Difference between revisions of "Beltane" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since the early 20th century it has been commonly accepted that [[Old Irish]] ''Beltaine'' is derived from a [[Common Celtic]] ''*belo-te(p)niâ'', meaning "bright fire". The element ''*belo-'' might be cognate with the English word ''bale'' (as in 'bale-fire') meaning 'white' or 'shining'; compare [[Old English]] ''bael'', and [[Lithuanian language|Lithuanian]]/[[Latvian language|Latvian]] ''baltas/balts'', found in the name of the [[Baltic Sea|Baltic]]; in [[Slavic languages]] ''byelo'' or ''beloye'' also means 'white', as in ''Беларусь'' ([[White Russia]] or [[Belarus]]) or ''Бе́лое мо́ре'' ([[White Sea]]). A more recent etymology by Xavier Delamarre would derive it from a Common Celtic ''*Beltinijā'', cognate with the name of the Lithuanian goddess of death ''[[Giltinė]]'', the root of both being [[Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European]] ''*gʷelH-'' ("suffering, death").<ref>Delamarre, Xavier. Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, Editions Errance, Paris, 2003, p. 70</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Ó Duinnín's Irish dictionary (1904), Beltane is referred to as ''Céadamh(ain)'' which it explains is short for ''Céad-shamh(ain)'' meaning "first (of) summer". The dictionary also states that ''Dia Céadamhan'' is May Day and ''Mí Céadamhan'' is the month of May. | ||

| + | |||

The word ''Beltane'' derives directly from the [[Old Irish]] ''Beltain'', which later evolved into the [[Irish language|Modern Irish]] ''Bealtaine'' (pr. 'byol-tana'). In [[Scottish Gaelic]] it is spelled ''Bealltainn''.<ref name="SMO"> ''[http://www.smo.uhi.ac.uk/gaidhlig/faclair/sbg/lorg.php?facal=Bealltainn&seorsa=Gaidhlig&tairg=Lorg&eis_saor=on Stòr-dàta Briathrachais Gàidhlig - Rùachadh]''. Sabhal Mòr Ostaig —Colaiste Ghàidhlig na h-Alba </ref> Both are from Old Irish ''Beltene'' ('bright fire') from ''belo-te(p)niâ''. Beltane was formerly spelled 'Bealtuinn' in Scottish Gaelic; in Manx it is spelt 'Boaltinn' or 'Boaldyn'. | The word ''Beltane'' derives directly from the [[Old Irish]] ''Beltain'', which later evolved into the [[Irish language|Modern Irish]] ''Bealtaine'' (pr. 'byol-tana'). In [[Scottish Gaelic]] it is spelled ''Bealltainn''.<ref name="SMO"> ''[http://www.smo.uhi.ac.uk/gaidhlig/faclair/sbg/lorg.php?facal=Bealltainn&seorsa=Gaidhlig&tairg=Lorg&eis_saor=on Stòr-dàta Briathrachais Gàidhlig - Rùachadh]''. Sabhal Mòr Ostaig —Colaiste Ghàidhlig na h-Alba </ref> Both are from Old Irish ''Beltene'' ('bright fire') from ''belo-te(p)niâ''. Beltane was formerly spelled 'Bealtuinn' in Scottish Gaelic; in Manx it is spelt 'Boaltinn' or 'Boaldyn'. | ||

Revision as of 21:40, 13 November 2013

| Beltane | |

|---|---|

| Also called | Lá Bealtaine, Bealltainn, Beltain, Beltaine |

| Observed by | Gaels, Irish People, Scottish People, Manx people, Neopagans |

| Type | Pagan |

| Date | Northern Hemisphere: May 1 Southern Hemisphere: November 1 |

| Celebrations | Traditional first day of summer in Ireland, Scotland and Isle of Man |

| Related to | Walpurgis Night, May Day |

Beltane (pronounced /ˈbɛltən/) is the anglicized spelling of Bealtaine or Bealltainn, the Gaelic names for either the month of May or the festival that takes place on the first day of May.

In Irish Gaelic the month of May is known as Mí Bealtaine or Bealtaine and the festival as Lá Bealtaine ('day of Bealtaine' or, 'May Day'). In Scottish Gaelic the month is known as either (An) Cèitean or a' Mhàigh, and the festival is known as Latha Bealltainn or simply Bealltainn. The feast was also known as Céad Shamhain or Cétshamhainin from which the word Céitean derives.

As an ancient Gaelic festival, Bealtaine was celebrated in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. There were similar festivals held at the same time in the other Celtic countries of Wales, Brittany and Cornwall. Bealtaine and Samhain were the leading terminal dates of the civil year in Ireland though the latter festival was the most important. The festival survives in folkloric practices in the Celtic Nations and the diaspora, and has experienced a degree of revival in recent decades.

Overview

For the Celts, Beltane marked the beginning of the pastoral summer season when the herds of livestock were driven out to the summer pastures and mountain grazing lands. Due to the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar, Bealltainn in Scotland was commonly celebrated on May 15 while in Ireland Sean Bhealtain / "Old May" began about the night of May 11.[citation needed] The lighting of bonfires on Oidhche Bhealtaine ('the eve of Bealtaine') on mountains and hills of ritual and political significance was one of the main activities of the festival.[1][2] In modern Scottish Gaelic, Latha Buidhe Bealtuinn ('the yellow day of Bealltain') is used to describe the first day of May. This term Lá Buidhe Bealtaine is also used in Irish and is translated as 'Bright May Day'. In Ireland it is referred to in a common folk tale as Luan Lae Bealtaine; the first day of the week (Monday/Luan) is added to emphasise the first day of summer.

In ancient Ireland the main Bealtaine fire was held on the central hill of Uisneach 'the navel of Ireland', one of the ritual centres of the country, which is located in what is now County Westmeath. In Ireland the lighting of bonfires on Oidhche Bhealtaine seems only to have survived to the present day in County Limerick, especially in Limerick itself, as their yearly bonfire night, though some cultural groups have expressed an interest in reviving the custom at Uisneach and perhaps at the Hill of Tara.[3] The lighting of a community Bealtaine fire from which individual hearth fires are then relit is also observed in modern times in some parts of the Celtic diaspora and by some Neopagan groups, though in the majority of these cases this practice is a cultural revival rather than an unbroken survival of the ancient tradition.[4][5][1][6]

Another common aspect of the festival which survived up until the early 20th century in Ireland was the hanging of May Boughs on the doors and windows of houses and the erection of May Bushes in farmyards, which usually consisted either of a branch of rowan/caorthann (mountain ash) or more commonly whitethorn/sceach geal (hawthorn) which is in bloom at the time and is commonly called the 'May Bush' or just 'May' in Hiberno-English. Furze/aiteann was also used for the May Boughs, May Bushes and as fuel for the bonfire. The practice of decorating the May Bush or Dos Bhealtaine with flowers, ribbons, garlands and colored egg shells has survived to some extent among the diaspora as well, most notably in Newfoundland, and in some Easter traditions observed on the East Coast of the United States.[1]

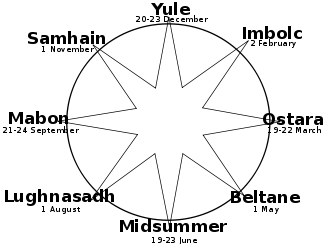

Bealtaine is a cross-quarter day, marking the midpoint in the Sun's progress between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Since the Celtic year was based on both lunar and solar cycles, it is possible that the holiday was celebrated on the full moon nearest the midpoint between the spring equinox and the summer solstice. The astronomical date for this midpoint is closer to May 5 or May 7, but this can vary from year to year.[7]

Placenames in Ireland which contain remnants of the word 'Bealtaine' include a number of places called 'Beltany' - indicating places where Bealtaine festivities were once held. There are two 'Beltany's in County Donegal, one near Raphoe and the other in the parish of Tulloghobegly. Two others are located in County Tyrone, one near Clogher and the other in the parish of Cappagh. In the parish of Kilmore, County Armagh, there is a place called Tamnaghvelton/Tamhnach Bhealtaine ('field of the Bealtaine festivities'). Lisbalting/Lios Bealtaine ('fort or enclosure of Bealtaine') is located in Kilcash Parish, County Tipperary. Glasheennabaultina ('the Bealtaine stream') is the name of a stream joining the River Galey near Athea, County Limerick.

Origins

In Irish mythology, the beginning of the summer season for the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Milesians started at Bealtaine. Great bonfires would mark a time of purification and transition, heralding in the season in the hope of a good harvest later in the year, and were accompanied with ritual acts to protect the people from any harm by Otherworldly spirits, such as the Aos Sí. Like the festival of Samhain, which is celebrated on October 31 which is opposite Beltane in the year, Beltane was a time when the Otherworld was seen as particularly close at hand.

Early Gaelic sources from around the 10th century state that the druids of the community would create a need-fire on top of a hill on this day and drive the village's cattle through the fires to purify them and bring luck (Eadar dà theine Bhealltainn in Scottish Gaelic, 'Between two fires of Beltane'). This term is also found in Irish and is used as a turn of phrase to describe a situation which is difficult to escape from. In Scotland, boughs of juniper were sometimes thrown on the fires to add an additional element of purification and blessing to the smoke. People would also pass between the two fires to purify themselves. This was echoed throughout history after Christianization, with lay people instead of Druid priests creating the need-fire. The festival persisted widely up until the 1950s, and in some places the celebration of Beltane continues today.[4][8][9]

In Wales, the day is known as Calan Mai, and the Gaulish name for the day is Belotenia.[10]

Etymology

Since the early 20th century it has been commonly accepted that Old Irish Beltaine is derived from a Common Celtic *belo-te(p)niâ, meaning "bright fire". The element *belo- might be cognate with the English word bale (as in 'bale-fire') meaning 'white' or 'shining'; compare Old English bael, and Lithuanian/Latvian baltas/balts, found in the name of the Baltic; in Slavic languages byelo or beloye also means 'white', as in Беларусь (White Russia or Belarus) or Бе́лое мо́ре (White Sea). A more recent etymology by Xavier Delamarre would derive it from a Common Celtic *Beltinijā, cognate with the name of the Lithuanian goddess of death Giltinė, the root of both being Proto-Indo-European *gʷelH- ("suffering, death").[11]

In Ó Duinnín's Irish dictionary (1904), Beltane is referred to as Céadamh(ain) which it explains is short for Céad-shamh(ain) meaning "first (of) summer". The dictionary also states that Dia Céadamhan is May Day and Mí Céadamhan is the month of May.

The word Beltane derives directly from the Old Irish Beltain, which later evolved into the Modern Irish Bealtaine (pr. 'byol-tana'). In Scottish Gaelic it is spelled Bealltainn.[12] Both are from Old Irish Beltene ('bright fire') from belo-te(p)niâ. Beltane was formerly spelled 'Bealtuinn' in Scottish Gaelic; in Manx it is spelt 'Boaltinn' or 'Boaldyn'.

In Modern Irish, Oidhche Bealtaine or Oíche Bealtaine is May Eve, and Lá Bealtaine is May Day. Mí na Bealtaine, or simply Bealtaine is the name of the month of May

In the word belo-te(p)niâ) the element belo- is cognate with the English word bale (as in 'bale-fire'), the Anglo-Saxon bael, and also the Lithuanian baltas, meaning 'white' or 'shining' and from which the Baltic Sea takes its name.

In Gaelic the terminal vowel -o (from Belo) was dropped, as shown by numerous other transformations from early or Proto-Celtic to Early Irish, thus the Gaulish deity names Belenos ('bright one') and Belisama.

From the same Proto-Celtic roots we get a wide range of other words: the verb beothaich, from Early Celtic belo-thaich ('to kindle, light, revive, or re-animate'); baos, from baelos ('shining'); beòlach ('ashes with hot embers') from beò/belo + luathach, ('shiny-ashes' or 'live-ashes'). Similarly boil/boile ('fiery madness'), through Irish buile and Early Irish baile/boillsg ('gleam'), and bolg-s-cio-, related to Latin fulgeo ('shine'), and English 'effulgent'.

According to the Gaelic scholar Dáithí Ó hÓgáin Céad Shamhain or Cétshamhainin means "first half," which he links to the Gaulish word samonios (which he suggest means "half a year") as in the end of the "first half" of the year that begins at Samhain. According to Ó hÓgáin this term was also used in Scottish Gaelic and Welsh. In Ó Duinnín's Irish dictionary it is referred to as Céadamh(ain) which it explains is short for Céad-shamh(ain) meaning "first (of) summer." The dictionary also states that Dia Céadamhan is May Day and Mí Céadamhan is May

Revival

Neopagan

Beltane is observed by Neopagans in various forms, and by a variety of names. As forms of Neopaganism can be quite different and have very different origins, these representations can vary considerably despite the shared name. Some celebrate in a manner as close as possible to how the Ancient Celts and Living Celtic cultures have maintained the traditions, while others observe the holiday with rituals taken from numerous other unrelated sources, Celtic culture being only one of the sources used.[13][14]

Celtic Reconstructionist

Like other Reconstructionist traditions, Celtic Reconstructionist Pagans place emphasis on historical accuracy. They base their celebrations and rituals on traditional lore from the living Celtic cultures, as well as research into the older beliefs of the polytheistic Celts.[15]

Celtic Reconstructionists usually celebrate Lá Bealtaine when the local hawthorn trees are in bloom, or on the full moon that falls closest to this event. Many observe the traditional bonfire rites, to whatever extent this is feasible where they live, including the dousing of the household hearth flame and relighting of it from the community festival fire. Some decorate May Bushes and prepare traditional festival foods. Pilgrimages to holy wells are traditional at this time, and offerings and prayers to the spirits or deities of the wells are usually part of this practice. Crafts such as the making of equal-armed rowan crosses are common, and often part of rituals performed for the blessing and protection of the household and land.[15][16][17]

Wicca

Wiccans and Wiccan-inspired Neopagans celebrate a variation of Beltane as a sabbat, one of the eight solar holidays. Although the holiday may use features of the Gaelic Bealtaine, such as the bonfire, it bears more relation to the Germanic May Day festival, both in its significance (focusing on fertility) and its rituals (such as maypole dancing). Some Wiccans celebrate 'High Beltaine' by enacting a ritual union of the May Lord and Lady.[18]

Among the Wiccan sabbats, Beltane is a cross-quarter day; it is celebrated in the northern hemisphere on May 1 and in the southern hemisphere on November 1. Beltane follows Ostara and precedes Midsummer.[18]

Beltane Fire Festival in Edinburgh

Beltane Fire Festival is an annual participatory arts event and ritual drama, held on April 30 on Calton Hill in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is inspired by the ancient Gaelic festival of Beltane which marked the beginning of summer.[19] The modern festival was started in 1988 by a small group of enthusiasts, with academic support from the School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh. Since then the festival has grown, with an audience of around 12 thousand people sharing the spectacular procession.

The main event of the festival is the procession of performers, starting at the Acropolis (National Monument), who perform a ritual drama loosely based on some aspects of the pre-Christian festival of Beltane, and other mythologies from ancient cultures. The fertility of the land and animals is celebrated and encouraged. Led by one of the Blue Men, the procession's guides and guards, the Green Man (in winter guise) appears through the columns. Next the Need Fire is made; this is the making of fire by traditional methods, and all fire seen on the night is produced from this first flame. The Torchbearers and Processional Drummers are next over the top of the Acropolis, followed by the White Warrior Women and finally the May Queen. A horn signals the May Queen's birth, and the drums begin. The May Queen and her White Women, four of whom are her Handmaidens, proceed to be born of the Earth, greet the (four) cardinal directions in back bends and bow to the crowd of spectators (in three directions). After they finally acknowledge the Earth and the sky, the Green Man (who has been watching this from the ground) is allowed to approach the May Queen at the very top. She accepts him as her consort and the procession begins, led by the May Queen. The four Handmaidens, White Women bodyguards and Processional Drummers then join the May Queen and Green Man, and all are flanked by Torchbearers and Stewards and guided and protected by four Blue Men onto one of the footpaths running along the top of Calton Hill.

The footpath reaches an intersection, and the May Queen spins to decide which direction to turn in, choosing the leftward path which leads to the Fire Arch. Between the intersection and Arch, the Handmaidens and White Women stir the air with their wands, gathering the energies of the Earth, while the Drummers change rhythms to indicate the difference in purpose.

At the Fire Arch, the Guardians first greet the May Queen and Green Man, and perform a dance which represents the rituals necessary to open a path into the Underworld. As the procession passes through the Fire Arch, the Handmaidens and White Women begin to keen, mourning the losses of the world over the past year. This continues until the procession reaches the Point of the Element of Air.

At the Air Point, performers representing the element of Air put on a display for the May Queen and Green Man and present them with a gift. Having awakened Air, the May Queen leads the procession through the point and around the side of the hill to the Earth Point, which is situated in the midst of a stand of trees on the North-eastern side of Calton Hill. More dancers and acrobats perform for the May Queen and Green Man, and they are presented with a bannock bread before the procession continues again, passing through the point and around to Water Point, on the Northern side of the hill with a view overlooking the Firth of Forth. Again a ritual performance occurs here, including the washing of the May Queen and Green Man's faces in the "dew." After this point's gift is presented the procession heads on to Fire Point.

Again, dancers and acrobats perform and offer the May Queen and Green Man a gift. The procession wends its way down the side of the hill to a lower footpath, where the Handmaidens and White Women begin gathering the energies of the awakening Earth and sending them deep into the hill. The procession pauses below the City Observatory to watch the Fire Point display on the hillside above and another gift is presented.

Once awakened by the power of the May Queen the Elements do not follow the procession but are drawn towards each other and move from their "points" towards a place where they can gather and unify, thus restoring the natural order.

Having awakened the four elements, the May Queen guides the procession around the Western side of the hill. The first of the Red Men, imps created with the May Queen's appearance at the Monument and representing the forces of Chaos, spot the procession as it passes below and are attracted to the May Queen and her Warriors. As the procession rounds the hill, the Red Men begin to taunt the White Women, and then stage a series of charges as the procession reaches the base of the hill on the South side of the Observatory. This represents the Red Men's interest in capturing the May Queen on behalf of their their lord the Green Man. The White Women ward the Red Men off in the end without 'killing' any of them as any unnecessary 'deaths' would lead to a lessening of the energies needed to bring about the change of the seasons from Winter to Summer.

The procession completes a full circle, arriving back at the path intersection, and turns to cross over the top of the hill and down into a valley where a stage has been set up for the final display. The Handmaidens perform a ritual to 'cleanse' the stage while the Torchbearers, Stewards and White Women form a circle around the open space surrounding the stage. The May Queen and Green Man mount the stage and the May Queen begins her ritual to awaken the Earth to summertime.

While she and her Handmaidens and the White Women begin to spin and focus the energies they have been gathering throughout the night, the Red Men are allowed to approach the stage and circle it, increasing the power further. Overcome with the May Queen's beauty and goaded by the presence of the Red Men, the Green Man can no longer resist and catches the May Queen. This act is strictly forbidden, and the Green Man is ritually killed by the Handmaidens, lifted and turned anticlockwise, his bulky Winter form stripped away and thrown to the Red Men, he is then turned clockwise and presented to the May Queen.

The May Queen takes pity on the Green Man and brings him back to life, like a young sapling breaking the earth after Winter's hoarfrost is melted away. Overwhelmed by the new life that fills him the Green Man dances presenting himself to the four directions, repeating the actions of the May Queen from the beginning of the procession.

The May Queen then crowns the Green Man and leads the procession up the hill to the bonfire, on a high Northern point overlooking the valley on the hill and the city of Edinburgh below. The White Women and Red Men surround the bonfire (making an outer and middle layer respectively) with the Handmaidens forming the innermost layer. A set of wax hands are then lit and the May Queen and the Green Man make their way into the very centre of the Reds and Whites. They walk around the bonfire with the lit wax hands three times, on the fourth circuit they light the bonfire with the flaming hands in four places. They then walk thrice more around the bonfire as the Beltane blessing is announced to the gathered people. The lighting of the bonfire signals the end of Winter and the coming of Summer, and the Green Man's Winter form is symbolically cast into the pyre. At the same time the stage is occupied by Fire Point, this symbolises the old tradition where farmers would drive their herds between two bonfires at this time of year to bless them.

Once the bonfire is lit, the procession passes through the crowds to the May Queen's Bower, on the side of the hill below and behind the Acropolis, where the procession can finally relax. The Fire Arch Guardians formally present their gift to the May Queen and Green Man, and Handfastings are held as the couples are blessed and jump together over the Willow-switch withies of the Blue Men, representing a commitment which will last through all trials for a year and a day.

After this, the four Elements and other groups (these vary but will usually include "No Point," that entertain spectators without being in a fixed location) formally present their gifts to the May Queen and Green Man, and the Red Men are presented before the Handmaidens and White Women. Symbolically, they seduce/are seduced by the White Women and Handmaidens, representing a union between the White Order and the Red Chaos. The rest of the performers are then invited into the Bower circle to dance and celebrate the arrival of summer, and finally so are the spectators.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Danaher, Kevin (1972) The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs Dublin, Mercier. ISBN 1-85635-093-2 pp.86-127

- ↑ Chadwick, Nora (1970) The Celts London, Penguin. ISBN 0-14-021211-6 p. 181

- ↑ Aideen O'Leary reports ("An Irish Apocryphal Apostle: Muirchú's Portrayal of Saint Patrick" The Harvard Theological Review 89.3 [July 1996:287-301] p. 289) that, for didactic and dramatic purposes, the festival of Beltane, as presided over by Patrick's opponent King Lóegaire mac Néill, was moved to the eve of Easter and from Uisneach to Tara by Muirchú (late seventh century) in his Vita sancti Patricii; he describes the festival as in Temora, istorium Babylone ('at Tara, their Babylon'). However there is no authentic connection of Tara with Babylon, nor any know connection of Tara with Beltane.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 MacKillop, James (1998) A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280120-1 pp.39, 400-402, 421

- ↑ Dames, Michael (1992) Mythic Ireland. London, Thames & Hudson ISBN 0-500-27872-5. p.206-10

- ↑ McNeill, F. Marian (1959) The Silver Bough, Vol. 2. William MacLellan, Glasgow ISBN 0-85335-162-7 p.56

- ↑ Dames (1992) p.214

- ↑ McNeill (1959) Vol. 2. p.63

- ↑ Campbell, John Gregorson (1900, 1902, 2005) The Gaelic Otherworld. Edited by Ronald Black. Edinburgh, Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 1-84158-207-7 p.552-4

- ↑ MacKillop (1998) p.39

- ↑ Delamarre, Xavier. Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, Editions Errance, Paris, 2003, p. 70

- ↑ Stòr-dàta Briathrachais Gàidhlig - Rùachadh. Sabhal Mòr Ostaig —Colaiste Ghàidhlig na h-Alba

- ↑ Adler, Margot (1979) Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston, Beacon Press ISBN 0-8070-3237-9. p.3

- ↑ McColman, Carl (2003) Complete Idiot's Guide to Celtic Wisdom. Alpha Press ISBN 0-02-864417-4. p.51

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 McColman (2003) pp.12, 51

- ↑ Bonewits, Isaac (2006) Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism. New York, Kensington Publishing Group ISBN 0-8065-2710-2. p.130-7

- ↑ Healy, Elizabeth (2001) In Search of Ireland's Holy Wells. Dublin, Wolfhound Press ISBN 0-86327-865-5 p.27

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Starhawk (1979, 1989) The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. New York, Harper and Row ISBN 0-06-250814-8 pp.181-196 (revised edition)

- ↑ Beltane, Beltane Fire Society, 2007. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carmichael, Alexander. Carmina Gadelica. Lindisfarne Press, 1992. ISBN 0940262509

- Chadwick, Nora. The Celts. London: Penguin, 1970. ISBN 0140212116

- Danaher, Kevin. The Year in Ireland. Dublin: Mercier, 1972. ISBN 1856350932

- Evans-Wentz, W. Y. The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries. New York, NY: Citadel, 1990. ISBN 0806511605

- MacKillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0192801201

- McNeill, F. Marian. Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Vols. 1-4. Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990. ISBN 0948474041

- Cabot, Laurie, and Jean Mills. Celebrate the Earth: A Year of Holidays in the Pagan Tradition. New York, NY: Dell Publishing, 1994. ISBN 0385309201

- Hamilton, Claire. Celtic Book of Seasonal Meditations: Celebrate the Traditions of the Ancient Celts. York Beach, ME: Red Wheel/Weiser, 2003. ISBN 1590030559

- Dames, Michael. Mythic Ireland. London, Thames & Hudson, 1992. ISBN 0500278725

- Campbell, John Gregorson, and Ronald Black. The Gaelic Otherworld. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd., 2005. ISBN 1841582077

- Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1981. ISBN 0807032379

- McColman, Carl. Complete Idiot's Guide to Celtic Wisdom. Alpha Press, 2003. ISBN 0028644174

- Bonewits, Isaac. Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism. New York, NY: Kensington Publishing Group, 2006. ISBN 0806527102

- Starhawk. The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess, 2nd rev. ed. New York, Harper and Row, 1989. ISBN 0062508148

- Healy, Elizabeth. In Search of Ireland's Holy Wells. Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 2001. ISBN 0863278655

External links

- Edinburgh's Beltane Fire Society

- Extract on The Beltane Fires from Sir James George Frazer's book The Golden Bough - 1922

- Beltane Fire Society - The official BFS website

- Night Watch - The Torchbearers and Stewards of Beltane

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.