Venice Film Festival

| |

| Location | Venice, Italy |

|---|---|

| Founded | August 6, 1932 |

| Awards | Golden Lion Silver Lion Volpi Cup and others |

| Artistic director | Alberto Barbera (since 2011) |

| Website | Biennale Cinema |

The Venice Film Festival or Venice International Film Festival (Italian: Mostra Internazionale d'Arte Cinematografica della Biennale di Venezia, "International Exhibition of Cinematographic Art of the Venice Biennale") is an annual film festival held on the island of the Lido in the Venice lagoon, Italy. The festival is held in late August or early September. It is the world's oldest film festival and one of the "Big Five" International film festivals worldwide.

Founded by the National Fascist Party in Venice in August 1932, the festival is part of the Venice Biennale, one of the world's oldest exhibitions of art, created by the Venice City Council on April 19, 1893. The range of work at the Venice Biennale now covers Italian and international art, architecture, dance, music, theatre, and cinema. These works are experienced at separate exhibitions: the International Art Exhibition, the International Festival of Contemporary Music, the International Theatre Festival, the International Architecture Exhibition, the International Festival of Contemporary Dance, the International Kids' Carnival, and the annual Venice Film Festival, which is arguably the best-known of all the events. The purpose of the festival is to promote international cinema as art, entertainment, and as an industry. It is regarded as an Oscars launchpad, hosting the world premieres of Academy Award-winning films.

History

The Venice Film Festival is the world's oldest film festival and one of the "Big Five" worldwide, which include the European Cannes and Berlin festivals, alongside the Toronto International Film Festival in Canada and the Sundance Film Festival in the United States.[1][2] These Festivals are internationally acclaimed for giving creators the artistic freedom to express themselves through film.[3]

The festival is part of the Venice Biennale, one of the world's oldest exhibitions of art, created by the Venice City Council on April 19, 1893.[4] The Biennale has been organized every year since 1895, which makes it the oldest of its kind. The main exhibition held in Castello, in the halls of the Arsenale and Biennale Gardens, alternates every second year between art and architecture (hence the name biennale; biennial). The other events hosted by the Foundation‚ÄĒspanning theatre, music, and dance‚ÄĒare held annually in various parts of Venice, whereas the Venice Film Festival takes place at the Lido.

1930s

During the 1930s, the government and Italian citizens were heavily interested in film. Of the money Italians spent on cultural or sporting events, most of it went for movies.[5] The majority of films screened in Italy were American, which led to government involvement in the film industry and the yearning to celebrate Italian culture in general.[6] With this in mind, the Venice International Film Festival was created by Giuseppe Volpi, Luciano de Feo, and Antonio Maraini in 1932.[7][8][6] Volpi, a statesman, wealthy businessman, and avid fascist who had been Benito Mussolini's minister of finance, was appointed president of the Venice Biennale the same year. Maraini served as the festival's secretary general, and de Feo headed its executive committee.[9]

On the night of August 6, 1932, the festival opened with a screening of the American film Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde on the terrace of the Excelsior Palace Hotel.[10] A total of nine countries participated in the festival, which ended on August 21.[4]

No awards were given at the first festival, but an audience referendum was held to determine which films and performances were most praiseworthy. The French film √Ä Nous la Libert√© was voted the Film Pi√Ļ Divertente (the Funniest Film). The Sin of Madelon Claudet was chosen the Film Pi√Ļ Commovente (the Most Moving Film) and its star, Helen Hayes, the best actress. Most Original Film (Film dalla fantasia pi√Ļ originale) was given to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and its leading man, Fredric March, was voted best actor.

Despite the success of the first festival, it did not return in 1933. In 1934 it returned, and in 1936 the festival was declared to be an annual event.[4] That year the festival also gave its first official awards, namely the Mussolini Cup for Best Italian Film, the Mussolini Cup for Best Foreign Film, and the Corporations Ministry Cup. Seventeen awards were given: fourteen to films and three to individuals. Five films received honorable mentions.

The third installment of the festival in 1935 was headed by its first artistic director, Ottavio Croze, who maintained this position until World War II. The following year, a jury was added to the festival's governing body; it had no foreign members.[8] The majority of funds for the festival came from the Ministry of Popular Culture, with other portions from the Biennale and the city of Venice.[11]

The year 1936 marked another important development in the festival. A law crafted by the Ministry of Popular Culture made the festival an autonomous entity, separate from the main Venice Biennale. This allowed additional fascist organizations, such as the Department of Cinema and the Fascist National Federation of Entertainment Industries, to take control of the festival.[11]

The fifth year of the festival saw the establishment of its permanent home. Designed and completed in 1937, the Palazzo del Cinema was built on the Lido. The Palazzo has since been the site for every Venice Film Festival, with the exception of the three years from 1940 to 1942, when the festival was moved away from Venice for fear of bombing. However, Venice received almost no damage during that time.[7]

1940s

The 1940s represent one of the most difficult moments for the festival itself. Nazi propaganda movie Heimkehr was presented in 1941 winning an award from the Italian Ministry of Popular Culture. With the advent of the conflict the situation degenerated to such a point that the editions of 1940, 1941 and 1942, subsequently are considered as if they did not happen because they were carried out in places far away from Lido.[9] Additionally, the festival was renamed the Italian-German Film Festival (Manifestazione Cinematografica Italo-Germanica) in 1940. The festival carried this title until 1942 when the festival was suspended due to war.[11]

The festival resumed full speed in 1946, after the war. For the first time, the 1946 edition was held in the month of September, in accordance with an agreement with the newly reborn Cannes Film Festival, which had just held its first review in the spring of that year. With the return to normality, Venice once again became a great icon of the film world.[9]

In 1947 the festival was held in the courtyard of the Doge's Palace, a most magnificent backdrop for hosting a record 90 thousand participants. The 1947 festival is widely considered one of the most successful editions in the history of the festival.[9]

Development and closure

In 1951, FIAPF formally accredited the festival.[12]

In 1963 the winds of change blew strongly during Luigi Chiarini‚Äôs directorship of the festival (1963‚Äď1968). During the years of his directorship, Chiarini aspired to renew the spirit and the structures of the festival, pushing for a total reorganization of the entire system. For six years the festival followed a consistent path, according to the rigid criteria put in place for the selection of works in competition, and took a firm stand against the political pressures and interference of more and more demanding movie studios, preferring the artistic quality of films to the growing commercialization of the film industry.

The social and political unrest of 1968 had strong repercussions on the Venice Bienniale. From 1969 to 1979 no prizes were awarded and the festival returned to the non-competitiveness of the first edition due to the Years of Lead. In 1973, 1977 and 1978, the festival was not even held. The Golden Lion didn't make its return until 1980.[9]

Rebirth

The long-awaited rebirth came in 1979, thanks to the new director Carlo Lizzani (1979‚Äď1983), who decided to restore the image and value the festival had lost over the last decade. The 1979 edition laid the foundation for the restoration of international prestige. In an attempt to create a more modern image of the festival, the neo-director created a committee of experts to assist in selecting the works and to increase the diversity of submissions to the festival.

In 2004 an independent and parallel film festival, Giornate degli Autori, was created in association with the festival.

To celebrate the 70th edition of the festival, in 2013 the new section "Venezia 70 ‚Äď Future Reloaded" was created.

During more recent years, under the direction of Alberto Barbera, the festival established itself as an Oscars launchpad,[13] increasing the presence of American movies and hosting the world premieres of Academy Award-winning films such as Gravity (2013), Birdman (2014), Spotlight (2015), La La Land (2016), The Shape of Water (2017), The Favourite (2018), Roma (2018), Joker (2019) and Nomadland (2020).

In 2017 a new section for virtual-reality (VR) films was introduced.

In 2018 Roma by Alfonso Cuarón won the Golden Lion and became the first ever movie produced by Netflix to receive an award in a major film festival.[14]

Festival program

The Venice Film Festival has as its goal "to raise awareness and promote international cinema in all its forms as art, entertainment and as an industry, in a spirit of freedom and dialogue."[15] To accomplish this goal, the Festival is organized into various sections:[16]

- Official Selection - The main event of the festival.

- In Competition - About 21 films competing for the Golden Lion.

- Out of Competition - Maximum of 18 important works of the year will be presented but do not compete for the main prize.

- Orizzonti - The films that represent the latest trends in international cinema by young talents will be presented.

- Venice Classics - Selection of the finest restoration of classic films will be featured.

- Sconfini - Maximum of 10 works that typically includes art house and genre films, experimental works, TV series and cross-media productions will be featured.

- Venice Virtual Reality - Maximum of 30 works in competition and out of competition will be presented.

- Independent and Parallel Sections - These are alternative programmes dedicated to discover other aspects of cinema.

- International Critics' Week - No more than 8 debut films will be screened with its own regulations.

- Giornate degli Autori - No more than 12 films will be promoted by ANAC and 100 Autori Association.

Awards

The Film Festival has four Juries to judge the entries: Venezia 79, Orizzonti, Premio Venezia Opera Prima ‚ÄúLuigi De Laurentiis‚ÄĚ, and Venice Immersive.[15] The awards are:

Official selection: In competition

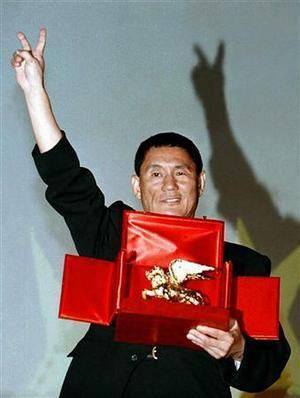

- Golden Lion (Leone d'oro)

The Golden Lion is the highest prize given to a film at the Venice Film Festival.

The prize was introduced in 1949 as the Golden Lion of Saint Mark (which was one of the best known symbols of the ancient Republic of Venice).[17] It is now regarded as one of the film industry's most prestigious and distinguished prizes.[18] Previously, the equivalent prize was the Gran Premio Internazionale di Venezia (Grand International Prize of Venice), awarded in 1947 and 1948. Before that, from 1934 until 1942, the highest awards were the Coppa Mussolini (Mussolini Cup) for Best Italian Film and Best Foreign Film.

No Golden Lions were awarded between 1969 and 1979. This hiatus was a result of the 1968 Lion being awarded to the radically experimental Die Artisten in der Zirkuskuppel: Ratlos: "The Festival still had a statute dating back to the fascist era and could not side-step the general political climate. Sixty-eight produced a dramatic fracture with the past."[19]

Fourteen French films have been awarded the Golden Lion, more than that of any other nation. However, there is considerable geographical diversity in the winners. Eight American filmmakers have won the Golden Lion, with awards for John Cassavetes and Robert Altman (both times the awards were shared with other winners who tied), as well as Ang Lee (Brokeback Mountain was the first winning US film not to tie), Darren Aronofsky, Sofia Coppola, Todd Phillips, Chloé Zhao, and Laura Poitras.

Although prior to 1980, only three of 21 winners were of non-European origin, since the 1980s, the Golden Lion has been presented to a number of Asian filmmakers, particularly in comparison to the Cannes Film Festival's top prize, the Palme d'Or, which has only been awarded to five Asian filmmakers since 1980. The Golden Lion, by contrast, has been awarded to ten Asians during the same time period, with two of these filmmakers winning it twice. Ang Lee won the Golden Lion twice within three years during the 2000s, once for an American film and once for a Chinese-language film. Zhang Yimou has also won twice. Other Asians to win the Golden Lion since 1980 include Jia Zhangke, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tsai Ming-liang, TrŠļßn Anh H√Ļng, Takeshi Kitano, Kim Ki-duk, Jafar Panahi, Mira Nair, and Lav Diaz. Russian filmmakers have also won the Golden Lion several times.

Since 1949, only seven women have won the Golden Lion for directing: Margarethe von Trotta, Agnès Varda, Mira Nair, Sofia Coppola, Chloé Zhao, Audrey Diwan, and Laura Poitras (though it must be noted that in 1938, German director Leni Riefenstahl won the Festival when its highest award was the Coppa Mussolini).

In 2019, Joker became the first movie based on original comic book characters to win the prize.[20]

The Golden Lion Award for Lifetime Achievement in film has been awarded since 1970, when Orson Welles was its first recipient.

- Grand Jury Prize

This prize is awarded to the second best film screened in competition at the festival

- Silver Lion (Leone d'Argento)

The Silver Lion is awarded to the best director in the competitive section

- Special Jury Prize

This is awarded to the third best film screened in competition at the festival

- Volpi Cup (Coppa Volpi) for best actor and actress

The Volpi Cup for Best Actor (Italian: Coppa Volpi per la migliore interpretazione maschile) is the principal award given to actors at the Venice Film Festival and is named in honor of Count Giuseppe Volpi di Misurata, the founder of the Venice Film Festival. The name and number of prizes have been changed several times since their introduction, ranging from two to four awards per edition and sometimes acknowledging both leading and supporting performances.

The Volpi Cup for Best Actress is given by the festival jury in honor of an actress who has delivered an outstanding performance from the films in the competition slate. The first ceremony was held in 1932, when Helen Hayes received the Volpi Cup for the title role in The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931)‚ÄĒthis was the only time that the award was chosen by public voting.

- Golden Osella

This is awarded for the Best Screenplay and/or for the Best Technical Contribution (cinematography, music, etc.)

- Marcello Mastroianni Award

Instituted in 1998 in honor of the great Italian actor Marcello Mastroianni who died in 1996, the award was created to acknowledge an emerging actor or actress[21]

- Special Lion, awarded for an overall work to a director or actor of a film presented in the main competition section.

Orizzonti section (Horizons)

This section is open to all "custom-format" works, with a wider view towards new trends in the expressive languages that converge in film.

Starting from the 67th edition of the festival, four awards of the Orizzonti section were established, with additional awards added in subsequent years. The current awards are:[16]

- Orizzonti Award for Best Film

- Orizzonti Award for Best Director

- Special Orizzonti Jury Prize

- Orizzonti Award for Best Actor

- Orizzonti Award for Best Actress

- Orizzonti Award for Best Screenplay

- Orizzonti Award for Best Short Film

Giornate degli Autori

The Giornate degli Autori (formerly Venice Days) is an independent and parallel section founded in 2004 in association with Venice Film Festival. It is modeled on the Directors' Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival. Anac and 100autori which are both associations of Italian film directors and authors are engaged to support and promote the Giornate.

The awards under this sections include:[22]

- Giornate Degli Autori (GDA) Award

- Label Europa Cinema Award

- BNP Paribas People's Choice Award

Lion of the Future (Luigi De Laurentiis)

All the debut feature films in the various competitive sections in the Venice Film Festival, whether in Official Selection or Independent and Parallel Sections, are eligible for this award. The prize is divided equally between the director and the producer.[16]

Glory to the Filmmaker Award

Jaeger-LeCoultre Glory to the Filmmaker Award, organized in collaboration with Jaeger-LeCoultre (2006-2020) and Cartier (2021- today). It is dedicated to personalities who have made a significant contribution to contemporary cinema.[23]

Past awards

- Audience Referendum

In the first edition of the festival in 1932, due to the lack of a jury and the awarding of official prizes, a list of acknowledgements was decided by popular vote, a tally determined by the number of people flocking to the films, and announced by the Organizing Committee. From this, the Best Director was declared ‚Äď Russian Nikolai Ekk for the film Road to Life, while the film by Ren√© Clair √Ä Nous la Libert√© was voted Best Film.[10]

- Mussolini Cup (Coppa Mussolini)

The Mussolini Cup was the top award from 1934 to 1942 for Best Italian and Best Foreign Film. Named after Italy's dictator Benito Mussolini, it was abandoned upon his ousting in 1943.[23]

- Great Gold Medals of the National Fascist Association for Entertainment "Le Grandi Medaglie d’Oro dell’Associazione Nazionale Fascista dello Spettacolo" in Italian.

These were awarded to Best Actor and Best Actress. The medals were later replaced by the Volpi Cup for actors and actresses.[10]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Marijke de Valck, Brendan Kredell, and Skadi Loist (eds.), Film Festivals: History, Theory, Method, Practice (Routledge, 2016, ISBN 978-0415712477).

- ‚ÜĎ 50 unmissable film festivals Variety, September 7, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Felicia Chan, The international film festival and the making of a national cinema Screen 52(2) (Summer 2011): 253‚Äď260. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 4.0 4.1 4.2 From the beginnings until the Second World War 1893 ‚Äď 1945 La Biennale di Venezia. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Italian Fascism's Empire Cinema (Indiana University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0253015525).

- ‚ÜĎ 6.0 6.1 Christel Taillibert and John W√§fler, Groundwork for a (pre)history of film festivals New Review of Film and Television Studies 14(1) (2016): 5-21. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 7.0 7.1 Christopher Hibbert, Venice: The Biography of a City (HarperCollins, 1990, ISBN 978-0246136367).

- ‚ÜĎ 8.0 8.1 Archivio Storico delle Arti Contemporanee ASAC Dati. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 History of the Venice Film Festival La Biennale di Venezia. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Venice Film Festival History - The 30s La Biennale di Venezia. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Marla Stone, "The Last Film Festival: The Venice Biennale Goes to War" in Jacqueline Reich and Piero Garofalo (eds.), Re-viewing Fascism: Italian Cinema, 1922-1943 (Indiana University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0253215185), 293‚Äď314.

- ‚ÜĎ Brian Moeran and Jesper Strandgaard Pedersen, Negotiating Values in the Creative Industries: Fairs, Festivals and Competitive Events (Cambridge University Press, 2011, ISBN 1107004500).

- ‚ÜĎ Catherine Shoard, Best program ever: Mike Leigh, Coens and Cuaron set for Venice film festival The Guardian, November 12, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Nick Vivarelli, Venice Film Festival winner list Variety, September 8, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 15.0 15.1 79th Festival La Biennale di Venezia. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Regulations La Biennale di Venezia. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ The post-war period: 1948 - 1973 La Biennale di Venezia. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 25 Must-See Films That Won the Venice Film Festival IndieWire, August 28, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ History of the Venice Film Festival ‚Äď The 60‚Äôs and the 70‚Äôs HollywoodGlee, August 13, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Kayleigh Donaldson, Joker's Insane Venice Film Festival Win Explained Screen Rant, September 11, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Marcello Mastroianni Award Carnival of Venice. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ The Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA) Award La Biennale di Venezia. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 23.0 23.1 Venice Film Festival: The 1930‚Äôs Carnival of Venice. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ben-Ghiat, Ruth. Italian Fascism's Empire Cinema. Indiana University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0253015525

- de Valck, Marijke, Brendan Kredell, and Skadi Loist (eds.). Film Festivals: History, Theory, Method, Practice. Routledge, 2016. ISBN 978-0415712477

- Hibbert, Christopher. Venice: The Biography of a City. HarperCollins, 1990. ISBN 978-0246136367

- Moeran, Brian, and Jesper Strandgaard Pedersen. Negotiating Values in the Creative Industries: Fairs, Festivals and Competitive Events. Cambridge University Press, 2011. ISBN 1107004500

- Reich, Jacqueline, and Piero Garofalo (eds.). Re-viewing Fascism: Italian Cinema, 1922-1943. Indiana University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0253215185

- Wong, Cindy Hing-Yuk. Film Festivals: Culture, People, and Power on the Global Screen. Rutgers University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0813550657

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- La Biennale di Venezia

- Venice International Film Festival history

- Venice Film Festival Overview IMDb

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.