Al-Mansur

Abu Ja'far Abdallah ibn Muhammad al-Mansur (712–775; Arabic: ابو جعفر عبدالله ابن محمد المنصور) was the second Abbasid Caliph, succeeding his brother, As-Saffah. He was born at al-Humaymah, the home of the 'Abbasid family after their emigration from the Hejaz in 687–688. His father, Muhammad, was a great-grandson of 'Abbas; his mother was a Berber woman. He reigned from 754 until 775. In 762 he founded as new imperial residence and palace city Madinat as-Salam, which became the core of the Imperial capital Baghdad. In many respects, al-Mansur is the true founder of the Abbasid dynasty. His brother had led the revolt against the Umayyads but died before he could consolidate his achievements. Baghdad quickly began to shine as a center of learning and of all things Islamic. The tradition of patronizing scholarship established by al-Mansur was a vital one, which enriched not only the Muslim world but the wider world beyond.

In beginning to re-Islamize the caliphate, al-Mansur launched a process that was invaluable in reinvigorating the Islamic ideal that the whole of human life stands under divine guidance, that spiritual and temporal aspects must be integrated, not separated. He laid the foundations for what is widely acknowledged as a "Golden Age." Although the caliphate would disintegrate even before Baghdad fell in 1258 and rival caliphates would compete for the leadership of the Muslims world, Al-Mansur's heirs would reign over one of the most unified, prosperous and often peaceful period in Islam's history.

Biography

After a century of Umayyad rule, al-Mansur's brother, As-Saffah al-Abbas led a successful revolt against the Damascus based caliphate, although a branch of the family continued in Andalusia, where they later re-claimed the title of caliph. Much of what is written about the Umayyad period is through the lens of the critics. The criticism is that they ruled the caliphate as if it were a "monarchy," appointing relatives and allied Arabs to posts to the disadvantage of non-Arabs. They are said to have side-lined Islam, ruling by edict and guided by their own opinions. Al-Mansur's father attracted support for his revolt because he promised to rule according to Shari'ak, that is, to be guided by the Qur'an and the Sunnah of Muhammad. Their rallying cry was "O Muhammad, O helped of God."[1] It was from this slogan that al-Mansur received his name, which means "victorious" or "helped." They may also have hoped to heal the rift between Shi'a and Sunni due to al-Abbas' familial relationship with Muhammad; he was descended from Muhammad's uncle. Although fitna or causing division within the ummah (community of Islam) is considered a crime, al-Abbas argued that revolt against the Umayyads was a justified battle against oppression; his war-banner read, "Leave is given to those who fight because they were wronged," which cites Q22: 39, the earliest verse permitting self-defense. Marwan II was defeated at the Battle of the Great Zab River in 750.

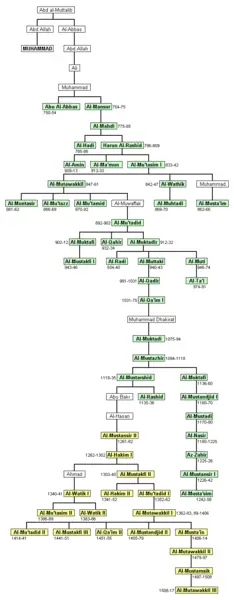

Al-Abbas became the first Abbasid and the 19th caliph. Although some supporters may have hoped for a return to the original system of choosing a caliph from qualified and pious candidates, ending the principle of dynastic succession established by the Umayyads, al-Abbas took steps to secure succession within his family.[2] Technically, the heir was designated then recognized by oath-taking. However, the reigning caliph would require the elite to pledge their fealty to the heir-apparent before his own death.[3] Al-Mansur was designated to succeed his brother, and did so in 754, becoming the 2nd caliph of his dynasty and the 17th since Muhammad's death. Since all subsequent Abbasid caliphs descended from his lineage, he can effectively be considered to have founded the dynasty.

As caliph

Al-Mansur saw himself as the universal ruler with religious and secular authority. The hope that Shi'a and Sunni might reconcile their differences was not realized, although his son, Al-Mahdi would continue to attempt rapprochement. In 672, he crushed a revolt against his rule by Nafs az-Zakiya, a Shiite rebel in Southern Iraq and alienated Shiite groups. They had been hoping that an 'Abbasid victory would restore the caliphate to the Imamate, and that the rule of the "Al Muhammad," the family of the prophet would begin. Many were disappointed. In 755 he arranged the assassination of Abu Muslim. Abu Muslim was a loyal freed man who had led the Abbasid forces to victory over the Umayyads during in the Third Islamic Civil War in 749-750. At the time of al-Mansur he was the subordinate, but undisputed ruler of Iran and Transoxiana. The assassination seems to have been made to preclude a power struggle in the empire. His death secured the supreme rule of the Abbasid family.

During his reign, literature and scholarly work in the Islamic world began to emerge in full force, supported by new Abbasid tolerances for Persians and other groups suppressed by the Umayyads. Although the Umayyad caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik had adopted Persian court practices, it was not until al-Mansur's reign that Persian literature and scholarship were truly appreciated in the Islamic world. The emergence of Shu'ubiya among Persian scholars occurred during the reign of al-Mansur as a result of loosened censorship over Persian nationalism. Shu'ubiya was a literary movement among Persians expressing their belief that Persian art and culture was superior to that of the Arabs; the movement served to catalyze the emergence of Arab-Persian dialogues in the eighth century. Al-Mansur also founded the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. He started building the city in 762, using a circular plan.

Perhaps more importantly than the emergence of Persian scholarship was the conversion of many non-Arabs to Islam. The Umayyads actively tried to discourage conversion in order to continue the collection of the jizya, or the tax on non-Muslims. The inclusiveness of the Abbasid regime, and that of al-Mansur, saw the expansion of Islam among its territory; in 750, roughly 8 percent of residents in the Caliphate were Muslims. This would double to 15 percent by the end of al-Mansur's reign.

In 772 Al Mansur ordered Christians and Jews in Jerusalem to be stamped on their hands with a distinctive symbol.

According to Shiite sources, the scholar Abu Hanifa an-Nu'man was imprisoned by al-Mansur and tortured. He also had Imam Malik, the founder of another school of law, flogged.[4] The caliphs, in theory, were subject to the Shari'ah; they did not possess any privileged authority to interpret this, unlike the Shi'a Imams. However, since they symbolized the unity of the community and were also the commanders of the faithful, they increasingly saw themselves as the directly representing God on earth. However, it was scholars such as Abu Hanifa and Imam Malik who were codifying the hadith and Islamic jurisprudence, and they did not consider the caliph qualified to intervene. This created tension, which continued during much of the early Abbasid caliphate, between the Caliph and the religious scholars. Al-Mansur's successor began to exert the right to determine orthodoxy, which later developed into a type of inquisition known as the minha (830-845). Later, the Abbsids dropped the "prophet" from their title of "deputy of the prophet of God," using instead "deputy of God." This may not have occurred until the time of Al-Ma'mun (813-33).[5]

However, al-Mansur began the process of replacing the secular judges appointed by the Umayyads with Islamic judges, or qaadah (singular, qadi).[6] Although tension developed between Caliphs and the religious scholars, al-Mansur helped to place Islam at the center of life, law, morality and every aspect of life.

Death and Succession

Al-Mansur died in 775 on his way to Mecca to make hajj. He was buried somewhere along the way in one of the hundreds of graves that had been dug in order to hide his body from the Umayyads. He was succeeded by his son, al-Mahdi, a name he had chosen because of the association with the Mahdi legend, that one would come who would establish peace and justice.[7]

Character

Al-Masudi in Meadows of Gold recounts a number of anecdotes that present aspects of this caliphs character. He tells of a blind poet on two occasions reciting praise poems for the Umayyads to one he didn't realize was this Abbasid caliph. Al-Mansur rewarded the poet for the verses. Al-Masudi relates a tale of the arrow with verses inscribed on feathers and shaft arriving close to al-Mansur. These verses prompted him to investigate the situation of a notable from Hamadan unjustly imprisoned and release him. There is also the account of the foreboding verses al-Mansur saw written on the wall just before his death.

A very impressive aspect of this caliph's character is that when he died he left in the treasury six hundred thousand dirhams and fourteen million dinars. Al-Mahdi used this money in his efforts to build a bridge between Sunni and Shi'a, presenting gifts to the latter.

Legacy

Al-Mansur, in many respects, is the true founder of the Abbasid dynasty. His brother had led the revolt against the Umayyad' but died before he could consolidate his achievements. In moving the capital to Baghdad, the city that history would indelibly link with the dynasty, al-Mansur provided his heirs with a city that would shine as a center of learning and of all things Islamic. From the start, the city was an Islamic city, a showcase for Islamic architecture and Islamic culture. The City was designed to invoke visions of paradise. The tradition of patronizing scholarship was a vital one, which would enrich not only the Muslim world but the wider world beyond. Many Greek texts were translated into Arabic and later reached Europe through Andalusia. In re-Islamizing the caliphate, a process that began under al-Mansur, the Abbasids played an invaluable role in reinvigorating the Islamic ideal that the whole of human life stands under divine guidance, that spiritual and temporal aspects must be integrated, not separated. Although towards the end of their Caliphate, use of reason in Islamic discourse became suspect, the earlier flowering of learning Muslim scholars imbued all areas of knowledge with religious values, arguing that knowledge must always serve a higher purpose.

A monument to Al-Mansur was damaged in an explosion in Baghdad during 2005. This was repaired and unveiled June 29, 2008.

| Preceded by: As-Saffah |

Caliph 754–775 |

Succeeded by: Al-Mahdi |

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bennett, Clinton. 1998. In Search of Muhammad. London, UK: Cassell. ISBN 9780304337002

- Bewley, Aisha Abdurrahman. 1998. A glossary of Islamic terms. London, UK: Ta-Ha. ISBN 9781897940785

- Fisher, W.B., Ilya Gershevitch, Ehsan Yarshater, R.N. Frye, J.A. Boyle, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, Peter Avery, Gavin Hambly, and Charles Melville. 1968. The Cambridge history of Iran. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521069359

- Glassé, Cyril. 2008. The new encyclopedia of Islam. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742562967

- Hanne, Eric J. 2007. Putting the caliph in his place: power, authority, and the late Abbasid Caliphate. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 9780838641132

- Kennedy, Hugh. 2005. When Baghdad ruled the Muslim world: the rise and fall of Islam's greatest dynasty. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780306814358

- Lewis, Bernard. 1991. The political language of Islam. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226476933

- Mas'udi, Paul Lunde, and Caroline Stone. 1989. The meadows of gold: the Abbasids. London, UK: Kegan Paul. ISBN 9780710302465

- Muir, William, and T.H. Weir. 2004. The Caliphate: its rise, decline and fall from original sources. New Delhi, IN: Cosmo. ISBN 9788130700090

- Ṭabarī, and Jane Dammen McAuliffe. 1995. Àbbāsid authority affirmed. SUNY series in Near Eastern studies. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780585147932

- Wiet, Gaston. 1971. Baghdad; metropolis of the Abbasid caliphate. The Centers of civilization series. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806109220

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.