Jeju Uprising

The Jeju Uprising or Jeju Massacre (old spelling, "Cheju") refers to the rebellion and subsequent heavy government suppression on Jeju Island, South Korea, beginning April 3, 1948. In Jeju, it is referred to as the "4.3 Uprising" or "4.3 Massacre" (4.3 referring to April 3); between 30,000 and 60,000 people were killed in fighting between factions. Suppression of the rebellion by the South Korean army was brutal, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths, destroying many villages on the island, and sparking rebellions on the Korean mainland. The rebellion included the mutiny of several hundred members of the South Korean 11th Constabulary Regiment and lasted until May 1949, although small isolated pockets of fighting continued during the Korean War into 1953.[1]

Background

The detested Japanese occupation of Korea, which began in 1910, finally ended with Japan's defeat in World War II on August 15, 1945. American and Soviet troops arrived to accept the Japanese surrender in southern and northern parts of the Korean Peninsula, respectively. American and Soviet armies stayed separated at the 38th Parallel by a prearranged agreement between United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin.

In the post-WWII years, the three major nations of the Far East‚ÄĒChina, Korea and Japan‚ÄĒall struggled with the rise of Communism; in China, the Maoists won and established a Communist government, in Japan the communist Red Guards were suppressed, in Korea a massive war was fought and the country was divided. The region eventually coalesced into free and Communist blocs in the process of the Cold War, but beforehand the two ideologies were not so clearly separated and fierce ideological, sometimes physical, fighting took place in cities, villages, and countryside. Jeju was no exception, except that the fight turned exceptionally bloody.

Jeju's isolation had always meant the Seoul government was a distant influence compared to other areas of Korea. Prevailing sentiment on Jeju was that the local government and police forces were made up mostly of those who had readily collaborated with the Japanese occupation, and there was unrest at heavy taxation of agricultural and fishing commodities reminiscent of the Joseon Dynasty.[2] Many of the Jeju people were more inspired by their perception of a future promoted by Kim Il Sung in North Korea than by the capitalist version taking shape in South Korea, and in Japan.

Elections called

On November 14, 1947, the United Nations passed UN Resolution 112, calling for a general election over the whole Korean peninsula under the supervision of a UN commission. However, the Soviet Union, occupying the northern part of the peninsula, refused to comply with the UN resolution and denied the UN Commission access. The UN Assembly adopted a new resolution calling for elections in areas accessible to the UN Commission, which at that time included only members of the United States Army Military Government in Korea, also known as USMAGIK.

The rebellion

Upset by the partition of the peninsula, the communist South Korean Workers' Party leaders planned rallies all over South Korea on March 1, to denounce and block the upcoming general elections scheduled for May 10. The arrest of 2,500 party cadres on Jeju and the killing of at least three of them broke up the planned demonstrations. On April 3, 1948, rebels attacked eleven police stations, mutilating those found inside, and burned polling centers for the upcoming election. They also attacked political opponents and their families, and issued an appeal urging the local population to rise up and liberate their country from the ‚ÄúAmerican cannibals and their running dogs.‚ÄĚ

Seeking a speedy resolution to the insurrection, the South Korean government sent 3,000 soldiers of the South Korean 11th Constabulary Regiment to reinforce local police, but on April 29, several hundred soldiers mutinied, handing over large small-arms caches to the rebels. The Seoul government also sent several hundred Northwest Youth Association members, a group of anti-communist North Korean refugees as part of a paramilitary force. These men were considered by locals as right-wing thugs.

Lt. General Kim Ik Ruhl, commander of the South Korean force on the island, attempted to end the insurrection peacefully by negotiating with the rebels. He met several times with rebel leader Kim Sam-dal but they could not reach any agreement. The government wanted what amounted to a complete surrender, and the rebels demanded disarmament of the local police, dismissal of all governing officials on the island, prohibition of paramilitary groups on the island and reunification of the Korean peninsula. General Kim Ik Ruhl was suddenly recalled to Seoul over his conciliatory approach with the rebels and was surprised when his replacement mounted a fierce and sustained offensive against the rebels.

The guerrillas created base camps on Mt. Hallasan and the government forces held the coastal towns. Farming communities between the coast and the heights became the primary battle-zone. By October 1948, the rebel army consisted of approximately 4,000 combatants, and although most were poorly armed they scored several minor victories over the Army. In late fall of 1948, the rebels began openly siding with Kim Il Sung by flying North Korean flags.[3]

By spring of 1949, however, four Korean army battalions arrived and joined the local constabulary, police forces and Youth Association partisans. The combined forces quickly finished off most of the remaining rebel forces. On August 17, 1949, the rebel leadership of the movement following the killing of major rebel leader Yi Tuk-ku.

Reporters from Stars and Stripes, published by the U.S. Army provided vivid and uncensored accounts of the South Korean Army’s brutal suppression of the rebellion, the local popular support of the rebels, as well as the rebels' retaliation against government forces.

The massacre

Immediately after North Korea invaded the South across the 38th Parallel on June 25, 1950, the South Korean military ordered "preemptive apprehension" of suspected leftists nationwide. Thousands were detained on Jeju, then sorted into four groups, labeled A, B, C, and D, based on the security risks each was perceived to pose. On August 30, 1950, according to a written order by a senior intelligence officer in the South Korean Navy, the Jeju police were instructed to "execute all those in groups C and D by firing squad no later than September 6."[4]

South Korea's Truth Commission reported 14,373 victims, 86 percent at the hands of the security forces and 13.9 percent at the hands of armed rebels, and estimated that the total death toll was as high as 30,000.[5] The Koreans committed these atrocities in front of the U.S. military. The Americans documented the massacre, but never intervened.

Aftermath

In March of 1950, North Korea sent thousands of armed insurgents to resuscitate the guerrilla fighting on Jeju, but by this time the South Korean army had become particularly adept at counterinsurgency and quashed the new uprising in only a few weeks. In one of its first official acts, the South Korean national assembly passed the National Traitors Act in 1948, which among other measures, outlawed the South Korean Labor Party.[6]

Many residents of Jeju escaped to Japan, some establishing a Jeju town in Osaka. At many locations around Jeju, the sites where citizens were killed have been marked with simple towers of volcanic stones. Others have been recognized more formally, with grave markers and memorial stone monuments.

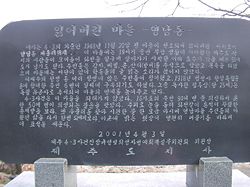

Translation of the text of the stone monument to Yeongnam Village (pictured above), one of many villages destroyed during the Jeju Uprising:

- The lost village‚ÄĒYeongnamdong‚ÄĒ

- This is the former location of Yeongnamdong village, Seoguipo, which was burned to the ground about November 20, 1948, during the whirlwind of the Jeju Uprising.

- In mid nineteenth century Jeju where life was difficult, this was a village where farmers worked the land they had cleared. At its peak, Yeongnamdong was home to more than 50 families. The villagers raised potatoes, buckwheat, beans and dry-field rice and raised livestock. The sound of students reciting verses could always be heard from the village had a Seodang (school).

- Villagers participated in resistance activities, and six members of the village were arrested for their participation in anti-Japanese protests in 1918. Among them Dusan Kim, who died in prison at the age of 25, was awarded an independence medal, bringing distinction to the village.

- The 50 members of 16 households who did not flee the village during the Jeju Uprising had the misfortune of perishing in the fire that destroyed the village. If you look around, you can see traces of the fields where the villagers farmed. Find the village well, and take a cool drink and remember the life of Yeongnam Village. This stone monument is erected with a wish that bright sunlight will always shine on Yeongnam Village.

- April 3, 2001

- Governor of Jejudo

- Chairman of the committee for investigating and compensating the victims of the Jeju Uprising

The massacre was largely ignored by the Korean government for many years. In 1992, South Korean President Roh Tae Woo's government sealed up a cave on Mount Halla, where the remains of massacre victims had been discovered. But after civilian rule was reinstated later in the 1990s, the government made several cases of apologies for the suppression, and efforts are being made to re-assess the scope of the incident and compensate the survivors. In April 2006, President Roh Moo-hyun officially apologized to the people of Jeju Province for the 4.3 Massacre, and announced that the government had granted the long-held wishes of Jeju's people to gain administrative autonomy. Jeju is now Jeju Special Self-Governing Province.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ John Kie-Chiang Oh, Korean Politics: The Quest for Democratization and Economic Development (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999, ISBN 0801434475).

- ‚ÜĎ Michael Breen, The Koreans: America's Troubled Relations with North and South Korea (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 1999, ISBN 0312242115).

- ‚ÜĎ Michael J. Varhola, Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950‚Äď1953 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Woodbury Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1882810430).

- ‚ÜĎ George Wehrfritz, B.J. Lee, Hideko Takayama, Ghosts of Cheju, Newsweek. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ The National Committee for the Truth About the Jeju April 3 Incident, Truth-Finding Efforts and Recommendations. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Carter Malkasian, The Korean War (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2001, ISBN 1841762822).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cumings, Bruce. 1997. Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393040111.

- Hyun, Kil-Un. 2007. Dead Silence: Stories on the Jeju Massacre. [S.l.]: Eastbridge.

- Merrill, John. 1989. Korea: The Peninsular Origins of the War. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 9780874133004.

External links

All links retrieved December 23, 2024.

- The Korea Times: Conservatives Downgrade Jeju Uprising in 1948.

- Wehrfritz, George, B.J. Lee, Hideko Takayama. 2000. Ghosts of Cheju. Newsweek.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.