Alan Turing

| Alan Turing |

|---|

| Born |

| June 23, 1912 London, England |

| Died |

| June 7, 1954 |

Alan Mathison Turing, OBE (June 23, 1912 – June 7, 1954), was an English mathematician, logician, and cryptographer.

Turing is often considered to be the father of modern computer science. Turing provided an influential formalisation of the concept of the algorithm and computation with the Turing machine, formulating the now widely accepted "Turing" version of the Church–Turing thesis, namely that any practical computing model has either the equivalent or a subset of the capabilities of a Turing machine. With the Turing test, he made a significant and characteristically provocative contribution to the debate regarding artificial intelligence: whether it will ever be possible to say that a machine is conscious and can think. He later worked at the National Physical Laboratory, creating one of the first designs for a stored-program computer, although it was never actually built. In 1947 he moved to the University of Manchester to work, largely on software, on the Manchester Mark I, then emerging as one of the world's earliest true computers.

During the Second World War, Turing worked at Bletchley Park, Britain's codebreaking centre, and was for a time head of Hut 8, the section responsible for German naval cryptanalysis. He devised a number of techniques for breaking German ciphers, including the method of the bombe, an electromechanical machine that could find settings for the Enigma machine.

In 1952, Turing was convicted of "acts of gross indecency" after admitting to a sexual relationship with a man in Manchester. He was placed on probation and required to undergo hormone therapy. Turing died after eating an apple laced with cyanide in 1954. His death was ruled as suicide.

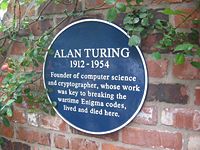

Childhood and youth

Turing was conceived in 1911 in Chatrapur, India. His father, Julius Mathison Turing, was a member of the Indian civil service. Julius and wife Sara (née Stoney) wanted Alan to be brought up in England, so they returned to Maida Vale[1], London, where Alan Turing was born June 23, 1912, as recorded by a blue plaque on the outside of the building, now the Colonnade Hotel.[2][3] His father's civil service commission was still active, and during Turing's childhood years his parents travelled between Guildford, England and India, leaving their two sons to stay with friends in England, rather than risk their health in the British colony. Very early in life, Turing showed signs of the genius he was to display more prominently later. He is said to have taught himself to read in three weeks, and to have shown an early affinity for numbers and puzzles.

His parents enrolled him at St Michael's, a day school, at the age of six. The headmistress recognised his genius early on, as did many of his subsequent educators. In 1926, at the age of 14, he went on to Sherborne School in Dorset. His first day of term coincided with a general strike in England, and so determined was he to attend his first day that he rode his bike unaccompanied more than 60 miles from Southampton to school, stopping overnight at an inn — a feat reported in the local press.

Turing's natural inclination toward mathematics and science did not earn him respect with the teachers at Sherborne, a famous and expensive public school, whose definition of education placed more emphasis on the classics. His headmaster wrote to his parents: "I hope he will not fall between two schools. If he is to stay at public school, he must aim at becoming educated. If he is to be solely a Scientific Specialist, he is wasting his time at a public school".[4]

Despite this, Turing continued to show remarkable ability in the studies he loved, solving advanced problems in 1927 without having even studied elementary calculus. In 1928, aged 16, Turing encountered Albert Einstein's work; not only did he grasp it, but he extrapolated Einstein's questioning of Newton's laws of motion from a text in which this was never made explicit.

Turing's hopes and ambitions at school were raised by his strong feelings for his friend Christopher Morcom, with whom he fell in love, though the feeling was not reciprocated. Morcom died suddenly only a few weeks into their last term at Sherborne, from complications of bovine tuberculosis, contracted after drinking infected cow's milk as a boy.

University and his work on computability

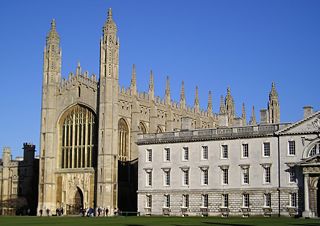

Turing's unwillingness to work as hard on his classical studies as on science and mathematics meant he failed to win a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, and went on to the college of his second choice, King's College, Cambridge. He was an undergraduate from 1931 to 1934, graduating with a distinguished degree, and in 1935 was elected a fellow at King's on the strength of a dissertation on the Gaussian error function.

In his momentous paper "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem" (submitted on May 28, 1936), Turing reformulated Kurt Gödel's 1931 results on the limits of proof and computation, substituting Gödel's universal arithmetic-based formal language by what are now called Turing machines, formal and simple devices. He proved that such a machine would be capable of performing any conceivable mathematical problem if it were representable as an algorithm, even if no actual Turing machine would be likely to have practical applications, being much slower than alternatives.

Turing machines are to this day the central object of study in theory of computation. He went on to prove that there was no solution to the Entscheidungsproblem by first showing that the halting problem for Turing machines is undecidable: it is not possible to decide algorithmically whether a given Turing machine will ever halt. While his proof was published subsequent to Alonzo Church's equivalent proof in respect to his lambda calculus, Turing's work is considerably more accessible and intuitive. It was also novel in its notion of a "Universal (Turing) Machine", the idea that such a machine could perform the tasks of any other machine. The paper also introduces the notion of definable numbers.

Most of 1937 and 1938 he spent at Princeton University, studying under Alonzo Church. In 1938 he obtained his Ph.D. from Princeton; his dissertation introduced the notion of relative computing where Turing machines are augmented with so-called oracles, allowing a study of problems that cannot be solved by a Turing machine.

Back in Cambridge in 1939, he attended lectures by Ludwig Wittgenstein about the foundations of mathematics.[5] The two argued and disagreed, with Turing defending formalism and Wittgenstein arguing that mathematics is overvalued and does not discover any absolute truths.[6]

Cryptanalysis

During the Second World War, Turing was a main participant in the efforts at Bletchley Park to break German ciphers. Building on cryptanalysis work carried out in Poland before the war, he contributed several insights into breaking both the Enigma machine and the Lorenz SZ 40/42 (a teletype cipher attachment codenamed "Tunny" by the British), and was, for a time, head of Hut 8, the section responsible for reading German naval signals.

Since September 1938, Turing had been working part-time for the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS), the British codebreaking organisation. He worked on the problem of the German Enigma machine, and collaborated with Dilly Knox, a senior GCCS codebreaker.[7] On 4 September 1939, the day after Britain declared war on Germany, Turing reported to Bletchley Park, the wartime station of GCCS.[8]

The Turing-Welchman bombe

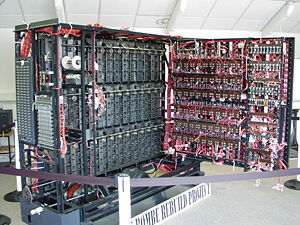

Within weeks of arriving at Bletchley Park,[8] Turing had devised an electromechanical machine which could help break Enigma: the bombe, named after the Polish-designed bomba. The bombe, with an enhancement suggested by mathematician Gordon Welchman, became the primary tool used to read Enigma traffic.

The bombe searched for the correct settings of the Enigma rotors, and required a suitable "crib": a piece of matching plaintext and ciphertext. For each possible setting of the rotors, the bombe performed a chain of logical deductions based on the crib, implemented electrically. The bombe detected when a contradiction had occurred, and ruled out that setting, moving onto the next. Most of the possible settings would cause contradictions and be discarded, leaving only a few to be investigated in detail. Turing's bombe was first installed on 18 March 1940.[9] Over 200 bombes were in operation by the end of the war.[citation needed]

In December 1940, Turing solved the naval Enigma indicator system, which was more complex than the indicator systems used by the other services. Turing also invented a Bayesian statistical technique termed "Banburismus" to assist in breaking Naval Enigma. Banburismus could rule out certain orders of the Enigma rotors, reducing time needed to test settings on the bombes.

In the spring of 1941, Turing proposed marriage to Hut 8 co-worker Joan Clarke, although the engagement was broken off by mutual agreement in the summer.

In July 1942, Turing devised a technique termed Turingismus or Turingery for use against the "Fish" Lorenz cipher. He also introduced the Fish team to Tommy Flowers, who went on to design the Colossus computer.[10] A frequent misconception is that Turing was a key figure in the design of Colossus; this was not the case.[11]

Turing travelled to the United States in November 1942 and worked with US Navy cryptanalysts on Naval Enigma and bombe construction in Washington, and assisted at Bell Labs with the development of secure speech devices. He returned to Bletchley Park in March 1943. During his absence, Hugh Alexander had officially assumed the position of head of Hut 8, although Alexander had been de facto head for some time, Turing having little interest in the day-to-day running of the section. Turing became a general consultant for cryptanalysis at Bletchley Park.

In the latter part of the war, teaching himself electronics at the same time, Turing undertook (assisted by engineer Donald Bayley) the design of a portable machine codenamed Delilah to allow secure voice communications. Intended for different applications, Delilah lacked capability for use with long-distance radio transmissions, and was completed too late to be used in the war. Though Turing demonstrated it to officials by encrypting/decrypting a recording of a Winston Churchill speech, Delilah was not adopted for use.

In 1945, Turing was awarded the OBE for his wartime services, but his work remained secret for many years. A biography published by the Royal Society shortly after his death recorded:

- "Three remarkable papers written just before the war, on three diverse mathematical subjects, show the quality of the work that might have been produced if he had settled down to work on some big problem at that critical time. For his work at the Foreign Office he was awarded the OBE."[12]

Early computers and the Turing Test

From 1945 to 1947 he was at the National Physical Laboratory, where he worked on the design of the ACE (Automatic Computing Engine). He presented a paper on February 19, 1946, which was the first complete design of a stored-program computer in Britain. Although he succeeded in designing the ACE, there were delays in starting the project and he became disillusioned. In late 1947 he returned to Cambridge for a sabbatical year. While he was at Cambridge, ACE was completed in his absence and executed its first program on May 10, 1950. In 1949 he became deputy director of the computing laboratory at the University of Manchester, and worked on software for one of the earliest true computers — the Manchester Mark I. During this time he continued to do more abstract work, and in "Computing machinery and intelligence" (Mind, October 1950), Turing addressed the problem of artificial intelligence, and proposed an experiment now known as the Turing test, an attempt to define a standard for a machine to be called "sentient".

In 1948, Turing, working with his former undergraduate colleague, D.G. Champernowne, began writing a chess program for a computer that did not yet exist. In 1952, lacking a computer powerful enough to execute the program, Turing played a game in which he simulated the computer, taking about half an hour per move. The game was recorded; the program lost to Turing's colleague Alick Glennie, although it is said that it won a game against Champernowne's wife.

Pattern formation and mathematical biology

Turing worked from 1952 until his death in 1954 on mathematical biology, specifically morphogenesis. He published one paper on the subject called "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis" in 1952, putting forth the Turing hypothesis of pattern formation.[1] His central interest in the field was understanding Fibonacci phyllotaxis, the existence of Fibonacci numbers in plant structures. He used reaction-diffusion equations which are now central to the field of pattern formation. Later papers went unpublished until 1992 when Collected Works of A.M. Turing was published.

Prosecution for homosexual acts and Turing's death

Turing was a homosexual during a period when homosexual acts were illegal in England and homosexuality was regarded as a mental illness. In 1952, Arnold Murray, a 19-year-old recent acquaintance of his[16] helped an accomplice to break into Turing's house, and Turing went to the police to report the crime. As a result of the police investigation, Turing acknowledged a sexual relationship with Murray, and they were charged with gross indecency under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885. Turing was unrepentant and was convicted. He was given the choice between imprisonment and probation, conditional on him undergoing hormonal treatment designed to reduce libido. In order to avoid going to jail, he accepted the oestrogen hormone injections, which lasted for a year, with side effects including the development of breasts. His conviction led to a removal of his security clearance and prevented him from continuing consultancy for GCHQ on cryptographic matters.

In 1954, he died of cyanide poisoning, apparently from a cyanide-laced apple he left half-eaten. The apple itself was never tested for contamination with cyanide, and cyanide poisoning as a cause of death was established by a post-mortem. Most believe that his death was intentional, and the death was ruled a suicide. His mother, however, strenuously argued that the ingestion was accidental due to his careless storage of laboratory chemicals. Biographer Andrew Hodges suggests that Turing may have killed himself in this ambiguous way quite deliberately, to give his mother some plausible deniability.[17] The possibility of assassination has also been suggested:[18] Turing's homosexuality would then have been perceived as a security risk.

Posthumous recognition

Since 1966, the Turing Award has been given annually by the Association for Computing Machinery to a person for technical contributions to the computing community. It is widely considered to be the computing world's equivalent to the Nobel Prize.

Various tributes to Turing have been made in Manchester, the city where he worked towards the end of his life. In 1994 a stretch of the Manchester city inner ring road was named Alan Turing Way.

A statue of Turing was unveiled in Manchester on June 23 2001. It is in Sackville Park, between the University of Manchester building on Whitworth Street and the Canal Street 'gay village'. A celebration of Turing's life and achievements arranged by the British Logic Colloquium and the British Society for the History of Mathematics was held on 5 June 2004 at the University of Manchester and the Alan Turing Institute was initiated in the university that summer.

On 23 June 1998, on what would have been Turing's 86th birthday, Andrew Hodges, his biographer, unveiled an official English Heritage Blue Plaque on his childhood home in Warrington Crescent, London, now the Colonnade hotel.[19][20] To mark the 50th anniversary of his death, a memorial plaque was unveiled on June 7 2004 at his former residence, Hollymeade, in Wilmslow.

For his achievements in computing, various universities have honoured him. On October 28 2004 a bronze statue of Alan Turing sculpted by John W. Mills was unveiled at the University of Surrey [2]. The statue marks the 50th anniversary of Turing's death. It portrays Turing carrying his books across the campus. The Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico and Los Andes University of Bogotá, Colombia, both have computer laboratories named after Turing. The University of Texas at Austin has an honours computer science program named the Turing Scholars. Istanbul Bilgi University organizes an annual conference on the theory of computation called Turing Days. Carnegie Mellon University has a granite bench, situated in The Hornbostel Mall, with the name "Alan Turing" carved across the top, "Read" down the left leg, and "Write" down the other.

The Boston GLBT pride organization named Turing their 2006 Honorary Grand Marshal.

Turing biographies

- Turing's mother, Sara Turing, who survived him by many years, wrote a biography of her son glorifying his life. Published in 1959, it could not cover his war work; scarcely 300 copies were sold.[21] Its six-page foreword, by Lyn Irvine, includes reminiscences and is more frequently quoted.

- Andrew Hodges wrote a definitive biography Alan Turing: The Enigma in 1983 (see references below).

- The play Breaking the Code by Hugh Whitemore is about the life and death of Turing. In the original West End and Broadway runs, the role of Turing was played by Derek Jacobi, who also played Turing in a 1996 television adaptation of the play.

- Turing is examined in A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines by Janna Levin.

- Leavitt, David (2005). The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-05236-2.

- Code-Breaker, by Jim Holt is reviewed by the New Yorker here: http://www.newyorker.com/critics/books/?060206crbo_books

Further reading

- Bodanis, David. Electric Universe: How Electricity Switched on the Modern World. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2005. ISBN 0-307-33598-4

Turing in fiction

- Physicist Janna Levin's novel A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines focuses on the lives of both Alan Turing and Kurt Gödel.

- Turing appears as a character in Neal Stephenson's Cryptonomicon.

- A young Alan Turing introduces the title character to Gödel's first incompleteness theorem in Apostolos Doxiadis's novel Uncle Petros and Goldbach's Conjecture.

- In the 1989 Doctor Who serial The Curse of Fenric, the character of Dr Judson is based on Turing. Turing himself is a narrator of the Doctor Who spin-off novel The Turing Test by Paul Leonard.

- Greg Egan's novella, Oracle, is about an alternate universe version of Turing

- In John Banville's The Untouchable, the character Alastair Sykes is modeled on Alan Turing.

- In William Gibson's seminal cyberpunk novel Neuromancer, the sinister body tasked with the regulation and suppression of artificial intelligences is called the "Turing Registry", and its agents are referred to as the "Turing Police".

- In 1987 German author and playwright Rolf Hochhuth published the novel Alan Turing after reading the biography written by Turing's mother.

- The 2007 Charlie Higson children's novel "Double or Die" features Turing as a minor character.

See also

- List of gay, lesbian or bisexual people

- Alan Turing's Unorganized Machines

- Philosophy of information

- Good-Turing frequency estimation

Footnotes

- ↑ "English heritage Blue Plaques- Alan Turing"

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 5

- ↑ The Alan Turing Internet Scrapbook. Retrieved 2006-09-26.

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 26

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 152

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 153-154

- ↑ Jack Copeland, "Colossus and the Dawning of the Computer Age", p. 352 in Action This Day, 2001

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Copeland, 2006, p. 378

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 191

- ↑ Copeland, 2006, pp. 72

- ↑ Copeland, 2006, pp. 382-383

- ↑ Newman, 1955, p254

- ↑ Lucy Sherriff, "Turing honoured with bronze statue"., The Register (October 29 2004)

- ↑ "Alan Turing Scrapbook".

- ↑ The Times, "Athletics: Marathon and Decathlon Championships", (25 August 1947)

- ↑ cf. Hodges, pp.449-455

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, pp. 488-489

- ↑ Holt, 2006

- ↑ Unveiling the official Blue Plaque on Alan Turing's Birthplace. Retrieved 2006-09-26.

- ↑ About this Plaque - Alan Turing. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- ↑ Sara Turing to Lyn Newman, 1967, Library of St. John's College, Cambridge.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson. Alan Mathison Turing at the MacTutor archive

- B. Jack Copeland, (2004) "Colossus: Its Origins and Originators". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 26(4):38–45.

- B. Jack Copeland, (editor, 2004) The Essential Turing. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-825079-7 (hardback) and ISBN 0-19-825080-0 (paperback).

- B. Jack Copeland, (editor, 2005), Alan Turing's Automatic Computing Engine. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-856593-3.

- B. Jack Copeland (editor, 2006), Colossus: The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers, 2006, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-284055-X.

- Andrew Hodges, (1983/2000). Alan Turing: The Enigma. Simon & Schuster, 1983, ISBN 0-671-49207-1. Also: Walker Publishing Company, 2000.

- M. H. A. Newman, Alan Mathison Turing. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 1955, Volume 1. The Royal Society 1955.

- Christof Teuscher (editor 2004), Alan Turing: Life and Legacy of a Great Thinker. Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-20020-7.

- David M. Yates, (1997) Turing's Legacy: A history of computing at the National Physical Laboratory 1945–1995. London: Science Museum, ISBN 0-901805-94-7.

- Ludwig Wittgenstein (1932/1976) Wittgenstein's Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics (1932–1935). Edited by Cora Diamond. Cornell University Press.

- Johnson, George (2005) "Enigmatic". New York Times Book Review (12/18/2005). Review of David Leavitt, The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer (2005).

- Holt, Jim (2006) "CODE-BREAKER The life and death of Alan Turing.". The New Yorker (1/30/2006). Review of David Leavitt, The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer (2005).

External links

- Alan Turing site maintained by Andrew Hodges including a short biography

- AlanTuring.net Turing Archive for the History of Computing by Jack Copeland

- The Turing Archive - contains scans of some unpublished documents and material from the Kings College archive

- Alan Turing – Towards a Digital Mind: Part 1

- Time 100:Alan Turing

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Hollymeade unveiling of memorial plaque marking 50th anniversary of Turing's untimely death

- Alan Turing and morphogenesis

- Photos

- More photos

- Morton, Paul Econoculture Interview with David Leavitt about The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer February 2 2006

Papers

- "Computing machinery and intelligence"

- Turing's paper titled "On Computable Numbers with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem" (PDF)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.