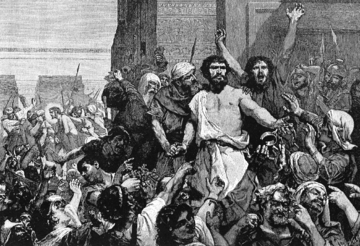

Barabbas

Barabbas was the Jewish insurrectionist whom Pontius Pilate freed at the Passover feast in Jerusalem in the Christian narrative of the Passion of Jesus. According to some texts, his full name was Yeshua bar Abba, (Jesus, the "son of the father").

The penalty for Barabbas' crime of treason against Rome—the same crime for which Jesus was also convicted—was death by crucifixion. However, according to the four canonical gospels and the Gospel of Peter, there was a prevailing Passover custom in Jerusalem that allowed or required Pilate to commute one prisoner's death sentence by popular acclaim. The crowd was offered a choice of whether to have Barabbas or Jesus released from Roman custody. According to the closely parallel gospels of Matthew (27:15-26), Mark (15:6-15), Luke (23:13–25), and the more divergent accounts in John (18:38-19:16), the crowd chose for Barabbas to be released and Jesus of Nazareth to be crucified. A passage found only in the Gospel of Matthew[1] has the crowd saying, "Let his blood be upon us and upon our children."

The story of Barabbas has special social significances, partly because it has frequently been used to lay the blame for the Crucifixion on the Jews and justify anti-Semitism. The story may also have served to shift blame away from the Roman state, removing an impediment to Christianity's acceptance.

Background

Barabbas lived during a time when the independent Jewish state established by the Hasmonean dynasty had been brought to end by the unrivaled power of the Roman Empire. The Hasmoneans themselves were considered corrupt by strict religious Jews, and Jewish client kings such as Herod the Great created an atmosphere of widespread resentment. The two mainstream religious parties, the Sadducees and Pharisees, came to represent opposing poles, with the Sadducees generally controlling the Temple priesthood and the Sadducees appealing to a more popular piety. Consequently, the Sadducees came to be seen as Roman collaborators, while the Pharisees themselves were divided in the attitude toward Roman rule. In this context, the group known to history as the Zealots arose as a party of passionate opposition to Rome, willing to use violence against these foreign oppressors to hasten the coming of the Messiah.

Barabbas' crime

John 18:40 refers to Barabbas as a lēstēs, "bandit;" Mark and Luke further refer to Barabbas as one involved in a stasis, a riot. Mark 15:7; Luke 23:19. Matthew refers to Barabbas only as a "notorious prisoner." Matthew 27:16. Some scholars[attribution needed] posit that Barabbas was a member of the sicarii, a militant Jewish movement that sought to overthrow the Roman occupiers of their land by force, noting that Mark (15:7) mentions that he had committed murder in an insurrection.

The sicarii and the ongoing revolt of Jews against foreign presence in Judea have been discussed by Robert Eisenman;[2] however, many historians maintain that the sicarii only arose in the 40s or 50s of the first century—after Jesus' execution.[3]

Various authors contend Barabbas's crime would translate today as terrorism.[4][5][6]. Some however, have argued that he was a freedom fighter campaigning for autonomy from Roman imperialism. He is called a terrorist in the Contemporary English Version of the Bible.[7][8]

Barabbas in the gospels

Three gospels all state unequivocally that there was a custom at Passover during which the Roman governor would release a prisoner of the crowd's choice: Mark 15:6; Matt. 27:15; John 18:39. The corresponding verse in Luke (Luke 23:17) is not present in the earliest manuscripts and may be a later gloss to bring Luke into conformity.[9] The gospels differ on whether the custom was a Roman one or a Jewish one. Such a release or custom of such a release is not recorded in any other historical document.[10]

A possible parable

This practice of releasing a prisoner is said by Magee and others to be an element in a literary creation of Mark, who needed to have a contrast to the true "son of the father" in order to set up an edifying contest, in a form of parable. An interpretation, using modern reader response theory, suggests no petition for the release of Barabbas need ever have happened at all, and that the contrast between Barabbas and Jesus is a parable meant to draw the reader (or hearer) of the gospel into the narrative so that they must choose whose revolution, the violent insurgency of Barabbas or the challenging gospel of Jesus, is truly from the Father.[11].[12]

Dennis R. MacDonald, in the The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark, notes that a similar episode to the one that occurs in Mark- of a crowd picking one figure over another figure similar to the other occurred in The Odyssey, where Odysseus entered the palace disguised as a beggar and defeated a real beggar to reclaim his throne[13]. MacDonald suggests Mark borrowed from this section of The Odyssey and used it to pen the Barabbas tale, only this time Jesus- the protagonist- loses to highlight the cruelness of Jesus' persecutors[14]. However, this theory too is rejected by mainstream scholars. [15]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Matthew 27:25.

- ↑ Eisenman, James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls

- ↑ Brown, Raymond E. (1994).The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave: A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels v.1 pp. 688-92. New York: Doubleday/The Anchor Bible Reference Library. ISBN 0-385-49448-3<; Meier, John P. (2001). A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, v. 3, p. 210. New York: Doubleday/The Anchor Bible Reference Library. ISBN 0-385-46993-4 (v.3).

- ↑ Travis, Stephen H. (2004). The Bible in Time: An exploration of 130 passages providing an overview of the Bible as a whole. Clements Publishing, 200. ISBN 1894667476.

- ↑ Boice, James Montgomery and Philip Graham Ryken (2002). Jesus on Trial. Crossway Books, 79. ISBN 1581344015.

- ↑ McBride, Alfred A. and Virginia C. Holmgren, O. Praem (1998). To Love and Be Loved by Jesus. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing, 113. ISBN 087973356X.

- ↑ Bible Gateway Contemporary English Version, Matthew 27:16.

- ↑ Bible Gateway Contemporary English Version, John 18:40.

- ↑ Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave: A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels v.1. pp 793-95. New York: Doubleday/The Anchor Bible Reference Library. ISBN 0-385-49448-3.

- ↑ Philip A. Cunningham, Executive Director. Death of Jesus. Boston College: Christian-Jewish Learning at Boston College.

- ↑ Whitehouse, Mary. The Mystery Of Barabbas: Exploring the Origins of a Pagan Religion. United Kingdom: Ask Why Publications. ISBN 0-9521913-1-8.

- ↑ Magee, Michael. The Hidden Jesus. United Kingdom: Ask Why Publications. ISBN 0-9521913-2-6.

- ↑ Jesus and Barabbas

- ↑ Jesus and Barabbas

- ↑ Ibid. The Death of the Messiah pp.811-14

External links

- John Dominic Crossan, "Crowd control": identity, purpose and size of "the crowd" in Mark and its adapted purposes in Luke and John, on the occasion of the Mel Gibson film of 2004.

- More on the interpretation that Jesus and Barabbas were the same person

- Why Barabbas Was Released Instead of Jesus

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.