Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (German: Skagerrakschlacht (Battle of the Skagerrak); Danish: Søslaget ved Jylland / Søslaget om Skagerrak) was the largest naval battle of World War I and the only full-scale clash of battleships in that war. It was fought on May 31-June 1, 1916, in the North Sea near Jutland, the northward-pointing peninsular mainland of Denmark. The combatants were the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer and the Royal Navy’s British Grand Fleet commanded by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. The intention of the German fleet was to lure out, trap and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, as the Germans were insufficient in number to engage the entire British fleet at one time. This formed part of their larger strategy of breaking the British naval blockade of the North Sea and allowing German mercantile shipping to operate again. The Royal Navy, on the other hand, was pursuing a strategy seeking to engage and cripple the High Seas Fleet and keep the German force bottled up and away from their own shipping lanes.

Fourteen British and eleven German ships were sunk with great loss of life. After sunset, and throughout the night, Jellicoe maneuvered to cut the Germans off from their base in hopes of continuing the battle in the morning, but under cover of darkness Scheer crossed the wake of the British fleet and returned to port. Both sides claimed victory. The British had lost more ships and many more sailors, and the British press criticized the Grand Fleet's actions, but Scheer’s plan of destroying Beatty’s squadrons had also failed. The Germans continued to pose a threat that required the British to keep their battleships concentrated in the North Sea, but they never again contested control of the seas. Instead, the German Navy turned its efforts and resources to unrestricted submarine warfare.

Background

German planning

The German High Seas Fleet had only eighteen battleships and were falling increasingly further behind as the war progressed. Since the British Grand Fleet had thirty-three, there was little chance of defeating the British in a head-to-head clash of battleships. Instead, the German strategy was to divide and conquer: By staging raids into the North Sea and bombarding the English coast, they hoped to lure out small British squadrons and pickets which could then be attacked and destroyed by superior forces or submarines. The German naval strategy, according to Scheer, was:

To damage the English Fleet by offensive raids against the naval forces engaged in watching and blockading the German Bight, as well as by mine-laying on the British coast and submarine attack, whenever possible. After an equality of strength had been realized as a result of these operations, and all our forces had been made ready and concentrated, an attempt was to be made with our fleet to seek battle under circumstances unfavorable to the enemy.

The plan for May 1916, was to station a large number of U-boats off the British naval bases and lure Beatty's battlecruiser squadrons out by sending a fast cruiser fleet under Hipper to raid the coast of Sunderland. If all went well, after the British sortied in response to the raiding attack force, the British squadrons would be weakened by the picketing submarine ambush, and the British Navy's centuries-long tradition of aggressive command could be used to draw those pursuing but weakened units after Hipper's cruisers towards the German dreadnoughts positioned in a high seas ambush under Scheer and destroyed.

It was further hoped once a submarine attacked successfully, that fast escorts such as destroyers, the scouting eyes of the main fleets, would be tied down conducting anti-submarine operations against that line, and effectively hold the larger British units off shore against the submarine force between it and its ports. The German planning thus had several strings to their bow, and had they caught the British in the positions where they expected them to be, they had a good chance to alter their numerical imbalance by inflicting serious damage on the scattered British forces.

Unfortunately for the German planning, the British had gained possession of the main German code books (the British had been given a German code book from the light cruiser SMS Magdeburg, boarded by Russian naval officers after the ship ran aground in Russian territorial waters) so intercepted German naval radio communications could usually be deciphered, and hence the British Admiralty was therefore usually aware of German deployments and activity levels, giving them a glimpse into the German plans and the ability to formulate better responses from this extra military intelligence.

British response

The British intercepted and decrypted a German signal on May 28 ordering all ships to be ready for sea on May 30. Further signals were intercepted and although they were not decrypted it was clear that a major operation was likely.[1]

Not knowing the Germans objective, Jellicoe and his staff decided to position the fleet to head off any attempt by the Germans to enter the North Atlantic or Baltic through the Skagerrak by taking up a position off Norway where they could possibly cut off any German raid into the shipping lanes of the Atlantic, or prevent the Germans from heading into the Baltic. A position further west was unnecessary as that area of the North Sea could be patrolled by air using Blimps and scouting aircraft.[2]

Consequently, Admiral Jellicoe led the Grand Fleet of twenty-four dreadnoughts and three battlecruisers east out of Scapa Flow before Hipper's raiding force left the Jade Estuary on May 30 and the German High Seas Fleet could follow. Beatty's faster force of four dreadnoughts and six battlecruisers left the Firth of Forth on the next day, and Jellicoe's intention was to rendezvous 90 miles (145 kilometers) west of the mouth of Skagerrak off the coast of Jutland and wait for the Germans or for their intentions to become clear. The planned position gave him the widest range of responses to likely German intentions.[3]

Orders of battle

Jellicoe's battle force was twenty-eight dreadnoughts and nine battlecruisers, while Scheer had sixteen dreadnoughts, five battlecruisers and six obsolete pre-dreadnoughts. The British were superior in light vessels as well. Due to a preference of protection over firepower in the German ship-designs the German ships had thicker armor against shellfire attack, but carried fewer or smaller guns than their British counterparts. No German ship participating in the battle was equipped with guns larger than 12 inch (305 mm) while most British capital ships had 13.5 inch (343 mm) or 15 inch (381 mm) guns. Combined with their larger number this gave the British an advantage of 332,400 lb (151 metric tons) against 134,000 lb (61 metric tons) in terms of weight of broadside.

The German ships had better internal sub-division as they were only designed for short cruises in the North Sea and their crews lived in barracks ashore when in harbor; therefore they didn't need to be as habitable as the British vessels, and had fewer doors and other weak points in their bulkheads. German armor-piercing shells were far more effective than the British shells; and, vitally important, the British cordite propellant tended to blow up their ships when hit by incoming shellfire rather than "burn" as in German ships, and the British magazines were not well protected. Furthermore, the German Zeiss optical equipment (for range-finding) was superior. On the other hand the British fire control systems were well in advance of the German ones, as demonstrated by the proportion of main caliber hits under manœuvre.

Concentration of force at one point and communications dictated the tactics used in fleet actions when the large rifled naval guns now in use could literally shoot beyond the horizon. Thus tactics called for a fleet approaching battle to be in parallel columns moving in-line ahead, allowing both relatively easy manœuvring and shortened sight lines for command and control communications. Also, several short columns could change their heading faster than a single long column while maintaining formation, and if a column were too long, trailing units may never reach an effective range to fire at an enemy unit. Since coordinating command and control signals in the era were limited to visible means—made with flags or shuttered searchlights between ships—the flagship was usually placed at the head of the centre column so orders could be seen by the many ships of the formations.

Also, since coal fired boilers of the era generated a lot of smoke from the funnels, the trailing clouds of smoke often made it impossible to identify signals on ships beyond the one directly ahead or behind, so every ship had to repeat the signal for the following one to understand. The time required for this was often doubled as most signals had to be confirmed by every ship before they could be executed and passed on. In a large single-column formation a signal could take 10 minutes or more to be passed from the flagship at the front of the column to the last ship at the end, whereas in a columns formation moving line-ahead, visibility across the diagonals was often better (and always shorter) than a single long column, and the diagonals gave signal redundancy increasing the chance that a signal would been seen and correctly interpreted sooner.

For the actual battle the fleet would deploy into a single column by the leading ships of the columns turning 90 degrees to port or starboard, the remaining ships following their leaders in succession, the column being formed at right angles to the original line of advance. To form the column into the right direction the fleet had to know from which direction the enemy was approaching before he could be seen by the enemy battleships, as this manœuvre took longer to achieve than two fleets heading towards each other at high speed needed to come within fighting range. It was the task of the scouting forces, consisting of battlecruisers and cruisers, to find the enemy and report his position, course and speed with sufficient time and, if possible, deny the enemy's scouting force the opportunity of obtaining the same information.

Ideally the line of battleships would cross the path of the enemy column so that the maximum number of guns could be brought to bear, while the enemy could only fire with the front turrets of the leading ships. Carrying out this classic maneuver of "crossing the T" was largely a matter of luck; more common were heavy exchanges between two fleets on roughly parallel courses.

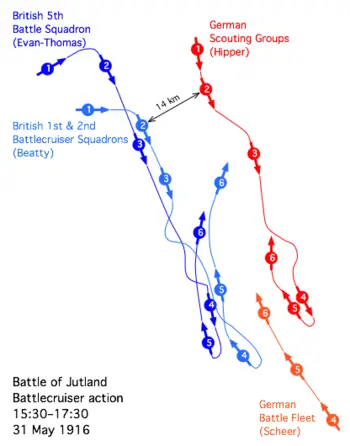

Battlecruiser action

(2) 15:45 hrs, First Shots fired by Hipper's squadron.

(3) 16:00 hrs-16:05 hrs, Indefatigable explodes leaving two survivors.

(4) 16:25 hrs, Queen Mary disintegrates, nine survive.

(5) 16:45 hrs, Beatty's Battlecruisers escape the action.

(6) 16:55 hrs, Evan-Thomas' Battleships run the gauntlet.

Prelude to big guns

The German U-boats were completely ineffective; they did not sink a single ship and provided no useful information as scouts. Jellicoe's ships proceeded to his rendezvous undamaged but misled by Admiralty intelligence that the Germans were nine hours later than they actually were.

At 2:20 p.m. on May 31, despite heavy haze and scuds of fog giving poor visibility, scouts from Beatty's force reported enemy ships to the south-east; the British light units, investigating a neutral Danish steamer which was sailing between the two fleets, had also found German scouts engaged in the same mission. Beatty moved eastwards to cut the German ships off from their base. The first shots of the battle were fired when Galatea of the British 1st Light Cruiser Squadron mistook two German destroyers for cruisers and engaged them. Galatea was subsequently hit at extreme range by her German counterpart, Elbing, of Rear Admiral Bodicker's Scouting Group II.[4]

At 3:30 p.m., Beatty's forces sighted Hipper's cruisers moving south-east (position 1 on map). Hipper promptly turned away to lead Beatty towards Scheer. Beatty, some three miles (5 km) from Rear-Admiral Sir Hugh Evan-Thomas's column (5th Battle Squadron), turned towards the enemy and signaled by flag for the 5th Battle Squadron to follow.[5]

The run to the south

Given the distance and visibility, the 5th could not read the flag signals; and as Beatty made no effort to communicate via searchlight or radio telegraph, the 5th continued on its original course for several minutes. During the next quarter hour, Beatty's actions receive a lot of criticism as his ships out-ranged and outnumbered the German squadron, yet he held his fire. At 3:45 p.m., after having the German ships within range for over ten minutes, and with both fleets roughly parallel at 15,000 nautical-yards (14 km (8.7 mi)), Hipper opened fire followed by Beatty (position 2). Thus began the opening phase of the fleet action, known as the "Run to the South." During the first long minutes of the ensuing action, all the British ships fired well over the German fleet, before finally getting the range.[6]

Beatty had ordered his ships to engage in a line, one British ship engaging with one German and his flagship Lion doubling on the German flagship Lützow. However, due to another mistake on the British part, Derfflinger was left unengaged and free to fire without disruption, while Moltke drew fire from two battlecruisers. The Germans drew first blood. Hipper's five battlecruisers promptly registered hits on three of the six British battlecruisers. Nearly ten minutes passed before the British managed to score their first hit. Naval forensic historians estimate the Germans scored 35 hits to 11 in the next interval.[7]

Sudden death

The first near-disaster of the battle occurred when a 12 inch (305 mm) salvo from Lützow wrecked "Q" turret of Beatty's flagship Lion. Dozens of crewmen were instantly killed, but a far larger catastrophe was averted when the mortally wounded turret commander, Major Francis Harvey of the Royal Marines, promptly ordered the magazine doors shut and the magazine flooded, thereby preventing the fickle propellant from setting off a massive magazine explosion. Lion was saved. Indefatigable was not so lucky; at 4:00 p.m., just fifteen minutes into the slugging match, she was smashed aft by three 11 inch (280 mm) shells from Von der Tann, causing damage sufficient to knock her out of line and drop her speed significantly. Soon after, despite the near-maximum range, Von der Tann put another 11-inch (280 mm) salvo on one of her 12-inch (305 mm) turrets. The plunging shells easily pierced the thin upper armor and Indefatigable was ripped apart by a magazine explosion, sinking immediately with her crew of 1,019 officers and men, leaving only two survivors (position 3).[8]

That tipped the odds to Hipper's benefit, for a brief while as Admiral Evan-Thomas, essentially chasing from oblique (astern) finally manœuvered his squadron of four fast "super-dreadnoughts" into long range. He commanded a squadron of the Queen Elizabeth class armed with 15 inch (381 mm) guns. With occasional 15-inch (381 mm) shells landing on his ships at long ranges, Hipper was in a tight spot and unable to respond at all against Evan-Thomas's squadron with his smaller shorter-ranged guns, but had his hands full with Beatty's units. He also knew his baiting mission was close to completion and his force was rapidly closing Scheer's main body and had little choice as there was little speed difference between the sides engaged. At 4:25 pm the battlecruiser action intensified again when Queen Mary was hit by what may have been a combined salvo from Derfflinger and Seydlitz, and she disintegrated in a magazine explosion with all but 20 of her 1,266 man crew lost.[9]

Off to the side

Shortly after, a salvo struck on or about Princess Royal, which was obscured by spray and smoke.[10] A signalman leaped to the bridge of Lion, "Princess Royal's blown up, Sir." Beatty famously turned to his flag captain, "Chatfield, there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today. Turn two-points to port," that is, two points nearer the enemy (position 4). However, the signalman's report was incorrect, as Princess Royal survived the battle.

At about 4:30 p.m., Southampton of Beatty's 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron led by Commodore William Goodenough sighted the main body of Scheer's High Seas Fleet, dodging numerous heavy-caliber salvos to report the detailed strength of the Germans: sixteen dreadnoughts with six older battleships. Simultaneously a destroyer action raged between the battlecruiser fleets, as British destroyers scrapped with their German counterparts and managed to put a torpedo into Seydlitz. The destroyer Nestor, under the command of Captain Bingham, sank two German torpedo boats, V 27 and V 29, before she and another destroyer, Nomad, were immobilized by hits and later sunk by Scheer's dreadnoughts.[11]

The run to the north

Beatty headed north to draw the Germans towards Jellicoe and managed to break contact with the Germans at about 4:45 pm (position 5). Beatty's move towards Jellicoe is called the "Run to the North." Because Beatty once again failed to signal his intentions adequately, the super-dreadnoughts of the 5th Battle Squadron found themselves lagging behind the battlecruisers and heading directly into the main body of the High Seas Fleet.

Their difficulty was compounded by Beatty, who gave the order to Evan-Thomas to "turn in succession" rather than "turn together." There is poorly-referenced speculation that the exact wording of the order originated with Lieutenant-Commander Ralph Seymour, Beatty's flag lieutenant, rather than Beatty himself. This should have resulted in all four ships turning, in succession to transit through the same patch of sea, which gave the High Seas Fleet repeated opportunity with ample time to find the proper range. Consequently, the trailing ships experienced a period wherein they had to fend off the lead German dreadnoughts and Hipper's battlecruisers on their own. Fortunately, the dreadnoughts were far better suited to take this sort of pounding than the battlecruisers, and none were lost, as in the event, one captain turned early mitigating the adverse results. Nonetheless, Malaya sustained heavy casualties in the process, likely lessened by the initiative of her Captain in turning early. At the same time, the 15 inch (381 mm) fire of the four British ships remained effective, causing severe damage to the German battlecruisers (position 6).[12]

Still fighting blind

Jellicoe was now aware that full fleet engagement was nearing, but had insufficient information on the position and course of the Germans. Rear Admiral Horace Hood's 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron was ordered to speed ahead to assist Beatty, while Rear-Admiral Arbuthnot's 1st Cruiser Squadron patrolled the van of the main body for eventual deployment of Jellicoe's dreadnought columns.

Around 5:30 p.m. the cruiser Black Prince of Arbuthnot's squadron, bearing southeast, came within view of Beatty's leading 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron, establishing the first visual link between the converging bodies of the Grand Fleet. Simultaneously the signals cruiser Chester, steaming behind Hood's battlecruisers, was intercepted by the van of the German scouting forces under Rear-Admiral Bodicker.[13]

Heavily outnumbered by Bodicker's four light cruisers, Chester was pounded before being relieved by Hood's heavy units which swung back westward for that purpose. Hood's flagship Invincible disabled the light cruiser Wiesbaden as Bodicker's other ships fled toward Hipper and Scheer, in the mistaken belief that Hood was leading a larger force of British capital ships from the north and east. Another destroyer action ensued as German torpedo boats attempted to blunt the arrival of this new formation.[14]

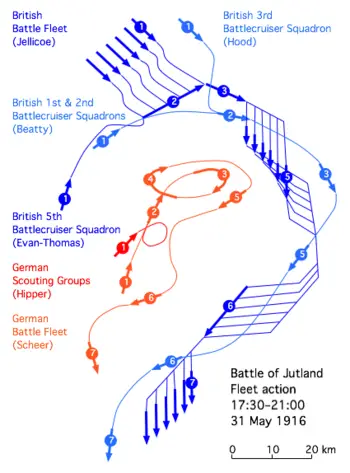

The fleet action

In the meantime Beatty and Evan-Thomas had resumed their engagement of Hipper's battlecruisers, this time with the visual conditions to their advantage. With several of his ships damaged, Hipper turned back to Scheer around 6:00 p.m., just as Beatty's flagship Lion was finally spotted by Jellicoe on Iron Duke. Jellicoe promptly demanded the latest position of the German forces from Beatty, who failed to respond to the question for almost ten minutes.[15]

Jellicoe, having overestimated the enemy forces, was in a worrying position, needing to know the position of the Germans in order to judge when and how to deploy his battleships from their cruising formation in column into a single battle line. The deployment could be onto either the western or the eastern column and had to be carried out before the Germans arrived; but early deployment could mean losing any chance of a decisive encounter. Deploying to the west would bring his fleet closer to Scheer, gaining valuable time as dusk approached, but the Germans might arrive before the manœuvre was complete. Deploying to the east would take the force away from Scheer, but Jellicoe's ships might be able to cross the "T" and would have the advantage of silhouetting Scheer's forces against the setting sun to the west. Deployment would take twenty irreplaceable minutes, and the fleets were closing at speed. Jellicoe ordered deployment to the east at 6:10 p.m.[16]

Meanwhile Hipper had rejoined Scheer, and the combined High Seas Fleet was heading north, directly toward Jellicoe. Scheer had no indication that Jellicoe was at sea, let alone that he was bearing down from the northwest, and was distracted by the intervention of Hood's ships to his north and east. Beatty's four surviving battlecruisers were now crossing the van of the British dreadnoughts to join Hood's three battlecruisers; in doing so, Beatty nearly rammed Rear-Admiral Arbuthnot's flagship Defence.[17]

Arbuthnot's obsolete armored cruisers had no real place in the coming clash between modern dreadnoughts, but he was attracted by the drifting hull of the crippled Wiesbaden. With Warrior, Defence closed in for the kill, only to blunder right into the gunsights of Hipper's and Scheer's oncoming capital ships. Defence was destroyed in a spectacular explosion viewed by most of the deploying Grand Fleet, sinking with all hands (903 officers and men). Warrior was hit badly but spared destruction by the mishap to the nearby superdreadnought Warspite. Warspite had been steaming near 25 knots (46 km/h) to keep pace with the 5th Battle Squadron as it tailed Beatty's battlecruisers in the run north, creating enough strain to jam her rudder. Drifting in a wide circle, she appeared as a juicy target to the German dreadnoughts and took thirteen hits, inadvertently drawing fire from the hapless Warrior. This maneuver from Warspite was known as "Windy Corner." Despite surviving the onslaught, Warspite was soon ordered back to port by Evan-Thomas.[18]

As Defence sank, Hipper moved within range of Hood's 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron. Invincible inflicted two below-waterline hits on Lützow that would ultimately doom Hipper's flagship, but at about 6:30 pm abruptly appeared as a clear target before Lützow and Derfflinger. A series of 12 inch (305 mm) shells struck Invincible, which blew up and split in two, killing all but six of her crew of 1,037 officers and men, including Rear Admiral Hood.[19]

By 6:30 p.m. the main fleet action was joined for the first time, with Jellicoe effectively "crossing Scheer's T." Jellicoe's flagship Iron Duke quickly scored a series of hits on the lead German dreadnought, König, but in this brief exchange, which lasted only minutes, as few as ten of the Grand Fleet's twenty-four dreadnoughts actually opened fire. The Germans were hampered by poor visibility in addition to being in an unfavorable tactical position. Realizing he was heading into a trap, Scheer ordered his fleet to turn and flee at 6:33 p.m. Under a pall of smoke and mist Scheer's forces succeeded in disengaging.

Conscious of the risks to his capital ships posed by torpedoes, Jellicoe did not chase directly but headed south, determined to keep the High Seas Fleet west of him. Scheer knew that it was not yet dark enough to escape and his fleet would suffer terribly in a stern chase, so at 6:55 p.m., he doubled back to the east.[20] In his memoirs he wrote, "the manœuvre would be bound to surprise the enemy, to upset his plans for the rest of the day, and if the blow fell heavily it would facilitate the breaking loose at night." But the turn to the east took his ships towards Jellicoe's.

Commodore Goodenough's 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron dodged the fire of German battleships for a second time to re-establish contact with the High Seas Fleet shortly after 7:00 p.m. By 7:15 p.m., Jellicoe had crossed the "T" yet again. This time his arc of fire was tighter and deadlier, causing severe damage to the Germans, particularly Rear-Admiral Behncke's leading 3rd Battle Squadron. At 7:17 pm, for the second time in less than an hour, Scheer turned to the west, ordering a major torpedo attack by his destroyers and a "death ride" by Scouting Group I's four remaining battlecruisers—Lützow being out of action and abandoned by Hipper—to deter a British chase. In this portion of the engagement the Germans sustained thirty-seven heavy hits while inflicting only two, Derfflinger alone receiving fourteen. Nonetheless Scheer slipped away as sunset (at 8:24 p.m.) approached. The last major engagement between capital ships took place as the surviving British battlecruisers caught up with their German counterparts, which were briefly relieved by Rear-Admiral Mauve's obsolete pre-dreadnoughts. As King George V and Westfalen exchanged a few final shots, neither side could have imagined that the only encounter between British and German dreadnoughts in the entire war was already concluded.

At 9:00 p.m., Jellicoe, knowing of the Grand Fleet's deficiencies in night-fighting, decided to try to avoid a major engagement until early dawn. He placed a screen of cruisers and destroyers behind his battle fleet to patrol the rear as he headed south to guard against Scheer's expected escape. In reality, Scheer opted to cross Jellicoe's wake and escape via Horns Reef. Luckily for Scheer, Jellicoe's scouts failed to report his true course while Jellicoe himself was too cautious to judge from extensive circumstantial evidence that the Germans were breaking through his rear.

While the nature of Scheer's escape and Jellicoe's inaction indicate the overall superiority of German night-fighting proficiency, the night's results were no more clear-cut than the battle as a whole. Southampton, Commodore Goodenough's flagship which had scouted so proficiently, was heavily damaged but managed to sink the German light cruiser Frauenlob which went down at 10:23 p.m. with all hands (320 officers and men). But at 2:00 a.m. on June 1, Black Prince of the ill-fated 1st Cruiser Squadron met a grim fate at the hands of the battleship Thüringen, blowing up with all hands (857 officers and men) as her squadron leader Defence had done hours earlier. At 2:10 a.m., several British destroyer flotillas launched a torpedo attack on the German battlefleet. At the cost of five destroyers sunk and some others damaged, they managed to sink the predreadnought Pommern with all hands (844 officers and men), as well as to torpedo the light cruiser Rostock and causing another, Elbing, to be rammed by the dreadnought Posen and abandoned. The battlecruiser Lützow was torpedoed at 1:45 a.m. on orders of her captain (von Harder) by the destroyer G38 after the surviving crew of 1,150 transferred to destroyers that came alongside.[21]

The Germans were helped in their escape by the failure of British naval intelligence in London to relay a critical radio intercept giving the true position of the High Seas Fleet. By the time Jellicoe finally learned of Scheer's whereabouts at 4:15 a.m. it was clear the battle could no longer be resumed. There would be no "Glorious First of June" in 1916.[22]

The following tables show the hits scores on individual ships. They provide good insights into when conditions favored each of the navies and an image of the standard of gunnery in both forces.

Damage to capital ships, 3:48 p.m.-4:54 p.m.

Hits on British Ships, 3:48 p.m.-4:54 p.m.

| Ship | 12 Inch | 11 Inch | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lion | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Princess Royal | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Queen Mary | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Tiger | 0 | 14 | 14 |

| New Zealand | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Indefatigable | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Barham | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 19 | 25 | 44 |

Hits on German Ships, 3:48 p.m.-4:54 p.m.

| Ship | 15 Inch | 13.5 Inch/1400lb | 13.5 Inch/1250lb | 12 Inch | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lutzow | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Derfflinger | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Seydlitz | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Moltke | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Von Der Tann | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 6 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 17 |

Damage to capital ships, 4:54 p.m.-6:15 p.m.

Hits on British ships, 4:54 p.m.-6:15 p.m.

| Ship | 12 Inch | 11 Inch | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lion | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Tiger | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Barham | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Warspite | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Malaya | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Total | 15 | 3 | 18 |

Hits on German ships, 4:54 p.m.-6:15 p.m.

| Ship | 15 Inch | 13.5 Inch/1250lb | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lutzow | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Derfflinger | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Seydlitz | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Konig | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Grosser Kurfurst | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Markgraf | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 18 | 1 | 19 |

Damage to capital ships and armored cruisers, 6:15 p.m.-7:00 p.m.

Hits on British ships, 6:15 p.m.-7:00 p.m.

| Ship | 12 Inch | 11 Inch | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invincible | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Princess Royal | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Warspite | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| Total | 20 | 0 | 20 |

Hits on German ships, 6:15 p.m.-7:00 p.m.

| Ship | 13.5 Inch/1400lb | 13.5 Inch/1250lb | 12 Inch | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lutzow | 0 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| Derfflinger | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Seydlitz | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Konig | 7 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Markgraf | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 7 | 4 | 12 | 23 |

Damage to capital ships, 7:00 p.m.-7:45 p.m.

Hits on British ships, 7:00 p.m.-7:45 p.m.

None - Hinting at how much conditions favored the Royal Navy between these times.

Hits on German ships, 7:00 p.m.-7:45 p.m.

| Ship | 15 Inch | 13.5 Inch/1400lb | 13.5 Inch/1250lb | 12 Inch | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lutzow | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Derfflinger | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Seydlitz | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Von Der Tann | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Konig | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Grosser Kurfurst | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Markgraf | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Kaiser | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Helgoland | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 14 | 4 | 5 | 14 | 37 |

Damage to capital ships and pre-dreadnoughts, 8:19 p.m.-8:39 p.m.

Hits on British ships, 8:19 p.m.-8:39 p.m.

None—Hinting at how much conditions favored the Royal Navy between these times.

Hits on German ships, 8:19 p.m.-8:39 p.m.

| Ship | 13.5 Inch/1250lb | 12 Inch | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Derfflinger | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Seydlitz | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Pommern | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Accuracy

Hits obtained by British battlecruisers and battleships

(BCS = Battlecruiser squadron) (BS = Battleship Squadron)

| Shells Fired | Hits | % Accuracy | |

| 1st and 2nd BCS | 1469 | 21 | 1.43% |

| 3rd BCS | 373 | 16 | 4.39% |

| 5th BCS | 1,099 | 29 | 2.64% |

| 2nd, 4th, 1st BS | 1,593 | 57 | 3.70% |

Hits obtained by German Battlecruisers and Battleships

(SG = Scouting Group)

| Shells Fired | Hits | % Accuracy | |

| 1st SG | 1670 | 65 | 3.89% |

| Battleships | 1927 | 57 | 2.96% |

Aftermath

At Jutland, 99 German ships sank 115,000 tons of British metal, while 151 British ships sank 62,000 tons of German steel. The British lost 6,094 seamen, the Germans 2,551. Several other ships were badly damaged, such as HMS Lion and SMS Seydlitz. At the end of the battle the British had maintained their numerical superiority and had over twenty dreadnoughts and battlecruisers still able and ready to fight while the Germans had ten.

For the British, the outcome was a slim tactical defeat. While they had lost more ships and had not destroyed the German fleet, the Germans had retreated to port and the British were in command of the area, a major factor offsetting the numerical losses—the British remained in possession of the field of battle leading many to dispute whether the battle was a tactical loss at all. Lastly, the damaged British ships were restored to operational use more quickly than the German ships, again mitigating the better performance of German naval forces.

At a strategic level the outcome was also not clear cut. The High Seas Fleet remained active and its presence as a fleet in being prevented a complete blockade of Germany. Most of the High Seas Fleet's losses were made good within a month—even Seydlitz, the most badly damaged ship to survive the battle, was fully repaired by October and officially back in service by November. Indeed, the Germans would sortie again on the August 18 and for a third time in October, although they did not find battle either time.

Self critiques

The official British Admiralty examination of their performance identified two main problems:

- Their armor-piercing shells exploded outside the German armor rather than penetrating and exploding within. As a result some German ships with only 8 inch (203 mm) armor survived hits from 15 inch (381 mm) shells. Had these shells performed to design, German losses would probably have been greater.

- Communication between ships and the British commander-in-chief were comparatively poor. For most of the battle Jellicoe had no idea where the German ships were, even though British ships were in contact. They failed to report positions contrary to the Grand Fleet Battle Plan. Some of the most important signaling was carried out solely by flag instead of wireless or using redundant methods to ensure communications—a questionable procedure given the mixture of haze and smoke that obscured the battlefield, and a foreshadowing of similar failures by habit-bound and entrenched professional officers of rank to take advantage of new technology in World War II.

Battlecruisers

The weak design and faulty use of the battlecruisers were important in the serious losses of the British. The battle is often regarded as demonstrating that the Royal Navy was technologically and operationally inferior to the German Navy. Jellicoe wrote in his dispatch:

The disturbing feature of the battle-cruiser action is the fact that five German battle-cruisers engaging six British vessels of this class, supported after the first twenty minutes, although at great range, by the fire of four battleships of the Queen Elizabeth class, were yet able to sink Queen Mary and Indefatigable … The facts which contributed to the British losses were, first, the indifferent armor protection of our battle-cruisers, particularly as regards turret armor and deck plating, and, second, the disadvantage under which our vessels labored in regard to the light … The German organization at night is very good. Their system of recognition signals is excellent. Ours is practically nil. Their searchlights are superior to ours and they use them with great effect. Finally, their method of firing at night gives excellent results. I am reluctantly compelled to the opinion that under night conditions we have a good deal to learn from them.

Procedural lapses

During the summer of 2003, a diving expedition examined the wrecks of Invincible, Queen Mary, Defence, and Lützow to investigate the cause of the British ships' tendency to suffer from internal explosions. On this evidence, a major part of the blame may be laid on lax handling of the cordite propellant for the shells of the main guns. This, in turn, was a product of current British naval doctrine, which emphasized a rapid rate of fire in the direction of the enemy rather than slower, more accurate fire.

In practice drills, emphasizing speed of firing, the cordite could not be supplied to the guns rapidly enough through the hoists and hatches; in order to bring up the propellant for the next broadside before the time when it had to be loaded, many safety doors which should have been kept shut to safeguard against flash fires were opened, bags of cordite were locally stocked and kept locally to need creating a total break down of safety design features and this "bad safety habit" carried over into real battle practices.

Furthermore, whereas the German propellant RP C/12 was supplied in brass cylinders, British cordite was supplied in silk bags, making it more susceptible to flash fires. The doctrine of a high rate of fire also led to the decision in 1913 to increase the supply of shells and cordite held on the British ships by 50 per cent, for fear of running out of ammunition; when this caused the capacity of the ships' magazines to be exceeded, cordite was stored in insecure places.[23]

The memoirs of Alexander Grant, gunner on Lion, show that some British officers were well aware of the dangers of careless handling of cordite:

With the introduction of cordite to replace powder for firing guns, regulations regarding the necessary precautions for handling explosives became unconsciously considerably relaxed, even I regret to say, to a dangerous degree throughout the Service. The gradual lapse in the regulations on board ship seemed to be due to two factors. First, cordite is a much safer explosive to handle than gun-powder. Second, but more important, the altered construction of the magazines on board led to a feeling of false security … The iron or steel deck, the disappearance of the wood lining, the electric lights fitted inside, the steel doors, open because there was now no chute for passing cartridges out; all this gave officers and men a comparative easiness of mind regarding the precautions necessary with explosive material.

After the battle the Admiralty produced a report critical of the cordite handling practices. By this time, however, Jellicoe had been promoted to First Sea Lord and Beatty to command of the Grand Fleet; the report, which indirectly placed part of the blame for the disaster on the fleet's officers, was closely held, and effectively suppressed from public scrutiny.

Flawed paradigm

Other analysis of the battle showed that the British concept and use of the battlecruiser was wholly flawed. The battlecruiser had been designed according to Jackie Fisher's dictum that "speed is armor." They were intended to be faster than battleships, with superior fire control, and able to pound lighter enemy cruisers at ranges at which the enemy could not reply. In the event, the whole concept was negated when British battlecruisers were asked to fight German ships which were just as fast, exercised better gunnery, and were better armored instead of holding the enemy beyond his maximum range.

Controversy

At the time Jellicoe was criticized for his caution and for allowing Scheer to escape. Beatty in particular was convinced that Jellicoe had missed a tremendous opportunity to win another Trafalgar and annihilate the High Seas Fleet. Jellicoe's career stagnated; he was promoted away from active command to become First Sea Lord, while Beatty replaced him as commander of the British Grand Fleet.

The controversy raged within the Navy for about a decade after the war. Criticism focused on Jellicoe's decision at 7:15 p.m. Scheer had ordered his cruisers and destroyers forward in a torpedo attack to cover the turning away of his battleships. Jellicoe chose to turn away to the southeast and so keep out of range of the torpedoes. If Jellicoe had instead turned to the west, could his ships have dodged the torpedoes and destroyed the German fleet? Supporters of Jellicoe, including the naval historian Julian Corbett, pointed out the folly of risking defeat in battle when you already have command of the sea. Jellicoe himself, in a letter to the Admiralty before the battle, had stated that in the event of a fleet engagement in which the enemy turned away he would assume that the intention was to draw him over mines or submarines and he would decline to be so drawn. This appreciation was at the time accepted by the Admiralty. (Corbett's volume of the official history of the war, Naval Operations, contains the extraordinary disclaimer, "Their Lordships find that some of the principles advocated in the book, especially the tendency to minimize the importance of seeking battle and forcing it to a conclusion, are directly in conflict with their views.")[24]

Whatever one thinks of the result, it is true that the stakes were very high, the pressure on Jellicoe was immense, and his caution is certainly understandable—his judgment might have been that even 90 percent odds in favor were not good enough on which to bet the British Empire. The former First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, said of the battle that Jellicoe "was the only man on either side who could have lost the war in an afternoon."

The criticism of Jellicoe also fails to give enough credit to Scheer, who was determined to preserve his fleet by avoiding a decisive engagement, and showed great skill in effecting his escape.

Beatty's actions

Another school of thought condemns the actions of Admiral Beatty for the failure of a complete British victory. Although Beatty was undeniably a brave man, his encounter with the High Seas Fleet almost cost the British the battle. Most of the British losses in tonnage occurred in Beatty's squadron. The three capital ships the British lost that day were all under the command of Beatty.

Beatty's lack of control over the battlecruiser action is often criticised. Moreover, some claim his main failure was in that he failed to provide Jellicoe with precise information on the whereabouts of the High Seas Fleet and ensure communications redundancy was used. Beatty did not apparently appreciate the finer points of command and control over a naval engagement, or the potential weaknesses of his own ships. Beatty, aboard the battlecruiser Lion, repeatedly overlooked the four fast battleships of the 5th Battle Squadron under his command, engaging with six ships when better control could have given him 10 against Hipper’s five. Despite Beatty's 12" and 13.5" guns having greater range than Hipper's 11" guns, Beatty closed the gap between the opposing squadrons until the Germans' superior gunnery took its toll.

Even his famous remark, "There's something wrong with our bloody ships today," could be construed as Beatty seeking to deflect blame away from himself. Despite his poor control of his battlecruisers, his neglect of the 5th Battle Squadron and inadequate battle preparedness, Beatty was fully prepared to lambaste Admiral Jellicoe for not being aggressive enough; even though during the course of the battle Beatty, and Admiral Arbuthnot, had shown the folly of charging in for the attack. Jellicoe clearly understood the capabilities of his ships and the risks he faced; it is not clear that Beatty did.

Losses

British

- Battlecruisers Indefatigable, Queen Mary, Invincible

- Armored cruisers Black Prince, Warrior, Defence

- Flotilla Leaders Tipperary

- Destroyers Shark, Sparrowhawk, Turbulent, Ardent, Fortune, Nomad, Nestor

German

- Battlecruiser Lützow

- Pre-Dreadnought Pommern

- Light cruisers Frauenlob, Elbing, Rostock, Wiesbaden

- (Heavy Torpedo Boats) Destroyers V48, S35, V27, V4, V29

Honours from Jutland

Victoria Cross

- The Hon. Edward Barry Stewart Bingham (HMS Nestor)

- John Travers Cornwell (HMS Chester)

- Francis John William Harvey (HMS Lion)

- Loftus William Jones (HMS Shark)

Status of the survivors and wrecks

On the 90th anniversary of the battle, in 2006, the Ministry of Defence announced that the 14 British vessels lost in the battle were being designated as protected places under the Protection of Military Remains Act. The last living veteran of the battle is Henry Allingham, a British RAF (originally RNAS) airman, aged 111 in 2007.[25]

Quotations

- "Two short siren blasts rang out over the water as the main battle fleet, steaming in four groups, turned to port to form themselves in a single line of battle—the last line ahead battle formation in the history of the British navy. Not wooden walls this time, but walls of steel, with streamlined gray hulls instead of gilded stern galleries and figureheads, and funnels belching black smoke instead of sails close-hauled. But it was a formation Blake or Rooke or Rodney would have recognized, and approved. King George V and Ajax were first, followed by Orion, Royal Oak, Iron Duke, Superb, Thunderer, Benbow, Bellerophon, Temeraire, Collingwood, Colossus, Marlborough, St. Vincent—twenty-seven in all, names redolent with the navy's past […], names of admirals and generals, Greek heroes and Roman virtues. And all slowly bringing their guns to bear as they steamed into harm's way—just as their predecessors had for so many centuries in exactly the same sea. […] Scheer's position was dangerous but hardly hopeless. [...] Scheer might have looked to his heavier armor to protect his ships from British shells (many of which were defective and failed to explode), while overpowering theirs with his own faster and more accurate fire. Certainly this was the moment of decisive battle he and Tirpitz had been yearning for. But as Scheer gazed out at the flashing fire along the horizon, he saw something else. He saw before him the entire history of the British navy, a fighting force with an unequaled reputation for invincibility in battle and bravery under fire." "The English fleet […] had the advantage of looking back on a hundred years of proud tradition which must have given every man a sense of superiority based on the great deeds of the past." His own navy's fighting tradition was less than two years old. At that fateful moment, Scheer was confronting not John Jellicoe but the ghosts of Nelson, Howe, Rodney, Drake, and the rest; and he backed down."[26]

- “The High Seas Fleet [of Imperial Germany], developed in only sixteen years, had proved itself able to face the full might and tradition of British seapower and survive. [A variety of grave shortcomings] point to the underlying reason for the shock which Jutland administered to British pride. Already the balance of energy and vigor had begun to shift. Already the leadership in competitive endeavor had crossed the North Sea and was crossing the North Atlantic. In a sector crucial to national survival, the onset of British decline, hidden for a generation behind the splendors of the old order, was revealed. Few recognized the deeper perspectives at the time; most were concerned to argue and explain the foreground event. […] Because it seemed so indecisive, Jutland was sometimes called ‘the battle that was never fought.’ It was in fact one of the more decisive battles of modern history. For it was one of the first clear indications to Britain that the creator had become the curator.”[27]

Notes

- ↑ John Costello and Terry Hughes, Jutland 1916 (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976, ISBN 9780030184666), 105.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 110.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 111.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 126-29.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 132-33.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 136-38.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 138.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 139.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 144-45.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 140.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 149.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 156.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 162.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 163-65.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 169-70.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 168.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 172.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 172-73.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 177-78.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 182.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 204-07, 216.

- ↑ Costello and Hughes, 217.

- ↑ Nicholas A. Lambert, "Our Bloody Ships" or "Our Bloody System? Jutland and the Loss of the Battle Cruisers 1916," The Journal of Military History 61, (January 1998): 36.

- ↑ Julian Corbett, Naval Operations (London: Longmans & Co., 2003, ISBN 978-1843424895).

- ↑ BBC News, Britain's oldest veteran recalls WWI. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ↑ Arthur Herman, To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World (New York: Harper Perennial, 2005, ISBN 9780060534240).

- ↑ Stuart Legg, Jutland, an Eye-Witness Account of a Great Battle (New York: The John Day Company, 1966).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bacon, Reginald. The Jutland Scandal. London: Hutchinson & Co., 1925.

- BBC News. Britain's oldest veteran recalls WWI. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Bonney, George. The Battle of Jutland, 1916. Portsmouth: Royal Naval Museum Publications, 2002. ISBN 9780750929264

- Butler, Daniel Allen. Distant Victory: The Battle of Jutland and the Allied Triumph in the First World War. New York: Praeger Publishers, 2006. ISBN 0275990737

- Corbett, Julian. Naval Operations. Vol. 3, Official History of the War. London: Longmans & Co., 2003. ISBN 1843424916

- Costello, John, and Terry Hughes. Jutland 1916. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976 ISBN 9780030184666

- George, S. C. Jutland to Junkyard. Edinburgh: Paul Harris Publishing, 1981. ISBN 086228029X

- Gordon, Andrew. The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command. London: John Murray, 1996 ISBN 9781557507181

- Herman, Arthur. To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World. New York: Harper Perennial, 2005 ISBN 9780060534240

- Hough, Richard. Dreadnought, A history of the Modern Battleship. New York: MacMillan Publishers, 1975 ISBN 9780517293676

- Lambert, Nicholas A. "Our Bloody Ships" or "Our Bloody System? Jutland and the Loss of the Battle Cruisers 1916." The Journal of Military History 61 (January 1998): 29–55.

- Legg, Stuart. Jutland, an Eye-Witness Account of a Great Battle. New York: The John Day Company, 1966.

- London, Charles. Jutland 1916, Clash of the Dreadnoughtss. New York: Osprey Publishing, 2000.

- Marder, Arthur J. From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Massie, Robert K. Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House, 2003. ISBN 0345408780

- Steel, Nigel, and Peter Hart. Jutland 1916: Death in the Grey Wastes. London: Cassell, 2004. ISBN 0304358924

- Tarrant, V. E. Jutland: The German Perspective—A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994 ISBN 9781557504081

External links

All links retrieved September 22, 2023.

- Beatty's official report

- Jellicoe's official dispatch

- Last known survivor of the Battle of Jutland by Henry Allingham

- Jutland Casualties Listed by Ship

Notable accounts

- Kiplings' Reporting on The Battle of Jutland

- Battle of Jutland Memoir by Alexander Grant, a gunner aboard HMS Lion.

- SMS Seydlitz at Jutland by Moritz von Egidy, captain of SMS Seydlitz.

- The Sea Battle Off the Skagerrak on 31 May 1916 by Richard Foerster, gunnery officer on Seydlitz.

- The Battle of the Skagerrak (Jutland) by Georg von Hase, gunnery officer on Derfflinger.

(Note that due to the time zone difference, the times in some of the German accounts are two hours ahead of the times in this article.)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.