| Toshirō Mifune | |

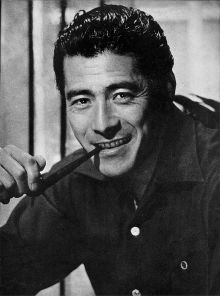

Toshirō Mifune - detail from movie poster of movie Scandal (1950) | |

| Date of birth: | 1 1920 |

| Birth location: | Qingdao, China |

|---|---|

| Date of death: | December 24 1997 (aged 77) |

| Death location: | Mitaka, Japan |

| Spouse: | Sachiko Yoshimine (1950-1995) |

Toshirō Mifune (三船 敏郎 Mifune Toshirō [miɸɯne toɕiɺoː], April 1, 1920 – December 24, 1997) was a Japanese actor who appeared in almost 170 post-World War II feature films. Born in Manchuria, he was drafted into the Japanese military, where he taught aerial photography during World War II. After the war he applied for a job as a cameraman at Toho Studios, where he was hired as an actor and was soon collaborating with director Akira Kurosawa. Their film Rashomon won the Grand Prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1951, assuring international fame for both Kurosawa and Mifune.

Most of the sixteen Kurosawa–Mifune films are considered cinema classics, including Rashomon, Stray Dog, Seven Samurai, The Hidden Fortress, High and Low, Throne of Blood (an adaptation of Shakespeare's MacBeth), Yojimbo, and Sanjuro. Mifune often portrayed a gruff-voiced, coarse and unpredictable samurai or ronin. Mifune has been credited with originating the "roving warrior" archetype. He also appeared in dozens of films by other directors, including several international movies and an American television production, Shogun (1980).

Childhood

Toshirō Mifune was born April 1, 1920, in Qingdao, China, to Japanese parents, and grew up in the Chinese city of Dalian wtih his parents and two siblings.[1] In his youth, Mifune worked in the photography shop of his father Tokuzo Mifune, a commercial photographer and importer who had emigrated from northern Japan. Tokuzo was a Methodist, and there is evidence that he may have also been a missionary, ministering to the ethnic Japanese Christians in Dalian.

Mifune’s father trained him as a photographer. Although Mifune spent the first 19 years of his life in China, as a Japanese citizen he was drafted into the Imperial Japanese Air Force, where he served in the Aerial Photography (Ko-type) unit during World War II, teaching aerial photography and analyzing aerial photographs. He repatriated to Japan in 1946.

Entry into show business

During the war, Mifune had met a movie cameraman who worked for Toho Studios. In 1947, this friend helped him apply for a position as an assistant cameraman in the Photography Department of Toho Productions. There were hundreds of applicants, and after a month he was called for an interview with a panel of three judges:

He is asked to laugh.. "Laugh? What is this? I came for a job." If he wants to audition, he has to laugh, he is told. Somehow his application has been misdirected, and he has found himself auditioning in the studio's "new faces" talent hunt, one of four thousand applicants. "I can't just laugh," he replies curtly, beginning to get angry. ... The interviewers, impatient with his arrogant stubbornness, dismiss him. But one of them, an elderly white-haired gentleman with a mustache, persuades the other judges to call him back - that sort of seething hostility is just what they should be looking for. Next they ask him to play drunk. Another fellow, tall and younger than the others, wearing a floppy hat, has entered the room to watch the audition. The young man thinks this is getting a little silly. He doesn't want to be an actor; he's here for a real job. But "drunk" is something he knows.[2]

Mifune's portrayal of a drunk is spot on, and he is hired. It turns out that:

The white-haired gentleman is Kajiro Yamamoto, one of Toho's leading directors, and the man in the floppy hat is Akira Kurosawa. He had been working on an adjoining set, and had been called over by several actors to watch the brash young man audition. He was mightily impressed by what he saw, and thus began one of the most fruitful collaborations between an actor and director in cenema.[2]

Fortunately, an actress who had observed the audition sought out the famous director, Akira Kurosawa, during lunch break, and told him about the interesting young man she had seen there. Kurosawa attended the afternoon audition. Instructed to mime anger, Mifune drew from his wartime experiences. The judges were doubtful, but Kurosawa recalled, in his autobiography, "A young man was reeling around the room in a violent frenzy…. I found this young man strangely attractive." With Kurosawa’s support, Mifune was hired as an actor. Yamamoto took a liking to him, and recommended him to director Senkichi Taniguchi. This led to Mifune's first feature role, in Shin Baka Jidai (1947; “These Foolish Times”). In 1948 he received critical acclaim for his role as the gangster in Kurosawa's box-office success, Yoidore tenshi (Drunken Angel).

Marriage

Among the 32 women chosen during the New Faces Contest, was the actress Sachiko Yoshimine. Eight years younger than Mifune, she came from a respected Tokyo family. They fell in love and Mifune soon proposed marriage. Yoshimine's parents were strongly opposed to the union. Mifune was an outsider, a non-Buddhist as well as a native Manchurian. His profession also made him suspect, as actors were generally assumed to be irresponsible and financially incapable of supporting a family.

Director Senkichi Taniguchi, with the help of Akira Kurosawa, convinced the Yoshimine family to allow the marriage. It took place in February of 1950. In November of the same year, their first son Shiro was born. In 1955, they had a second son, Takeshi. Mifune's daughter Mika was born to his mistress, actress Mika Kitagawa, in 1982.

International recognition

Mifune first attracted international attention for his role as a boastful bandit in the classic film Rashomon (1950), the story of a crime told from several points of view. The film won the Golden Lion (Grand Prize) at the Venice Film Festival in 1951, and also an Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. Rashomon was a box-office failure in Japan, and neither Kurosawa or Mifune knew that it had been submitted to the Venice Film Festival. In Japan, their success received almost no publicity. Rashomon was the first Japanese film to make an impact in the West, and achieved global recognition for both Kurosawa and Mifune.

Popularity

Mifune’s “angry young man” persona appealed to Japanese film-makers, who were liberating themselves from the strict censorship imposed on them by the Japanese government during World War II.

In his 1982 memoir, Something Like an Autobiography, Kurosawa wrote of him:

"Mifune had a kind of talent I had never encountered before in the Japanese film world. It was, above all, the speed with which he expressed himself that was astounding. The ordinary Japanese actor might need ten feet of film to get across an impression; Mifune needed only three. The speed of his movements was such that he said in a single action what took ordinary actors three separate movements to express. He put forth everything directly and boldly, and his sense of timing was the keenest I had ever seen in a Japanese actor. And yet with all his quickness, he also had surprisingly fine sensibilities." [3]

Mifune often portrayed a samurai or ronin, who was usually coarse and gruff, inverting the popular stereotype of the genteel, clean-cut samurai. (Kurosawa once explained that the only weakness he could find with Mifune and his acting ability was his "rough" voice.) In films such as Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, he played characters who were comically lacking in manners, but replete with practical wisdom and experience, understated nobility, and, in the case of Yojimbo, unmatched fighting prowess. Sanjuro, in particular, contrasts this earthy warrior spirit with the useless, sheltered propriety of the court samurai. Kurosawa valued Mifune highly for his effortless portrayal of unvarnished emotion. On the other hand, his portrayal of Musashi Miyamoto in Hiroshi Inagaki's Samurai Trilogy is deliberately the epitome of samurai honor and etiquette.

Mifune was famous for his self-deprecating sense of humor, which often found its way into his film roles. He was renowned for the effort he put into his performances. To prepare for Seven Samurai and Rashomon, Mifune reportedly studied footage of lions in the wild; for Ánimas Trujano, he studied tapes of Mexican actors speaking, so he could recite all his lines in Spanish.

Mifune and Kurosawa

Most of the sixteen Kurosawa–Mifune films are considered cinema classics. These include Rashomon, Stray Dog, Seven Samurai, The Hidden Fortress, High and Low, Throne of Blood (an adaptation of Shakespeare's MacBeth), Yojimbo, and Sanjuro. (See filmography, below) Mifune once said of Akira Kurosawa, "I am proud of nothing I have done other than with him."

Mifune's vivid character portrayals became synonymous with Kurosawa’s prototype of a complex and unpredictable samurai. Mifune starred in Kurosawa's adaptations of three Western literary classics: Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Idiot, titled Hakuchi (1951); Shakespeare's Macbeth. titled Kumonosu-jo (1957; Throne of Blood); and Maxim Gorky's play The Lower Depths, titled Donzoko (1957). Mifune also appeared in Tengoku to jigoku (1963; High and Low), a detective thriller; and Akahige (1965; Red Beard).

Mifune and Kurosawa parted ways after the filming of Red Beard. Several factors contributed to the rift that ended their collaboration. Most of Mifune's contemporaries acted in several different movies throughout the year. Since Red Beard required Mifune to grow a natural beard—one he had to keep for the entirety of the film's two years of shooting—he was unable to act in any other films during the production. This put Mifune and his financially strapped production company deeply into debt, creating friction between him and Kurosawa. Although Red Beard played to packed houses in Japan and Europe, which helped Mifune recoup some of his losses, after the film's release, the two men's' careers took different directions. Mifune continued to enjoy success with a range of samurai and war-themed films, including Rebellion, Samurai Assassin, and The Emperor and a General. Kurosawa's output of films dwindled and drew mixed responses. In 1980, when Mifune achieved popularity with mainstream American audiences through his role as Lord Toranaga in the television miniseries Shogun, Kurosawa publicly made derisive remarks about Shogun.

The relationship between the two men remained ambivalent. While Kurosawa made some very uncharitable comments about Mifune's acting, he also admitted in an interview in Interview magazine that, “all the films that I made with Mifune, without him, they would not exist.” He also presented Mifune with the Kawashita award which he himself had won two years prior. They finally reconciled in 1993 at the funeral of their friend Ishiro Honda, tearfully embracing one another. They never collaborated again, however, nor did they have a chance to fully restore their friendship. Kurosawa and Mifune died within a year of each other.

Mifune also worked with other notable directors, such as Kenji Mizoguchi, considered my many modern film critics to be the greatest Japanese director of all, in The Life of Oharu (1952), and Hiroshi Inagaki in his samurai trilogy.

Western films

Mifune's imposing bearing, acting range, facility with foreign languages and lengthy partnership with acclaimed director Akira Kurosawa made him the most famous Japanese actor of his time, and easily the best known to Western audiences.

In his earliest film roles in English like Grand Prix, made in 1966, Mifune learned his lines phonetically. This was only partially successful, and his voice was often dubbed by Paul Frees. By the time he made Red Sun in 1971, he had become somewhat more proficient in the language and his voice is heard throughout this multinational western. He was always disappointed that he did not have a greater career in the West. His most prominent English-language role was probably that of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in Midway.

Early in the development of Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, director George Lucas reportedly considered Mifune for the role of Obi-Wan Kenobi. Mifune had played an analogous role, (General Rokurota), in The Hidden Fortress, a film greatly admired by Lucas. Its plot and characters have some parallels that Lucas incorporated in his first Star Wars film.

Later life

Early in the 1980s, Mifune founded an acting school, Mifune Geijutsu Gakuin (三船芸術学院). The school failed after only three years.

Mifune received his greatest acclaim in the West after playing Toranaga in the 1980 miniseries Shogun. However, the series' historically accurate yet blunt portrayal of the Japanese shogunate, and the greatly abridged version shown in Japan, meant that it was not as well received in his homeland.

In an 1986 interview with Gerald Peary (The Globe and Mail, June 6, 1986), Mifune described himself: "I still ride horses and do a lot of laughing. But I was born this way. I can't help it. When I was young, I played old men's roles. But now I'm a little boy!" He enjoyed shooting and swordplay. He owned a cabin cruiser and several cars, including a Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud 1962-Type, bought when he acted in "Grand Prix," and an MG-TD 1952-Type which he owned for 45 years.

In 1992, Mifune began suffering from a serious unknown health problem. It has been variously suggested that he destroyed his health with overwork, suffered a heart attack, or experienced a stroke. For whatever reason, he abruptly retreated from public life and remained largely confined to his home, cared for by his estranged wife Sachiko. When she succumbed to pancreatic cancer in 1995, Mifune's physical and mental state began to decline rapidly. He died in Mitaka, Japan, on December 24, 1997, of multiple organ failure.

Legacy

Mifune has been credited as originating the "roving warrior" archetype, which he perfected during his collaboration with Kurosawa. Mifune, playing the gruff-voiced, ill-mannered hero who nonetheless exhibited cunning, strength, loyalty, integrity, courage and compassion, influenced the development of a similar heroic character type in Western films. This hero attracted the attention of the audience by demonstrating internal strength of character, not a handsome and well-mannered exterior. Clint Eastwood was among the first of many American actors to adopt this persona, which he used to great effect in his Western roles, especially the "spaghetti westerns" made with Sergio Leone.

Of Toshiro Mifune, in his 1991 book Cult Movie Stars, Danny Peary wrote,

Vastly talented, charismatic, and imposing (because of his strong voice and physique), the star of most of Akira Kurosawa's classics became the first Japanese actor since Sessue Hayakawa to have international fame. But where Hayakawa became a sex symbol because he was romantic, exotic, and suavely charming (even when playing lecherous villains), Mifune's sex appeal – and appeal to male viewers – was due to his sheer unrefined and uninhibited masculinity. He was attractive even when he was unshaven and unwashed, drunk, wide-eyed, and openly scratching himself all over his sweaty body, as if he were a flea-infested dog. He did indeed have animal magnetism – in fact, he based his wild, growling, scratching, superhyper Samurai recruit in The Seven Samurai on a lion. It shouldn't be forgotten that Mifune was terrific in Kurosawa's contemporary social dramas, as detectives or doctors, wearing suits and ties, but he will always be remembered for his violent and fearless, funny, morally ambivalent samurai heroes for Kurosawa, as well as in Hiroshi Inagaki's classic epic, The Samurai Trilogy.[4]

Peary also wrote,

Amazingly physical, [Mifune] was a supreme action hero whose bloody, ritualistic, and, ironically, sometimes comical sword-fight sequences in Yojimbo and Sanjuro are classics, as well-choreographed as the greatest movie dances. His nameless sword-for-hire anticipated Clint Eastwood's 'Man With No Name' gunfighter. With his intelligence, eyes seemingly in back of his head, and experience evident in every thrust or slice, he has no trouble – and no pity – dispatching twenty opponents at a time (Bruce Lee must have been watching!). It is a testament to his skills as an actor that watching the incredible swordplay does not thrill us any more than watching his face during the battle or just the way he moves, without a trace of panic, across the screen – for no one walks or races with more authority, arrogance, or grace than Mifune's barefoot warriors. For a 20-year period, there was no greater actor – dynamic or action – than Toshiro Mifune. Just look at his credits.[4]

In an article published in 2020 by The Criterion Collection in commemoration of Mifune's centenary of birth, Moeko Fujii wrote:

For most of the past century, when people thought of a Japanese man, they saw Toshiro Mifune. A samurai, in the world's eyes, has Mifune's fast wrists, his scruff, his sidelong squint... He may have played warriors, but they weren't typical heroes: they threw tantrums and fits, accidentally slipped off mangy horses, yawned, scratched, chortled, and lazed. But when he extended his right arm, quick and low with a blade, he somehow summoned the tone of epics.

There's a tendency to make Mifune sound mythical. The leading man of Kurosawa-gumi, the Emperor's coterie, he would cement his superstar status in over 150 films in his lifetime, acting for other famed directors — Hiroshi Inagaki, Kajiro Yamamoto, Kihachi Okamoto — in roles ranging from a caped lover to a Mexican bandit.

Mifune's life on-screen centers solely around men. Women, when they do appear, feel arbitrary, mythical, temporary: it's clear that no one is really invested in the thrums of heterosexual desire... Mifune never wants the girl in the first place. So the men around him can't help but watch him a little open-mouthed, as he walks his slice of world, amused by and nonchalant about the stupor he leaves in his wake. "Who is he?," someone asks, and no one ever has a good answer. You can't help but want to walk alongside him, to figure it out.[5]

Honors

Mifune was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure by the Japanese government in 1993, and a posthumous Hollywood Walk of Fame star in 2016.[6]

Filmography

Due to variations in translation from the Japanese and other factors, there are multiple titles to many of Mifune's films. The titles shown here are the most common titles used in the United States.

- 1947 Snow Trail - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1947 These Foolish Times - Parts 1 & 2 - directed by Kajiro Yamamoto

- 1948 Drunken Angel - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1949 The Quiet Duel - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1949 Jakoman and Tetsu - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1949 Stray Dog - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1950 Escape at Dawn - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1950 Conduct Report on Professor Ishinaka - Directed by Mikio Naruse

- 1950 Scandal - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1950 Engagement Ring - directed by Keisuke Kinoshita

- 1950 Rashomon - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1951 Beyond Love and Hate - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1951 Elegy - directed by Kajiro Yamamoto

- 1951 The Idiot - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1951 Pirates - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1951 Meeting of the Ghost Après-Guerre - directed by Kiyoshi Saeki

- 1951 Conclusion of Kojiro Sasaki-Duel at Ganryu Island directed by Hiroshi Inagaki - This was the first, but not the last, time that Mifune played Musashi Miyamoto

- 1951 The Life of a Horsetrader - directed by Keigo Kimura

- 1951 Who Knows a Woman's Heart - directed by Kajiro Yamamoto

- 1952 Vendetta for a Samurai - directed by Kazuo Mori

- 1952 Foghorn - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1952 The Life of Oharu - directed by Kenji Mizoguchi

- 1952 Jewels in our Hearts - directed by Yasuke Chiba

- 1952 Swift Current - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1952 The Man Who Came to Port - directed by Ishiro Honda

- 1953 My Wonderful Yellow Car - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1953 The Last Embrace - directed by Masahiro Makino

- 1953 Love in a Teacup - directed by Yasuke Chiba

- 1953 The Eagle of the Pacific - directed by Ishiro Honda

- 1954 Seven Samurai - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1954-56 Samurai Trilogy - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1954 Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto

- 1955 Samurai II: Duel at Ichijoji Temple

- 1956 Samurai III: Duel at Ganryu Island

- 1954 The Sound of Waves - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1954 The Black Fury - directed by Toshio Sugie

- 1955 A Man Among Men - directed by Kajiro Yamamoto

- 1955 All is Well - Part 1 & 2 - directed by Toshio Sugie

- 1955 No Time for Tears - directed by Seiji Maruyama

- 1955 Record of a Living Being aka I Live in Fear - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1956 Rainy Night Duel - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1956 The Underworld - directed by Kajiro Yamamoto

- 1956 Settlement of Love - directed by Shin Saburi

- 1956 A Wife's Heart - directed by Mikio Naruse

- 1956 Scoundrel - directed by Nabuo Aoyagi

- 1956 Rebels on the High Seas - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1957 Throne of Blood aka Spider Web Castle - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1957 A Man in the Storm - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1957 Be Happy These Two Lovers - directed by Ishiro Honda

- 1957 Yagyu Secret Scrolls - part 1 - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1957 A Dangerous Hero - directed by Hideo Suzuki

- 1957 The Lower Depths - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1957 Downtown - directed by Yasuki Chiba

- 1958 Yagyu Secret Scrolls - part 2 - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1958 Tokyo Holiday - directed by Kajiro Yamamoto

- 1958 Muhomatsu, The Rikshaw Man - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1958 The Happy Pilgrimage - directed by Yasuki Chiba

- 1958 All About Marriage - uncredited cameo - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1958 Theater of Life - directed by Toshio Sugie

- 1958 The Hidden Fortress - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1959 Boss of the Underworld - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1959 Samurai Saga - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1959 The Saga of the Vagabonds - directed by Toshio Sugie

- 1959 Desperado Outpost - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1959 The Birth of Japan - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1960 The Last Gunfight - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1960 The Gambling Samurai - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1960 The Storm Over the Pacific - directed by Shuei Matsubayashi

- 1960 Man Against Man - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1960 The Bad Sleep Well - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1960 The Masterless 47 - part 1 - directed by Toshio Sugie

- 1961 The Story of Osaka Castle - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1961 The Masterless 47 - part 2 - directed by Toshio Sugie

- 1961 Yojimbo aka The Bodyguard - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1961 The Youth and his Amulet - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1962 Ánimas Trujano aka The Important Man - directed by Ismael Rodríguez

- 1962 Sanjuro - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1962 Tatsu - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1962 Chushingura - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1963 Wings over the Pacific - directed by Shue Matsubayashi

- 1963 High and Low aka Heaven and Hell - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1963 Legacy of the 500,000 - directed by Toshiro Mifune

- 1963 The Great Thief - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1964 Whirlwind - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1965 Samurai Assassin aka Samurai - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1965 Red Beard - directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1965 Sanshiro Sugata - directed by Seiichiro Uchikiro - this is a remake of Kurosawa's films Sanshiro Sugata and Sanshiro Sugata part 2

- 1965 Retreat from Kiska - directed by Seiji Maruyama

- 1965 Fort Graveyard - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1966 Wild Goemon - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1966 The Sword of Doom - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1966 The Adventure of Kigan Castle - directed by Senkichi Taniguchi

- 1966 The Mad Atlantic - directed by Jun Fukuda

- 1966 Grand Prix - directed by John Frankenheimer - This was Mifune's first English language film, and learned his English lines phonetically. It is reported that his voice was used at the premiere. All versions of the film after that are dubbed by Paul Frees, except for the scenes where he is speaking Japanese.

- 1967 Samurai Rebellion - directed by Masaki Kobayashi

- 1967 The Longest Day of Japan - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1968 The Sands of Kurobe - directed by Kei Kumai

- 1968 Admiral Yamamoto - directed by Eiji Tsuburaya

- 1968 Gion Festival - directed by Daisuke Ito and Tetsuya Yamanouchi

- 1968 Hell in the Pacific - directed by John Boorman This was filmed with different endings for the U.S. and Japanese releases. Both are available on current video releases.

- 1969 Samurai Banners - directed by Hiroshi Inagaki

- 1969 5,000 Kilometers to Glory - directed by Koreyoshi Kurahara

- 1969 Battle of the Japan Sea - directed by Seiji Maruyama

- 1969 Red Lion - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1969 Band of Assassins - directed by Tadashi Sawashima

- 1970 Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo - directed by Kihachi Okamoto

- 1970 The Ambitious - directed by Daisuke Ito

- 1970 Incident at Blood Pass - directed by Hiroshi Inigaki

- 1970 The Walking Majo - directed by Koji Senno, Nobuaki Shirai and Keith Eric Burt

- 1970 The Militarists - directed by Hiromichi Horikawa

- 1971 Red Sun - directed by Terence Young - not released in the U.S. until 1972

- 1975 Paper Tiger - directed by Ken Annakin

- 1975 Midway - directed by Jack Smight

- 1977 Proof of the Man - directed by Junya Sato

- 1977 Japanese Godfather: Ambition - directed by Sadao Nakajima

- 1977 Shogun's Samurai - directed by Kinji Fukasaku

- 1978 Dog Flute - directed by Sadao Nakajima

- 1978 Lady Ogin - directed by Kei Kajima

- 1978 Japanese Godfather: Conclusion - directed by Sadao Nakajima

- 1978 The Fall of Ako Castle - directed by Kinji Fukasaku

- 1978 Lord Incognito - directed by Tetsuya Yamauchi

- 1979 Winter Kills - directed by William Richart

- 1979 The Adventures of Kosuke Kindaichi - directed by Nobuhiku Kobayashi

- 1979 Secret Detective Investigation-Net in Big Edo - directed by Akinori Matsuo

- 1979 1941 - directed by Steven Spielberg

- 1981 The Bushido Blade - directed by Tsugunobu Kotani

- 1981 Port Arthur - directed by Toshio Masuda

- 1981 Shogun - directed by Jerry London - this was shown on television in the U.S. and as a theatrical version in the rest of the world

- 1981 Inchon! - directed by Terence Young

- 1982 The Challenge - directed by John Frankenheimer

- 1983 Conquest - directed by Sadao Nakajima

- 1983 Theater of Life - directed by Sadao Nakajima, Junya Sato and Kinji Fukasaku

- 1983 Battle Anthem - directed by Toshio Masuda

- 1984 The miracle of Joe the Petrel - directed by Toshiya Fujita

- 1985 Legend of the Holy Woman - directed by Toru Murakawa

- 1986 Song of Genkai Tsurezure - directed by Masanobu Deme

- 1987 Shatterer - directed by Tonino Valerii

- 1987 Tora-san Goes North - directed by Yoji Yamada

- 1987 Princess from the Moon - directed by Kon Ichikawa

- 1989 Demons in Spring - directed by Akira Kobayashi

- 1989 Death of a Tea Master - directed by Kei Kumai

- 1989 cf Girl - directed by Izo Hashimoto

- 1991 Strawberry Road - directed by Koreyoshi Kurihara

- 1992 Helmet - directed by Gordon Hessler

- 1992 Shadow of the Wolf - directed by Jacques Dorfman

- 1994 Picture Bride - directed by Kayo Hatta

- 1995 Deep River - directed by Kei Kumai

Television Appearances

All shows aired in Japan except for Shogun which aired in the U.S.

- 1968 The Masterless Samurai - 6 one hour episodes

- 1971 Daichūshingura - 52 one hour episodes

- 1972 Ronin of the Wilderness - 104 one hour episodes

- 1973 Yojimbo of the Wilderness - 5 one hour episodes

- 1976 The Sword, The Wind and the Lullaby - 27 one hour episodes

- 1977 Ronin in a Lawless Town - 23 one hour episodes

- 1978 The Spy Appears - 5 one hour episodes

- 1978 An Eagle in Edo - 38 one hour episodes

- 1979 Hideout in a Suite - 11 one hour episodes

- 1980 Shogun - parts 1 & 5 159 minutes parts 2-4 93 minutes

- 1981 Sekigahara - one seven hour episode

- 1981 Bungo's Detective Notes - 3 one hour episodes

- 1981 The Ten Battles of Shingo - 2 one hour episodes

- 1981 My Daughter! Fly on the Wings of Love and Tears - 1 two hour episode

- 1981 The Crescent Shaped Wilderness - 1 two hour episode

- 1982 The Ronin's Path - 5 two hour episodes

- 1982 The Happy Yellow Handkerchief - 1 two hour episode

- 1983 The Brave Man Says Little - 1 eight hour episode

- 1983 The Ronin's Path vol. 5 - 1 one hour episode

- 1983 Ronin-Secret of the Wilderness Valley - 1 one hour episode

- 1984 Soshi Okita, Burning Corpse of a Sword Master - 1 one hour episode

- 1984 The Burning Mountain River - 51 episodes

Notes

- ↑ Matthew Hernon, Spotlight: Toshiro Mifune — Japan’s Greatest Ever Actor Tokyo Weekender (August 5, 2023). Retrieved June 14, 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 David Owens, Toshiro Mifune Biography Japan Society's 1984 film tribute. Retrieved June 14, 2025.

- ↑ Akira Kurosawa, Something Like An Autobiography (Vintage, 1983, ISBN 978-0394714394).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Danny Peary, Cult Movie Stars (Fireside, 1991, ISBN 978-0671693947).

- ↑ Moeko Fujii, Who's That Man? Mifune at 100 The Criterion Collection, April 3, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2025.

- ↑ Toshiro Mifune: The Wolf of Japanese Cinema Movie Star History. Retrieved June 14, 2025.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Asahi Shinbunsha. Tsuitō Mifune Toshirō: otoko. Tōkyō: Asahi Shinbunsha, 1998. (Japanese)

- Galbraith, Stuart. The Emperor and the wolf: the lives and films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. New York: Faber and Faber, 2002. ISBN 0571199828

- Galloway, Patrick. Stray dogs & lone wolves: the samurai film handbook. Berkeley, Calif: Stone Bridge Press, 2005. ISBN 1880656930

- Japan Society (New York, NY). The Japan Film Center presents a tribute to Toshiro Mifune: 40 films starring Japan's greatest actor : March 7-April, 29, 1984. New York: Japan Society.

- Kurosawa, Akira. Something Like An Autobiography. Vintage, 1983. ISBN 978-0394714394

- Peary, Danny. Cult Movie Stars. Fireside, 1991. ISBN 978-0671693947

- Richie, Donald. A hundred years of Japanese film: a concise history with selective guide to videos and DVDs. Foreword by Paul Schrader. Tokyo [u.a.]: Kodansha International, 2001. ISBN 477002682X

External links

All links retrieved June 14, 2025.

- Toshirō Mifune - Tribute Site

- Toshirō Mifune at the Internet Movie Database

- Toshirō Mifune at the Japanese Movie Database

- Mifune Toshirō, a World-Class Act Nippon Communications Foundation

- Toshiro Mifune: 10 essential films British Film Institute

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.