebrations of the harvest moon.[1] New harvests are offered to local deities and ancestors, which means Chuseok may have originated as a worship ritual.

Traditional customs

Chuseok celebrates the bountiful harvest and strives for the next year to be better than the last. During this time the ancestors are honored, in special ceremonies.

Charye

Charye is one of the ancestral memorial rites celebrated during Chuseok, symbolizing the returning of favors and honoring ancestors and past generations.[2]

The rite involves the gathering of families in holding a memorial service for their ancestors through the harvesting, preparation, and presentation of special foods as offerings.[3] The rite embodies the traditional view of spiritual life beyond physical death, respecting the spirits of the afterlife that now also serve to protect their descendants.

The foods offered have traditionally varied across provinces depending on what was available. Foods for the offering table must include freshly harvested rice, alcohol, and songpyeon (half-moon rice cakes), prepared as an offering to the family’s ancestors.[4] The family members then enjoy a festive meal which may include japchae, bulgogi, an assortment of Korean pancakes, and fruits.

Seongmyo and Beolcho

Seongmyo, visiting the ancestors' graves, and Beolcho, cleaning the grave sites, are also done during Chuseok week. These old traditions are carried out to show respect and appreciation for family ancestors.

Usually people visit these ancestral grave sites several days before Chuseok in order to remove weeds that have grown there over the summer. This custom of Beolcho is considered a duty and an expression of devotion.[5]

During Seongmyo, family members gather at their ancestors' graves and pay respect to the deceased with a simple memorial service.

Food

Songpyeon

One of the major foods prepared and eaten during the Chuseok holiday is songpyeon (Hangul: 송편; 松편), a Korean traditional rice cake[4] stuffed with ingredients such as sesame seeds, black beans, mung beans, cinnamon, pine nut, walnut, chestnut, jujube, and honey. When making songpyeon, during the steaming process the rice cakes are layered with pine needles. The word song in songpyeon means pine tree in Korean. The pine needles form a pattern on the skin of songpyeon, and so contribute not only to their aroma and flavor but also to their beauty.[5][6]

Songpyeon is also significant because of the meaning contained in its shape. The round rice skin itself resembles the shape of a full moon, but once it is wrapped around the filling its shape resembles a half-moon. According to a Korean legend from the Three Kingdoms era, these two shapes ruled the destinies of the two greatest rival kingdoms, Baekje and Silla. During the era of King Uija of Baekje, an encrypted phrase, "Baekje is full-moon and Silla is half moon" was found on the back of a turtle and it predicted the fall of the Baekje and the rise of the Silla. The prophecy came true when Silla defeated Baekje. Ever since, Koreans have believed a half-moon shape is an indicator of a bright future or victory.[6] Therefore, during Chuseok', families gather together and eat half-moon-shaped songpyeon under the full moon, wishing for a brighter future.[5]

Hangwa

Another popular Korean traditional food that people eat during Chuseok is hangwa. Hangwa is made with rice flour, honey, fruit, and roots. People use edible natural ingredients to express various colors, flavors, and tastes. Decorated with natural colors and textured patterns, it is a festive confectionery. Koreans eat hangwa not only during Chuseok, but also for special events, such as weddings, birthday parties, and marriages.

The most famous types of hangwa are yakgwa, yugwa, and dasik. Yakgwa is a medicinal cookie which is made of fried rice flour dough ball, and yugwa is a fried cookie that also refers to a flower. Dasik is a tea cake that people enjoy with tea.[7]

Baekseju

A major element of Chuseok is the alcoholic beverages. At the memorial service for their ancestors, included in the offering of foods is also an alcoholic beverage made of the newly harvested rice. This traditional rice wine is called baekseju.

Gifts

A Chuseok tradition in modern-day Korea is that of gift-giving. Koreans will present gifts to not only their relatives, but also to friends and business acquaintances to show their thanks and appreciation.

In the 1960s Korean people started sharing daily necessities, such as sugar, soap, or condiments, as Chuseok gifts. As the Korean economy developed, options for Chuseok gifts also increased, to include cooking oil, toothpaste, instant coffee sets, cosmetics, television, and rice cookers. Gift sets of fruit, meat, traditional Korean snacks, and cosmetics became popular, as well as sets of olive oil, natural vinegar, ginger, fruits, mushrooms, and that Korean favorite, Spam, which are sold at high prices in the weeks before Chuseok.[8]

Folk games

A variety of folk games are played on Chuseok to celebrate the coming of autumn and the rich harvest. Village folk may dress themselves to resemble a cow or turtle, and go from house to house along with a nongak band playing music. Other common traditional games played on Chuseok include ssireum (Korean wrestling), Taekkyon, and juldarigi (tug-of-war).

Ssireum

Ssireum (Hangul: 씨름) is the most popular Korean sport played during Chuseok, and contests are usually held during this holiday. Ssireum is assumed to have 5000 years of history; scholars have found evidence for ssireums dating back to the Goguryeo dynasty,

Two players wrestle each other while holding onto their opponent's satba, a red and blue band. A player loses when his upper body touches the ground, and the winner becomes Cheonha Jangsa, Baekdu Jangsa, or Halla Jangsa, meaning "the most powerful." The winner gets a bull and 1 kg of rice as the prize.[9] Due to its popularity among both the young and the old, ssireum contests are held quite frequently, not limited to important holidays.

Taekkyon

Taekkyon (Hangul: 태껸 or 택견) is one of the oldest traditional martial arts of Korea. Taekkyon was very popular during the Joseon period where it was practiced alongside Ssireum during festivities, including Chuseok. Tournaments between players from different villages were carried out, starting with the children ("Aegi Taekkyon") and finishing with the adults.

Taekkyon is a hand-to-hand fighting method in which practitioners makes use of fluid, rhythmic dance-like movements to strike or trip up an opponent. The practitioner uses the momentum of his opponent to knock him down. Taekkyon is now considered a UNESCO intangible cultural heritage item (2011)[10].

Ganggangsullae

The Ganggangsullae (Hangul: 강강술래) dance is a traditional folk dance performed under the full moon on the night of Chuseok.[11] Women wear Korean traditional dress, hanbok, make a big circle by holding hands, and sing a song while going around a circle.

The dance originated in the southern coastal area during the Joseon dynasty. It takes its name from the refrain repeated after each verse, although the exact meaning of the word is unknown.[12]

For other folk games, they also play Neolttwigi (also known as the Korean plank), a traditional game played on a wooden board.[13]

Juldarigi

Juldarigi (Hangul: 줄다리기), or tug-of-war, was enjoyed by an entire village population. Two groups of people are divided into two teams representing the female and male forces of the natural world. The game is considered an agricultural rite to augur the results of the year's farming. If the team representing the female concept won, it was thought the harvest that year would be rich.

Chicken Fight (Dak Sa Um)

Korean people used to watch chicken fights, Dak Sa Um (Hangul: 닭싸움), and learned how chickens fought; a game inspired by such was invented.

To play the game, people are separated into two balanced groups. One must bend his or her leg up and hold it bent with the knee poking out. The players must then attack each other with their bent knees, having to eliminate them by making their feet touch the ground; the last player holding up his or her knee wins.

The game is about strength, speed, and balance; in order to stay alive, one must display the capability of fighting back.[14]

Hwatu

Hwatu (Hangul: 화투), or Go-Stop, is composed of 48 cards including 12 kinds. It originated from a Japanese card game called Hanafuda, and is the most popular card game played by Koreans today. The rules of the game and the term hwatu originated from Tujeon. Early hwatu was similar to Hanafuda, but was changed due to similarities with the latter. It went through a course that made it reduced by four base colors and thinner than before, spreading throughout to turn out goods on a mass-produced basis.

Contemporary Celebrations

South Korea

In contemporary South Korea, on Chuseok, masses of people travel from large cities to their hometowns to pay respect to the spirits of their ancestors.[4] People perform ancestral worship rituals early in the morning. Then, they visit the tombs of their immediate ancestors to trim plants and clean the area around the tomb, and offer food, drink, and crops to their ancestors.[4] South Koreans consider autumn the best season of the year due to clear skies, cool winds, and it is a perfect harvesting season. Harvest crops are attributed to the blessing of ancestors. Chuseok is commonly translated as "Korean Thanksgiving" in American English.[15] Although most South Koreans will be visiting their families and ancestral homes, there are festivities held at the National Folk Museum of Korea. Many places are closed during this national holiday including: banks, schools, post offices, governmental departments, stores, etc. Travel tickets are usually sold out three months in advance and roads and hotels are overcrowded.[16]

North Korea

Since Chuseok has been a traditional holiday since long before the division of Korea, people in North Korea also celebrate Chuseok. However, the ideology that divided Korea also caused some differences between Chuseok' of North Korea and that of South Korea.[17] Since the division, South Korea has adopted a westernized culture, so the way South Koreans enjoy the holiday is a typical way of enjoying holidays with family members. However, North Korea moved away from the traditional ways; in fact, North Korea did not celebrate Chuseok and other traditional holidays until the mid-1980s.

Though most North Koreans do not have any family gatherings during Chuseok, some, especially those in working classes, try to visit their ancestors's grave sites during Chuseok. However, social and economic issues in North Korea have been preventing visits.[18] In addition, their extremely poor infrastructure, especially in terms of public transportation, make it almost impossible for people to visit grave sites and their families.[19] In contrast to the poorly situated lower class North Koreans, middle and elite classes enjoy the holiday as they want, easily traveling wherever they want to go.[19]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Charles E. Farhadian, Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007, ISBN 0802828531).

- ↑ Korean Ancestral Memorial Rites, Jerye Korea4Expats. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ↑ Kimberly Comeau , A time for families, food and festivities The Jeju Weekly, September 12, 2011. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Traditional Korean Holiday of Bountiful Harvest, Chuseok Korea Tourism Organization, September 2, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2019. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "KTO" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Chuseok – Full Moon Harvest Holiday Korea Tourist Organization. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 No Chuseok Without Songpyeon Inside Korea, Chosunilbo, September 22, 2010. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ↑ Hangwa Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ↑ 10 Ridiculously Priced Korean Chuseok Gift Sets 10 Magazine. Retrieved October 11, 2019,

- ↑ Traditional Korean Sport - Ssireum What's on Korea, July 28, 2001. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ↑ Taekkyeon, a traditional Korean martial art UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ↑ Seoul City. (2004, September 2) {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}

- ↑ Ganggangsullae UNESCO Intangible Heritage. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ↑ Festivals, events to delight on Chuseok holidays. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Chuseok: Korean Thanksgiving Day. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Lee, Cecilia Hae-Jin (2010). Frommer's South Korea. Hoboken, N.J, Chichester: Wiley, John Wiley, 21, 22, 25. ISBN 0470591544.

- ↑ "Chuseok— A Festival With Two Faces", 10 September 2011.

- ↑ Archived copy.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Jin, Im Jeong (23 September 2010). Welcome to Chuseok, North Korean Style.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Farhadian, Charles E. Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007. ISBN 0802828531

- National Folk Museum of Korea (South Korea) Encyclopedia of Korean Seasonal Customs. Gil-Job-Ie Media, 2015. ASIN B019TYXACC

- The Academy of Korean Studies, ed. (1991), "Chuseok", Encyclopedia of Korean People and Culture, Woongjin (in Korean)

- Farhadian, Charles E. (2007). Christian Worship Worldwide. Wm. Bm. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2853-8.

- (1982) Korean Heritage Overview. Korea University. (in Korean)

- Aviles, K. (2011, September 10). Chuseok : A Festival With Two Faces. International Business Times. Retrieved December 4, 2012 Chuseok— A Festival With Two Faces 10 September 2011 International Business Times

- Im, J. J. (2010, September 23). Daily NK - Welcome to Chuseok, North Korean Style. DailyNK. Retrieved December 4, 2012 Welcome to Chuseok, North Korean Style Im Jeong Jin 23 September 2010 Dailynk.com </ref>

- Kim, K.-C. (2008). Ganggangsullae. UNESCO Multimedia Archives. Retrieved December 4, 2012 Ganggangsullae Kim Kwang-shik-CHA Unesco.org</ref>

- Korea.net. (2012, February 5). Chuseok, Korean Thanksgiving Day (English) - YouTube. YouTube. Retrieved December 4, 2012 Chuseok, Korean Thanksgiving Day (English)

- Moon, S. H. (2008, September 16). Daily NK - New Chuseok Trends in North Korea. DailyNK. Retrieved December 4, 2012

- Official Korea Tourism. (2008, August 26). Official Site of Korea Tourism Org.: Chuseok : Full Moon Harvest Holiday, Korean Version of Thanksgiving Day. VisitKorea. Retrieved December 4, 2012

- The National Folklore Museum of Korea. (n.d.). Ancestral Memorial Rites - Charye | The National Folklore Museum of Korea. The National Folklore Museum of Korea. Retrieved December 5, 2012 [http://www.nfm.go.kr/Data/cuThar.jsp 메세지 페이지 Nfm.go.kr

- TurtlePress (Martial Arts Video). (2009, May 1). SSireum Korean Wrestling History - YouTube. YouTube. Retrieved December 4, 2012 SSireum Korean Wrestling History

- Yoo, K. H. (2009, October 5). Chuseok, North Korean Style. DailyNK. Retrieved December 4, 2012 Chuseok, North Korean Style Yoo Gwan Hee Dailynk.com

External links

All links retrieved

- What Is Chuseok?

- Traditional Korean Holiday of Bountiful Harvest, Chuseok

- Chuseok, Korean Thanksgiving Day at YouTube

- How to Celebrate Chuseok in South Korea

- Chuseok (Harvest Moon Festival) 2019

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.