Difference between revisions of "Booker T. Washington" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

Born into slavery in Franklin County, Virginia, Washington lived the horrors of that system until the age of nine. It was then that he and his fellow blacks were emancipated. His mother and his stepfather then moved the family to [[Malden, West Virginia]], where young Booker learned to rudimentarily read and write, while working at manual labor jobs. At the age of sixteen, he journeyed 500 miles to [[Hampton, Virginia]], in order to enroll in the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute—now [[Hampton University]]—to be trained as a teacher. In 1881, the 25-year-old Washington was named as the first Principal of the [[Tuskegee Institute]] in [[Alabama]]. He was granted an honorary [[Master of Arts]] degree from [[Harvard University]] in 1896, and an honorary [[Doctorate]] degree from [[Dartmouth College]] in 1901. | Born into slavery in Franklin County, Virginia, Washington lived the horrors of that system until the age of nine. It was then that he and his fellow blacks were emancipated. His mother and his stepfather then moved the family to [[Malden, West Virginia]], where young Booker learned to rudimentarily read and write, while working at manual labor jobs. At the age of sixteen, he journeyed 500 miles to [[Hampton, Virginia]], in order to enroll in the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute—now [[Hampton University]]—to be trained as a teacher. In 1881, the 25-year-old Washington was named as the first Principal of the [[Tuskegee Institute]] in [[Alabama]]. He was granted an honorary [[Master of Arts]] degree from [[Harvard University]] in 1896, and an honorary [[Doctorate]] degree from [[Dartmouth College]] in 1901. | ||

| − | Washington obtained national prominence after his famous [[Atlanta Exposition Address]] of 1895. This speech garnered him widespread recognition by politicians, by academicians, and by the public at large, as the pre-eminent spokesperson for the uplift and advancement of American blacks. Simultaneously, a number of black critics on the intellectual Left vehemently excoriated him as an "accommodationist" and a "sell out," because of his de-emphasis on protest politics and his refusal to constantly berate white America | + | Washington obtained national prominence after his famous [[Atlanta Exposition Address]] of 1895. This speech garnered him widespread recognition by politicians, by academicians, and by the public at large, as the pre-eminent spokesperson for the uplift and advancement of American blacks. Simultaneously, a number of black critics on the intellectual Left vehemently excoriated him as an "accommodationist" and a "sell out," because of his de-emphasis on protest politics and his refusal to constantly berate white America for its racial sin and guilt. The racially hostile culture notwithstanding, Washington's commitment was to the ideal of peaceful coexistence between blacks and whites. In practice, this meant reaching out to white people and enlisting the support of wealthy philanthropists, whose donations supplied the funds to establish and operate dozens of small community schools and institutions of higher education for the betterment of blacks throughout [[the South]]. |

| − | In addition to his substantial contributions in the fields of both industrial and academic education, Dr. Washington's proactive leadership raised to a new dimension the nation's awareness of how an oppressed people group can uplift itself through creative and persistent interior activism via self-help and entrepreneurial business development. He taught that if blacks would cease replaying the sins of the past and, instead, remain focused on the goal of fostering groupwide, economic stability, then the subsequent respect educed from whites would lead to an atmosphere much more conducive to the resolution of America's race problems. Many blacks who embraced these ideas came to believe that they were playing a major role in the effort to effect better overall friendships and business relations between themselves and their white fellow Americans. | + | In addition to his substantial contributions in the fields of both industrial and academic education, Dr. Washington's proactive leadership raised to a new dimension the nation's awareness of how an oppressed people-group can uplift itself through creative and persistent interior activism via self-help and entrepreneurial business development. He taught that if blacks would cease replaying the sins of the past and, instead, remain focused on the goal of fostering groupwide, economic stability, then the subsequent respect educed from whites would lead to an atmosphere much more conducive to the resolution of America's race problems. Many blacks who embraced these ideas came to believe that they were playing a major role in the effort to effect better overall friendships and business relations between themselves and their white fellow Americans. |

| − | Washington's autobiography, ''[[Up From Slavery]]'', first published in 1901, is still widely read. Other important writings include ''[[The Future of the Negro]] | + | Washington's autobiography, ''[[Up From Slavery]]'', first published in 1901, is still widely read. Other important writings include ''[[The Future of the Negro]]'', (1902); ''[[The Story of the Negro]]'', (1909); and ''[[The Man Farthest Down]]'', (1912). |

==Youth, freedom and education== | ==Youth, freedom and education== | ||

Revision as of 22:20, 27 July 2006

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856 – November 14, 1915) was an African American political leader, educator and author. From 1890 to 1915, his vision, program, strategy, and leadership skills propelled him to the forefront of America's quest to forge racial success from an historical environment of racial failure and hatred. The success so urgently needed was required at both the intraracial level and the interracial level.

Intraracially, millions of propertyless, illiterate, and resentful Southern freedmen needed an action plan by which to rise up from poverty, ignorance, and humiliation. Interracially, millions of hostile, defeated, and intransigent Southern whites needed liberation from their historical hatred, guilt, and fear, so that, eventually, unity between whites and blacks might take place throughout America. From within this highly volatile and chaotic setting emerged Booker T. Washington, a former slave, who determined to take responsibilty for helping his country fulfill its creed, as articulated in the Declaration of Independence.

Born into slavery in Franklin County, Virginia, Washington lived the horrors of that system until the age of nine. It was then that he and his fellow blacks were emancipated. His mother and his stepfather then moved the family to Malden, West Virginia, where young Booker learned to rudimentarily read and write, while working at manual labor jobs. At the age of sixteen, he journeyed 500 miles to Hampton, Virginia, in order to enroll in the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute—now Hampton University—to be trained as a teacher. In 1881, the 25-year-old Washington was named as the first Principal of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. He was granted an honorary Master of Arts degree from Harvard University in 1896, and an honorary Doctorate degree from Dartmouth College in 1901.

Washington obtained national prominence after his famous Atlanta Exposition Address of 1895. This speech garnered him widespread recognition by politicians, by academicians, and by the public at large, as the pre-eminent spokesperson for the uplift and advancement of American blacks. Simultaneously, a number of black critics on the intellectual Left vehemently excoriated him as an "accommodationist" and a "sell out," because of his de-emphasis on protest politics and his refusal to constantly berate white America for its racial sin and guilt. The racially hostile culture notwithstanding, Washington's commitment was to the ideal of peaceful coexistence between blacks and whites. In practice, this meant reaching out to white people and enlisting the support of wealthy philanthropists, whose donations supplied the funds to establish and operate dozens of small community schools and institutions of higher education for the betterment of blacks throughout the South.

In addition to his substantial contributions in the fields of both industrial and academic education, Dr. Washington's proactive leadership raised to a new dimension the nation's awareness of how an oppressed people-group can uplift itself through creative and persistent interior activism via self-help and entrepreneurial business development. He taught that if blacks would cease replaying the sins of the past and, instead, remain focused on the goal of fostering groupwide, economic stability, then the subsequent respect educed from whites would lead to an atmosphere much more conducive to the resolution of America's race problems. Many blacks who embraced these ideas came to believe that they were playing a major role in the effort to effect better overall friendships and business relations between themselves and their white fellow Americans.

Washington's autobiography, Up From Slavery, first published in 1901, is still widely read. Other important writings include The Future of the Negro, (1902); The Story of the Negro, (1909); and The Man Farthest Down, (1912).

Youth, freedom and education

Booker T. Washington was born April 5 1856 on the Burroughs farm at the community of Hale's Ford. His mother Jane was a cook and his father was a white man from a nearby farm. He recalled emancipation in early 1865: [Up from Slavery 19-21]

As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom… Some man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper — the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see.

In the summer of 1865, at the age of nine, Booker and his brother John and his sister, Amanda, moved to Malden in Kanawha County, West Virginia with their mother to join his stepfather. He worked with his mother and other free blacks as a salt-packer and in a coalmine. He even signed up briefly as a hired hand on a steamboat. However, soon he became employed as a houseboy for Viola (née Knapp) Ruffner, the wife of General Lewis Ruffner, who owned the salt-furnace and coalmine. Many other houseboys had failed to satisfy the demanding and methodical Mrs. Ruffner, but Booker's diligence and attention to detail met her standards. Encouraged to do so by Mrs. Ruffner, when he could, young Booker attended school and learned to read and to write. And soon, he sought even more education than was available in his community.

Leaving Malden at sixteen, Washington enrolled at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, in Hampton, Virginia. Poor students such as Washington could get a place there by working to pay their way. The normal school at Hampton was founded for the purpose of training black teachers and had been largely funded by church groups and individuals such as William Jackson Palmer, a Quaker, among others. In many ways he was back where he had started, earning a living through menial tasks, but his time at Hampton led him away from a life of labor. From 1878 to 1879 he attended Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., and returned to teach at Hampton. Soon, Hampton officials recommended him to become the first principal of a similar school being founded in Alabama.

Tuskegee

Former slave Lewis Adams and other organizers of a new normal school in Tuskegee, Alabama sought a bright and energetic leader for their new school. They at first anticipated employing a white administrator, but instead, they found the desired qualities in 25 year-old Booker T. Washington. Upon the strong recommendation of Hampton University founder Samuel C. Armstrong, Washington became the first principal of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, which opened on July 4, 1881. The new school later developed into the Tuskegee Institute and is now Tuskegee University.

Tuskegee provided an academic education and instruction for teachers, but placed more emphasis on providing young black boys with practical skills such as carpentry and masonry. The institute illustrates Washington's aspirations for his race. His theory was, that by providing these skills, African Americans would play their part in society and this would lead to acceptance by white Americans. He believed that African Americans would eventually gain full Civil Rights by showing themselves to be responsible, reliable American citizens.

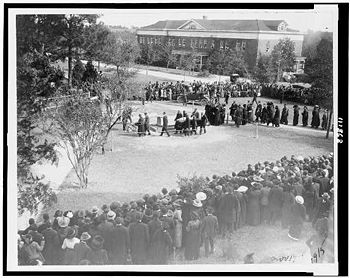

Still an important center for African-American learning in the 21st century, according to its website, Tuskegee Institute was created "to embody and enable the goals of self-reliance." These themes were fundamental to the rest of Washington's life and work over a period of more than thirty additional years. He was principal of the school until his death in 1915. At his death, Tuskegee's endowment had grown to over $1.5 million from the initial $2,000 annual appropriation obtained by Lewis Adams and his supporters.

Family

Washington was married three times. In his autobiography Up From Slavery, he gave all three of his wives enormous credit for their work at Tuskegee and was emphatic that he would not have been successful without them.

Fannie N. Smith was from Malden, West Virginia, the same Kanawha River Valley town located eight miles upriver from Charleston where Washington had lived from age nine to sixteen (and maintained ties throughout his later life). Washington and Smith were married in the summer of 1882. They had one child, Portia M. Washington. Fannie died in May 1884.

He next wed Olivia A. Davidson in 1885. Davidson was born in Ohio, spent time teaching in Mississippi and Tennessee and received her education at Hampton Institute and the Massachusetts State Normal School at Framingham. Washington met Davidson at Tuskegee, where she had come to teach. She later became the assistant principal there. They had two sons, Booker T. Washington Jr. and Ernest Davidson Washington, before she died in 1889.

His third marriage took place in 1893 to Margaret James Murray. She was from Mississippi and was a graduate of Fisk University. They had no children together. Murray outlived Washington and died in 1925.

Politics

Active in politics, Booker T. Washington was routinely consulted by Republican Congressmen and Presidents about the appointment of African Americans to political positions. He worked and socialized with many white politicians and notables. He argued that self-reliance was the key to improved conditions for African Americans in the United States and that they could not expect too much, having only just been granted emancipation.

His 1895 Atlanta Compromise address, given at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, sparked a controversy wherein he was cast as an accommodationist among those who heeded Frederick Douglass' call to "Agitate, Agitate, Agitate" for social change. A public debate soon began between those such as Washington, who valued the so-called "industrial" education and those who, like W.E.B. DuBois, supported the idea of a "classical" education among African-Americans. Both sides sought to define the best means to improve the conditions of the post-Civil War African-American community. Washington's advice to African-Americans to "compromise" and accept segregation, incensed other activists of the time, such as DuBois, who labeled him "The Great Accommodator". It should be noted, however, that despite not condemning Jim Crow laws and the inhumanity of lynching publicly, Washington privately contributed funds for legal challenges against segregation and disfranchisement, such as his support in the case of Giles v. Harris, which went before the United States Supreme Court in 1903.

Although early in DuBois' career the two were friends and respected each other considerably, their political views diverged to the extent that after Washington's death, DuBois stated "In stern justice, we must lay on the soul of this man a heavy responsibility for the consummation of Negro disfranchisement, the decline of the Negro college and public school, and the firmer establishment of color caste in this land."

Rich friends and benefactors

Washington associated with the richest and most powerful businessmen and politicians of the era. He was seen as a spokesperson for African Americans and became a conduit for funding educational programs. His contacts included such diverse and well-known personages as Andrew Carnegie, William Howard Taft, and Julius Rosenwald, to whom he made the need for better educational facilities well-known. As a result, countless small schools were established through his efforts, in programs that continued many years after his death.

Henry Rogers

A representative case of an exceptional relationship was his friendship with millionaire industrialist Henry H. Rogers (1840-1909), a self-made man who had risen to become a principal of Standard Oil. Around 1894, Rogers heard Washington speak and was surprised that no one had "passed the hat" after the speech. The next day, he contacted Washington and requested a meeting, beginning a close relationship that was to extend over a period of 15 years.

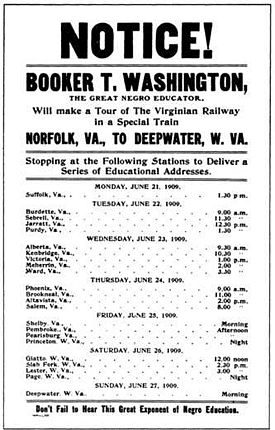

In June 1909, a few weeks after Rogers died, Washington went on a previously planned speaking tour along the newly completed Virginian Railway. He rode in Rogers' personal rail car, "Dixie", making speeches at many locations over a 7-day period. He told his audiences that his goal was to improve relations between the races and economic conditions for African Americans along the route of the new railway, which touched many previously isolated communities in the southern portions of Virginia and West Virginia. He revealed that Rogers had been quietly funding operations of 65 small country schools for African Americans, and gave substantial sums of money to support Tuskegee Institute and Hampton Institute. Rogers encouraged program with matching funds requirements so the recipients would have a stake in knowing that they were helping themselves through their own hard work and sacrifice.

Anna T. Jeanes

$1,000,000 was entrusted to him by Anna T. Jeanes (1822-1907) of Philadelphia in 1907. She was a woman who hoped to construct some elementary schools for Negro children in the South. Her contributions and those of Henry Rogers and others funded schools in many communities where the white people were also very poor, and few funds were available for Negro schools.

Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932) was another self-made wealthy man with whom Dr. Washington found common ground. In 1908, Rosenwald became president of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Rosenwald was concerned about the poor state of African American education, especially in the South. In 1912 Rosenwald was asked to serve on the Board of Directors of Tuskegee Institute, a position he held for the remainder of his life. Rosenwald endowed Tuskegee so that Dr. Washington could spend less time traveling to seek funding and devote more time towards management of the school. Later in 1912, Rosenwald provided funds for a pilot program involving six new small schools in rural Alabama, which were designed, constructed and opened in 1913 and 1914 and overseen by Tuskegee; the model proved successful. Rosenwald established the The Rosenwald Fund. The school building program was one of its largest programs. Using state-of-the-art architectural plans initially drawn by professors at Tuskegee Institute [1], the Rosenwald Fund spent over four million dollars to help build 4,977 schools, 217 teachers' homes, and 163 shop buildings in 883 counties in 15 states, from Maryland to Texas. The Rosenwald Fund used a system of matching grants, and black communities raised more than $4.7 million to aid the construction [2]. These schools became known as Rosenwald Schools. By 1932, the facilities could accommodate one third of all African American children in Southern schools.

Up from Slavery, invitation to the White House

In an effort to inspire the "commercial, agricultural, educational, and industrial advancement" of African Americans, Booker T. Washington founded the National Negro Business League (NNBL) in 1900.

When his autobiography, Up From Slavery, was published in 1901, it became a bestseller and had a major impact on the African American community, and its friends and allies. Washington in 1901 was the first African-American ever invited to the White House as the guest of President Theodore Roosevelt – white Southerners complained loudly.

The hard-driving Washington finally collapsed in Tuskegee, Alabama due to a lifetime of overwork and died soon after in a hospital, on November 14, 1915. In March of 2006, with the permission of his family, examination of medical records indicated that he died of hypertension, with a blood pressure more than twice normal. He is buried on the campus of Tuskegee University near the University Chapel.

Honors and memorials

For his contributions to American society, Dr. Washington was granted an honorary Masters of Arts degree from Harvard University in 1896 and an honorary Doctorate degree from Dartmouth College in 1901. The first coin to feature an African-American was the Booker T. Washington Memorial Half Dollar that was minted by the United States from 1946 to 1951. On April 7, 1940, Dr. Washington became the first African American to be depicted on a United States postage stamp. On April 5, 1956, the house where he was born in Franklin County, Virginia was designated as the Booker T. Washington National Monument. Additionally, numerous schools across the United States are named for him (M.S.54). A state park in Chattanooga, TN names in his honor, as is a bridge adjacent to his alma mater, Hampton University, across the Hampton River in Hampton, Virginia.

At the center of the campus at Tuskegee University, the Booker T. Washington Monument, called "Lifting the Veil," was dedicated in 1922. The inscription at its base reads:

- "He lifted the veil of ignorance from his people and pointed the way to progress through education and industry."

Quotes

- "Think about it: We went into slavery pagans; we came out Christians. We went into slavery pieces of property; we came out American citizens. We went into slavery with chains clanking about our wrists; we came out with the American ballot in our hands...Notwithstanding the cruelty and moral wrong of slavery, we are in a stronger and more hopeful condition, materially, intellectually, morally, and religiously, than is true of an equal number of black people in any other portion of the globe."

- Booker T. Washington, from Up From Slavery

- "I will let no man drag me down so low as to make me hate him."

- Booker T. Washington

- "There is another class of colored people who make a business of keeping the troubles, the wrongs, and the hardships of the Negro race before the public. Having learned that they are able to make a living out of their troubles, they have grown into the settled habit of advertising their wrongs — partly because they want sympathy and partly because it pays. Some of these people do not want the Negro to lose his grievances, because they do not want to lose their jobs."

- Booker T. Washington

- "It is at the bottom of life we must begin, not at the top."

- Booker T. Washington

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources

- Washington, Booker T. The Awakening of the Negro, The Atlantic Monthly, 78 (September, 1896).

- Up from Slavery: An Autobiography (1901).

- Washington, Booker T. The Atlanta Compromise (1895).

- The Booker T. Washington Papers University of Illinois Press online version of complete fourteen volume set of all letters to and from Booker T. Washington.

Secondary sources

- James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935 (1988)

- Mark Bauerlein. Washington, Du Bois, and the Black Future" in Wilson Quarterly (Autumn 2004).

- W. Fitzhugh Brundage, ed Booker T. Washington and Black Progress: Up from Slavery 100 Years Later (2003).

- Louis R. Harlan, Booker T. Washington: The Making of a Black Leader, 1856-1900 (1972) the standard biography, vol 1.

- Louis R. Harlan. Booker T. Washington: The Wizard of Tuskegee 1901-1915 (1983), the standard scholarly biography vol 2.

- Louis R. Harlan. Booker T. Washington in Perspective: Essays of Louis R. Harlan (1988).

- Louis R. Harlan. "The Secret Life of Booker T. Washington." thirty seven Journal of Southern History 393 (1971). in JSTOR Documents Booker T. Washington's secret financing and directing of litigation against segregation and disfranchisement.

- Linda O. Mcmurry. George Washington Carver, Scientist and Symbol (1982)

- August Meier. "Toward a Reinterpretation of Booker T. Washington." twenty three Journal of Southern History 220 (1957) in JSTOR. Documents Booker T. Washington's secret financing and directing of litigation against segregation and disfranchisement.

- Cary D. Wintz, African American Political Thought, 1890-1930: Washington, Du Bois, Garvey, and Randolph (1996).

See also

- Slave narrative, African American literature.

- Rabbit's foot - Washington's association with one of the earliest recorded stories of a "lucky rabbit's foot" in an American newspaper.

External links

- Booker T. Washington's West Virginia Boyhood a good website with details of his youth before going to Hampton

- Works by Booker T. Washington. Project Gutenberg

- Up from Slavery, Project Gutenberg edition

- Up from Slavery, Electronic Edition

- The Awakening of the Negro

- The Case of the Negro

- Booker T. Washington's 1909 Tour of Virginia on the newly completed Virginian Railway

- Dr. Booker T. Washington papers - comments about Henry Rogers

- National Park Service Booker T. Washington Birthplace

- Legends of Tuskegee

- Booker T. Washington from Answers.com

- Booker T. Washington's Gravesite

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Washington, Booker T. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Washington, Booker Taliaferro |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | educator |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 5, 1856 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hale's Ford, Franklin County, Virginia, United States of America |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 15, 1915 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Tuskegee, Alabama, United States of America |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.