Yahweh

Yahweh1 (ya·'we) in the Bible, the God of the people of ancient Israel. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam —though sometimes using different names to describe him — all affirm that Yahweh alone is God. Jews normally do not pronounce this name of God, considering it too holy to verbalize. Instead they refer either to Adonai, Elohim, or Hashem (see below). In Christian Bibles, Yawheh is usually translation as "the Lord," a rough equivalent to the Hebrew Adonai. Muslims refer to God as "Allah," which originates from the same etymological root as "Elohim."

While the original concept of Yahweh may not have been monotheistic — other gods may also have been acknowledged as existing — the Israelite prophets insisted that the people of Israel must worship him alone. Monotheism, centered on Yahweh, eventually became the normitive Jewish religion, and this in turn was inherited by both Christianity and Islam. Yahwist monotheism has also come to inflluence other religions through the centuries, both as the result of missionary activity and interreligious dialogue.

The historical contribution of Yahwism is a mixed one. The prophetic tradition affirmed true belief in Yahweh as an alternative to such evils as human sacrifice, immoral fertility cults, idolatry, priestly corruption, and superstition. On the other hand, Yahwism and its montheistic offspring have sometimes been used to justify tribal warfare, the repression of rival religions, the persecution and murder of heretics and "pagans," and even genocide.

"Jehovah" is a modern mispronunciation of the Hebrew name Yahweh, resulting from combining the consonants of that name, YHWH, (formerly transcribed "JHVH") and using other vowels.

Derivation

Biblical Tradition

The Bible presents several stories regarding the revelation of God's true name, Yahweh. The best known is the story of Moses and the burning bush of Exodus 3. Shortly after this, God makes it clear that Moses is the first to know the secret of the divine name:

- God also said to Moses, "I am the Lord. I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac and to Jacob as God Almighty, but by my name the Lord I did not make myself known to them. (Ex. 6:2-3)

In this paragraphy three names of God are used: Elohim (God), the Lord (YHWH), and El Shaddai (God Almighty). In Genesis 35:7, God appears to Jacob at "El-Bethel," (Bethel meaning literally the house or place of El), so named because of God's manifesting himself there. El-Shaddai (God Almighty) appears more than 30 times in the Hebrew Bible — Gen. 28:3; 35:11, etc.). Elohim (a plural version of El — Gen. 1:1, etc.) is used many hundreds of times. Outside the Bible, El is known as the chief diety of the Canaanite religion. He was the father of the Canaanite god Baal and the husband of the mother goddess Ashera. (Interestingly, the word "Baal" also means "Lord.")

A problem for biblical scholars is the fact that the Book of Genesis appears to contradict the story in Exodus regarding the first time that humans came to known God's true name. Gen 2:19 says that it was in the days of Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve. Gen. 12:8 specifies that at Bethel (the "place of El") Abraham called on the name of the Lord some 400 years before Moses. The first woman mentioned as calling on the name of the Lord is Abraham's wife Sarah. (Gen. 16:13)

The Catholic scholar A.J. Maas suggested one way of resolving the seeming contradiction: that people knew at least a syllable of God's true name, and began calling themselves after it, long before the whole name was revealed to Moses:

- Among the 163 proper [biblical] names which bear an element of the sacred name in their composition, 48 have yeho or yo at the beginning, and 115 have yahu or yah and the end, while the form Jahveh [Yahweh] never occurs in any such composition. Perhaps it might be assumed that these shortened forms yeho, yo, yahu, yah, represent the Divine name as it existed among the Isralites before the full name Jahveh was revealed on Mt. Horeb. [1]

A Non-Hebraic Diety?

A more fundamental question is whether the name Yahweh originated among the Israelites or was adopted by them from some other people and speech. The Exodus story tells us that they Israelites had not been worshippers of Yahweh — at least by that name — before the time of Moses. The revelation of the name to Moses was made at Sinai/Horeb, a mountain sacred to Yahweh, far to the south of Palestine, in a region where the forefathers of the Israelites had never roamed, and in the territory of other tribes. Long after the settlement in Canaan this region continued to be regarded as the abode of Yahweh (Judg. 5:4; Deut. 33:3; I Kings 19:8, etc). Moses is closely connected with the tribes in the vicinity of the holy mountain.

According to one account, his wife was a daughter of Jethro, a priest of Midian (Ex. 18). When Moses led the Israelites to this mountain after their deliverance from Egypt, Jethro came to meet him, extolling Yahweh as greater than all the other gods. The Midianite Jethro "brought a burnt offering and other sacrifices to God" at which the chief men of the Israelites were his guests. It might appear, therefore, that in the tradition followed by this biblical author, the tribes within whose pasture lands the mountain of God stood were already worshippers of Yahweh — although not exclusively — before the time of Moses. Some scholars have surmised that the name Yahweh belonged originally to their speech, rather than to that of Israel.

Alternative derivations

The attempts to connect the name Yahweh with that of an Indo-European deity (Jehovah-Jove, &c.), or to derive it from Egyptian or Chinese, may be passed over. But one theory which has had considerable currency requires notice, namely, that Yahweh, or Yahu, Yaho,3 is the name of a god worshipped throughout the whole, or a great part, of the area occupied by the Western Semites. In its earlier form this opinion rested chiefly on certain misinterpreted testimonies in Greek authors about a god law, and was conclusively refuted by Baudissin; recent adherents of the theory build more largely on the occurrence in various parts of this territory of proper names of persons.2 The divergent Judæan tradition, according to which the forefathers bad worshipped Yahweh from time immemorial, may indicate that Judah and the kindred clans had in fact been worshippers of Yahweh before the time of Moses.

The form Ya ha, or Yaho, occurs not only in composition, but by itself; see Aramaic Papyri discovered at Assaan, B 4,6, ir ; E 14;

In Greek texts

This is doubtless the original of Iaw, frequently found in Greek authors and in magical texts as the name of the God of the Jews and places which they explain as compounds of Yahu or Yah.4 The explanation is in most cases simply an assumption of the point at issue; some of the names have been misread; others are undoubtedly the names of Jews. There remain, however, some cases in which it is highly probable that names of nonIsraelites are really compounded with Yahweh. The most conspicuous of these is the king of Hamath who in the inscriptions of Sargon (722705 B.C.E.) is called Yaubidi and Ilubidi (compare Jehoiakim-Eliakim). Azriyau of Jaudi, also, in inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser (745-728 B.C.E.), who was formerly supposed to be Azariah (Azziah) of Judah, is probably a king of the country in northern Syria known to us from the Zenjirli inscriptions as Jadi.

Mesopotamian influence

Friedrich Delitzsch brought into notice three tablets, of the age of the first dynasty of Babylon, in which he read the names of Va- a-ve-ilu, Va-ve-ilu, and Va-u-urn-un ( Yahweh is God ), and which he regarded as conclusive proof that Yahweh was known in Babylonia before 2000 B.C.E.; he was a god of the Semitic invaders in the second wave of migration, who were, according to Winckler and Delitzsch, of North Semitic stock (Canaanites, in the linguistic sense). We should thus have in the tablets evidence of the worship of Yahweh among the Western Semites at a time long before the rise of Israel. The reading of the names is, however, extremely uncertain, not to say improbable, and the far-reaching inferences drawn from them carry no conviction. In a tablet attributed to the I4th century B.C.E. which Sellin found in the course of his excavations at Tell Taannuk (the Tanakh of the O.T.) a name occurs which may be read Aiji-Yawi (equivalent to Hebrew Ahijah) 6 if the reading be correct, this would show that Yahweh was worshipped in Central Palestine before the Israelite conquest. The reading is, however, only one of several possibilities. The fact that the full form Yahweh appears, whereas in Hebrew proper names only the shorter Yahu and Yah occur, weighs somewhat against the interpretation, as it does against Delitzsch's reading of his tablets.

It would not be at all surprising if, in the great movements of populations and shifting of ascendancy which lie beyond our historical horizon, the worship of Yahweh should have been established in regions remote from those which it occupied in historical times; but nothing which we now know warrants the opinion that his worship was ever general among the Western Semites.

Many attempts have been made to trace the West Semitic Yahu back to Babylonia. Thus Dehitzsch formerly derived the name from an Akkadian god, I or Ia; or from the Semitic nominative ending, Yau; but this deity has since disappeared from the pantheon of Assyriologists. The combination of Yahweh with Ea, one of the great Babylonian gods, seems to have a peculiar fascination for amateurs, by whom it is periodically discovered. Scholars are now agreed that, so far as Yahu or Yah occurs in Babylonian texts, it is as the name of a foreign god.

Possible origins

A common suggestion, as articulated by biblical scholar Mark S. Smith in The Origins of Biblical Monotheism, is that the Israelite Yahweh was derived from the traditions of the Shasu, linguistically Canaanite nomads from southern transjordan. An Egyptian inscription from the Temple of Amun at Karnak from the time of Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1390-1352 B.C.E.) refers to the "Shasu of Yhw," evidence that this god was worshipped among some of the Shasu tribes at this time. Biblical archaeologist Amihai Mazar, in Archaeology of the Land of the Bible Volume I, suggests that the association of Yahweh with the desert may be the product of his origins in the dry lands to the south of Israel. Egyptologist Donald Redford, in Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, suggests that the Israelites themselves may have been a group of Shasu who moved northward into Canaan in the 13th century B.C.E., appearing for the first time in the stele of Merenptah, and as Israel Finkelstein has shown in The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts settled the Samarian and Judean hills at this time.

Van der Toorn's article "Yahweh" in the Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible notes that, although a wide range of opinions have been presented, no clear etymology for the tetragrammaton presents itself.

Hebraist Joel M. Hoffman, in Chapter 4 of In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language, argues that the Tetragrammaton was purposely composed only and entirely of matres lectiones. (See also Elohim.)

Tetragrammaton

In such cases of substitution the vowels of the word which is to be read are written in the Hebrew text with the consonants of the word which is not to be read (see Q're perpetuum). The consonants of the word to be substituted are ordinarily written in the margin; but inasmuch as Adonai was regularly read instead of the ineffable name YHWH, it was deemed unnecessary to note the fact at every occurrence. When Christian scholars began to study the Old Testament in Hebrew, if they were ignorant of this general rule or regarded the substitution as a piece of Jewish superstition, reading what actually stood in the text, they would inevitably pronounce the name Jehova. It is an unprofitable inquiry who first made this blunder; probably many fell into it independently. The statement still commonly repeated that it originated with Petrus. These details are scarcely the invention of the chronicler; see CHRONICLES, and Expositor, Aug. 1906, p. 191.

1Though the original pronunciation of the consonantally-written name YHWH is not known with certainty, linguistic scholars generally consider Yahwheh to be most probable, and this form is the one generally used in the separate articles throughout this encyclopedia. (See: Wikisource:Yahweh)

The Tetragrammaton (Greek: τετραγράμματον; "word with four letters") is the usual reference to the Hebrew name for God, which is spelled (in the Hebrew alphabet): י (yodh) ה (heh) ו (vav) ה (heh) or יהוה (YHWH). It is the distinctive personal name of the God of Israel.

Of all the names of God, the one which occurs most frequently in the Hebrew Bible is the Tetragrammaton, appearing 6,823 times, according to the Jewish Encyclopedia. The Biblia Hebraica and Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia texts of the Hebrew Scriptures each contain the Tetragrammaton 6,828 times.

In Judaism, the Tetragrammaton is the ineffable name of God, and is therefore not to be read aloud. In the reading aloud of the scripture or in prayer, it is replaced with Adonai ("My Lords", commonly rendered as "the Lord"). Other written forms such as י (yod) ו (vav) (YW or Yaw); or י (yod) ה (heh) (YH or Yah) are read in the same way.

Outside of direct prayer, the word "’ǎdônây" (אֲדֹנָי) is not spoken by some Jews since to do so is considered a violation of the commandment not to use the Lord's name in vain (Exodus 20:7). Therefore, the word is often read as HaShêm (הַשֵּׁם) literally, "The Name") or in some cases ’ǎdô-Shêm, a composite of ’ǎdônây and HaShêm. A similar rule applies to the word ’ělôhîym ("God"), which some Jews intentionally mispronounce as ’ělôkîym for the same reason. (In a process analogous to the "euphemism treadmill", a prosaic substitute for the Tetragrammaton during one historical period may acquire sanctity and thus itself be considered too holy for ordinary use in subsequent periods.)

Meaning

According to one Jewish tradition, the Tetragrammaton is related to the causative form, the imperfect state, of the Hebrew verb הוה (ha·wah, "to be, to become"), meaning "He will cause to become" (usually understood as "He causes to become"). Compare the many Hebrew and Arabic personal names which are 3rd person singular imperfective verb forms starting with "y", e.g. Hebrew Yôsêph = Arabic Yazîd = "He [who] adds"; Hebrew Yiḥyeh = Arabic Yahyâ = "He [who] lives".

Another tradition regards the name as coming from three different verb forms sharing the same root YWH, the words HYH haya היה: "He was"; HWH howê הוה: "He is"; and YHYH yihiyê יהיה: "He will be". This is supposed to show that God is timeless, as some have translated the name as "The Eternal One". Other interpretations include the name as meaning "I am the One Who Is." This can be seen in the traditional Jewish account of the "burning bush" commanding Moses to tell the sons of Israel that "I AM אהיה has sent you." (Exodus 3:13-14) Some suggest: "I AM the One I AM" אהיה אשר אהיה, or "I AM whatever I need to become". This may also fit the interpretation as "He Causes to Become." Many scholars believe that the most proper meaning may be "He Brings Into Existence Whatever Exists" or "He who causes to exist".

The name YHWH was not always applied to a monotheistic God: see Asherah and other gods, Elohim (gods) and Yaw (god).

Transcription

Using consonants as semi-vowels

In Biblical Hebrew, most vowels are not written and the rest are written only ambiguously, as the vowel letters double as consonants (similar to the Latin use of V to indicate both U and V). See Matres lectionis for details. For similar reasons, an appearance of the Tetragrammaton in ancient Egyptian records of the 13th century B.C.E. sheds no light on the original pronunciation. 2. Therefore it is, in general, difficult to deduce how a word is pronounced from its spelling only, and the Tetragrammaton is a particular example: two of its letters can serve as vowels, and two are vocalic place-holders, which are not pronounced. Not surprisingly then, Josephus in Jewish Wars, chapter V, wrote, "…in which was engraven the sacred name: it consists of four vowels". In Greek, they are Ιαου, which comes out to Yau, since iota is used to represent semi-vocalic 'y' (and omicron+ypsilon="oo").

Further, Josephus's four vowels are confirmed by theophoric stems in personal names, always: Yaho/Yahu/Y:ho/Y:hu.[2] These yield in English Yau and Yao, which are pronounced the same. Once again, the heh is not pronounced here in Hebrew, but is used instead as a place holder. Moreover, Gnostic texts, such as those Marcion wrote, discuss the Judaic god extensively, and spell the Tetragrammaton in Greek, Ιαω, that is "Yao." Lastly, Levantine texts (including those from ancient Ugarit) render the Tetragrammaton Yaw, pronounced "Yau."[3]

Jewish use of the word

In Judaism, pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton is a taboo; it is widely considered forbidden to utter it and the pronunciation of the name is generally avoided. Usually, Adonai is used as a substitute in prayers or readings from the Torah. When used in everyday speaking (or according to many) in learning the Tetragrammaton is replaced by HaShem. The difference is marked by the vowelization in printed Bibles—the Tetragrammaton takes on the vowels of the word whose pronunciation it takes. Torah scrolls have no diacritical vowel marks, and therefore the reader must memorize the correct pronunciation for each instance of the Tetragrammaton (as for every word he reads).

According to rabbinic tradition, the name was pronounced by the high priest on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement as well as the only day when the Holy of Holies of the Temple would be entered. With the destruction of the Second Temple in the year 70, this use also vanished, also explaining the loss of the correct pronunciation. (In one midrashic tradition, only seven Cohanim, or individuals of priestly lineage, know the true name of God, and it is passed down throughout the generations to be ready for invocation during the building of the Third Jewish Temple.)

There is a Jewish tradition that the actual name of God, only known to and stated by the high priest, was actually 72 letters long. The name was written out on a long strip of parchment, then folded and slipped inside the fold of the high priest's bejeweled breastplate. When someone would ask the high priest a question of Torah, or Jewish law, the high priest could invoke the Name, wherein the 12 jewels, representing the 12 tribes of the Israelites, would light up in a certain order whose meaning was, too, only known to the high priest. Through the power of the 72-letter name of God, the high priest communed, as it were, with the Almighty.

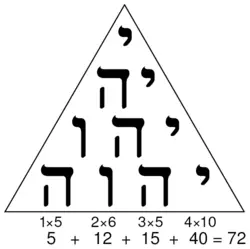

Why 72 letters? The answer may be found in the medieval rabbinic use of Gematria, that is assigning a number to each letter of the Hebrew alphabet, allowing scholars to attribute numeric sums to words, find equivalencies in certain words, even use sums to try to predict a year and date for the coming of the Messiah. Even today, Jews often attribute mystical significance to the number 18, which has a possible Hebrew letter equivalent in the word "Chai", meaning "Life". Using "Gematria", we find that "Chai" equals 18: it's composed of the letter "chet", which equals 8, and the letter "yod", which equals 10, i.e. 8+10=18; consequently 18x4=72, so, in a sense, each letter of the 4-letter form of the Name represents a metaphoric symbol of the living power of God. Also, when the letters of the Tetragrammaton are arranged in a Kabbalistic tetractys formation, the sum of all the letters is 72 by Gematria (as shown in the diagram). Keeping along these lines, the Tetragrammaton, since it's only an abbreviation of the actual name, is not as powerful by nature (or supernature) as the original full name of God, though it's still not something to use in vain.

When most religious Jews refer to the name of God in conversation or in a non-textual context such as in a book, newspaper or letter, they call the name HaShem, which means "the Name." Similarly, the word Elohim is prononuced "Elokim" outside of certain religious contexts when it refers to God, and likewise for a few other names of God. When any such word is used to refer to anything but God (e.g., HaShem), it is pronounced as normal by even the most traditionalist Jews.

A number of modern translations of the Hebrew Bible and of Jewish liturgy render the Tetragrammaton as "the ETERNAL" (emphasized or all caps), because it is gender-neutral (unlike "The Lord"). The Hebrew letters of the Tetragrammaton are the only ones required to write the Hebrew sentence "haya, hove, ve-yiheyeh" (He was, He is, and He shall be), hence "Eternal."

Attributes

Assuming that Yahweh was primitively a nature god, scholars in the 19th century discussed the question over what sphere of nature he originally presided. According to some he was the god of consuming fire; others saw in him the bright sky, or the heaven; still others recognized in him a storm god, a theory with which the derivation of the name from Hebrew hawah or Arabic bawd well accords. The association of Yahweh with storm and fire is frequent in the Old Testament; the thunder is the voice of Yahweh, the lightning his arrows, the rainbow his bow. The revelation at Sinai is amid the awe-inspiring phenomena of tempests. Yahweh leads Israel through the desert in a pillar of cloud and fire; he kindles Elijah's altar by lightning, and translates the prophet in a chariot of fire. See also Judg. v. 4 seq.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

See a collection and critical estimate of this evidence by Zimmern, Die Keilinschriften und das Alte Testament, 465 seq.

1. Babel and Bibel, 1902. The enormous, and for the most part ephemeral, literature provoked by Delitzschs lecture cannot be cited here.

2. Denkschriften d. Wien. Akad., L. iv. p. 115 seq. (1904).

3. Wolagdas Paradies (1881), pp. 158-166.

Footnotes

- 1. Galatin, Peter - De Arcanis Catholicæ Veritatis, 1518, folio xliii

- 2. See pages 128 and 236 of the book "Who Were the Early Israelites?" by archeologist William G. Dever, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, 2003.

- 3.Wilhelm Gesenius is noted for being one of the greatest Hebrew and biblical scholars.

- 4. Wilhelm Gesenius' Hebrew Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament was first translated into English in 1824,

- 5. Smith's "A Dictionary of the Bible"

- 6. Encyclopedia Britannica of 1910-1911 Page 312

- 7.Smith's "A Dictionary of the Bible": Clement of Alexandria wrote "Iaou" not "Iaoue" at Stromata Book V.

- 8. Smith's "A Dictionary of the Bible": Yahweh supposed to have been derived from Samaritan "IaBe"

- 9. The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1910 under the sub-heading: To take up the ancient writers

- 10. The online Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901-1906

External links

- Arbel, Ilil. "Yahweh." Encyclopedia Mythica. 2004.

- "Jehovah." Easton's Bible Dictionary (3rd ed.) 1887.

- "Jehovah (Yahweh)." Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume 8. 1910.

- Jewish Encyclopedia count of number of times the Tetragrammation is used

- Nazarenes and the Name of YHWH, an article by James Trimm

- The Historical Evolution of the Hebrew God

- The Rise of God

- The Sacred Name Yahweh, a publication by Qadesh La Yahweh Press

- Biblaridion magazine: Phanerosis Theology: The Tetragrammaton and God's manifestation.

- HaVaYaH the Tetragrammation in the Jewish Knowledge Base on chabad.org

- Titles of Deity, a Christadelphian view

- YHWH/YHVH — Tetragrammaton

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.