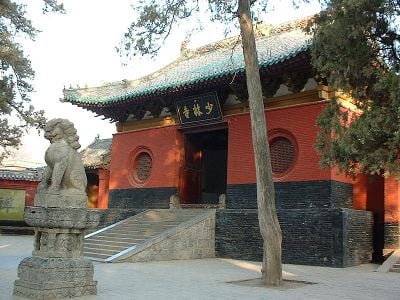

The Shaolin Monastery or Shaolin Temple (Chinese: ć°æćŻș; pinyin: ShĂ olĂnsĂŹ), is a Chan Buddhist temple at Song Shan in Zhengzhou City, Henan Province, of what is now the People's Republic of China. The monastery was built by the Emperor Hsiao-Wen in 477 C.E., and the first abbot of Shaolin was Batuo, (also, Fotuo or Bhadra (the Chinese transposition of Buddha), an Indian dhyana master who came to China in 464 C.E. to spread Buddhist teachings.[1] Another Indian Monk, Bodhidharma, or Da Mo, is said by the Shaolin monks to have introduced Chan Buddhism (similar to Japanese Zen Buddhism) at Shaolin Temple in 527 C.E. Bodhidharma also taught what the monks called â18 Hands of the Lohan,â physical exercises which are said to be the origin of tai chi chuan and other methods of fighting without weapons, such as kung fu. According to legend Bodhidharma meditated in solitude for nine years facing the wall of a cave above the monastery, and remained immobile for so long that the sun burned his outline onto a stone, which can still be seen. The Temple's historical architectural complex, standing out for its great aesthetic value and its profound cultural connotations, was designated a World Heritage Site in 2010.

The Shaolin Monastery is the Mahayana Buddhist monastery perhaps best known to the Western world, because of its long association with Chinese martial arts and particularly with Shaolin kung fu[2] The story of the five fugitive monks Ng Mui, Jee Shin Shim Shee, Fung Doe Duk, Miu Hin and Bak Mei, who spread Shaolin martial arts through China after the Shaolin Temple was destroyed in 1644 by the Qing government, commonly appears in martial arts history, fiction, and cinema.

Name

The Shao in "Shaolin" refers to "Mount Shaoshi," a mountain in the Songshan mountain range. The lin in "Shaolin" means "forest." Literally, the name means "Monastery in the woods of Mount Shaoshi."

Location

Shaolin Monastery is located in Henan Province, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) southeast of Luoyang and 55 miles (88 kilometers) southwest of Zhengzhou at the western edge of Songshan. The central of China's four sacred Taoist peaks, Mount Song is also known as the âMiddle Holy Mountain.â Emperor Wu Di of the Han dynasty visited this mountain in 110 B.C.E.. Emperors of succeeding dynasties came in person or sent special envoys to pay homage to Mount Song, and many memorial halls, Buddhist and Daoist Temples, stone arches and inscribed tablets have been erected there over the years.

The Shaolin Monastery, which still houses 70 monks, is now a major tourist attraction, as well as a place of pilgrimage for monks and lay Buddhists. A training hall has been built next to the monastery for foreigners who come to study Buddhism and martial arts. One of its greatest treasures is 18 frescoes, painted in 1828, depicting ancient monks in classic fighting poses.[3]

History

Early history

According to the Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks (645 C.E.) by DĂ oxuÄn, the Shaolin Monastery was built on the north side of Shaoshi, the western peak of Mount Song, one of the Sacred Mountains of China, in 495 C.E. by Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty. Yang Xuanzhi, in the Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang (547 C.E.), and Li Xian, in the Ming Yitongzhi (1461), concur with Daoxuan's location and attribution.

The Jiaqing Chongxiu Yitongzhi (1843) specifies that this monastery, located in the province of Henan, was built in the 20th year of the Tà ihé era of the Northern Wei Dynasty, that is, the monastery was built in 497 C.E..

The Indian dhyana master Batuo (è·é, BĂĄtuĂł, also, Fotuo or Buddhabhadra) was the first abbot of Shaolin Monastery.[4] According to the Deng Feng County Recording (Deng Feng Xian Zhi), BĂĄtuĂł came to China in 464 C.E. and preached Nikaya (ć°äč) Buddhism for 30 years. In 495, the Shaolin Monastery was built by the order of Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei as a center for Batuoâs teaching. [1]

Kangxi, the second Qing emperor, was a supporter of the Shaolin temple in Henan and he wrote the calligraphic inscription that, to this day, hangs over the main temple gate.

Bodhidharma

In 527 C.E. another Indian Monk, Bodhidharma, or Da Mo, arrived at Shaolin Monastery. According to the Song of Enlightenment, (èéæ ZhĂšngdĂ o gÄ) by YÇngjiÄ XuĂĄnjuĂ© (665-713)[5] one of the chief disciples of HuĂŹnĂ©ng, sixth Patriarch of ChĂĄn, Bodhidharma was the 28th Patriarch of Buddhism in a line of descent from ĆÄkyamuni Buddha via his disciple MahÄkÄĆyapa, and the first Patriarch of Chan Buddhism. He is said by the Shaolin monks to have introduced Chan Buddhism (similar to Japanese Zen Buddhism) to them at Shaolin Temple in Henan, China during the sixth century. Bodhidharma also taught what the monks called â18 Hands of the Lohan,â[6] (non-combative healthful exercises), said to be the origin of kung fu martial arts.

According to legend, Bodhidharma meditated in solitude for nine years facing the wall of a cave in the mountains above the monastery. He remained immobile for so long that the sun burned his outline onto a stone, which can still be seen on the wall of the cave.[7]

Martial arts

Shaolin Temple is associated with the development of Chinese martial arts, particularly with Shaolin kung-fu. Various styles of Chinese martial arts, such as Jiao Di (the precursor of Shuai Jiao), Shou Bo kung fu (Shang dynasty), and Xiang Bo (similar to Sanda, from the 600s B.C.E.) are said in some sources to have been practiced even before the Xia dynasty (founded in 2205 B.C.E.).[8] Huiguang and Sengchou, two of the first disciples of BĂĄtuĂł, were accomplished martial artists and are said by some to have been the originators of what would become Shaolin kungfu.[9]

Another story relates that during his nine years of meditation in the cave, Bodhidharma developed a series of exercises using choreographed movements and deep breathing to maintain his physical strength. When he returned to the monastery, he observed that the monks lacked the physical and mental stamina needed to perform Buddhist meditation, and instructed then in the exercises he had developed. (Other legends claim that Bodhidharmaâs legs atrophied because he concentrated so intently during his meditation that he never moved.) The main purpose of Shaolin martial arts training was the promotion of health, strength and mental concentration; it was forbidden to take up arms except to fight evil. These exercise techniques became the origin of tai chi chuan and other methods of fighting without weapons, such as kung fu.

There is evidence that Shaolin martial arts techniques were exported to Japan in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Okinawan ShĆrin-ryĆ« karate (ć°ææ”), for example, is sometimes called "Small [Shao]lin."[10] Other similarities can be seen in centuries-old Chinese and Japanese martial arts manuals.[11]

Battle of the 13 Shaolin monks

In 621 C.E., at the beginning of the Tang dynasty, a warlord and general of the previous Sui dynasty, Wang Shi-chong, captured Li Shan Ming, son of Li Shimin, founder of the Tang-dynasty. Thirteen armed Shaolin monks rescued him at Luo Yang, and drove back Shi-chongâs troops at the battle of Qianglingkou. When Li Shan Ming ascended to the throne as the Taizong emperor, he invited the monks of Shaolin to demonstrate their art at court. The emperor gave a lavish feast and sent a stone tablet engraved with the names of the monks who had saved him to Shaolin. He appointed the head monk, Tang Zong, a general, and rewarded the Temple with an estate of 40 hectares and supplies of grain. The Shaolin Temple was permitted to train 500 warrior monks.

Ming Dynasty

During the Ming dynasty (1368 -1644) Shaolin kung fu flourished. The Temple maintained an army of 2500 men, and innumerable variants and techniques were developed. Monks studied weapons techniques, chi gong, meditation and forms of boxing.

Prohibition of Shaolin kung fu

The Qing dynasty (1644 â 1911) prohibited all combat arts and many monks left the monastery. As they traveled throughout China spreading Buddhism, they observed new kinds of martial arts and brought these techniques back to the temple, where they were integrated into Shaolin kung fu.

Destruction

The monastery has been destroyed and rebuilt many times. It was destroyed in 617 but rebuilt in 627. The best-known story is that of its destruction in 1644 by the Qing government for supposed anti-Qing activities; this event is supposed to have helped spread Shaolin martial arts through China by means of the five fugitive monks Ng Mui, Jee Shin Shim Shee, Fung Doe Duk, Miu Hin and Bak Mei. This story commonly appears in martial arts history, fiction, and cinema.

According to Ju Ke, in the Qing bai lei chao (1917), accounts of the Qing Dynasty destroying the Shaolin temple may refer to a southern Shaolin temple, located in Fujian Province. Additionally, some martial arts historians, such as Tang Hao and Stanley Henning, believe that the story is likely fictional and appeared only at the very end of the Qing period in novels and sensational literature.

Shaolin Temple

The Shaolin Temple complex contains a number of buildings and interesting sites. The first building, the Shanmen Hall, enshrines the Maitreya Buddha. The sides of the corridor behind the hall's gate are lined with inscriptions on stone steles from several dynasties, and two stone lions made in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) crouch under the stairs. The gate of the Hall of Heavenly Kings (Tianwangdian) is guarded by two figures depicting Vajra (Buddhist warrior attendants), and contains figures of the Four Heavenly Kings.

Eighteen Buddhist Arhats stand along the eastern and the southern walls of the Mahavira Hall (Daxiongbaodian, Thousand Buddha Hall), where regular prayers and important celebrations are held. Next to statues of the Buddhas of the Middle, East and West stand the figures of Kingnaro and Bodhiharma. Stone lions more than one meter (about 3.33 feet) high sit at the feet of the pillars. The Hall contains a carved jade sculpture of Amitabha Buddha and a wall painting of the 500 lohan (âworthiesâ) that covers three sides of it. About fifty depressions, each about 20 centimeters (about 7.87 inches) deep, were worn into the floor by monks practicing martial arts.

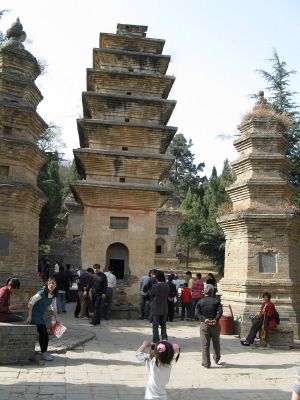

The Pagoda Forest, a graveyard for Buddhist monks, is the largest of China's pagoda complexes. It contains 220 pagodas, averaging less than 15 meters (about 49 feet) in height, with the shape and number of stories in each pagoda indicating the prestige, status and attainment of each monk. A âforest of stelaeâ contains inscriptions by many famous calligraphers, including Su Shi and Mi Fu.

Outside the temple to the northwest are two monasteries, the Ancestor's Monastery and the Second Ancestor's Monastery. The first was built by a disciple of Bodhidharma to commemorate his nine years of meditation in a cave. Its large hall is supported by 16 stone pillars with exquisitely carved warriors, dancing dragons and phoenixes. The second monastery was built for his successor, the âsecond ancestorâ Huike, who cut off his left arm to show the sincerity of his desire to study Buddhism from Dharma. In front of the monastery are four springs called 'Spring Zhuoxi,' said to have been created by Bodidharma so that Huike could easily fetch water; each has its own distinctive flavor.

The Dharma Cave, where Bodhidharma meditated for nine years before founding Chan Buddhism, is seven meters (about 23 feet) deep and three meters (about 9.8 feet) high, carved with stone inscriptions.[12]

Recent history

The current temple buildings date from the Ming (1368 â 1644) and Qing (1644 â 1911) dynasties.

In 1928, the warlord Shi Yousan set fire to the monastery and burned it for over 40 days, destroying 90 percent of the buildings including many manuscripts of the temple library.

The Cultural Revolution launched in 1966 targeted religious orders including the Monastery. The five monks who were present at the Monastery when the Red Guard attacked were shackled and made to wear placards declaring the crimes charged against them. The monks were publicly flogged and paraded through the streets as people threw garbage at them, then jailed. The government purged Buddhist materials from within the Monastery walls, leaving it barren for years.

Martial arts groups from all over the world have made donations for the upkeep of the temple and grounds, and are consequently honored with carved stones near the entrance of the temple.

A Dharma gathering was held between August 19 and 20, 1999, in the Shaolin Monastery to install Buddhist Master Shi Yong Xin as abbot. He is the thirteenth successor after Buddhist abbot Xue Ting Fu Yu. In March, 2006, Vladimir Putin of Russia became the first foreign leader to visit the monastery.

In preparation for the Olympic Games in 2008, the Chinese government completed a new expressway from Zhengzhou to Shaolin, and constructed a large and modern entrance to the temple, housing souvenir shops and a reception hall. Two luxurious bathrooms, reportedly costing three million yuan (US$ 430,000), were added to the temple for use by monks and tourists.

In 2010, several ancient sites around Dengfeng were united into a single UNESCO World Heritage Site, with eight distinct scenic spots. The Shaolin Scenic spot contained three of the WHS components, collectively called the "architectural complex." By this, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) of UNESCO designated three ancient sites: the Shaolin Temple compound, assigned the name "Kernel Compound"; its cemetery, the Pagoda Forest; and its subsidiary, the Chuzu Temple.[13]

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 Order of the Shaolin Ch'an, The Shaolin Grandmaster's Text: History, Philosophy, and Gung Fu of Shaolin Ch'an (Beaverton, OR: 2006).

- â Meir Shahar, "Ming-Period Evidence of Shaolin Martial Practice." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 61(2) (December 2001): 359â413.

- â Songshan Mountain and Shaolin Monastery China.org. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- â Jeffrey L. Broughton, The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0520219724).

- â Chung-Yuan Chang, "Ch'an Buddhism: Logical and Illogical", Philosophy East and West 17 (1967): 37â49.

- â George Takei and Nancy Gimbrone, The Martial Arts (New York: A&E Home Video, 2005).

- â The Story of Bodhidharma USA Shaolin Temple. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- â Kang Gewu, The Spring & Autumn of Chinese Martial Arts: 5,000 Years (Plum Pub., 1995).

- â Salvatore Canzonieri, "History of Chinese Martial arts: Jin Dynasty to the Period of Disunity." Han Wei Wushu 3 9) (FebruaryâMarch 1998).

- â Mark Bishop, Okinawan Karate: Teachers, Styles and Secret Techniques (London: A&C Black, 1989, ISBN 0713656662).

- â Norman Leff, âAtemi Waza,â Martial Arts Legends (April 1999).

- â Songshan Shaolin Travel China Guide. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- â Historic Monuments of Dengfeng in âThe Centre of Heaven and Earthâ UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bishop, Mark. Okinawan Karate: Teachers, Styles and Secret Techniques. London, A&C Black, 1989. ISBN 0713656662

- Broughton, Jeffrey L. The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0520219724

- Gewu, Kang. The Spring & Autumn of Chinese Martial Arts: 5,000 Years. Plum Pub., 1995.

- Leff, Norman. âAtemi Waza,â Martial Arts Legends (April 1999) (magazine). CFW Enterprises.

- Order of the Shaolin Ch'an. The Shaolin Grandmaster's Text: History, Philosophy, and Gung Fu of Shaolin Ch'an. Beaverton, OR: 2006.

- Ć aáž„ar, MÄ'Ăźr. âMing-Period Evidence of Shaolin Martial Practice,â Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 61 (2) (December 2001): 359â413.

- Ć aáž„ar, MÄ'Ăźr. The Shaolin monastery: history, religion, and the Chinese martial arts. Honolulu: Univ. of Hawaii Press, 2008. ISBN 9780824831103

- Salvatore Canzonieri, "History of Chinese Martial arts: Jin Dynasty to the Period of Disunity." Han Wei Wushu 3 (9) (FebruaryâMarch 1998).

- Shahar, Meir. "Ming-Period Evidence of Shaolin Martial Practice." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 61 (2)(December 2001): 359â413.

- Takei, George, and Nancy Gimbrone. The martial arts. New York: A&E Home Video, 2005.

External links

All links retrieved June 10, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.