Pagan Kingdom

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

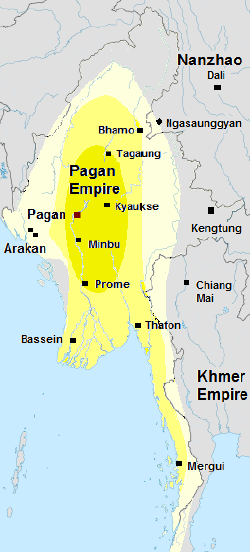

Template:Contains Burmese text The Pagan Kingdom (849-1287) is considered to be the first Burmese empire. During the time of the Pyu kingdom, between about 500 and 950, the Bamar, people of the Burmese ethnic group, began infiltrating from the area to the north into the central region of Burma which was occupied by Pyu people that had come under the influence of Mahayana Buddhism from Bihar and Bengal. By 849, the city of Pagan had emerged as the capital of a powerful kingdom that would unify Burma and filled the void left by the Pyu. The kingdom grew in relative isolation until the reign of Anawrahta, who successfully unified all of Myanmar by defeating the Mon city of Thaton in 1057, inaugurating the Burmese domination of the country that has continued to the present day.

King Kyanzittha (r. 1084 - 1113) and his successor Alaungsithu (r. 1113-1167), consolidated and expanded the Pagan domain, and introduced Mon culture and Theravada Buddhism. They initiated the construction of a large number of temples and religious monuments in the capital of Bagan. The last true ruler of Pagan, Narathihapate (reigned 1254-1287) refused to pay tribute to Kublai Khan and launched an attack on the Mongols in 1277, which resulted in a crushing defeat at the hands of the Mongols in the Battle of Ngasaunggyan. The prosperity and artistic glory of the Pagan Kingdom is attested by the temples and buildings of Bagan. Hundreds of its estimated 3,000 to 4,000 temples and monasteries are still standing. About 2,300 structures are registered by the Archaeological Survey; these are mostly stupas and temples, containing wonderful painting and sculpture from the twelfth through the eighteenth centuries.

Rise of the Pagan Kingdom

Although Anawrahta is credited with the founding of Bagan, the Glass Palace Chronicle ("hman nam ra ja. wang"; IPA: [mÌ„Ă nnĂĄn jĂ zÉwĂŹn]), a compilation of all historical works about Burmese rulers commissioned by King Bagyidaw (1819-1837) in 1829, the "traditional" founder of Bagan was Thamudarit (107 â 152 C.E.). The Glass Palace Chronicle contains many mythical and legendary stories; however, many portions of the chronicle are historically accurate and factual.

During the time of the Pyu kingdom, between about 500 and 950, the Bamar, people of the Burmese ethnic group, began infiltrating from the area to the north into the central region of Burma which was occupied by Pyu people that had come under the influence of Mahayana Buddhism from Bihar and Bengal. By 849, the city of Pagan (now spelled Bagan[1]) had emerged as the capital of a powerful kingdom that would unify Burma and filled the void left by the Pyu. The kingdom grew in relative isolation until the reign of Anawrahta; IPA: [ÉnÉÌjaÌ°tÊ°a]; reigned 1044-1077), also spelled Aniruddha or AnoarahtĂą or Anoa-ra-htĂĄ-soa, who successfully unified all of Myanmar by defeating the Mon city of Thaton in 1057, inaugurating the Burmese domination of the country that has continued to the present day.

Anawrahtaâs father was Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu, who took the throne of Pagan from Nyaung-u Sawrahan and was overthrown in turn by the sons of Nyaung-u Sawrahan, Kyiso and Sokka-te, who forced Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu to become a monk. When Anawrahta came of age, he challenged the surviving brother, Sokka-te, to single combat and slew him. Anawrahta then offered to return the throne to his father, who refused and remained a monk, so he became king in 1044. He made a pilgrimage to Ceylon, and on his return, he converted his country from Ari Buddhism to Theravada Buddhism. To further this goal, he commissioned Shin Arahan, a famous Mon monk of Thaton. In 1057 he invaded Thaton on the grounds that they had refused to lend Pagan the Pali Tripitaka, and successfully returned with the Mon king Manuha as prisoner. From 1057-1059 he took an army to Nanzhao to seek a Buddha's tooth relic. As he returned, Shan chiefs swore allegiance to him, and he married princess Saw Monhla, daughter of the Shan chief of Moguang. In 1071 Anawrahta received the complete Tipitaka from Sri Lanka. Buddhists from Dai regions (southern Yunnan and Laos), Thailand, and India (where Buddhism had been oppressed) came to study in Pagan as Anawrahta moved the center of Burmese Buddhism north from Thaton. He also built the famous Shwezigon Pagoda. Within two centuries, Theravada Buddhism became the dominant religion in Myanmar.

King Sawlu (1077-1084), the son of the King Anawratha, proved to be an incompetent ruler and almost destroyed his kingdom. When Sawlu was a child, Anawrahta appointed Nga Yaman Kan, the son of Sawluâs Arab wet nurse, to be his royal tutor.[2] When Sawlu became king, he appointed Nga Yaman Kan the Governor of Bago (Pegu) known as Ussa City. According to the Glass Palace Chronicle, King Sawlu became angry when Nga Yaman Kan defeated him at a game of dice, jumped with joy and clapped his elbows together. In his anger, he challenged Nga Yaman Kan to prove he was a real man and rebel against him with the Bago province. Nga Yaman Kan accepted the challenge, returned to Bago and marched back to Bagan with his army of soldiers on horses and elephants. Nga Yaman Kan and his army camped at Pyi Daw Thar Island. Nga Yaman Kan was a clever and creative strategist, with a thorough knowledge of the geography of Bagan, and he used this knowledge to his advantage. He successfully trapped Sawluâs half-brother, the general Kyanzittha (who had allegedly fallen in love with Anawrahta's wife-to-be, the Princess of Mon), King Sawlu and his Bagan army in the swamps. The whole Bagan army fled, and Sawlu was found and arrested.[3]

Kyanzittha tried to rescue him, but Sawlu refused to accompany him, calculating that Kyanzittha would kill him to get the throne and that he was safer with his friend Nga Yaman Kan. Nga Yaman Kan then killed Sawlu to prevent the further attempts to rescue him. Nga Yaman Kan himself was ambushed and killed by the sniper arrows of Nga Sin the hunter, and died. [4][5]

Expansion and Consolidation

After the assassination of Sawlu, Kyanzittha was crowned and reigned from 1084 to 1113. He was a son of King Anawrahta and a lesser queen. During his youth, Kyanzittha had participated in the Thaton campaign to obtain the Tripitaka from Mon Kingdom. Kyanzittha was particularly known for his patronage of the Mon culture; during his reign, he left many inscriptions in Mon, married a Mon princess, and established good relations with the Mon kingdom. He is well-known for building a large number of temples and religious monuments in Bagan, particularly the Ananda Temple.

Kyanzittha was succeeded by Alaungsithu (1112-1167), the son of his daughter and of Sawluâs son, Sawyun. The new kingâs early years were spent repressing revolts, especially in Tenasserim and north Arakan. A Pali inscription found at Mergui is evidence that Tenasserim then paid allegiance to the Pagan monarchy. In north Arakan, a usurper had driven out the rightful heir, who had fled to Pagan, where he subsequently died. His son, with Alaungsithuâs assistance, recovered the inheritance. Alaungsithu traveled far and wide throughout his dominions building many works of merit; these pious pilgrimages form the main theme of the chronicles of his reign. His zeal for religion found its highest expression in the noble Thatpyinnyu Temple consecrated in 1144. It stands about 500 yards from the Ananda, and with its spite rising to a height of over zoo feet from the ground is the tallest of all the Pagan monuments. Its style is similar to that of the Ananda, but there is a much greater elevation of the mass before the tapering process begins, and the position of the main shrine is thus high above the ground.

By the mid-twelfth century, most of continental Southeast Asia was under the control of either the Pagan Kingdom or the Khmer Empire. Alaungsithu neglected the work of administration, and there was apparently much disorder during his long absences from the capital. In his old age Alaungsithu fell a victim to a court intrigue engineered by three of his sons. One of them, Narathu (r. 1167-1170), murdered his father and seized the throne. [6]His short reign was a time of disorder and bloodshed. The successor of the monk Shin Arahan, Panthagu, left the country in disgust and retired to Ceylon. In feverish atonement for his many cruelties, Narathu built the largest of all the Pagan temples, the Dammayan. Narathu was violently murdered.

His son Naratheinhka, who succeeded him, failed completely to deal with the anarchy which was widespread throughout the land, and was murdered by rebels in 1173. Then his younger brother, Narapatisithu, came to the throne, and during his reign of thirty-seven years (1173-1210) there is little record of disorder and much evidence of building.[7]

Under Kyanzittha and Alaungsithu, the Pagan had extended its dominion from the dry zone to incorporate Mon centers at Pegu and Thaton on the river delta. They established political and religious ties with Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). The royal court in the capital was supported by direct household taxes or service obligations drawn from the villages, which were under the direction of hereditary myothugis (âtownship headmenâ). As time passed, an increasing proportion of the land was donated to Buddhist monasteries in the form of slave villages for the maintenance of the sangha monastic community. The legitimacy of the rulers was supported by both Hindu ideology and the kingâs role as defender of the Buddhist faith.

End of Pagan Dynasty

The Pagan kingdom went into decline as more land and resources fell into the hands of the powerful sangha (monkhood) and the Mongols threatened from the north. The last true ruler of Pagan, Narathihapate (reigned 1254-1287) felt confident in his ability to resist the Mongols. In 1271, when Kublai Khan sent emissaries to regional powers of eastern Asia to demand tribute, Narathihapate refused the khan's representatives, and executed them on their second visit in 1273. When Kublai Khan did not immediately respond to this insult, Narathihapate gained confidence that the Mongols would not fight him. He subsequently invaded the state of Kaungai, whose chief had recently pledged fealty to Kublai Khan. Local garrisons of Mongol troops were ordered to defend the area, and although outnumbered, were able to soundly defeat the Pagan forces in battle and press into the Pagan territory of Bhamo. However, oppressive heat forced them to abandon their offensive and return to Chinese territory. In 1277, Narathihapate advanced into Yunnan to make war on the Mongol Yuan Dynasty. Mongol defenders soundly defeated the Pagan forces at the Battle of Ngasaunggyan.

The Battle of Ngassaunggyan was the first of three decisive battles between the two empires, the others being the Battle of Bhamo in 1283 and the Battle of Pagan in 1287. By the end of these battles, the Mongols had conquered the entire Pagan kingdom, where they installed a puppet government in 1289. This was the beginning of a turbulent period, during which the area of Upper Myanmar led an uncertain existence between Shan domination and tributary relations with China, while the area of Lower Myanmar reverted to Mon rule based at Pegu. Marco Polo later wrote a vivid report of the Battle of Ngasaunggyan. His description was presumably pieced together by accounts he heard while visiting the court of Kublai Khan.

Legacy

The people of the Pagan Kingdom made Buddhism their way of life while still retaining animistic and other unorthodox beliefs. The principles underlying religion, government, and society which were established during the Pagan Kingdom were accepted, almost without change, by later generations and dynasties of Myanmar.

City of Bagan

The prosperity and artistic glory of the Pagan Kingdom is attested by the temples and buildings of Bagan (Burmese: ááŻáá¶; MLCTS: pu. gam mrui.), formerly Pagan, formally titled Arimaddanapura (the City of the Enemy Crusher) and also known as Tambadipa (the Land of Copper) or Tassadessa (the Parched Land), located in the dry central plains, on the eastern bank of the Ayeyarwady River, 90 miles (145 km) southwest of Mandalay. Though he did not visit it, Marco Polo recorded the tales of its splendor that were recounted to him.

The ruins of Bagan cover an area of 16 square miles (40 km. sq.). The majority of its buildings were built in the 1000s to 1200s. It was founded 849 or 850 C.E. by legendary King Pyinbya as a small fortified town in an area overrun by Chinese legions, and became an important city when King Pyinbya moved the capital to Bagan in 874. However, in Burmese tradition, the capital shifted with each reign, and Bagan was once again abandoned until the reign of Anawrahta. The climate of the area permitted the cultivation of millet, ground nuts, palm trees and the breeding of cattle. Clay was available for making bricks, and teak for building could be floated down the rivers. The town square was situated between the Irawaddy and Chindwin Rivers, traditional routes north and south. The town was situated near an ancient road between India and Indochina, and only seven miles northwest of To-Wa, a range of hills that offered a strategic view across plains, so that approaching enemy forces could be seen well in advance. The original city center occupied an area of 1.5 sq km, and was surrounded by walls four meters thick and ten meters high. It is believed that the walls probably originally contained only royal, aristocratic, religious, and administrative buildings, while the populace lived outside in homes of light construction. [8]

In 1057, when King Anawrahta conquered the Mon capital of Thaton, he brought back the Tripitaka Pali scriptures, Buddhist monks and craftsmen, who helped to transform Bagan into a religious and cultural center. Mon monks and scholars taught the Burmans the Pali language and the Buddhist scriptures, and helped to make Bagan a center of Theravada Buddhism. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Bagan became a cosmopolitan center of Buddhist studies, attracting monks and students from as far as India, Sri Lanka as well as the Thai and Khmer kingdoms. Mon craftsmen, artisans, artists, architects, goldsmiths, and wood-carvers were captured at Thaton and taken to Pagan, where they taught their skills and arts to the Burmans. Inscriptions in the temples show that artisans were paid in wages of gold and silver, as well as in food, horses and elephants. Their clothing, shelter, health, comfort, and safety were the responsibility of their employers.

Hundreds of the estimated 3,000 to 4,000 temples and monasteries of Bagan are still standing. About 2,300 structures are registered by the Archaeological Survey; these are mostly stupas and temples, some as high as 70 meters, containing wonderful painting and sculpture from the twelfth through the eighteenth centuries. The buildings were principally constructed of brick, and decorated with carved brick, stucco, and terracotta. The earliest surviving structure is probably the tenth-century Nat Hlaung Gyaung. The shrines to traditional animist spirit deities, called nats, that stand by the Sarabha Gate in the eastern wall, although later than the wall they adjoin, are also early. [9]

Architectural Styles

The religious buildings of Bagan are often reminiscent of popular architectural styles in the period of their constructions. The most common types are:

- Stupa with a relic-shaped dome

- Stupa with tomb-shaped dome

- Sinhalese-styled stupa

- North Indian model

- Central Indian model

- South Indian model

- Mon model

Cultural Sites

- Ananda Temple, c. 1090, built by Kyanzittha

- Bupaya Pagoda, c. 850, demolished by the 1975 earthquake and completely rebuilt

- Dhammayangyi Temple, c. 1165, the largest temple in Bagan, built by Alaungsithu but never finished

- Dhammayazika Pagoda, 1196-1198, built by Narapatisithu (Sithu II)

- Gawdawpalin Temple, started by Narapatisithu and finished by Nandaungmya, the superstructure was destroyed by the 1975 quake and rebuilt

- Htilominlo Temple, 1218, built by Htilominlo

- Lawkananda Pagoda, built by Anawrahta

- Mahabodhi Temple, Bagan, c. 1218, a smaller replica of the temple in Bodh Gaya, India

- Manuha Temple, built by the captive Mon king Manuha

- Mingalazedi Pagoda, 1268-1274, built by Narathihapate

- Myazedi inscription, c. 1113, described as the "Rosetta Stone of Myanmar" with inscriptions in four languages: Pyu, Mon, Old Burmese and Pali, dedicated to Gubyaukgyi Temple by Prince Rajakumar, son of Kyanzittha

- Nanpaya Temple, c. 1060-1070, Mon style, believed to be either Manuha's old residence or built on the site

- Nathlaung Kyaung Temple, mid-eleventh century, Hindu deities "confined" to this temple

- Payathonzu Temple, probably around 1200

- Sein-nyet Ama & Nyima (temple and pagoda, thirteenth century)

- Shwegugyi Temple, 1131, built by Alaungsithu and where he died

- Shwesandaw Pagoda, c. 1070, built by Anawrahta

- Shwezigon Pagoda, 1102, built by Anawrahta, finished by Kyanzittha

- Sulamani Temple, 1183, built by Narapatisithu

- Tan-chi-daung Paya, on the west bank, built by Anawrahta

- Tharabha Gate, c. 850, built by King Pyinbya

- Thatbyinnyu Temple, the tallest temple at 200 feet (61 m), twe;fth century, built by Alaungsithu

- Tu-ywin-daung Paya, on the eastern boundary of Bagan, built by Anawrahta

Image Gallery

A Bagan Buddha, twelfth century

| Name | Relationship | Reign (C.E.) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thamudarit | 107-152 | founder of Bagan[10] | |

| Pyinbya | Son of Khelu | 846-878 | moved capital from Tampawadi (modern Pwasaw) to Bagan |

| Anawrahta | Son of Kunsaw Kyaunghpyu | 1044-1077 | founder of Bagan and the First Burmese Empire[11] |

| Sawlu | Son | 1077-1084 | |

| Kyanzittha | Brother | 1084-1113 | |

| Alaungsithu| Grandson | 1113-1167 | 1113-1160(?) | |

| Narathu | Son | 1167-1170 | 1160-1165(?), aka Kala-gya Min ( king fallen by Indians) |

| Naratheinkha | Son | 1170-1173 | |

| Narapatisithu | Brother | 1174-1211 | |

| Htilominlo | Son | 1211-1234 | aka Nandaungmya (one who often asked for the throne) |

| Kyaswa | Son | 1234-1250 | |

| Uzana | Son | 1250-1255 | |

| Narathihapati | Son | 1255-1287 | lost the kingdom to the Mongols and known as Tayoke Pyay Min (king who fled from the Chinese) to posterity |

| Kyawswa | Son | 1287-1298 | |

| Sawhnit | Son | 1298-1325 | |

| Sawmunnit | Son | 1325-1369 |

Notes

- â Pagan is the former English name for what is currently spelled Bagan. Many city names or spellings were changed by the Burmese government in 1989.

- â Pe Maung Tin and G. H. Luce, (translator) The Glass Palace Chronicle of the Kings of Burma. (Brooklyn, NY: AMS Press, (original 1923) 1976 in English)

- â Ibid.

- â Ibid.

- â D.G.E. Hall. Burma, Third edition, (1960), 18

- â Hall 1960, 21-22

- â Ibid., 22

- â U Kan Hla, "Pagan: Development and Town Planning," The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 36(1) (March 1977): 15-29 doi:10.2307/989143

- â Ibid.

- â Although Anawrahta is credited for the founding of Bagan, Thamudarit is the listed as the "traditional" founder of Bagan in The Glass Palace Chronicle (Hmannan Yazawin)

- â Idem.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, and Ian C. Glover. 1992. Southeast Asian archaeology 1990 proceedings of the Third Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists. Hull, UK: Centre for South-East Asian Studies. ISBN 085958593X

- Burma. 1979. Pictorial guide to Pagan. Rangoon: Ministry of Culture, Archaeology Dept., Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma.

- Ching, Frank, Mark Jarzombek, and Vikram Prakash. 2006. A Global history of architecture. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 0471268925

- Finger, Hans Wilhelm. 2004. Dhammayangyi the pyramid by the Irrawaddy: the biography of a temple, its people and the Kingdom of Pagan. Bangkok: Orchid Press. ISBN 9745240451

- Hudson, Bob, Nyein Lwin and Win Maung, U. "The Origins of Bagan: New Dates and Old Inhabitants." Asian Perspectives 40 (1) (Spring 2001): 48-74

- Pe Maung Tin and G. H. Luce, (translator) The Glass Palace Chronicle of the Kings of Burma. AMS Press (original 1923) 1976. (in English) ISBN 0404145558

- RanÊ»kunÊ» TakkasuilÊ», and TakkasuilÊ» myÄÊș Samuiáč Ê»Êș Sutesana áčŹhÄna (Rangoon, Burma). 1996. Glimpses of Glorious Bagan. Yangon, Myanmar: Universities Historical Research Centre.

- Strachan, Paul. 1989. Pagan art & architecture of old Burma. Whiting Bay, Arran [Scotland]: Kiscadale. ISBN 9781870838207

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- Bagan Map. DPS Online Maps.

- The Life of the Buddha in 80 Scenes, Ananda Temple Charles Duroiselle, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report, Delhi, 1913-14.

- The Art and Culture of Burma - the Pagan Period Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Northern Illinois University.

- Temples of Bagan Photo Gallery Alan Ingram.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Pagan_Kingdom history

- Anawrahta history

- Sawlu history

- Kyanzittha history

- Alaungsithu history

- Narathihapate history

- Battle_of_Ngasaunggyan history

- Glass_Palace_Chronicle history

- Bagan history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.