Difference between revisions of "Gershom Scholem" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''Gerschom Scholem''' (December 5, 1897 – February 21, 1982), also known as '''Gerhard Scholem''', was a [[Jew]]ish philosopher and historian widely regarded as the modern founder of the scholarly study of [[Kabbalah]]. Raised in Germany, he rejected his parents assimilationist views, and immigrated to Palestine in 1923. He became a leading figure in Zionist intellectual community of Palestine before WWII, and later became the first Professor of Jewish Mysticism at the [[Hebrew University of Jerusalem]]. Although an ardent Zionist, Scholem remained a secular Jew throughout his life. | + | '''Gerschom Scholem''' (December 5, 1897 – February 21, 1982), also known as '''Gerhard Scholem''', was a [[Jew]]ish philosopher and historian widely regarded as the modern founder of the scholarly study of [[Kabbalah]]. Raised in Germany, he rejected his parents assimilationist views, and immigrated to Palestine in 1923. He became a leading figure in Zionist intellectual community of Palestine before WWII, and later became the first Professor of Jewish Mysticism at the [[Hebrew University of Jerusalem]]. Although a leading student of mysticism and an ardent Zionist, Scholem remained a [[secular Jew]], rather than a religious one, throughout his life. |

Scholem is best known for his collection of lectures, ''Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism'' (1941) and for his biography ''Sabbatai Zevi, the Mystical Messiah'' (1973), as well as several other books on kabbalism. His collected speeches and essays, published as ''On Kabbalah and its Symbolism'' (1965), helped to spread knowledge of Jewish mysticism among Jews and non-Jews alike. He published over 40 volumes and nearly 700 articles. As a teacher, he trained three generations of scholars of Kabbala, many of whom still teach. | Scholem is best known for his collection of lectures, ''Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism'' (1941) and for his biography ''Sabbatai Zevi, the Mystical Messiah'' (1973), as well as several other books on kabbalism. His collected speeches and essays, published as ''On Kabbalah and its Symbolism'' (1965), helped to spread knowledge of Jewish mysticism among Jews and non-Jews alike. He published over 40 volumes and nearly 700 articles. As a teacher, he trained three generations of scholars of Kabbala, many of whom still teach. | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

Scholem was awarded the [[Israel Prize]] in 1958 and was elected president of the [[Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities]] in 1968. | Scholem was awarded the [[Israel Prize]] in 1958 and was elected president of the [[Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities]] in 1968. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Early life== |

| − | Scholem was born in [[Berlin]] to Arthur Scholem and Betty Hirsch Scholem. His interest in Judaica was strongly opposed by his father, a printer with liberal and assimilationist views. Thanks to his mother's intervention, he was allowed to study [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] and the [[Talmud]] with an [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox]] rabbi and soon became interested in the Kabbalah, although he never became personally religious. | + | Scholem was born in [[Berlin]] to Arthur Scholem and Betty Hirsch Scholem. His interest in Judaica was strongly opposed by his father, a successful printer with liberal and assimilationist views. Thanks to his mother's intervention, he was allowed to study [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] and the [[Talmud]] with an [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox]] rabbi and soon became interested in the Kabbalah, although he never became personally religious. |

| − | Banished from home for his Zionist and anti-German nationalist views, he befriended Zalman Shazar, a future president of Israel, and several other Zionists in Berlin, with whom he lived. Scholem studied mathematics, philosophy, and Hebrew at the [[Humboldt University of Berlin|University of Berlin]], where he came into contact with [[Martin Buber]] and [[Walter Benjamin]]. He was in Bern in 1918 with Benjamin when he met Elsa Burckhardt, who became his wife. He returned to Germany in 1919, where he received a degree in [[semitic languages]] at the [[Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich|University of Munich]]. | + | Banished from home for his Zionist and anti-German nationalist views, he befriended [[Zalman Shazar]], a future president of Israel, and several other young Zionists in Berlin, with whom he lived. Scholem als studied mathematics, philosophy, and Hebrew at the [[Humboldt University of Berlin|University of Berlin]], where he came into contact with [[Martin Buber]] and [[Walter Benjamin]]. He was in Bern in 1918 with Benjamin when he met Elsa Burckhardt, who became his first wife. He returned to Germany in 1919, where he received a degree in [[semitic languages]] at the [[Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich|University of Munich]]. |

{{Kabbalah}} | {{Kabbalah}} | ||

| − | Scholem wrote his doctoral thesis on the oldest known kabbalistic text, ''[[Bahir|Sefer ha-Bahir]]''. Influenced by Buber and his other Zionist friends, he emigrated in 1923 to the [[British Mandate of Palestine]], later [[Israel]], where he devoted his time to studying Jewish mysticism. During this time he worked as a librarian and eventually became the head of the Department of Hebrew and Judaica at the newly founded National Library. In this position he was able to collect and organize hundreds of kabbalistic texts, in which few scholars | + | Scholem wrote his doctoral thesis on the oldest known kabbalistic text, ''[[Bahir|Sefer ha-Bahir]]''. Influenced by Buber and his other Zionist friends, he emigrated in 1923 to the [[British Mandate of Palestine]], later [[Israel]], where he devoted his time to studying Jewish mysticism. During this time he worked as a librarian and eventually became the head of the Department of Hebrew and Judaica at the newly founded National Library. In this position he was able to collect and organize hundreds of kabbalistic texts, in which few scholars had any interest at the time. He later became a lecturer in Judaica at the [[Hebrew University of Jerusalem]]. |

| − | Scholem taught the Kabbalah and mysticism from a scientific point of view. He became the first professor of Jewish mysticism at the university in 1933 | + | Scholem taught the Kabbalah and mysticism from a scientific point of view. He became the first professor of Jewish mysticism at the university in 1933. In 1936, he married his second wife, Fania Freud. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Theories and scholarship== | ==Theories and scholarship== | ||

===Early work=== | ===Early work=== | ||

| − | Jewish mysticism was seen as | + | In Jewish academic circles of the early twentieth century, Jewish mysticism was rarely studied and was often seen as an embarrassment. Directed to a prominent rabbi who was an "expert" on Kabbalah, Scholem noticed the rabbi's many books on the subject and asked about them, only to be told: "This trash? Why would I waste my time reading nonsense like this?" (Robinson 2000, p. 396) |

| + | |||

| + | Scholem, however, recognized that kabbalistic studies represented a major and underdeveloped field of study. He thus continued his arduous work of collecting and cataloging manuscripts. His first major publications after his dissertation were all bibliographical works related to this work: ''Bibliographia Kabbalistica'' (1927), ''Kitvei Yad ha-Kabbala'' (1930), and ''Perakim le-Toldot sifrut ha-Kabbala'' (1931). | ||

| − | + | His major work on Sabbateanism was published in its preliminary form as “Redemption though Sin,” published in 1936, with a revised English version appearing in 1971 under the title ''Sabbatei Zevi: Mystical Messiah''. In this work, Scholem taught that there are two kinds of Jeiwsh messianism. The first is restorative, meaning that it seeks the restoration of the Davidic monarchy. The second is apocalytic, of "utopian-catastrophic." These two trends in the Jewish messianic hope first come together in the phenomenon of Sabbateansism. | |

| − | === | + | ===Historiograpy=== |

| − | |||

| − | Scholem | + | In the late 1930's, Scholem gave a series of lectures at the Jewish Institute of Religion in New York, published as ''Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism'' in 1941 and considered by many to be his most influential work. |

| − | Scholem | + | Scholem took a dialectical approach to the understanding of the history of Jewish mysticism. For example he did not see [[Sabbateanism]] as ending failure but—in tension with the conservative [[Talmud]]ism of its time—setting the conditions for the emergence of Jewish modernity. |

| − | + | Scholem directly contrasted his historiographical approach to the study of Jewish [[mysticism]] with the approach of the nineteenth-century school of the ''[[Wissenschaft des Judentums]]'' ("Science of Judaism"). The analysis of Judaism carried out by the ''Wissenschaft'' school was flawed in two ways, according to Scholem: First, it studied Judaism as a dead object rather than as a living organism. Second, it did not consider the proper ''foundations'' of Judaism, the trans-rational force that, in Scholem's view, made the religion a living thing. | |

| − | |||

| − | In Scholem's opinion, the mythical and mystical components of Judaism in general and Kabblah in particular were as important as the rational ones. He also strenuously disagreed with what he considered to be [[Martin Buber]]'s personalization of Kabbalistic concepts, | + | In Scholem's opinion, the mythical and mystical components of Judaism in general, and Kabblah in particular, were as important as the rational ones. He also strenuously disagreed with what he considered to be [[Martin Buber]]'s personalization of Kabbalistic concepts. In of Scholem's view, the research of Jewish mysticism could not be separated from its historical context. |

| − | + | Scholem thought that Jewish history could be divided into three major periods: | |

| − | #During the [[Hebrew Bible|Biblical]] period, [[monotheism]] battles [[mythology | + | #During the [[Hebrew Bible|Biblical]] period, [[monotheism]] battles [[mythology]], without completely defeating it; and thus many irrational and magical elements remain. |

| − | # | + | #In the [[Talmud]]ic period, some of the mythical attitudes were removed in favor of the purer concept of the divine [[transcendence (religion)|transcendence]]. |

| − | #During the medieval period, | + | #During the medieval period, Jewish thinkers such as [[Maimonides]], trying to eliminate the remaining irrational myths, created a more and more impersonal Jewish religious tradition. |

| − | The notion of the three periods led Scholem to put forward some controversial arguments. He held that the major seventeenth century messianic movement led [[Shabbetai Zevi]] was developed from the medieval [[Isaac Luria|Lurianic]] Kabbalah. Conservative Talmudists sought to neutralize | + | ===Controversial claims=== |

| + | The notion of the three periods led Scholem to put forward some controversial arguments. He held that the major seventeenth century messianic movement led [[Shabbetai Zevi]] was developed from the medieval [[Isaac Luria|Lurianic]] Kabbalah. Conservative Talmudists then sought to neutralize Sabatteanism. Scholem believed that [[Hasidic Judaism|Hasidism]] had emerged as a Hegelian synthesis, maintaining certain mystical elements within the bounds of normative [[Judaism]]. This idea outraged many of those who had joined the Hasidic movement, who considered it scandalous that their community should be so associated with the heretical movement of Shabbaetai Zevi. Similarly, Scholem held that [[Reform Judaism]] and Jewish secularism represented a rationalist trend in reaction to the mystical enthusiasm of Hasidim and the conservatism of talmudic Orthodoxy. His implication that the contemporary Judaism of his time could benefit from an infusion of kabbalistic studies was also sometimes seen as offensive. | ||

| − | Scholem also produced the controversial hypothesis that the source of the thirteenth century Kabbalah was a Jewish gnosticism that preceded | + | Scholem also produced the controversial hypothesis that the source of the thirteenth century Kabbalah was a Jewish [[gnosticism]] that preceded Christian gnosticism. This is not to say that Scholem held Kabbalah itself to be ancient. However, he pointed to an earlier Jewish mysticism dating back, for example, to the [[Book of Enoch]]. |

The historiographical approach of Scholem also involved a linguistic theory. In contrast to Buber, Scholem believed in the power of the language to invoke supernatural phenomena. In contrast to [[Walter Benjamin]], he put the Hebrew language in a privileged position with respect to other languages, as the a language with special qualities relating to the expression of mystical ideas. | The historiographical approach of Scholem also involved a linguistic theory. In contrast to Buber, Scholem believed in the power of the language to invoke supernatural phenomena. In contrast to [[Walter Benjamin]], he put the Hebrew language in a privileged position with respect to other languages, as the a language with special qualities relating to the expression of mystical ideas. | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | working in this post until his retirement in 1965, when he became an emeritus professor. | ||

==Controversies== | ==Controversies== | ||

Revision as of 20:45, 20 June 2008

Gerschom Scholem (December 5, 1897 – February 21, 1982), also known as Gerhard Scholem, was a Jewish philosopher and historian widely regarded as the modern founder of the scholarly study of Kabbalah. Raised in Germany, he rejected his parents assimilationist views, and immigrated to Palestine in 1923. He became a leading figure in Zionist intellectual community of Palestine before WWII, and later became the first Professor of Jewish Mysticism at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Although a leading student of mysticism and an ardent Zionist, Scholem remained a secular Jew, rather than a religious one, throughout his life.

Scholem is best known for his collection of lectures, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1941) and for his biography Sabbatai Zevi, the Mystical Messiah (1973), as well as several other books on kabbalism. His collected speeches and essays, published as On Kabbalah and its Symbolism (1965), helped to spread knowledge of Jewish mysticism among Jews and non-Jews alike. He published over 40 volumes and nearly 700 articles. As a teacher, he trained three generations of scholars of Kabbala, many of whom still teach.

Scholem was awarded the Israel Prize in 1958 and was elected president of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities in 1968.

Early life

Scholem was born in Berlin to Arthur Scholem and Betty Hirsch Scholem. His interest in Judaica was strongly opposed by his father, a successful printer with liberal and assimilationist views. Thanks to his mother's intervention, he was allowed to study Hebrew and the Talmud with an Orthodox rabbi and soon became interested in the Kabbalah, although he never became personally religious.

Banished from home for his Zionist and anti-German nationalist views, he befriended Zalman Shazar, a future president of Israel, and several other young Zionists in Berlin, with whom he lived. Scholem als studied mathematics, philosophy, and Hebrew at the University of Berlin, where he came into contact with Martin Buber and Walter Benjamin. He was in Bern in 1918 with Benjamin when he met Elsa Burckhardt, who became his first wife. He returned to Germany in 1919, where he received a degree in semitic languages at the University of Munich.

| Kabbalah |

| Sub-topics |

|---|

| Kabbalah |

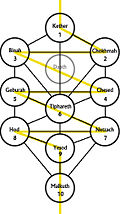

| Sephirot |

| Gematria |

| Qliphoth |

| Raziel |

| Ein Sof |

| Tzimtzum |

| Tree of Life (Kabbalah) |

| Seder hishtalshelus |

| Jewish meditation |

| Kabbalistic astrology |

| Jewish views of astrology |

| People |

| Shimon bar Yohai |

| Moshe Cordovero |

| Isaac the Blind |

| Bahya ben Asher |

| Nachmanides |

| Azriel |

| Arizal |

| Chaim Vital |

| Yosef Karo |

| Israel Sarug |

| Jacob Emden |

| Jacob Emden |

| Jonathan Eybeschutz |

| Chaim ibn Attar |

| Nathan Adler |

| Vilna Gaon |

| Chaim Joseph David Azulai |

| Shlomo Eliyashiv |

| Baba Sali |

| Ben Ish Hai |

| Texts |

| Zohar |

| Sefer Yetzirah |

| Bahir |

| Heichalot |

| Categories |

| Kabbalah |

| Jewish mysticism |

| Occult |

Scholem wrote his doctoral thesis on the oldest known kabbalistic text, Sefer ha-Bahir. Influenced by Buber and his other Zionist friends, he emigrated in 1923 to the British Mandate of Palestine, later Israel, where he devoted his time to studying Jewish mysticism. During this time he worked as a librarian and eventually became the head of the Department of Hebrew and Judaica at the newly founded National Library. In this position he was able to collect and organize hundreds of kabbalistic texts, in which few scholars had any interest at the time. He later became a lecturer in Judaica at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Scholem taught the Kabbalah and mysticism from a scientific point of view. He became the first professor of Jewish mysticism at the university in 1933. In 1936, he married his second wife, Fania Freud.

Theories and scholarship

Early work

In Jewish academic circles of the early twentieth century, Jewish mysticism was rarely studied and was often seen as an embarrassment. Directed to a prominent rabbi who was an "expert" on Kabbalah, Scholem noticed the rabbi's many books on the subject and asked about them, only to be told: "This trash? Why would I waste my time reading nonsense like this?" (Robinson 2000, p. 396)

Scholem, however, recognized that kabbalistic studies represented a major and underdeveloped field of study. He thus continued his arduous work of collecting and cataloging manuscripts. His first major publications after his dissertation were all bibliographical works related to this work: Bibliographia Kabbalistica (1927), Kitvei Yad ha-Kabbala (1930), and Perakim le-Toldot sifrut ha-Kabbala (1931).

His major work on Sabbateanism was published in its preliminary form as “Redemption though Sin,” published in 1936, with a revised English version appearing in 1971 under the title Sabbatei Zevi: Mystical Messiah. In this work, Scholem taught that there are two kinds of Jeiwsh messianism. The first is restorative, meaning that it seeks the restoration of the Davidic monarchy. The second is apocalytic, of "utopian-catastrophic." These two trends in the Jewish messianic hope first come together in the phenomenon of Sabbateansism.

Historiograpy

In the late 1930's, Scholem gave a series of lectures at the Jewish Institute of Religion in New York, published as Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism in 1941 and considered by many to be his most influential work.

Scholem took a dialectical approach to the understanding of the history of Jewish mysticism. For example he did not see Sabbateanism as ending failure but—in tension with the conservative Talmudism of its time—setting the conditions for the emergence of Jewish modernity.

Scholem directly contrasted his historiographical approach to the study of Jewish mysticism with the approach of the nineteenth-century school of the Wissenschaft des Judentums ("Science of Judaism"). The analysis of Judaism carried out by the Wissenschaft school was flawed in two ways, according to Scholem: First, it studied Judaism as a dead object rather than as a living organism. Second, it did not consider the proper foundations of Judaism, the trans-rational force that, in Scholem's view, made the religion a living thing.

In Scholem's opinion, the mythical and mystical components of Judaism in general, and Kabblah in particular, were as important as the rational ones. He also strenuously disagreed with what he considered to be Martin Buber's personalization of Kabbalistic concepts. In of Scholem's view, the research of Jewish mysticism could not be separated from its historical context.

Scholem thought that Jewish history could be divided into three major periods:

- During the Biblical period, monotheism battles mythology, without completely defeating it; and thus many irrational and magical elements remain.

- In the Talmudic period, some of the mythical attitudes were removed in favor of the purer concept of the divine transcendence.

- During the medieval period, Jewish thinkers such as Maimonides, trying to eliminate the remaining irrational myths, created a more and more impersonal Jewish religious tradition.

Controversial claims

The notion of the three periods led Scholem to put forward some controversial arguments. He held that the major seventeenth century messianic movement led Shabbetai Zevi was developed from the medieval Lurianic Kabbalah. Conservative Talmudists then sought to neutralize Sabatteanism. Scholem believed that Hasidism had emerged as a Hegelian synthesis, maintaining certain mystical elements within the bounds of normative Judaism. This idea outraged many of those who had joined the Hasidic movement, who considered it scandalous that their community should be so associated with the heretical movement of Shabbaetai Zevi. Similarly, Scholem held that Reform Judaism and Jewish secularism represented a rationalist trend in reaction to the mystical enthusiasm of Hasidim and the conservatism of talmudic Orthodoxy. His implication that the contemporary Judaism of his time could benefit from an infusion of kabbalistic studies was also sometimes seen as offensive.

Scholem also produced the controversial hypothesis that the source of the thirteenth century Kabbalah was a Jewish gnosticism that preceded Christian gnosticism. This is not to say that Scholem held Kabbalah itself to be ancient. However, he pointed to an earlier Jewish mysticism dating back, for example, to the Book of Enoch.

The historiographical approach of Scholem also involved a linguistic theory. In contrast to Buber, Scholem believed in the power of the language to invoke supernatural phenomena. In contrast to Walter Benjamin, he put the Hebrew language in a privileged position with respect to other languages, as the a language with special qualities relating to the expression of mystical ideas.

working in this post until his retirement in 1965, when he became an emeritus professor.

Controversies

Scholem was opposed to the death sentence against Adolf Eichmann. In the aftermath of the trial in Jerusalem, Scholem sharply criticised Hannah Arendt's book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil and decried her lack of "ahavath Yisrael" (solidarity with the Jewish people).

Influence and legacy

Gershom Scholem stands out as the seminar figure in modern and comtemporary kabbalistic studies. Even beyond his theoretical and analytical work, his efforts to compile and catalog kabbalistic manuscripts in the early twentieth century created a major legacy for future scholars in this field. However, as a writer and lecturer, Scholem did much to reinvigorate academic discussion of the Kabbalah among Jews and to popularize this little known subject about Gentiles.

In the year 1933, the Dutch heiress Olga Froebe-Kapteyn initiated an annual Eranos Conference in Switzerland, bringing together scholars of different religious traditions. Scholem attended and presented papers in many of these. Among those attending were Carl Jung, Mircea Eliade, Paul Tillich and many others. His lectures in New York have already been mentioned. And of course, his many books and articles left a lasting contribution. No serious academic student of the Kabbalah denies their debt to Scholem, even when they disagree with is theories. Perhaps even more important, millions of people, Jews and Gentiles alike, who have studied or dabbled in the Kabbalah as a guide to personal mystical experience probably could not have done so without Scholem's work, even if they are unaware of it.

Scholem was awarded the Israel Prize in 1958 and was elected president of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities in 1968.Throughout his career Scholem also played the important role in the intellectual life of Israel. He often wrote in Israeli publication and gave frequent interviews on many public issues. He remained an emeritus professor an the Hebrew University of Jerusalem until his death in 1982.

Selected works in English

- Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism 1941

- Jewish Gnosticism, Merkabah Mysticism, and the Talmudic Tradition 1960

- From Berlin to Jerusalem: Memories of My Youth. Trans. Harry Zohn, 1980.

Hannah Arendt und Gershom Scholem, Eichmann in Jerusalem: Exchange of Letters between Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt. In: Encounter 22/1 (1964)

- The Messianic Idea in Judaism and other Essays on Jewish Spirituality translated 1971

- Sabbatai Zevi, the Mystical Messiah 1973

- Kabbalah, Meridian 1974, Plume Books 1987 reissue: ISBN 0-452-01007-1

- Walter Benjamin: the Story of a Friendship. Translated from German by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1981.

- Origins of the Kabbalah, JPS, 1987 reissue: ISBN 0-691-02047-7

- On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead : Basic Concepts in the Kabbalah 1997

- The Fullness of Time: Poems (translated by Richard Sieburth)

- On Jews and Judaism in Crisis: Selected Essays

- On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism

- "Tselem: The Representation of the Astral Body" translated by Scott J. Thompson (1987)http://www.wbenjamin.org/scholem.html

- Zohar - The Book of Splendor: Basic Readings from the Kabbalah (Ed.)

| Kabbalah Portal |

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Biography at the Jewish Virtual Library

- Biography

- An analysis of Scholem's lifework from Commentary

- Biographical page

- Robinson, G. Essential Judaism, Pocket Books, 2000.

Further reading

- Biale, David. Gershom Scholem: Kabbalah and Counter-History, second ed., 1982.

- Bloom, Harold, ed. Gershom Scholem, 1987.

- Campanini, Saverio, A Case for Sainte-Beuve. Some Remarks on Gershom Scholem's Autobiography, in P. Schäfer - R. Elior (edd.), Creation and Re-Creation in Jewish Thought. Festschrift in Honor of Joseph Dan on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday, Tübingen 2005, pp. 363-400.

- Campanini, Saverio, Some Notes on Gershom Scholem and Christian Kabbalah, in J. Dan (ed.), Gershom Scholem in Memoriam, Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought, 21 (2007), pp. 13-33.

- Jacobson, Eric, Metaphysics of the Profane - The Political Theology of Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem, (Columbia University Press, NY, 2003).

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.