Wounded Knee, South Dakota

| Wounded Knee, South Dakota | |

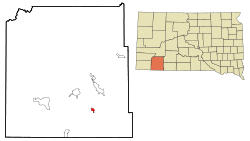

| Location in Shannon County and the state of South Dakota | |

| Coordinates: {{#invoke:Coordinates|coord}}{{#coordinates:43|8|38|N|102|22|4|W|type:city | |

|---|---|

| name= }} | |

| Country | United States |

| State | South Dakota |

| County | Shannon |

| Area | |

| - Total | 1.1 sq mi (2.8 km²) |

| - Land | 1.1 sq mi (2.8 km²) |

| - Water | 0 sq mi (0 km²) |

| Elevation | 3,235 ft (986 m) |

| Population (2000) | |

| - Total | 328 |

| - Density | 298.2/sq mi (117.1/km²) |

| Time zone | Mountain (MST) (UTC-7) |

| - Summer (DST) | MDT (UTC-6) |

| ZIP code | 57794 |

| Area code(s) | 605 |

| FIPS code | 46-72900GR2 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1265714GR3 |

Wounded Knee (Lakota language: Chankwe Opi) is a small town in Shannon County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 328 in the 2000 census. It is named for the Wounded Knee Creek, a tributary of the White River, which runs through the region.

Wounded Knee Creek rises in the southeastern corner of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation along the state line with Nebraska and flows northwest, past the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre and the towns of Wounded Knee and Manderson. It flows north-northwest across the reservation and joins the White River south of Badlands National Park. The bones and heart of the Sioux chief Crazy Horse were reputedly buried along this creek by his family following his assassination in 1877.

Wounded Knee was the site of two major incidents in the historical conflict between Native Americans and white Americans. The first was the Wounded Knee Massacre, the last major armed conflict between the Lakota Sioux and the United States, subsequently described as a "massacre" by General Nelson A. Miles in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. The second event, commonly known as the Wounded Knee Incident took place in February 1973 when the town was seized and occupied by the American Indian Movement (AIM). They were protesting the reservation’s president, whom they accused of misuse of funds and of authority.

Wounded Knee massacre

| Wounded Knee massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sioux Wars | |||||||

Miniconjou Chief Big Foot lies dead in the snow | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Sioux | United States | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Big Foot† | James W. Forsyth | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 120 men

230 women and children |

500 men | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 153 killed

50 wounded 150 missing |

25 killed

39 wounded | ||||||

Prelude

The Sioux controlled the northern Plains, including the Black Hills, throughout most of the nineteenth century. A series of treaties with the U.S. Government were entered into by the Allied Lakota bands at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, in 1851 and 1868. The terms of the treaty of 1868 specified the area of the Great Sioux Reservation to be all of South Dakota west of the Missouri River and additional territory in adjoining states and was to be

- "set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation" of the Lakota. [1] Further, "No white person or persons shall be permited to settle upon or occupy any portion of the territory, or without the consent of the Indians to pass through the same." [2]

Although whites were to be excluded from the reservation, after the public discovery of gold in the 1870s, the conflict over control of the region sparked the last major Indian War on the Great Plains, the Black Hills War. Yielding to the demands of prospectors, in 1874 the U.S. government dispatched troops into the Black Hills under General George Armstrong Custer in order to establish army posts. During the 1875–1878 gold rush, thousands of miners went to the Black Hills; in 1880, the area was the most densely populated part of Dakota Territory. The Sioux responded to this intrusion militarily.

The government had offered to purchase the land from the Tribe, but considering it sacred, they refused to sell. In response, the government demanded that all Indians who left the reservation area (mainly to hunt buffalo) report to their agents; few complied. The U.S. Army did not keep miners off Sioux hunting grounds; yet, when ordered to take action against bands of Sioux hunting on the range, according to their treaty rights, the Army moved vigorously.

On June 25, 1876, after several indecisive encounters, General Custer found the main encampment of the Lakota and their allies at the Little Bighorn River in eastern Montana. Custer and his men — who were separated from their main body of troops — were all killed by the far more numerous Indians who had the tactical advantage. They were led in the field by Crazy Horse and inspired by Sitting Bull's earlier vision of victory. This has come to be known as the "Battle of the Little Bighorn".

Outraged, the U.S. took control of the region from the Lakota in violation of the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868). In 1877, the year after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Congress passed legislation that opened the Black Hills to white occupation. Under the terms of the new treaty, the Sioux were forced to cede the Black Hills for a fraction of their value, and the area was opened to the gold miners.

By 1889, the situation on the reservations was getting desperate. In February 1890, the U.S. government unilaterally divided the Great Sioux Reservation into five smaller reservations. This was done to accommodate white homesteaders from the eastern part of the country, even though it broke the terms of the treaty. Once settled on the reduced reservations, tribes were separated into family units on 320-acre plots and forced to farm and raise livestock.

To help support the Sioux during the period of transition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), was delegated the responsibility of supplementing the Sioux economy with food distributions and hiring white farmers as teachers for the people. The farming plan failed to take into account the difficulty Sioux farmers would have in trying to cultivate crops in the semi-arid region of South Dakota. By the end of the 1890 growing season, a time of intense heat and low rainfall, it was clear that the land was unable to produce substantial agricultural yields. Unfortunately, this was also the time when the government’s patience with supporting the Indians ran out, resulting in rations to the Sioux being cut in half. With the bison virtually eradicated from the plains a few years earlier, the Sioux had few options available to escape starvation.

Ghost Dance

A Paiute mystic by the name of Wovoka gained a reputation as a powerful shaman early in adulthood and was known as a gifted young leader. He often presided over circle dances, while preaching a message of universal love. At about the age of thirty, he began to weave together various cultural strains into the Ghost Dance religion. The beliefs were incorporated from those of a number of Native visionaries seeking relief from the hardships that accompanied the spreading white civilization, as well as from his earlier immersion into Christianity.

Wovoka reported a vision he experienced during a solar eclipse on January 1, 1889. According the report of Anthropologist James Mooney, who conducted an interview with Wovoka in 1892, he had stood before God in Heaven, and had seen many of his ancestors engaged in their favorite pastimes. God showed him a beautiful land filled with wild game, and instructed him to return home to tell his people that they must love each other, not fight, and live in peace with the whites. God also stated that Wilson's people must work, not steal or lie, and that they must not engage in the old practices of war or the self-mutilation traditions connected with mourning the dead. God said that if his people kept by these rules, they would be united with their friends and family in the other world.

He was then given the formula for the proper conduct of the Ghost Dance — a form of circle dance practiced for centuries by many native tribes — and commanded to bring it back to his people. Wilson preached that if this five-day dance was performed in the proper intervals, the performers would secure their happiness and hasten the reunion of the living and deceased. Wovoka claimed to have left the presence of God convinced that if every Indian in the West danced the new dance to “hasten the event,” all evil in the world would be swept away leaving a renewed Earth filled with food, love, and faith. Quickly accepted by his Paiute brethren, the new religion was termed “Dance In A Circle."

Wovoka prophesied an end to white American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and peace between whites and Indians. The practice swept throughout much of the American West, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As it spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selected aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs, creating changes in both the society that integrated it and the ritual itself. Because the first white contact with the practice came by way of the Sioux, their expression "Spirit Dance" was adopted as a descriptive title for all such practices. This was subsequently translated as "Ghost Dance."

Although Ghost Dancing was a spiritual ceremony, the agents may have misinterpreted it as a war dance. In any case, fearing that the ghost dance philosophy signaled an Indian uprising, many agents outlawed it. In October 1890, believing that a renewal of the earth would take place in the coming spring, the Lakota of Pine Ridge and Rosebud defied their agents and continued to hold dance rituals. Lakota delegations to Wovoka's Paiute reserve had reinterpreted Wovoka's message to suggest that the whites would disappear and that the renewed earth would be for Indians alone (Mooney, p. 820). Lakota ghost dancers wore ghost shirts, specially consecrated garments which they believed rendered them impervious to harm. Devotees were dancing to pitches of excitement that frightened the government employees, setting off a panic among white settlers. Pine Ridge agent Daniel F. Royer then called for military help to restore order and subdue the frenzy among white settlers.

Big Foot

On December 15, an event occurred that set off a chain reaction ending in the massacre at Wounded Knee. Chief Sitting Bull was killed at his cabin on the Standing Rock Reservation by Indian police who were trying to arrest him on government orders. Sitting Bull was one of the Lakota’s tribal leaders, and after his death, refugees from Sitting Bull’s tribe fled in fear. They joined Sitting Bull's half brother, Big Foot, at a reservation at Cheyenne River. Unaware that Big Foot had renounced the Ghost Dance, General Nelson A. Miles ordered him to move his people to a nearby fort. On December 28, 1890, Big Foot became seriously ill with pneumonia. His tribe then set off to seek shelter with Chief Red Cloud at Pine Ridge reservation. Big Foot’s band was intercepted by Major Samuel Whitside and his battalion of the Seventh Cavalry Regiment and were escorted five miles westward to Wounded Knee Creek. There, Colonel James W. Forsyth arrived to take command and ordered his guards to place four Hotchkiss guns in position around the camp. The soldiers numbered around 500—the Indians, 350; all but 120 were women and children. A rumor among the Lakota during the evening of December 28, 1890, said that all Indians were to be deported to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) which had the reputation for living conditions far worse than any prison. The Lakota became fearful that the rumor was true. The interpreter was not fluent in the peculiar dialect of Hohwoju used by Big Foot's people, and he mistranslated the Indians' speeches making them appear more belligerent than they actually were.[3] Eyewitness accounts also claimed that the soldiers had been drinking and celebrating the capture of Big Foot.

Battle

On December 29, the Lakota were informed that it was necessary to turn in any weapons they possessed to prevent violence. A search was ordered, which turned up a few weapons. A medicine man called Yellow Bird began to perform the ghost dance, reminding the Lakota that the ghost shirts were bullet-proof. As tension mounted, a scuffle broke out between a soldier trying to disarm a deaf Indian named Black Coyote. He had not heard the order to turn in his gun and assumed he was being charged with theft. At that moment, a firearm discharged, and at the same moment Yellow Bird threw some dust into the air. Indian bystanders said he meant it as a ceremonial gesture but the hairtriggered soldiers took it for a signal to attack. The silence of the morning was broken by the guns echoing near the river bed. At first, the struggle was fought at close range, but when the Indians ran to take cover, the Hotchkiss cannons started shooting and shredding tipis. A few Lakota were able to produce concealed weapons.

By the end of fighting, which lasted less than an hour, 153 Lakota had been killed and 50 wounded. These numbers are under reported, in actuality the Lakota dead numbered as many as 300 or more. In comparison, army casualties numbered 25 dead and 39 wounded. Forsyth was later charged with the killing of innocents but was exonerated.

It is claimed that while the soldiers were firing at the Lakota they were yelling repeatedly “Remember the Little Bighorn,” or “Remember Custer.” After the shooting stopped, U.S army officials gathered up their dead and wounded soldiers, some of whom died later. Some had been caught in friendly crossfire. Soldiers stripped the bodies of the dead Lakota, keeping their ghost shirts and other clothing and equipment as souvenirs.

The first was the Wounded Knee Massacre, the last major armed conflict between the Dakota Sioux and the United States, subsequently described as a "massacre" by General Nelson A. Miles in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. [4] On December 29, 1890, five hundred troops of the U.S. 7th Cavalry, supported by four Hotchkiss guns (a lightweight artillery piece capable of rapid fire), surrounded an encampment of Miniconjou Sioux (Lakota) and Hunkpapa Sioux (Lakota)[5] with orders to escort them to the railroad for transport to Omaha, Nebraska. The commander of the 7th had been ordered to disarm the Lakota before proceeding and placed his men in too close proximity to the Lakota, alarming them. Shooting broke out near the end of the disarmament, and accounts differ regarding who fired first and why.

By the time it was over, 25 troopers and 300 Lakota Sioux lay dead, including men, women, and children. Many of the dead soldiers are believed to have been the victims of "friendly fire" as the shooting took place at point blank range in chaotic conditions, and most of the Lakota had previously been disarmed.[6] Around 150 Lakota are believed to have fled the chaos, of which many likely died from exposure.

Aftermath

The military hired civilians to bury the dead Lakota after an intervening snowstorm had abated. Arriving at the battleground, the burial party found the deceased frozen in contorted positions by the freezing weather. They were gathered up and placed in a common grave. It was reported that four infants were found still alive, wrapped in their deceased mothers' shawls. In all, 84 men, 44 women, and 18 children died on the field, while at least seven of Lakota were mortally wounded. These numbers are under reported, in actuality the Lakota dead numbered as many as 300 or more.

Colonel Forsyth was immediately denounced by General Nelson Miles and relieved of command. An exhaustive Army Court of Inquiry convened by Miles criticized Forsyth for his tactical dispositions but otherwise exonerated him of responsibility. The Court of Inquiry, however—while it did include several cases of personal testimony pointing toward misconduct—was flawed[citation needed]. It was not conducted as a formal court-martial, and without the legal boundaries of that format, several of the witnesses minimized their comments and statements to protect themselves or peers[citation needed]. Ultimately the Secretary of War concurred and reinstated Forsyth to command of the 7th. Testimony before the court indicated that for the most part troopers attempted to avoid non-combatant casualties. Nevertheless Miles ignored the results of the Court of Inquiry and continued to criticize Forsyth, whom he believed had deliberately disobeyed orders. The concept of Wounded Knee as a deliberate massacre rather than a tragedy caused by poor decisions stems from Miles[citation needed].

The American public's reaction to the battle was at the time generally favorable. Twenty Medals of Honor were awarded for the action. A decade later when these were reviewed, Miles saw that they were retained. Currently, Native Americans are urgently seeking the recall of what they refer to as "Medals of Dis-Honor." Many non-Lakota living near the reservations interpreted the battle as a defeat of a murderous cult, though some confused Ghost Dancers with Native Americans in general. In an editorial in response to the event, a young newspaper editor, L. Frank Baum (later known as the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz), wrote in the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer on January 3, 1891:

"The Pioneer has before declared that our only safety depends upon the total extermination of the Indians. Having wronged them for centuries, we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth. In this lies future safety for our settlers and the soldiers who are under incompetent commands. Otherwise, we may expect future years to be as full of trouble with the redskins as those have been in the past." [1]

Skirmish at Drexel Mission

Historically, Wounded Knee is generally considered to be the end of the Indian Wars, the collective multi-century series of conflicts between colonial and U.S. forces and American Indian peoples. It was also responsible for the subsequent severe decline in the Ghost Dance movement.

However, it was not the last armed conflict between Native Americans and the United States.

A related skirmish took place at Drexel Mission the day after the Battle of Wounded Knee that resulted in the death of one trooper and the wounding of six others from K Troop, 7th Cavalry, with an unknown number of Lakota casualties. Lakota Ghost Dancers from the bands which had been persuaded to surrender had fled after news of Wounded Knee reached them, and they burned several buildings at the mission. They ambushed a squadron of the 7th Cavalry responding to the incident and pinned it down until a relief force from the 9th Cavalry arrived. It had been trailing the Lakota from the White River. Lieutenant James D. Mann, who had been a key participant in the outbreak of firing at Wounded Knee, died of his wounds 17 days later at Ft. Riley, Kansas on January 15, 1891. This engagement is often overlooked, being overshadowed by the previous day's tragedy.

Wounded Knee Incident, 1973

The Wounded Knee incident began February 27, 1973 when the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota was seized by followers of AIM (the American Indian Movement). The occupiers controlled the town for 71 days while the U.S. Marshals Service laid siege.

Background

Wounded Knee is a town on the Pine Ridge Reservation and home to the Oglala Sioux Indians.[7] The area is historically significant as in 1890 it was the setting for a U.S. military massacre of approximately 146 Native Americans (the number of people killed is imprecise because the military at the time did not count the exact number of deaths).[7] The 1973 incident erupted for many reasons but mainly due to the opposition of the reservation’s president, Richard "Dick" Wilson. Opponents of Wilson accused him of:

- "Mishandling tribal funds"[7]

- Abuse of his authority; AIM cites the U.S. Commission of Civil Rights alleging that Wilson’s election had been "permeated with fraud"[8]

- Using "brute force" for political means such as his private army the GOON’s (Guardians of the Oglala Nation) that AIM labeled as Wilson’s "official terrorist 'goon squad'"[9]

His opponents also unsuccessfully attempted to impeach him in 1973.[7] In fact, over 150 civil rights complaints had been issued against the reservation government in the years prior to the incident.[10] AIM claims they chose Wounded Knee because of its historical significance. They considered the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre "a prime example of the treatment of Indians since the European invasion".[9]

OSCRO (the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization) was an organization on the Pine Ridge Reservation that attempted to change the poor civil conditions. A meeting was held on February 26, 1973 "to openly discuss their grievances concerning the tribal government".[9] Another meeting was held the next day, February 27 and AIM was summoned "for some assistance," by OSCRO to produce "results".[9] Dennis Banks states that it was "the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization which called upon [AIM], and we responded".[11] AIM was a national Indian rights organization largely considered an urban, "red power" movement; the group was led by Dennis Banks and, at Wounded Knee, Russell Means.[12] The government (Nixon administration) was wary of the perceived militant organization. In fact, the Department of Justice requested that the FBI "intensify its efforts in identifying violence-prone individuals" in AIM.[12] Between 200 and 300 AIM members entered the town on February 26. An official, reliable count of AIM members entering or occupying the town was never recorded and would have been difficult to achieve, but AIM claims that approximately 300 members of their organization entered the village while the government estimates 200.[9][13]

Occupation

On February 27 the AIM and Oglala Sioux (or those opposed Wilson) seized the town of Wounded Knee; the U.S. military and government began their siege of Wounded Knee the same day.[14] It is disputed whether the government forces cordoned the town before, as AIM claims, or after the takeover. According to former South Dakota Senator James Abourezk,[7][15] "on 25 February 1973 the U.S. Department of Justice sent out 50 U.S. Marshals to the Pine Ridge Reservation to be available in the case of a civil disturbance".[7] AIM, on the other hand, argues that their organization came to the town for an open meeting and "within hours police had set up roadblocks, cordoned off the area and began arresting people leaving town… the people prepared to defend themselves against the government’s aggressions".[9] Regardless, by the morning of February 28, both sides were firmly entrenched.

Both AIM and government documents show that the two sides traded fire for most of the three months.[9][14] John Sayer, a Wounded Knee chronicler claims that:[16]

- "The equipment maintained by the military while in use during the siege included fifteen armored personal carriers, clothing, rifles, grenade launchers, flares, and 133,000 rounds of ammunition, for a total cost, including the use of maintenance personnel from the national guard of five states and pilot and planes for aerial photographs, of over half a million dollars"

The statistics gathered by Record and Hocker largely concur:[11]

- "...barricades of paramilitary personnel armed with automatic weapons, snipers, helicopters, armored personnel carriers equipped with .50-caliber machine guns, and more than 130,000 rounds of ammunition".

The precise statistics of U.S. government force at Wounded Knee vary, but all accounts agree that it was certainly a significant military force including "federal marshals, FBI agents, and armored vehicles." One eye witness and journalist chronicled, "sniper fire from…federal helicopters," "bullets dancing around in the dirt" and "sounds of shooting all over town" [from both sides].[17] AIM claims in its chronology of the occupation that "the government tried starving out the [occupants]" and that they, the occupiers, smuggled food and medical supplies in past roadblocks "set up by Dick Wilson and tacitly supported by the government".[9]

In the course of the conflict, Frank Clearwater, a Wounded Knee occupier, was shot in the head while asleep on April 17 and died on April 25.[7] Lawrence Lamont, also an occupier, received a fatal gunshot wound on April 26, and U.S. Marshal Lloyd Grimm was paralyzed from the waist down again by a gunshot wound.[7]

Both sides reached an agreement on May 5 to disarm.[7][9] By May 8 the siege had ended and the town was evacuated after 71 days of occupation; the government then took control of the village.[7][9]

AIM conspiracy and abuse allegations

AIM alleges that the United States government restricted their freedom of press and thus tried to manipulate the media to an anti-AIM position. AIM claims "communications were cut for over a month and the press was prevented from first-hand information" and that their "freedom of press was obstructed throughout the liberation".[9] AIM documents also claim that after the U.S. government forces seized the town of Wounded Knee, they "caused massive destruction of personal property and homes".[9]

Possible: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonard_Peltier

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

Dee Brown's Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, first published in 1970, is a history of Native Americans in the American West in the late nineteenth century, and their displacement and slaughter by the United States federal government. Chapter by chapter, this book moves from tribe to tribe of Native Americans, and outlines the relations of the tribes to the U.S. federal government during the years 1860-1890. It begins with the Navajos, the Apaches, and the other tribes of the American Southwest who were displaced as California and the surrounding states were settled. Brown chronicles the changing and sometimes conflicting attitudes both of American authorities such as General Custer and Indian chiefs, particularly Geronimo, Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and Crazy Horse, and their different attempts to save their peoples, by peace, war, or retreat. The later part of the book focuses primarily on the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes of the plains, who were among the last to be moved onto reservations, under perhaps the most violent circumstances. It culminates with the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the murders of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, and the slaughter of Sioux prisoners at Wounded Knee, South Dakota that is generally considered the end of the Indian Wars. One strength of the book is its strong documentation of original sources.[18] Its message may not have been a welcome one, but it is backed with sources and references. It remained on best seller lists for over a year, and was still in print 35 years later. Bury my heart at Wounded Knee is the final phrase of a 20th-century poem titled "American Names" by Stephen Vincent Benet. (The poem was not actually about the Indian wars.) The full quotation, "I shall not be here/I shall rise and pass/Bury my heart at Wounded Knee," appears at the beginning of Brown's book.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ US History Encyclopedia. 2006. United States v. Sioux Nation Answers Corporation. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ↑ Brown, Dee. 1970. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Owl Books: Henry Holt. page 273. ISBN 0805010459

- ↑ Flood, Renee S., Lost Bird of Wounded Knee, Da Capo Press 1998

- ↑ Letter: General Nelson A. Miles to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, March 13, 1917.

- ↑ Liggett, Lorie (1998). The Wounded Knee Massacre - An Introduction. Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 2007-03-02.

- ↑ Strom, Karen (1995). The Massacre at Wounded Knee. Karen Strom.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Abourezk, James G. Wounded Knee, 1973 Series. - University of South Dakota, Special Collections Website. Retrieved May 10, 2007

- ↑ Wounded Knee Support Committee. WKSC News, 1-4. - Retrieved on May 10, 2007

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 Wounded Knee Information Booklet. American Indian Movement. pp 10-18. Retrieved May 10, 2007

- ↑ Morris, R., Sanchez, J., & Stuckey, M. (1999). Rhetorical Exclusion: The Government's Case Against American Indian Activists, AIM, and Leonard Peltier [Electronic version]. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 23(2), 27-55.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Record, I. & Hocker, A. P. (1998). A Fire that Burns: The Legacy of Wounded Knee. Native Americas, 15(1), 14. Retrieved May 10, 2007 from ProQuest

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Kotlowski, D. J. (2003). Alcatraz, Wounded Knee, and Beyond: The Nixon and Ford Administrations Respond to Native American Protest [Electronic version]. Pacific Historical Review, 72(2), 201-227.

- ↑ This Month in History: February. - United States Departmental Office of Civil Rights. - Retrieved May 10, 2007

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Wounded Knee Incident". - United States Marshal Services. - Retrieved May 10, 2007

- ↑ James G. Abourezk was a Senator at the time of Wounded Knee. He was present at the conflict and even entered the AIM (and Wilson opposition) occupied town. Abourezk is also a chronicler of the 1973 incident and has conducted hearings under the "authority of U.S. Senate Subcommittee of Indian Affairs"

- ↑ Sayer, J. (1997). Ghost Dancing the law: The Wounded Knee trials. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ McKiernan, K. Barry. "Notes from a Day at Wounded Knee". - Retrieved May 10, 2007

- ↑ Momaday, N. Scott, "A History of the Indians of the United States", New York Times, 1971-03-07, p. BR46.

Further reading

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West, Owl Books (1970). ISBN 0-8050-6669-1.

- Coleman, William S.E. Voices of Wounded Knee, University of Nebraska Press (2000). ISBN 0-8032-1506-1.

- Smith, Rex Alan. Moon of Popping Trees, University of Nebraska Press (1981). ISBN 0-8032-9120-5.

- Utley, Robert M. Last Days of the Sioux Nation, Yale University Press (1963).

- Utley, Robert M. The Indian Frontier 1846-1890, University of New Mexico Press (2003). ISBN 0-8263-2998-5.

- Utley, Robert M. Frontier Regulars The United States Army and the Indian 1866-1891, MacMillan Publishing (1973).

- Yenne, Bill. Indian Wars: The Campaign for the American West, Westholme (2005). ISBN 1-59416-016-3.

- Champlin, Tim. A Trail To Wounded Knee : A Western Story, Five Star (2001). ISBN 0-7826-2401-0

External links

All Links Retrieved December 10, 2007.

- The Wounded Knee Museum in Wall, South Dakota

- Read a review of HBO's Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee

- Bureau of American Ethnology report on the Ghost Dance Religion

- Editorials by L. Frank Baum

- History of the Ghost Dance Religion

- PBS biography of Jack Wilson

- Walter Mason camp collection includes photographs from the Wounded Knee Massacre

- The Lost Bird of Wounded Knee (1890-1920)

- US Army Casuality list of Wounded Knee

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Wounded_Knee_Massacre history

- Wounded_Knee_incident history

- Wounded_Knee_South_Dakota history

- Bury_My_Heart_at_Wounded_Knee history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.