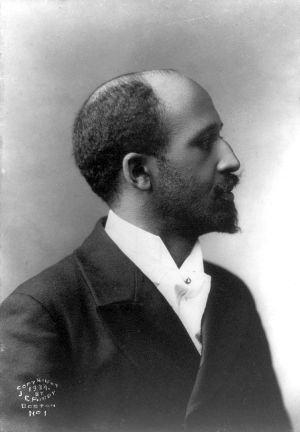

W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (International Phonetic Alphabet|pronounced [du'bojz]) (February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was a civil rights activist, a sociologist, and an educator, who is widely recognized as the foremost black intellectual and the principal black protest spokesperson during the first half of the 20th century. His achievements as a scholar, prolific writer, editor, poet, and historian earned him the honor, in 1943, of being the first black admitted to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1963, at the age of 95, he became a naturalized citizen of Ghana, renouncing his American citizenship, and choosing to live his final days as a self-exiled Communist.

The post-Reconstruction-Era U.S.A. was rife with such ills as Jim Crow segregation laws, lynchings, peonage, race riots and disfranchisement, all of which evinced a context of intensely noxious racism. Prior to his graduation, at age 20, from Fisk University, one of the premiere black institutions of higher learning, the young Du Bois had already resolved to take up the mission of liberating black America from oppression. He envisioned himself as a destined race leader. And since his background was quite different from that of Booker T. Washington, Du Bois ultimately developed a different perspective regarding what had to be done to bring about racial reconciliation. David Levering Lewis, his acclaimed biographer, wrote: "In the course of his long, distinguished career, W.E.B. Du Bois attempted virtually every possible solution to the problem of 20th-century racism—scholarship, propaganda, integration, cultural and economic separatism, politics, international communism, expatriation, and third world solidarity." [W.E.B. Du Bois—The Fight for Equality and the American Century: 1919-1963]

Biography

Born at Church Street, on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, W.E.B. Du Bois was the son of Alfred Du Bois and Mary Silvina Burghardt Du Bois. The couple's February 5, 1867 wedding had been announced in the Berkshire Courier. Alfred Du Bois was born in San Domingo, Haiti [David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868-1919]. His son was born one year after the ratification and addition of the Fourteenth Amendment [1] to the U.S. Constitution. Alfred Du Bois, himself, was descended from free people of color, and he could trace his lineage back to one Dr. James Du Bois of Poughkeepsie, New York. This physician, while in the Bahamas, had sired three sons, including Alfred, along with a daughter, by his slave mistress.

In 1890, two years ater receiving his Bachelor's degree from Fisk University, Du Bois graduated cum laude, with a Master's degree from Harvard University. He then went abroad to study at the University of Berlin. In 1894, at the age of twenty-six, he returned to America and taught at Wilberforce University. The next year, Du Bois became the first black person to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University. This advanced degree was in history, despite the fact that Du Bois's primary training was in the social sciences. His doctoral dissertation, The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870 (1896), was a foretaste of the type of observational investigations and case studies he would produce in the years to come. Following his professorship at Wilberforce, he taught at the University of Pennsylvania, where he published the trailblazing sociological study, The Philadelphia Negro (1899). He then went on to Atlanta University, where he established the first department of sociology in the United States, and where he systematized a sequence of studies exploring the life and history of American blacks. [2]

Steeped in academia, research, and publication, Du Bois was intially passionate in his conviction that, through social science, the knowledge to resolve the race problem would be found. In addition, he firmly believed that a college degree was essential, since it furnished young blacks with the insight and intellectual competency required to be of service to the race. Ultimately, however, the steadily worsening racial climate of his day drove him gradually to the conclusion that only through agitation and protest could genuine social transformation be wrought.

A diligent seeker of truth, Du Bois spent the period from 1910-1934 on leave from his Atlanta University professorship, as he explored one potential method after another for solving the intractable race crisis. He had become quite exasperated over the fact that his several sociological publications had been given virtually no notice by influential opinion molders. And he seethed over the idea that, in his view, the leadership of Booker T. Washington and his Tuskegee Machine enabled the hated caste system to remain in place, and kept black America beneath the heel of accomodation to white supremacy.

After Washington's death in 1915, Du Bois was heartened by the prospect that he would no longer be hindered by a leadership struggle with the Tuskegeean. By the following year, Du Bois had replaced Washington as America's most prominent black leader. From 1916-1930, increasing numbers of blacks were embracing the Atlanta professor's doctrine of advancement through protest and agitation. Yet, as he and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) shifted from black America's "radical" fringe to the centrist position, Du Bois often found himself necessarily encouraging the same tactics for which he had opposed Washington. And, in response, ironically, heaped upon Du Bois were the same criticisms he had wreaked upon his old rival. His most satisfying experience of this period, however, was his reign as editor of the Crisis magazine, which he employed as a forum to promote philosophical debate, race-issue-related commentary, cultural nationalism, and a host of other concerns that he deemed significant.

The Atlanta professor's attraction to Socialism and Marxism increased throughout the 1920s. During a 1926 visit to the Soviet Union, he stated, "If what I've seen with my eyes and heard with my ears in Russia is Bolshevism, then I am a Bolshevik." This statement was evidence of a profound change of heart and direction. That shift had come about as a result of Du Bois's connections to early Socialists like Charles E. Russell, Mary White Ovington, William E. Walling, and Joel E. Spingarn, who were the gound-floor architects of the N.A.A.C.P. By 1934, Du Bois had resigned as editor of the Crisis, and had resumed his professorship at Atlanta University. His years of having conflicted with N.A.A.C.P. Executive Secretary Walter White had left Du Bois frustrated. In addition, he was greatly disillusioned over the fact that his idea of a nationalist Pan-African Movement had fallen on deaf ears. Too, his theory of The Talented Tenth, as black America's most exemplary elite, who would embody the intelligence and the competency needed to pull the entire race up to full citizenship, had found few takers.

By the mid-1930s, Du Bois's ties with the ideological Left had brought him some serious problems. His crusades for "voluntary segregation" and "economic separatism" triggered aspersions from other intellectuals. As he increasingly identified himself with pro-Marxist causes, he attracted the watchful eye of the federal government. Indicted and acquitted in 1951 of charges that he was a subversive agent of a foreign government, he became totally disillusioned with America. In a 1961 letter to Gus Hall, Du Bois wrote, "Today I have reached a firm conclusion that Capitalism cannot reform itself. It is doomed to self destruction. No universal selfishness can bring social good to all. Communism...is the only way of human life." Two years later, in Ghana, as a card-carrying Communist, Du Bois died.

Life's Work

Civil Rights Activism

In 1895, from his teaching post at Wilberforce University, the young Du Bois joined the throng of Americans around the country who congratulated Booker T. Washington on his landmark Atlanta Exposition Address. At that point, Du Bois agreed with Washington that fervent faith in God, strong families, and hard work were indispensable for human advancement. Eight years later, however, Du Bois openly attacked Washington, denouncing him and his program as hindrances to authentic black advancement, and insisting that the Washingtonian approach would not serve the long-term interests of blacks as a whole:

While prominent white voices decried African American cultural, political and social relevance to American history and civic life, in his epic work, Reconstruction Du Bois documented how black people were the central figures in the American Civil War and Reconstruction. He demonstrated the ways Black emancipation—the crux of Reconstruction—promoted a radical restructuring of United States society, as well as how and why the country turned its back on human rights for African Americans in the aftermath of Reconstruction.[3] This theme was taken up later and expanded by Eric Foner and Leon F. Litwack, the two leading contemporary scholars of the Reconstruction era.

Civil Rights Activism

Du Bois was the most prominent intellectual leader and political activist on behalf of African Americans in the first half of the twentieth century. A contemporary of Booker T. Washington, the two carried on a dialogue about segregation and political disenfranchisement. Labeled the "father of Pan-Africanism", Du Bois believed that people of African descent should work together to battle prejudice and inequality.

In 1905, Du Bois helped to found the Niagara Movement with William Monroe Trotter but their alliance was short-lived as they had a dispute over whether or not white people should be included in the organization and in the struggle for Civil Rights. Du Bois felt that they should, and with a group of like-minded supporters, he helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

In 1910, he left his teaching post at Atlanta University to work as publications director at the NAACP full-time. He wrote weekly columns in many newspapers, including the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier and the New York Amsterdam News, three African-American newspapers, and also the Hearst-owned San Francisco Chronicle.

For 25 years, Du Bois worked as Editor-in-Chief of the NAACP publication, The Crisis, which then included the subtitle A Record of the Darker Races. He commented freely and widely on current events and set the agenda for the fledgling NAACP. Its circulation soared from 1,000 in 1910 to more than 100,000 by 1920. [The Baltimore Sun, June 8, 1997, "A New and Changed NAACP Magazine"]

Du Bois published Harlem Renaissance writers Langston Hughes and Jean Toomer. As a repository of black thought, the Crisis was initially a monopoly, David Levering Lewis observed. In 1913, Du Bois wrote The Star of Ethiopia, a historical pageant, to promote African-American history and civil rights.

The seminal debate between Booker T. Washington and Du BoisTemplate:Cite needed played out in the pages of the Crisis with Washington advocating an accommodational philosophy of self-help and vocational training for Southern blacks while Du Bois pressed for full educational opportunities.

Du Bois became increasingly estranged from Walter Francis White, the executive secretary of the NAACP, and began to question the organization's opposition to racial segregation at all costs. Du Bois thought that this policy, while generally sound, undermined those black institutions that did exist, which Du Bois thought should be defended and improved, rather than attacked as inferior. By the 1930s, Lewis said, the NAACP had become more institutional and Du Bois, increasingly radical, sometimes at odds with leaders such as Walter White and Roy Wilkins. In 1934, after writing two essays in the Crisis suggesting that black separatism could be a useful economic strategy, Du Bois left the magazine to return to teaching at Atlanta University.

White Historians

In 1899, the American Historical Association (AHA) convened in Boston and Cambridge. According to Du Bois biographer David Levering Lewis, "The Association then numbered fifteen hundred members and was presided over by James Ford Rhodes, successful Ohio businessman and even more successful author of the arbitral, multi-volume History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850. At this 1899 meeting, there were no Jews, no Negroes, no women to speak of, and all the gays were in the closet."

In 1909, W.E.B. Du Bois addressed the AHA. "His would be the first and last appearance of an African American on the program until 1940."[4]

In a review [November 5, 2000, Washington Post] of Part II of Lewis's biography of Du Bois, Michael R. Winston observed that one historical question not often addressed is also fundamental to an understanding of American history. That questions is "how black Americans developed the psychological stamina and collective social capacity to cope with the sophisticated system of racial domination that white Americans had anchored deeply in law and custom."

Winston continued, "Although any reasonable answer is extraordinarily complex, no adequate one can ignore the man (Du Bois)whose genius was for 70 years at the intellectual epicenter of the struggle to destroy white supremacy as public policy and social fact in the United States."

Imperial Japan

Du Bois became impressed by the growing strength of Imperial Japan following the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War. Du Bois saw the victory of Japan over Tsarist Russia as an example of "colored pride". According to historian David Levering Lewis, Du Bois became a willing part of Japan's "Negro Propaganda Operations" run by Japanese academic and Imperial Agent Hikida Yasuichi.

After traveling to the United States to speak with University students at Howard University, Scripps College and Tuskegee University, Yasuichi became closely involved in shaping Du Bois's opinions of Imperial Japan. In 1936 Yasuichi and the Japanese Ambassador arranged a junket for Du Bois and a small group of fellow academics. The trip included stops in Japan, China, and the Soviet Union, although the Soviet leg was canceled because Du Bois' diplomatic contact, Karl Radek, had been swept up in Stalin's purges. While on the Chinese leg of the trip, Du Bois commented that the source of Chinese-Japanese enmity was China's "submission to white aggression and Japan's resistance", and he asked the Chinese people to welcome the Japanese as liberators. The effectiveness of the Japanese propaganda campaign was also seen when Du Bois joined a large group of African American academics that cited the Mukden Incident to justify occupation and annexation of southern Manchuria.

Joined Communist Party at Age 93

Du Bois was investigated by the FBI, who claimed in May of 1942 that "[h]is writing indicates him to be a socialist," and that he "has been called a Communist and at the same time criticized by the Communist Party."

Du Bois visited Communist China during the Great Leap Forward. Also, in the 16 March 1953 issue of The National Guardian, Du Bois wrote "Joseph Stalin was a great man; few other men of the 20th century approach his stature."

Du Bois was chairman of the Peace Information Center at the start of the Korean War. He was among the signers of the Stockholm Peace Pledge, which opposed the use of nuclear weapons. He was indicted in the United States under the Foreign Agents Registration Act and acquitted for lack of evidence. W.E.B. Du Bois became disillusioned with both black capitalism and racism in the United States. In 1959, Du Bois received the Lenin Peace Prize. In 1961, at the age of 93, he joined the Communist Party, USA and announced his membership in The New York Times.

Becomes Citizen of Ghana at Age 95

Du Bois was invited to Ghana in 1961 by President Kwame Nkrumah to direct the Encyclopedia Africana, a government production, and a long-held dream of his. When, in 1963, he was refused a new U.S. passport, he and his wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, became citizens of Ghana. Du Bois' health had declined in 1962, and on August 27, 1963 he died in Accra, Ghana at the age of ninety-five, one day before Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.

In 1992, the United States honored W.E.B. Du Bois with his portrait on a postage stamp. On October 5, 1994, the main library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst was named after him.

Legacy

(Will begin this section soon)

Biographies

- David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868-1919 (Owl Books 1994). Winner of the 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Biography[5]

- David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century 1919-1963 (Owl Books 2001). Covers the second half of the life of W.E.B. Du Bois, charting 44 years of the culture and politics of race in the United States. Winner of the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Biography [6].

- Manning Marable, W.E.B Du Bois: Black Radical Democrat (Paradigm Publishers 2005).

Books, Publications, and Articles by W.E.B Du Bois

Among those listed below, the most important are probably Black Reconstruction (1935); Black Folk Then and Now: An Essay in the History and Sociology of the Negro Race (1939); Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept (1940); and Color and Democracy (1945).

- The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America: 1638–1870 PhD dissertation, 1896, (Harvard Historical Studies, Longmans, Green, and Co.: New York) Full Text

- The Study of the Negro Problems (1898)

- The Philadelphia Negro (1899)

- The Negro in Business (1899)

- The Evolution of Negro Leadership. The Dial, 31 (July 16, 1901).

- The Souls of Black Folk. 1903/1999 ISBN 039397393X

- The Talented Tenth, second chapter of The Negro Problem, a collection of articles by African Americans (September 1903).

- Voice of the Negro II (September 1905)

- John Brown: A Biography (1909)

- Efforts for Social Betterment among Negro Americans (1909)

- Atlanta University's Studies of the Negro Problem (1897-1910)

- The Quest of the Silver Fleece 1911

- The Negro (1915)

- Darkwater (1920)

- The Gift of Black Folk (1924)

- Dark Princess: A Romance (1928)

- Africa, its Geography, People and Products (1930)

- Africa: Its Place in Modern History (1930)

- Black Reconstruction: An Essay toward a History of the Part which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880 (1935)

- What the Negro has Done for the United States and Texas (1936)

- Black Folk, Then and Now (1939)

- Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept (1940)

- Color and Democracy: Colonies and Peace (1945)

- The Encyclopedia of the Negro(1946)

- The World and Africa (1946)

- Peace is Dangerous (1951)

- I take my stand for Peace (1951)

- In Battle for Peace (1952)

- The Black Flame: A Trilogy

- The Ordeal of Mansart (1957)

- Mansart Builds a School (1959)

- Africa in Battle Against Colonialism, Racialism, Imprialism (1960)

- Worlds of Color (1961)

- An ABC of Color: Selections from Over a Half Century of the Writings of W.E.B. Du Bois (1963)

- The World and Africa, An Inquiry into the Part Which Africa has Played in World History (1965)

- The Autobiography of W.E. Burghardt Du Bois (International publishers, 1968)

- The American Negro Academy Occasional Papers, 1897, No. 2 "The Conservation Of Races" full text

awfasdfws

Further reading

- Eric J. Sundquist, ed.; The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader Oxford University Press. 1996

- Broderick Francis L. W. E. B. Du Bois: Negro Leader in a Time of Crisis Stanford University Press, 1959.

- Horne Gerald. Black and Red: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Afro-American Response to the Cold War, 1944-1963 State University of New York Press, 1986

- Meier August. Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington University of Michigan Press, 1963.

- Rampersad Arnold. The Art and Imagination of W. E. B. Du Bois. Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Rudwick Elliott M. W. E. B. Du Bois: Propagandist of the Negro Protest. 1960

References and external links

- W.E.B. Du Bois, The Autobiography of W. E. Burghardt Du Bois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century. New York: International Publishers Co. Inc., 1968, pp. 438-440.

- Online articles by Du Bois

- "A Biographical Sketch of W.E.B. Du Bois" by Gerald C. Hynes

- Review materials for studying W.E.B. Du Bois

- FBI File of William E.B. Du Bois

- The W.E.B. Du Bois Virtual University

- Fighting Fire with Fire: African Americans and Hereditarian Thinking, 1900-1942

- The Talented Tenth

- W.E.B. Du Bois and Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity

- Works by W. E. B. Du Bois. Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.