Difference between revisions of "Santiago Ramón y Cajal" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

'''Santiago Ramón y Cajal''' (May 1, 1852 – October 17, 1934) was a [[Spanish people|Spanish]] [[histology|histologist]] and [[physician]] who (along with [[Camillo Golgi]]) won the [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]] in 1906 for establishing the [[neuron]] (or nerve cell) as the primary structural and functional unit of the [[nervous system]]. Ramón y Cajal’s proposal that neurons were discrete cells that communicated with each other via specialized junctions, or spaces, between cells, became known as the [[neuron doctrine]], now one of the central tenets of modern [[neuroscience]]. | '''Santiago Ramón y Cajal''' (May 1, 1852 – October 17, 1934) was a [[Spanish people|Spanish]] [[histology|histologist]] and [[physician]] who (along with [[Camillo Golgi]]) won the [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]] in 1906 for establishing the [[neuron]] (or nerve cell) as the primary structural and functional unit of the [[nervous system]]. Ramón y Cajal’s proposal that neurons were discrete cells that communicated with each other via specialized junctions, or spaces, between cells, became known as the [[neuron doctrine]], now one of the central tenets of modern [[neuroscience]]. | ||

| − | To observe the structure of individual neurons, Ramón y Cajal used [[Golgi's method|a silver staining method]] developed by Italian | + | To observe the structure of individual neurons, Ramón y Cajal used [[Golgi's method|a silver staining method]] developed by Italian anatomist Camillo Golgi, who supported the prevailing view of the time that the nervous system was a reticulum, or a connected meshwork, rather than a system made up of discrete [[cell (biology)|cells]]. Convinced that the brain needed independent neurons to function, Ramón y Cajal persisted, modifying Golgi's technique until he obtained clear pictures of distinctly bounded nerve endings. |

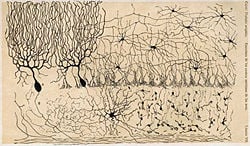

[[Image: CajalCerebellum.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Ramón y Cajal’s beautiful and meticulously rendered drawings of neurons are still used in textbooks today.]] | [[Image: CajalCerebellum.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Ramón y Cajal’s beautiful and meticulously rendered drawings of neurons are still used in textbooks today.]] | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Although he became one of the founders of neuroscience, as a young man Ramón y Cajal wanted to be an artist, and vision would play a central role in his scientific contribution. Ramón y Cajal felt the most essential quality of a scientist was the ability to see clearly: according to Cajal, Golgi was actually seeing separate cells when he looked at the stains, but believed he was seeing a net because he fell prey to suggestion (Otis 2001). | Although he became one of the founders of neuroscience, as a young man Ramón y Cajal wanted to be an artist, and vision would play a central role in his scientific contribution. Ramón y Cajal felt the most essential quality of a scientist was the ability to see clearly: according to Cajal, Golgi was actually seeing separate cells when he looked at the stains, but believed he was seeing a net because he fell prey to suggestion (Otis 2001). | ||

| − | Ramón y Cajal’s artistic leanings extended to the writing of fiction: one year before receiving the Nobel, he published a science-fiction collection called "Vacation Stories" (''Cuentos de vacaciones'') under the pen name "Dr. Bacteria." Tackling issues of ethics in science as well and challenging established views on organized religion and social class, the stories indicate | + | Ramón y Cajal’s artistic leanings extended to the writing of fiction: one year before receiving the Nobel, he published a science-fiction collection called "Vacation Stories" (''Cuentos de vacaciones'') under the pen name "Dr. Bacteria." Tackling issues of ethics in science as well and challenging established views on organized religion and social class, the stories indicate a scientist engaged with the larger social and ethical questions of scientific discovery. |

==Contributions to neuroscience== | ==Contributions to neuroscience== | ||

[[Image:Cajal-mi.jpg|200px|left|thumb|Ramón y Cajal in the lab.]] | [[Image:Cajal-mi.jpg|200px|left|thumb|Ramón y Cajal in the lab.]] | ||

| − | + | Before the neuron doctrine was accepted, it was widely believed that the nervous system was a reticulum, or a connected meshwork, rather than a system made up of discrete [[cell (biology)|cells]] (kandel ref).This theory, the [[reticular theory]], held that neurons' [[soma (biology)|somata]] mainly provided nourishment for the system (DeFelipe, 1998). Even after the [[cell theory]] was postulated in the 1830s, most scientists did not believe the theory applied to the brain or nerves. | |

| − | + | The initial failure to accept the doctrine was due in part to inadequate ability to visualize cells using [[microscopes]], which were not developed enough to provide clear pictures of nerves. With the [[staining (microscopy)|cell staining]] techniques of the day, a slice of neural tissue appeared under a microscope as a complex, tangled web and individual cells were difficult to make out. Since neurons have a large number of [[neural process]]es, an individual cell can be quite long and complex, and it can be difficult to find an individual cell when it is closely associated with many other cells. | |

| − | + | Thus, a major breakthrough for the neuron doctrine occurred in the late 1800s when Ramón y Cajal used a technique developed by [[Camillo Golgi]] to visualize neurons. ''Golgi's method'' is a [[nervous tissue]] [[staining]] technique discovered by [[Italy|Italian]] [[physician]] and [[scientist]] [[Camillo Golgi]] (1843-1926) in [[1873]]. Golgi found that by treating [[brain]] tissue with a [[silver chromate]] solution, a relatively small number of [[neuron]]s in the brain were darkly stained. | |

| − | + | The cells in nervous tissue are densely packed and little information on their structures and interconnections can be obtained if all the cells are stained. Furthermore, its thin filamentary extensions—the [[axon]] and the [[dendrite]]s—are too slender and transparent to be seen with normal staining techniques. The Golgi stain is an extremely useful method for neuroanatomical investigations because, for reasons unknown, it stains a very small percentage of cells in a tissue, so one is able to see the complete microstructure of individual neurons without much overlap from other cells in the densely packed brain.Golgi's method stains a limited number of cells at random in their entirety. The mechanism by which this happens is still largely unknown. | |

| − | + | Based on his stains, Golgi concluded that nervous tissue was a continuous reticulum (or web) of interconnected [[cell (biology)|cell]]s much like those in the [[circulatory system]].Using [[Golgi's method]], Ramón y Cajal reached a very different conclusion. He postulated that the [[nervous system]] is made up of billions of separate [[neuron]]s and that these cells are [[polarization|polarized]]. Rather than forming a continuous web, Cajal suggested that neurons communicate with each other via [[synapse|specialized junctions]] called "synapses", a term that was coined by [[Charles Scott Sherrington|Sherrington]] in [[1897]]. This [[hypothesis]] became the basis of the [[neuron doctrine]], which states that the individual unit of the nervous system is a single neuron. [[Electron microscope|Electron microscopy]] later showed that a [[cell membrane|plasma membrane]] completely enclosed each neuron, supporting Cajal's [[theory]], and weakening Golgi's reticular theory. | |

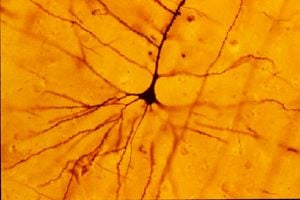

| − | + | [[Image:GolgiStainedPyramidalCell.jpg|thumb|A human neocortical [[pyramidal neuron]] stained via [[Golgi's method|Golgi technique]].]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | For their technique and discovery respectively, Golgi and Ramón y Cajal shared the 1906 [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]]. Golgi could not tell for certain that neurons were not connected, and in his acceptance speech he defended the reticular theory. Ramón y Cajal, in ''his'' speech, contradicted that of Golgi and defended the now accepted neuron doctrine. A paper written in 1891 by [[Wilhelm von Waldeyer]], a supporter of Ramón y Cajal who coined the term ''neuron'', debunked the reticular theory and outlined the Neuron Doctrine. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | For their technique and discovery respectively, Golgi and Ramón y Cajal shared the 1906 [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]]. Golgi could not tell for certain that neurons were not connected, and in his acceptance speech he defended the reticular theory. Ramón y Cajal, in ''his'' speech, contradicted that of Golgi and defended the now accepted neuron doctrine. | ||

| − | |||

| − | A paper written in 1891 by [[Wilhelm von Waldeyer]], a supporter of Ramón y Cajal, debunked the reticular theory and outlined the Neuron Doctrine. | ||

Ramón y Cajal also proposed that the way [[axon]]s grow is via a [[growth cone]] at their ends. He understood that neural cells could sense chemical signals that indicated a direction for growth, a process called [[chemotaxis]]. | Ramón y Cajal also proposed that the way [[axon]]s grow is via a [[growth cone]] at their ends. He understood that neural cells could sense chemical signals that indicated a direction for growth, a process called [[chemotaxis]]. | ||

| Line 68: | Line 41: | ||

Image:PurkinjeCell.jpg|Drawing of [[Purkinje cell]]s (A) and granule cells (B) from pigeon cerebellum by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 1899. Instituto Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain. | Image:PurkinjeCell.jpg|Drawing of [[Purkinje cell]]s (A) and granule cells (B) from pigeon cerebellum by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 1899. Instituto Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain. | ||

Image:Cajal-Retzius cell drawing by Cajal 1891.gif|Drawing of [[Cajal-Retzius cell]]s, 1891. | Image:Cajal-Retzius cell drawing by Cajal 1891.gif|Drawing of [[Cajal-Retzius cell]]s, 1891. | ||

| − | |||

Image:Purkinje cell by Cajal.png|Drawing of a [[Purkinje cell]] in the [[cerebellum]] [[Cerebellar cortex|cortex]] done by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, clearly demonstrating the power of Golgi's staining method to reveal fine detail. | Image:Purkinje cell by Cajal.png|Drawing of a [[Purkinje cell]] in the [[cerebellum]] [[Cerebellar cortex|cortex]] done by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, clearly demonstrating the power of Golgi's staining method to reveal fine detail. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==Ramón y Cajal as writer: ''Vacation Stories''== | ==Ramón y Cajal as writer: ''Vacation Stories''== | ||

| − | In 1905, he published five science-fictional "Vacation Stories" under the pen name | + | In 1905, he published five science-fictional "Vacation Stories" under the pen name Dr. Bacteria. |

| − | + | Though written in 1885-86, the period immediately preceding his scientific breakthrough, the stories were edited extensively in 1905, so that they could be associated w/ a Spanish literary movement called the Generation of 1898. A group of [[novel]]ists, [[poet]]s, [[essay]]ists, and [[philosopher]]s that included [[Azorín]], [[Pío Baroja]], and [[Miguel de Unamuno]], the Generation of 1898 focused on the individual will as a mean’s to regenerate Spain, perceived of as on a slow cultural decline since the mid-17th century, and called for political and educational reform. | |

| − | The | + | == Biography == |

| + | The son of Justo Ramón and Antonia Cajal, Ramón y Cajal was born of Aragonese parents in [[Petilla de Aragón]], a poor, rural enclave in [[Aragon]], in northeastern [[Spain]]. As a child he was transferred between many different schools due to his unruly behaviour and [[Authoritarianism|anti-authoritarian]] attitude. An extreme example of his precociousness and rebelliousness is his imprisonment at the age of eleven for destroying the town gate with a homemade [[cannon]]. He was an avid painter, artist, and [[gymnast]], who preferred being out of doors rather than trapped in school memorizing lessons. | ||

| − | + | However, Justo Ramón, who himself had escaped poverty by becoming first a surgeon and later a physician, was determined to make his son a physician. Ramón y Cajal attended the medical school of [[Zaragoza]], from which he graduated in 1873. A mandatory draft made him a military doctor, with the rank of caption, in the Spanish Army; he was sent him to first the Carlist campaign and later to Cuba (where uprising of Cuban nationalists demanding independence from Spain) served as a medical [[officer (armed forces)|officer]] in the [[Spanish Army]], where he contracted [[malaria]]. After returning to Spain, he married Silveria Fañanás García, with whom he had seven children (two of whom died in childhood). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Ramón y Cajal | + | Ramón y Cajal secured a post as an assistant professor at Zaragoza teaching anatomy in 1879, and was appointed as a [[university]] [[professor]] at [[Universitat de València|Valencia]] in 1881. In 1883, he was made chair of the anatomy department there. He later held professorships in both [[Barcelona]] and Madrid, remaining in the latter position for 30 years. He was Director of the Zaragoza Museum (1879), Director of the National Institute of Hygiene (1899), and founder of the {{lang|es|''Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas''}} (1922) (later renamed to the {{lang|es|''Instituto Cajal''}}, or [[Cajal Institute]]). Ramón y Cajal died in Madrid in 1934. |

== Selected works == | == Selected works == | ||

| − | Ramón y Cajal published over 200 scientific texts and articles, many of which were translated into [[French]] and [[German language|German]], though — //. Among his most notable publications | + | Ramón y Cajal published over 200 scientific texts and articles, many of which were translated into [[French]] and [[German language|German]], though — lamented the isolation of sp scientists //. Among his most notable publications are works of memoir and fiction. |

*1894-1904: ''Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates'' 2 vols. (''Textura del Sistema Nervioso del Hombre y los Vertebrados'') | *1894-1904: ''Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates'' 2 vols. (''Textura del Sistema Nervioso del Hombre y los Vertebrados'') | ||

| Line 109: | Line 73: | ||

*Ramón y Cajal, S. 1999 (1897). ''Advice for a Young Investigator''. Trans. N. Swanson and L.W. Swanson. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0262681501 | *Ramón y Cajal, S. 1999 (1897). ''Advice for a Young Investigator''. Trans. N. Swanson and L.W. Swanson. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0262681501 | ||

*Ramón y Cajal, S. 2001 (1905). ''Vacation Stories: Five Science Fiction Tales''. Trans. L. Otis. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. | *Ramón y Cajal, S. 2001 (1905). ''Vacation Stories: Five Science Fiction Tales''. Trans. L. Otis. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. | ||

| + | *[[Eric Richard Kandel|Kandel E.R.]], Schwartz, J.H., Jessell, T.M. 2000. ''[[Principles of Neural Science]]'', 4th ed., Page 23. McGraw-Hill, New York. | ||

| + | DeFelipe J. 1998. [http://www.psu.edu/nasa/cajal.htm Cajal]. ''MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences'', MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 17:56, 20 June 2007

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (May 1, 1852 – October 17, 1934) was a Spanish histologist and physician who (along with Camillo Golgi) won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906 for establishing the neuron (or nerve cell) as the primary structural and functional unit of the nervous system. Ramón y Cajal’s proposal that neurons were discrete cells that communicated with each other via specialized junctions, or spaces, between cells, became known as the neuron doctrine, now one of the central tenets of modern neuroscience.

To observe the structure of individual neurons, Ramón y Cajal used a silver staining method developed by Italian anatomist Camillo Golgi, who supported the prevailing view of the time that the nervous system was a reticulum, or a connected meshwork, rather than a system made up of discrete cells. Convinced that the brain needed independent neurons to function, Ramón y Cajal persisted, modifying Golgi's technique until he obtained clear pictures of distinctly bounded nerve endings.

Although he became one of the founders of neuroscience, as a young man Ramón y Cajal wanted to be an artist, and vision would play a central role in his scientific contribution. Ramón y Cajal felt the most essential quality of a scientist was the ability to see clearly: according to Cajal, Golgi was actually seeing separate cells when he looked at the stains, but believed he was seeing a net because he fell prey to suggestion (Otis 2001).

Ramón y Cajal’s artistic leanings extended to the writing of fiction: one year before receiving the Nobel, he published a science-fiction collection called "Vacation Stories" (Cuentos de vacaciones) under the pen name "Dr. Bacteria." Tackling issues of ethics in science as well and challenging established views on organized religion and social class, the stories indicate a scientist engaged with the larger social and ethical questions of scientific discovery.

Contributions to neuroscience

Before the neuron doctrine was accepted, it was widely believed that the nervous system was a reticulum, or a connected meshwork, rather than a system made up of discrete cells (kandel ref).This theory, the reticular theory, held that neurons' somata mainly provided nourishment for the system (DeFelipe, 1998). Even after the cell theory was postulated in the 1830s, most scientists did not believe the theory applied to the brain or nerves.

The initial failure to accept the doctrine was due in part to inadequate ability to visualize cells using microscopes, which were not developed enough to provide clear pictures of nerves. With the cell staining techniques of the day, a slice of neural tissue appeared under a microscope as a complex, tangled web and individual cells were difficult to make out. Since neurons have a large number of neural processes, an individual cell can be quite long and complex, and it can be difficult to find an individual cell when it is closely associated with many other cells.

Thus, a major breakthrough for the neuron doctrine occurred in the late 1800s when Ramón y Cajal used a technique developed by Camillo Golgi to visualize neurons. Golgi's method is a nervous tissue staining technique discovered by Italian physician and scientist Camillo Golgi (1843-1926) in 1873. Golgi found that by treating brain tissue with a silver chromate solution, a relatively small number of neurons in the brain were darkly stained.

The cells in nervous tissue are densely packed and little information on their structures and interconnections can be obtained if all the cells are stained. Furthermore, its thin filamentary extensions—the axon and the dendrites—are too slender and transparent to be seen with normal staining techniques. The Golgi stain is an extremely useful method for neuroanatomical investigations because, for reasons unknown, it stains a very small percentage of cells in a tissue, so one is able to see the complete microstructure of individual neurons without much overlap from other cells in the densely packed brain.Golgi's method stains a limited number of cells at random in their entirety. The mechanism by which this happens is still largely unknown.

Based on his stains, Golgi concluded that nervous tissue was a continuous reticulum (or web) of interconnected cells much like those in the circulatory system.Using Golgi's method, Ramón y Cajal reached a very different conclusion. He postulated that the nervous system is made up of billions of separate neurons and that these cells are polarized. Rather than forming a continuous web, Cajal suggested that neurons communicate with each other via specialized junctions called "synapses", a term that was coined by Sherrington in 1897. This hypothesis became the basis of the neuron doctrine, which states that the individual unit of the nervous system is a single neuron. Electron microscopy later showed that a plasma membrane completely enclosed each neuron, supporting Cajal's theory, and weakening Golgi's reticular theory.

For their technique and discovery respectively, Golgi and Ramón y Cajal shared the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Golgi could not tell for certain that neurons were not connected, and in his acceptance speech he defended the reticular theory. Ramón y Cajal, in his speech, contradicted that of Golgi and defended the now accepted neuron doctrine. A paper written in 1891 by Wilhelm von Waldeyer, a supporter of Ramón y Cajal who coined the term neuron, debunked the reticular theory and outlined the Neuron Doctrine.

Ramón y Cajal also proposed that the way axons grow is via a growth cone at their ends. He understood that neural cells could sense chemical signals that indicated a direction for growth, a process called chemotaxis.

The relation between art and science in Ramón y Cajal's career

text

Ramón y Cajal as writer: Vacation Stories

In 1905, he published five science-fictional "Vacation Stories" under the pen name Dr. Bacteria.

Though written in 1885-86, the period immediately preceding his scientific breakthrough, the stories were edited extensively in 1905, so that they could be associated w/ a Spanish literary movement called the Generation of 1898. A group of novelists, poets, essayists, and philosophers that included Azorín, Pío Baroja, and Miguel de Unamuno, the Generation of 1898 focused on the individual will as a mean’s to regenerate Spain, perceived of as on a slow cultural decline since the mid-17th century, and called for political and educational reform.

Biography

The son of Justo Ramón and Antonia Cajal, Ramón y Cajal was born of Aragonese parents in Petilla de Aragón, a poor, rural enclave in Aragon, in northeastern Spain. As a child he was transferred between many different schools due to his unruly behaviour and anti-authoritarian attitude. An extreme example of his precociousness and rebelliousness is his imprisonment at the age of eleven for destroying the town gate with a homemade cannon. He was an avid painter, artist, and gymnast, who preferred being out of doors rather than trapped in school memorizing lessons.

However, Justo Ramón, who himself had escaped poverty by becoming first a surgeon and later a physician, was determined to make his son a physician. Ramón y Cajal attended the medical school of Zaragoza, from which he graduated in 1873. A mandatory draft made him a military doctor, with the rank of caption, in the Spanish Army; he was sent him to first the Carlist campaign and later to Cuba (where uprising of Cuban nationalists demanding independence from Spain) served as a medical officer in the Spanish Army, where he contracted malaria. After returning to Spain, he married Silveria Fañanás García, with whom he had seven children (two of whom died in childhood).

Ramón y Cajal secured a post as an assistant professor at Zaragoza teaching anatomy in 1879, and was appointed as a university professor at Valencia in 1881. In 1883, he was made chair of the anatomy department there. He later held professorships in both Barcelona and Madrid, remaining in the latter position for 30 years. He was Director of the Zaragoza Museum (1879), Director of the National Institute of Hygiene (1899), and founder of the Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas (1922) (later renamed to the Instituto Cajal, or Cajal Institute). Ramón y Cajal died in Madrid in 1934.

Selected works

Ramón y Cajal published over 200 scientific texts and articles, many of which were translated into French and German, though — lamented the isolation of sp scientists //. Among his most notable publications are works of memoir and fiction.

- 1894-1904: Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates 2 vols. (Textura del Sistema Nervioso del Hombre y los Vertebrados)

- 1897: Advice for a Young Investigator (Reglas y consejos sobre le investigación cientifica)

- 1905: Vacation Stories (Cuentos de vacaciones)

- 1913-1914: Degeneration and regeneration of the nervous system 2 vols. (Estudios sobre la degeneración y regeneración del sistema nervioso)

- 1917: Recollections of My Life (Recuerdos de mi vida)

- 1918: Manual of general pathological anatomy (Manual técnico de anatomía patológica)

- 1921: Cafe Conversations (Charlas de Café)

- 1934: The World From an Eighty-Year-Old's Point of View (El mundo visto a los ochenta años)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Everdell, W.R. 1998. The First Moderns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226224805

- Ramón y Cajal, S. 1937. Recuerdos de mi Vida. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 8420622907

- Ramón y Cajal, S. 1999 (1897). Advice for a Young Investigator. Trans. N. Swanson and L.W. Swanson. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0262681501

- Ramón y Cajal, S. 2001 (1905). Vacation Stories: Five Science Fiction Tales. Trans. L. Otis. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Kandel E.R., Schwartz, J.H., Jessell, T.M. 2000. Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed., Page 23. McGraw-Hill, New York.

DeFelipe J. 1998. Cajal. MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

External links

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906

- Life and discoveries of Cajal

- Ramon y Cajal, an Aragonese Nobel Prize

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.