Anointing

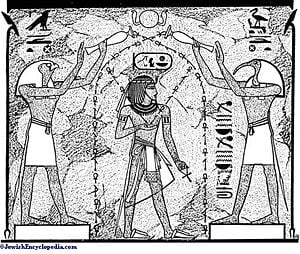

Anointing, also called Unction is the lubrication of an item or body body, often the head, with perfumed oil, animal fat, or melted butter. The process is employed ritually by many religions and ethnic groups. People and objects are anointed to symbolize the introduction of a sacramental or divine influence, a holy emanation, spirit, or power. Anointing can also be seen as a spiritual mode of ridding persons and things of dangerous influences and diseases, especially of demons.

Anointing has also been used as part of the coronation ceremonies of kings, symbolizing divine blessing upon the monarch. In Hebrew, the term of an "anointed one" is meshiach, from which the term "Messiah" is derived. The Greek word for Messiah is "Christ."

In Christian tradition, anointing oil may be called chrism. Formerly known as "extreme unction,' the sacrament of the anointing of the sick should not be confused with "last rights,' which includes not only unction, but also confession and penance.

Antecedents

The indigenous Australians believed that the virtues of a slain beast could be transferred to survivors if they rubbed themselves with his intestinal-fat. Similarly, the Arabs of East Africa anointed themselves with lion's fat in order to gain courage and inspire the animals with awe.

Human fat is considered to be a powerful charm all over the world. The fat was often considered to be the vehicle and seat of life, second only to the blood. This, in addition to the "pleasing odor" produced, resulting in the fat of a sacrificial animal victim being smeared on a sacred altar to honor to the deity.

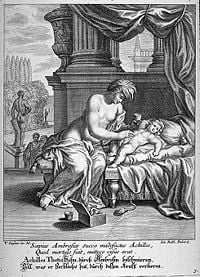

According to some beliefs, the qualities of divinity can, by anointing, be transferred into men as well. In Greek mythology the goddess Thetis anointed her mortal child Achilles with ambrosia in order to make him immortal, famously neglecting to anoint his heel.

Among the Jews, as among other peoples, kings were anointed with olive oil in token of God's blessing upon them. Butter is often used for anointing in the Hindu religion. A newly built house is smeared with it; so are those believed to be suffering from demonic possession, care being taken to smear the latter downwards from head to foot. Anointments are also part of certain Hindu monarchies' enthronement ritual, when blood can also be used.

Hebrew Bible

Among the Hebrews, the act of anointing was significant in consecration a person or object to a sacred use. The Bible thus speaks of the anointing of the high priest (Exodus 29:29; Leviticus 4:3) and of the sacred vessels (Exodus 30:26).

In the Hebrew Bible, the high priest and the king are both sometimes called "the anointed" (Leviticus 4:3-5, 4:16; 6:20; Psalm 132:10). Prophets were also sometimes anointed (1 Kings 19:16; 1 Chronicles 16:22; Psalm 105:15).

Anointing a king was equivalent to crowning him in terms of authority. In fact, in Israel, a crown was not required (1 Samuel 16:13; 2 Samuel 2:4, etc.). Thus David was anointed as king by the prophet Samuel:

- Then Samuel took the horn of oil, and anointed him in the midst of his brethren: and the Spirit of the Lord came upon David from that day forward. So Samuel rose up, and went to Ramah.—1 Samuel 16:13.

The terms "Messiah" and "Christ" are English and Greek versions of the Hebrew Mashiach, meaning "anointed one," originally referring to the Messiah's position as a Davidic king who would restore the ideal of the Israelite monarchy centered on God's law.

It was the custom of the Jews in like manner to anoint themselves with oil, as a means of refreshing or invigorating their bodies (Deuteronomy 28:40; Ruth 3:3; 2 Samuel 14:2; Psalms 104:15, etc.). The Hellenes had similar customs. This custom is continued among the Arabs to the present day. The expression, "anoint the shield" (Isaiah 21:5), refers to the custom of rubbing oil on the leather of the shield so as to make it supple and fit for use in war. Oil was used also for medicinal purposes. It was applied to the sick, and also to wounds (Psalms 109:18; Isaiah 1:6.

In the New Testament

Christians particularly emphasize the idea of the "anointed one" referring to the promised Messiah in various biblical verses such as Psalm 2:2 and Daniel 9:25-26. The word Christ, which is now used as though it were a surname, is actually a title derived from the Greek Christos, meaning "anointed," and constituting a Greek version of the his title "the Messiah."

Jesus, however, is understood in Christianity to be "anointed" not through any physical substance or human agency, such as a priest or prophet, by virtual of his predestined messiahship. However, the Gospels do state that Jesus was physically "anointed" by an anonymous woman who is interpreted by some as Mary Magdalene, and also by Mary of Bethany, just prior to his death. Anointing was also an act of hospitality, as Jesus was anointed in the house of the Pharisee (Luke 7:38-46).

In the Book of Acts, the imparting of the Holy Spirit to believers came to be associated sometimes with baptism and also with a separate experience of receiving the Holy Spirit through the gift of "tongues."

The New Testament also records that oil was applied to the sick, and also to wounds Mark 6:13; James 5:14). The bodies of the dead were also sometimes anointed (Mark 14:8; Luke 23:56).

Christian monarchy

While the Byzantine emperors from Justinian I onward considered themselves anointed by God—and specifically not by the Roman pope—in Christian Europe, the Merovingian monarchy was the first known to anoint the king in a coronation ceremony that was designed to epitomize the Catholic Church's conferring a religious sanction of the monarch's divine right to rule.

The French Kings adopted the fleur-de-lis as a baptismal symbol of purity on the conversion of the Frankish King Clovis I to the Christian religion in 493. To further enhance its mystique, a legend eventually sprang up that a vial of oil descended from Heaven to anoint and sanctify Clovis as King. The "anointed" kings of France later maintained, as did their Byzantine counterparts, that their authority was directly from God, without the mediation of either the Emperor or the Pope. In the Byzantine Empire, the ecclesiastical rite of anointing by the patriarch of Constantinople was incorporated in the twelfth century.

English monarchs also included anointing in the coronation rituals. The Sovereign of the United Kingdom is the last anointed monarch. For the coronation of King Charles I in 1626 the holy oil was made of a concoction of orange, jasmine, distilled roses, distilled cinnamon, oil of ben, extract of bensoint, ambergris, musk, and civet.

Since anointing no longer symbolizes the king's subordination to the religious authority, even in Catholic countries, it is not performed by the pope but usually reserved for the (arch)bishop of a major see. Hence the utensils of anointing can be part of the regalia.

Christian sacramental usage

In early Christian times, sick people were anointed for healing to take place :"Is any sick among you? let him call for the elders of the church; and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord." (:James 5:14-15)

In Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox usage, anointing is part of the sacrament of Anointing of the Sick (or, using the Orthodox terminology, the Mystery of Unction). The Orthodox use unction not only for physical ailments, but for spiritual ailments as well, and the faithful may re request unction at will. It is normal for everyone to receive unction during Holy Week.

Consecrated oil is also used in confirmation. The Eastern Churches perform the sacrament of Chrismation immediately after the sacrament of Baptism, during the same ceremony.

Pentecostal churches

Anointing with oil is used in Pentecostal churches for healing the sick and also for consecration or ordination of pastors and elders.

The word "anointing" is also frequently used by Pentecostal Christians to refer to the power of God or the Spirit of God residing in a Christian: a usage that occurs from time to time in the Bible (e.g. in 1 John 2:20). A popular expression is "the anointing that breaks the yoke," which is derived from Isaiah 10:27: "And it shall come to pass on that day, that his burden shall be removed from upon your shoulder, and his yoke from upon your neck, and the yoke shall be destroyed because of oil."

See Also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Austin, Gerard. Anointing with the Spirit: The Rite of Confirmation: The Use of Oil and Chrism. New York: Pueblo Publication Co., 1985. ISBN 978-0916134709

- Florenza, Francis S., and Galvin, John P. Systematic Theology: Roman Catholic Perspectives. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0800624613

- Henry, Melanie, and Lynnes, Gina. Anointing for Protection. New Kensington, PA: Whitaker House, 2002. ISBN 978-0883686898

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.