Difference between revisions of "Mount Hood" - New World Encyclopedia

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) |

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

Prior to the 1980 eruption of [[Mount Saint Helens]], the only known fatality related to [[volcano|volcanic]] activity in the Cascades occurred in 1934 when a climber suffocated in oxygen-poor air while exploring ice caves melted by fumaroles in the Coalman Glacier. These vents near the summit are known for emitting noxious gases such as [[carbon dioxide]] and [[sulfur dioxide]]. | Prior to the 1980 eruption of [[Mount Saint Helens]], the only known fatality related to [[volcano|volcanic]] activity in the Cascades occurred in 1934 when a climber suffocated in oxygen-poor air while exploring ice caves melted by fumaroles in the Coalman Glacier. These vents near the summit are known for emitting noxious gases such as [[carbon dioxide]] and [[sulfur dioxide]]. | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Wildlife and Recreation== | ==Wildlife and Recreation== | ||

| − | Mount Hood is home to more than 300 species of fish and wildlife. Deer, elk, | + | Mount Hood is home to more than 300 species of [[fish]] and wildlife. [[Deer]], [[elk]], [[coyote]]s, and black [[bear]] are just a few of the [[animal]]s that make their home on the mountain. Along its [[river]]s, streams, and mountain [[lake]]s, [[fishing]] for Small Mouth bass, Rainbow trout, Chinook [[salmon]] or Steelhead is a popular sport. <ref> Kocis, Susan M., Donald B.K. English, Stanley J. Zarnoch, Ross Arnold, Larry Warren, Catherine Ruka. June 2004. |

| + | [http://www.fs.fed.us/recreation/programs/nvum/reports/year4/R6_F6_mounthood_final.htm#_Toc75065186 National Visitor Use Monitoring Results] ''USDA Forest Service''. Retrieved September 17, 2007 </ref> | ||

| − | Some of the common birds found in the Mount Hood wetlands are | + | Some of the common birds found in the Mount Hood wetlands are [[heron]]s, [[Canadian geese]], and [[Mallard duck]]s. Hummingbirds, Western Meadowlark, Towhees, Northern Flickers, Steller Jays, Pileated Woodpeckers and many species of [[hawk]]s and [[owl]]s (including the spotted owl) are among the birds that build their nests in old snags and [[forest]] groves on Mount Hood. |

The mountain offers recreation year round including skiing, biking, camping, fishing, hiking, and horseback riding. One can also just relax, which is the most popular pass time for visitors to the mountain. | The mountain offers recreation year round including skiing, biking, camping, fishing, hiking, and horseback riding. One can also just relax, which is the most popular pass time for visitors to the mountain. | ||

| − | Hiking on over 1200 miles of maintained trails | + | Hiking on over 1200 miles of maintained trails is the second most popular use of Mount Hood. Along with the evergreen forests, hikers can enjoy many varieties of deciduous [[tree]]s including golden [[cottonwood]]s, crimson vine [[maple]]s, dogwoods, alders, hemlocks and [[cedar]]s nestled at the 1000 foot and up elevation. |

| + | |||

| + | The third most popular activity at Mount Hood is downhill skiing with Timberline lodge being open year round. There are also many natural [[hot spring]]s and other winter sports areas along with birdwatching and picnicking sites that makes Mount Hood one of the most frequented National Forests in the [[United States]]. | ||

| − | + | ==HERE== | |

==Environment== | ==Environment== | ||

| Line 151: | Line 133: | ||

It becomes evident that optimum maintenance of the forest and watersheds on Mount Hood is essential for protecting our natural resourses which provide fresh water, clean air and the aesthetic beauty it now affords. Our vigilance in Hood's care ensures future benefits for generations to come. | It becomes evident that optimum maintenance of the forest and watersheds on Mount Hood is essential for protecting our natural resourses which provide fresh water, clean air and the aesthetic beauty it now affords. Our vigilance in Hood's care ensures future benefits for generations to come. | ||

| + | ==Mount Hood National Forest== | ||

| + | [[Image:Douglas Firs Mount Hood National Forest.jpg|thumb|right|Old-growth [[Douglas Fir]] in the Mount Hood National Forest]] | ||

| + | The '''Mount Hood National Forest''' is located 20 miles (32 km) east of the city of [[Portland, Oregon]], and the northern [[Willamette River]] valley. The Forest extends south from the [[Columbia River Gorge]] across more than {{Convert|60|mi|km|0}} of [[forest]]ed [[mountain]]s, [[lake]]s and [[stream]]s to the [[Olallie Scenic Area]], a high lake basin under the slopes of [[Mount Jefferson]]. The Forest encompasses some {{Convert|1067043|acre|sqkm|0}}.<ref name="usfs">{{cite web|url=http://www.fs.fed.us/r6/mthood/about/|title=About Us|work=Mt. Hood National Forest|publisher=U.S. Forest Service|lastaccess=2007-09-06}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Visitors to the Forest can enjoy [[fishing]], [[camping]], [[boating]] and [[hiking]] in the summer, [[hunting]] in the fall, and [[skiing]] and other snow sports in the winter. [[Berry]]-picking and [[mushroom]] collection are popular, and for many area residents, a trip in December to cut the family's [[Christmas tree]] is a long-standing tradition.<ref name="usfs"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Forest started as the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, which was established in [[1893]]. It was then divided into several National Forests in 1908, when the northern portion was merged with the [[Bull Run Watershed|Bull Run Reserve]] (city watershed) and named [[Oregon National Forest]]. The name was changed again to Mount Hood National Forest in [[1924]].<ref name="usfs"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Popular destinations in the Forest include<ref name="usfs"/> | ||

| + | *[[Timberline Lodge]], built in [[1937]] high on [[Mount Hood]] | ||

| + | *[[Lost Lake]] | ||

| + | *[[Burnt Lake]] | ||

| + | *[[Trillium Lake]] | ||

| + | *[[Timothy Lake]] | ||

| + | *[[Rock Creek Reservoir]] | ||

| + | *the Old [[Oregon Trail]], including [[Barlow Road]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are 189,200 acres (766 km²) of designated wilderness on the Forest. The largest is the [[Mount Hood Wilderness]], which includes the mountain's peak and upper slopes. Others are [[Badger Creek Wilderness|Badger Creek]], [[Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness|Salmon-Huckleberry]], [[Hatfield Wilderness|Hatfield]], and [[Bull of the Woods Wilderness|Bull of the Woods]]. [[Olallie Scenic Area]] is a lightly-roaded lake basin that provides a primitive recreational experience.<ref name="usfs"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Bark (nonprofit)|Bark]], a nonprofit organization dedicated to stopping [[commercial logging]] on [[Mount Hood]], offers free hikes in the Mount Hood National Forest on the second Sunday of every month. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mount Hood National Forest is one of the most-visited National Forests in the U.S. with over four million annual visitors. Less than five percent camp in the forest. The forest contains 170 developed recreation sites.<ref> {{cite web | ||

| + | | url = http://www.oregonlive.com/news/oregonian/index.ssf?/base/news/1190258728155510.xml&coll=7&thispage=2 | ||

| + | | title = Rethinking camping—A Forest Service plan could dramatically change Mount Hood's offerings | ||

| + | | author = Michael Milstein | ||

| + | | publisher = The Oregonian | ||

| + | | work = OregonLive.com | ||

| + | | date = [[September 20]][[2007]] | ||

| + | | accessdate = 2007-10-06 | ||

| + | }} </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Eng media invaders at timberline P1706.jpeg|thumb|right|275px|National media covered the relatively minor 2007 Presidents Day climbing incident probably due to the intense December 2006 tragedy coverage.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Hood.jpg|thumb|left|275px|North side of Mount Hood as seen from the Mount Hood Scenic Byway.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Mt-Hood-Oregon.jpg|thumb|right|275px|Mount Hood seen from the south. Crater Rock, the remnants of a 200-year-old lava dome, is visible just below the summit.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Sources and Further Reading == | == Sources and Further Reading == | ||

| Line 162: | Line 179: | ||

* Poindexter, Joseph. 1998. ''To the summit: fifty mountains that lure, inspire and challenge''. New York, N.Y.: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. ISBN 1579120415 and ISBN 9781579120412 | * Poindexter, Joseph. 1998. ''To the summit: fifty mountains that lure, inspire and challenge''. New York, N.Y.: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. ISBN 1579120415 and ISBN 9781579120412 | ||

* Bargar, Keith E., Terry E. C. Keith, and Melvin H. Beeson. 1993. ''Hydrothermal alteration in the Mount Hood area, Oregon''. U.S. Geological Survey bulletin, 2054. Washington: U.S. G.P.O. | * Bargar, Keith E., Terry E. C. Keith, and Melvin H. Beeson. 1993. ''Hydrothermal alteration in the Mount Hood area, Oregon''. U.S. Geological Survey bulletin, 2054. Washington: U.S. G.P.O. | ||

| − | + | * Harris, Stephen L., and Stephen L. Harris. 1988. ''Fire mountains of the west the Cascade and Mono Lake volcanoes''. Roadside geology series. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Pub. Co. ISBN 9780878422203 | |

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| Line 168: | Line 185: | ||

* [http://americasroof.com/or.html Mount Hood, Oregon]. ''America's Roof''. Retrieved June 15, 2007. | * [http://americasroof.com/or.html Mount Hood, Oregon]. ''America's Roof''. Retrieved June 15, 2007. | ||

* [http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/Volcanoes/Hood/framework.html Mount Hood, Oregon]. ''United States Geological Survey''. Retrieved June 15, 2007. | * [http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/Volcanoes/Hood/framework.html Mount Hood, Oregon]. ''United States Geological Survey''. Retrieved June 15, 2007. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{credit|Mount_Hood_National_Forest|162630284|Mount_Hood|135275398}} | ||

Revision as of 06:30, 22 October 2007

| Mount Hood | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Mount Hood reflected in Trillium Lake | |||

| Elevation | 11,249 feet (3,429 meters) | ||

| Location | Oregon, USA | ||

| Mountain range | Cascade Range | ||

| Prominence | 7,706 ft (2,349 m)[1] | ||

| Geographic coordinates | {{#invoke:Coordinates|coord}}{{#coordinates:45|22|24.65|N|121|41|45.31|W|type:mountain_region:US | name=

}} | |

| Topographic map | USGS Mount Hood South 45121-C6 | ||

| Type | Stratovolcano | ||

| Geologic time scale | < 500,000 years[2] | ||

| Last eruption | 1790s[2] | ||

| First ascent | 1857-07-11 by Henry Pittock, W. Lymen Chittenden, Wilbur Cornell, and the Rev. T.A. Wood[3] | ||

| Easiest Climbing route | Rock and glacier climb | ||

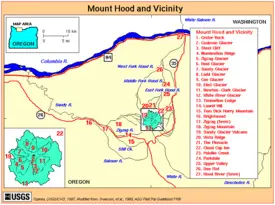

Mount Hood (called Wy'east by the Multnomah tribe), is a stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanoes Arc in northern Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located about 50 miles (80 km) east-southeast of the city of Portland, Oregon, on the border between Clackamas County and Hood River County.

Mount Hood's snow-covered peak rises 11,249 ft (3,429 meters) and is home to twelve glaciers. It is the highest mountain in Oregon and the fourth-highest in the Cascade Range. Mount Hood is considered the most likely of the Oregon volcanos to erupt. Although, based on its history, an explosive eruption is unlikely. Still, the odds of an eruption in the next 30 years are estimated at between 3 and 7 percent. Timberline Lodge is a National Historic Landmark located on the southern flank of Mount Hood just below Palmer Glacier. The mountain has six ski areas: Timberline, Mount Hood Meadows, Ski Bowl, Cooper Spur, Snow Bunny and Summit. They total over 4,600 acres (7.2 mi², 18.6 km²) of ski-able terrain; Timberline offers the only year-round lift-served skiing in North America. Mount Hood is part of the Mount Hood National Forest, which has 1.2 million acres (4,900 km²), four designated wilderness areas, and more than 1,200 mi (1,900 km) of hiking trails.

Origin of name

Mount Hood was given its present name on October 29, 1792 by Lt. William Broughton, a member of Captain George Vancouver's discovery expedition. It was named after a British admiral, Samuel Hood.

The Multnomah tribe's name for Mount Hood is "Wy'east". Legend has it that the name Wy'east comes from a chief of the Multnomah tribe. The chief competed for the attention of a woman who was also loved by the chief of the Klickitat Tribe. The anger that the competition generated led to their transformations into volcanoes, with the Klickitat chief becoming nearby Mount Adams (in neighboring Washington state) and the target of their affection becoming Mount Saint Helens. Their battle was said to have destroyed the Bridge of the Gods, a 200 feet high landslide that crossed the Columbia River approximately 300 years ago, thus creating the Great Cascades of the Columbia River.[4]

Geology

Mount Hood is estimated to be more than 500,000 years old. About 100,000 years ago there was a major eruption that scientists have identified. During this eruption, the north flank collapsed, leveling part of the mountain's peak. As the lahar moved north down the Columbia River in the Hood River Valley area, it carried with it sediment more that 400 ft. deep. The debris left a large crevice that was later filled with lava.

The eroded volcano has had at least four major eruptive periods during the past 15,000 years. The last three occurred within the past 1,800 years. A debris avalanche formed the still visible amphitheater around Crater Rock near the summit approximately 1,500 years ago when vents high on the southwest flank produced deposits. These included boulders 8 feet in diameter, which were distributed primarily to the south and west along the Sandy and Zigzag Rivers. [5]. The last eruptive period took place in 1781-1782. This episode ended shortly before the arrival of Lewis and Clark in 1805. The U.S. Geological Survey characterizes Mt. Hood as "potentially active", while it is sometimes informally described as "dormant".

The glacially eroded summit area consists of several andesitic or dacitic lava domes. These domes formed when slow moving lava flow piled up over the vents. This piling up can eventually cause more dangerous, pyroclastic flows. The "domes" on Hood, sometimes several hundred feet high, can cause Pleistocene collapses, producing avalanches and lahars (rapidly moving mudflows. [6]

Since 1950, there have been several earthquake swarms each year at Mount Hood, generally lasting 2-6 days each occurance. The most notable occurances were in July 1980, and June 2002. [7] Subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate under the North American Plate controls the distribution of these earthquakes and volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest.

Scientists believe that Mount Hood will erupt again. Seismic activity is monitored by the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory located in Vancouver, Washington, which issues daily activity updates. Some of the activites that the geologists watch for as impending threats are increases in temperature near the surface, more seismic activity than usual, and a greater concentration of noxious fumes from the fumaroles. [8].

Glaciers

Mount Hood is host to twelve named glaciers, the most visited of which is Palmer Glacier. This glacier is part of the Timberline Lodge ski area, a popular climbing route. The glaciers are almost exclusively above the 6,000 foot level, which also is about the level of the average tree line on Mount Hood.

The surface area of the glaciers totals approximately 145 million square feet (5.2 square miles) and contains a volume of about 12.3 billion cubic feet (0.084 cubic miles). Eliot Glacier is the largest by volume at 3.2 billion cubic feet, and has the thickest depth measured by ice radar at 361 feet. The largest surface area is the Coe-Ladd Glacier system at 23.1 million square feet. [9]

- Palmer Glacier – upper slopes of the south side, feeds the White River

- Coalman (or "Coleman") Glacier – located between Crater Rock and the summit, drains into White River

- White River Glacier – feeds the White River

- Newton Clark Glacier – source of the East Fork Hood River

- Eliot Glacier – source of Tilly Jane Creek and Eliot Branch, tributaries of Middle Fork Hood River

- Langille Glacier – in Hood River watershed

- Coe Glacier – source of Coe Branch, a tributary of Middle Fork Hood River

- Ladd Glacier –source of McGee Creek, a tributary of West Fork Hood River

- Glisan Glacier

- Sandy Glacier - feeds Muddy Fork, a tributary of the Sandy River

- Reid Glacier – feeds the Sandy River

- Zigzag Glacier – feeds the Zigzag River

Climbing Hazards

There is some debate as to when the summit of Mount Hood was first reached: 1845 or 1857. Since those early days, hundreds of thousands have scaled Oregon's highest peak. Today, it is the most frequently climbed glaciated peak in North America.

There are treacherous conditions involved in the climb with more than 130 people losing their lives in climbing-related accidents since records have been kept on the mountain. [10]

Its status as Oregon's highest point, a prominent landmark visible up to a hundred miles away, convenient access, and relative lack of technical climbing challenges lure many to attempt the climb, which amounts to about 10,000 people per year. On average, one to three lives are lost annually. [11]

Gentle winds and warm air at access points transform into 60°F temperature drops in less than an hour, sudden sustained winds of 60 mph and more, and visibility quickly dropping from hundreds of miles to an arm's length. This pattern is responsible for the most well known incidents of May 1986 and December 2006. One of the worst U.S. climbing accidents occurred in May 1986 when seven students and two faculty of the Oregon Episcopal School froze to death during an annual school climb. The accident in December of 2006 involved three very experienced climbers. Cascade Range weather patterns are unfamiliar to many, even nearby residents. The two major causes of climbing deaths on Mount Hood are falls and hypothermia.

Another reason for the danger in Mt. Hood climbs is the shifting of travel routes. Even experienced climbers can be surprised by unexpected differences from previous experiences on the mountain. One example of this shift was reported in the spring of 2007, relating changes in the formation of the popular South Route. Reportedly, the Hogsback, (part of the South Route), shifted west, increasing the difficulty of the climb. Another change occured when a technical "ice chute" formed in the Pearly Gates, increasing the difficulty of that climb. This change pushed some climbers to choose the "left chute" of the Pearly Gates, however; in this alternative route there is a technical ice wall 30 feet or greater in height, and with fall exposure of over 500 feet. [12]

Prior to the 1980 eruption of Mount Saint Helens, the only known fatality related to volcanic activity in the Cascades occurred in 1934 when a climber suffocated in oxygen-poor air while exploring ice caves melted by fumaroles in the Coalman Glacier. These vents near the summit are known for emitting noxious gases such as carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide.

Wildlife and Recreation

Mount Hood is home to more than 300 species of fish and wildlife. Deer, elk, coyotes, and black bear are just a few of the animals that make their home on the mountain. Along its rivers, streams, and mountain lakes, fishing for Small Mouth bass, Rainbow trout, Chinook salmon or Steelhead is a popular sport. [13]

Some of the common birds found in the Mount Hood wetlands are herons, Canadian geese, and Mallard ducks. Hummingbirds, Western Meadowlark, Towhees, Northern Flickers, Steller Jays, Pileated Woodpeckers and many species of hawks and owls (including the spotted owl) are among the birds that build their nests in old snags and forest groves on Mount Hood.

The mountain offers recreation year round including skiing, biking, camping, fishing, hiking, and horseback riding. One can also just relax, which is the most popular pass time for visitors to the mountain.

Hiking on over 1200 miles of maintained trails is the second most popular use of Mount Hood. Along with the evergreen forests, hikers can enjoy many varieties of deciduous trees including golden cottonwoods, crimson vine maples, dogwoods, alders, hemlocks and cedars nestled at the 1000 foot and up elevation.

The third most popular activity at Mount Hood is downhill skiing with Timberline lodge being open year round. There are also many natural hot springs and other winter sports areas along with birdwatching and picnicking sites that makes Mount Hood one of the most frequented National Forests in the United States.

HERE

Environment

Mount Hood is between the borders of Oregon's Clackamas and Hood River Counties. This scenic region, known as The Hood Territory, includes the following incorporated cities: Canby, Clackamas, Damascus, Estacada, Gladstone, Happy Valley, Lake Oswego, Milwaukie, Molalla, Oregon City, Sandy, West Linn, Wilsonville, and the Villages of Mt. Hood (Government Camp, Welches, Brightwood, Rhododendron and Zigzag).[14]. Mount Hood is part of the 1.2 million acre Mount Hood National Forest. It is managed mainly by the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Department of Interior. Hood Territory is home to two major environmental educational sites, Inkeep Environmental Learning Center located at Clackamas Community College and the Cascade Streamwatch at the Wildwood Recreation Center near Welches, Oregon. The latter site, focuses on watershed and wetland protection and provides a wetland boardwalk interpretive trail for visitors.

The Mt. Hood has deep, well drained soils. Mt. Hood soils are on hillsides in glaciated valleys in mountainous areas and have slopes of 5 to 80 percent. The mean annual precipitation on Hood is about 105 inches and the mean annual air temperature is about 42 degrees F[15]

An organization called Bark, a grassroots network of volunteers dedicated to protecting Oregon's public forests, is calling on the Forest Service to protect the mountain from motor vehicles including OHV's (off highway vehicles). Mount Hood is the first National Forest in the Pacific Northwest to implement the Traveling Plan Rule. This rule designates which roads, trails and areas are open to motorized vehicles. Mount Hood has approximately 4,000 miles of roads. Some of the roads which have not been maintained are causing problems with the watersheds that are a source of drinking water. They are also causing erosion and harm to the wildlife. By monitoring the access of motorized vehicles allowed on Mount Hood, it is believed that less damage will result to the natural habitat on the mountain.[16]

Fires can be beneficial in nature, burning away undergrowth and thinning out overcrowded tree groves. This is helpful because it allows sufficient light and enough space for the trees to grow healthy and fight diseases such as the one caused by the Bark Beetle. [17]. But without proper maintenance fires can be costly and deadly.

In August of 2006, a lighting strike ignited a fire on the East side of Mount Hood beginning what was known as the Hood Complex Fire. When the fire started, thousands of acres of true pine and fir trees in this area where dead or diseased due to the infestation of the Bark Beetle.[18] Their dry, rotten wood contributed to the worst fire season in U.S. history. The magnitude of the Hood Complex fire burned thousands of acres, killed hundreds of animals and fish, required millions of dollars and thousands of manpower hours to control. The smoke made visibility and respiration in the area difficult for more than three weeks.

It becomes evident that optimum maintenance of the forest and watersheds on Mount Hood is essential for protecting our natural resourses which provide fresh water, clean air and the aesthetic beauty it now affords. Our vigilance in Hood's care ensures future benefits for generations to come.

Mount Hood National Forest

The Mount Hood National Forest is located 20 miles (32 km) east of the city of Portland, Oregon, and the northern Willamette River valley. The Forest extends south from the Columbia River Gorge across more than 60 miles (97 km) of forested mountains, lakes and streams to the Olallie Scenic Area, a high lake basin under the slopes of Mount Jefferson. The Forest encompasses some 1,067,043 acres (4,318 km²).[19]

Visitors to the Forest can enjoy fishing, camping, boating and hiking in the summer, hunting in the fall, and skiing and other snow sports in the winter. Berry-picking and mushroom collection are popular, and for many area residents, a trip in December to cut the family's Christmas tree is a long-standing tradition.[19]

The Forest started as the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, which was established in 1893. It was then divided into several National Forests in 1908, when the northern portion was merged with the Bull Run Reserve (city watershed) and named Oregon National Forest. The name was changed again to Mount Hood National Forest in 1924.[19]

Popular destinations in the Forest include[19]

- Timberline Lodge, built in 1937 high on Mount Hood

- Lost Lake

- Burnt Lake

- Trillium Lake

- Timothy Lake

- Rock Creek Reservoir

- the Old Oregon Trail, including Barlow Road

There are 189,200 acres (766 km²) of designated wilderness on the Forest. The largest is the Mount Hood Wilderness, which includes the mountain's peak and upper slopes. Others are Badger Creek, Salmon-Huckleberry, Hatfield, and Bull of the Woods. Olallie Scenic Area is a lightly-roaded lake basin that provides a primitive recreational experience.[19]

Bark, a nonprofit organization dedicated to stopping commercial logging on Mount Hood, offers free hikes in the Mount Hood National Forest on the second Sunday of every month.

Mount Hood National Forest is one of the most-visited National Forests in the U.S. with over four million annual visitors. Less than five percent camp in the forest. The forest contains 170 developed recreation sites.[20]

Notes

- ↑ Mount Hood, Oregon, 11,239 feet, 3426 meters.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mount Hood—History and Hazards of Oregon's Most Recently Active Volcano. U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 060-00. USGS and USFS (June 13,2005). Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ↑ Glaciers of Oregon. Departments of Geology and Geography at Portland State University. Retrieved 2007-02-24. quoting McNeil, Fred H. (1937). Wy'East The Mountain, A Chronicle of Mount Hood. Metropolitan Press. ASIN B000H5CB6E, ASIN B00085VH7W.

- ↑ Clark, Ella Elizabeth. 1953. Indian legends of the Pacific Northwest. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520239261

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey. Mount Hood—History and Hazards of Oregon's Most Recently Active Volcano Retrieved September 14, 2007

- ↑ Scott, W.E., T.C. Pierson, S.P. Schilling, J.E. Costa, C.A. Gardner, J.W. Vallance, and J.J. Major. 1997. Volcano Hazards in the Mount Hood Region, Oregon U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Dept of the Interior Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution. Hood Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey.Cascade Range Current Update Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ↑ Driedger, Carolyn L., and Paul M. Kennard. 1986. Ice volumes on Cascade volcanoes Mount Rainier, Mount Hood, Three Sisters, and Mount Shasta. U.S. Geological Survey professional paper, 1365. Washington: U.S. G.P.O.

- ↑ CBS News. May 31, 2002. Last Body Recovered From Mount Hood Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ Green, Aimee, Mark Larabee and Katy Muldoon. February 19,2007. Everything goes right in Mount Hood search Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ United States Forest Service. May 17, 2007. Mount Hood Climbing Report Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ Kocis, Susan M., Donald B.K. English, Stanley J. Zarnoch, Ross Arnold, Larry Warren, Catherine Ruka. June 2004. National Visitor Use Monitoring Results USDA Forest Service. Retrieved September 17, 2007

- ↑ http://www.mthoodterritory.com/.retreived Sept. 17, 2007

- ↑ .http://ortho.ftw.nrcs.usda.gov/osd/dat/M/MT._HOOD.html

- ↑ http://www.mefeedia.com/feeds/22881/.retreived Sept. 18, 2007

- ↑ http://www.sosforests.com/?cat=15. retrieved Sept. 22, 2007

- ↑ http://www.sosforests.com/?cat=15. retrieved Sept.25,2007

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 About Us. Mt. Hood National Forest. U.S. Forest Service.

- ↑ Michael Milstein (September 202007). Rethinking camping—A Forest Service plan could dramatically change Mount Hood's offerings. OregonLive.com. The Oregonian. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

Sources and Further Reading

- Barstad, Fred. 1998. Hiking Oregon's Mount Hood & Badger Creek Wilderness. A Falcon guide. Helena, Mont: Falcon Pub. ISBN 0585253420 and ISBN 9780585253428

- Fisher, Timothy F. 2006. Surviving Mount Hood. Sault Ste. Marie, Ont: Moose Hide Books. ISBN 1894650522 and ISBN 9781894650526

- Poindexter, Joseph. 1998. To the summit: fifty mountains that lure, inspire and challenge. New York, N.Y.: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. ISBN 1579120415 and ISBN 9781579120412

- Bargar, Keith E., Terry E. C. Keith, and Melvin H. Beeson. 1993. Hydrothermal alteration in the Mount Hood area, Oregon. U.S. Geological Survey bulletin, 2054. Washington: U.S. G.P.O.

- Harris, Stephen L., and Stephen L. Harris. 1988. Fire mountains of the west the Cascade and Mono Lake volcanoes. Roadside geology series. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Pub. Co. ISBN 9780878422203

External links

- Mount Hood, Oregon. Volcano World. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Mount Hood, Oregon. America's Roof. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Mount Hood, Oregon. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.