Chameleon

| Chameleon | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Bradypodion |

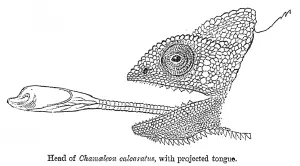

Chameleon is any of the tropical, New World lizards comprising the family Chamaeleonidae, known primarily for their ability to change body color. Chameleons are characterized by very long tongues, bulged eyes that can rotate and focus separately, joined upper and lower eyelids (with a pinhole for viewing), lack of an outer or middle ear (unlike most lizards, but like snakes), and with the five toes on each foot fused into opposite groups of two and three.

Small- to medium-sized squamates, which are primarily tree-dwelling, chameleons are found mainly in sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar, although some species exist in southern Europe, South Asia, and Australia, with feral populations elsewhere. The common chameleon, Chamaeleo chamaeleon, lives in the Mediterranean area.

Chameleon's add to the human wonder of nature, given their ability to change color. However, the mechanism and reason that chameleons change color has often been misunderstood. Although it is popularly believed that they change based on their surrounding background, this has been scientifically discounted; rather, color change is tied to other environmental factors (intensity of external light), physiological factors (whether overly warm or cool, illness, gravidity), and emotional conditions (stress (medicine), fear, discontentment, presence of other animals) (Anderson 2004).

The color-changing "American chameleon," Anolis carolinensis, also known as the Carolina or green anole, is not a true chameleon, belonging to the family Polychrotidae (or the subfamily Polychrotinae of the iguana family, Iguanidae).

The name "chameleon" means "earth lion" and is derived from the Greek words chamai (on the ground, on the earth) and leon (lion).

Description

Chameleons vary greatly in size and body structure, with total length from approximately one inch (two centimeters) in Brookesia minima, to the 31 inches (79 centimeters) in male Furcifer oustaleti (Glaw and Vences 1994). Many have head or facial ornamentation, be it nasal protrusions or even horn-like projections in the case of Chamaeleo jacksonii, or large crests on top of their head, like Chamaeleo calyptratus. Many species are sexually dimorphic, and males are typically much more ornamented than the female chameleons.

The main things chameleon species have in common is their foot structure, their eyes, their lack of ears, and their tongue.

Chameleons are zygodactyl: on each foot, the five toes are fused into a group of two digits and a group of three digits, giving the foot a tongs-like appearance. These specialized feet allow chameleons to grip tightly to narrow branches. Each toe is equipped with a sharp claw to gain traction on surfaces such as bark when climbing. The claws make it easy to see how many toes are fused into each part of the foot: two toes on the outside of each front foot and three on the inside, and the reverse pattern on each hind foot.

Their eyes are the most distinctive among the reptiles. The upper and lower eyelids are joined, with only a pinhole large enough for the pupil to see through. They can rotate and focus separately to observe two different objects simultaneously. It in effect gives them a full 360-degree arc of vision around their body. When prey is located, both eyes can be focused in the same direction, giving sharp stereoscopic vision and depth perception.

Chameleons lack a vomeronasal organ (auxiliary olfactory sense organ in some tetrapods, such as snakes). Also, like snakes, they lack an outer or a middle ear. This suggests that chameleons might be deaf, although it should be noted that snakes can hear using a bone called the quadrate to transmit sound to the inner ear. Furthermore, some or maybe all chameleons, can communicate via vibrations that travel through solid material like branches.

Chameleons have incredibly long, prehensile tongues (sometimes longer than their own body length), which they are capable of rapidly and abruptly extending out of the mouth. The tongue whips out faster than our eyes can follow, speeding at 26 body lengths per second. The tongue hits the prey in about 30 thousandths of a second‚ÄĒone tenth of an eye blink (Holladay 2007). The tongue has a sticky tip on the end, which serves to catch prey items that they would otherwise never be able to reach with their lack of locomotive speed. The tongue's tip is a bulbous ball of muscle, and as it hits its prey, it rapidly forms a small suction cup. Once the tongue sticks to a prey item, it is drawn quickly back into the mouth, where the chameleon's strong jaws crush it and it is consumed. Even a small chameleon is capable of eating a large locust or mantis.

Ultraviolet light is actually part of the visible spectrum for chameleons. Primarily, this wavelength affects the way a chameleon perceives its environment and the resultant physiological effects. Chameleons exposed to ultraviolet light show increased social behavior and activity levels, are more inclined to bask and feed and are also more likely to reproduce as it has a positive effect on the pineal gland.

Distribution and habitat

The main distribution of Chameleons is Africa and Madagascar, and other tropical regions, although some species are also found in parts of southern Europe, Asia, and Australia. Madagascar has the greatest diversity, with about half of all species located there. There are introduced, feral populations of veiled and Jackson's chameleons in Hawaii and isolated pockets of feral Jackson's chameleons have been reported in California and Florida.

Different members of this family inhabit all kinds of tropical and montane rain forests, savannas, and sometimes semi-deserts and steppes. Chameleons are mostly arboreal and are often found in trees or occasionally on smaller bushes. Some smaller species, however, live on the ground under foliage.

Reproduction

Chameleons are mostly oviparous (egg laying, with little or no other embryonic development within the mother), with some being ovoviviparous (young develop within eggs that remain within the mother's body up until they hatch or are about to hatch).

The oviparous species lay eggs after a three to six week gestation period. Once the eggs are ready to be laid, the female will climb down to the ground and begin digging a hole, anywhere from four to 12  inches (ten to 30 centimeters) deep depending on the species. The female turns herself around at the bottom of the hole and deposits her eggs. Once finished, the female buries the eggs and leaves the nesting site. Clutch sizes vary greatly with species. Small Brookesia species may only lay two to four eggs, while large veiled chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus) have been known to lay clutches of 80-100 eggs. Clutch sizes can also vary greatly among the same species. Eggs generally hatch after four to 12 months, again depending on species. The eggs of Parson's Chameleon (Calumma parsonii), a species which is rare in captivity, are believed to take upwards of 24 months to hatch.

The ovoviviparous species, such as Jackson's chameleon (Chamaeleo jacksonii) and the flapjack chameleon (Chamaeleo fuelleborni), give birth to live young after a gestation of four to six months, depending on the species.

Feeding habits

Chameleons generally eat locusts, mantids, crickets, grasshoppers, and other insects, but larger chameleons have been known to eat small birds and other lizards. A few species, such as Chamaeleo calyptratus, have been known to consume small amounts of plant matter. Chameleons prefer running water to still water.

It was commonly believed in the past that the chameleon lived on air, and did not consume any food at all. This belief is today represented in symbolic form, with the chameleon often being used as a motif to signify air.

Change of color

The ability of some chameleon species to change their skin color has made Chamaeleonidae one of the most famous lizard families. While color change is one of the most recognized traits of chameleons, commented on scientifically since Aristotle, it also is one of the most misunderstood features of these lizards (Anderson 2004). Changing color is an expression of the physical, physiological and emotional conditions of the chameleon (Harris 2007), tied to causes such as intensity of external light, stress, illness, fear (as postulated by Aristotle), discontentment, and being overly cool or overly warm, among other causes (Anderson 2004). The color also plays an important part in communication.

Despite popular belief, chameleons do not change color to match their surroundings (Anderson 2004). Chameleons are naturally colored for their surroundings as a camouflage.

How chameleon's change color is tied to specialized cells, collectively called chromatophores, that lie in layers under their transparent outer skin. The cells in the upper layer, called xanthophores and erythrophores, contain yellow and red pigments respectively. Below these is another layer of cells called iridophores or guanophores, and they contain the colorless crystalline substance guanine. These reflect, among others, the blue part of incident light. If the upper layer of chromatophores appears mainly yellow, the reflected light becomes green (blue plus yellow). A layer of dark melanin containing melanophores is situated even deeper under the reflective iridophores. The melanophores influence the "lightness" of the reflected light. All these different pigment cells can rapidly relocate their pigments, thereby influencing the color of the chameleon. The external coloration changes with the different concentrations of each pigment, with the chromatophores synchronized by neurological and hormonal control mechanism responsive to central nervous system stimuli (Anderson 2004).

Pets

Numerous species of chameleon are available in the exotic pet trade. Jackson's chameleon (Chamaeleo jacksonii) and veiled chameleon (C. calyptratus) are by far the most common in captivity. Most species of chameleons are listed on CITES, and therefore are either banned from exportation from their native countries or have strict quotas placed on the numbers exported. However, lack of enforcement in what are mostly poor countries reduces the effectiveness of this listing. Captively bred animals of the most popular species (panther, veiled, and Jackson's) are readily found.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, C. 2004. Color chameleon mechanism in chameleons ChameleonNews.

- Glaw, F., and M. Vences. 1994. A Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of Madagascar, 2nd edition. Köln, Germany: M. Vences and F. Glaw Verlags. ISBN 3929449013.

- Harris, T. 2007. How animal camouflage works How Stuff Works. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- Holladay, A. 2007. A lethal lashing tongue Wonderquest. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.