Ruhollah Khomeini

Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Ruhollah Mosavi Khomeini (listen (Persian pronunciation) ▶) sometimes referred to by the name Seyyed Ruhollah Mosavi Hendizadeh (Persian: روح الله موسوی خمینی Rūḥollāh Mūsavī Khomeynī (May 17, 1900)[1] – June 3, 1989) was a Shi`i Muslim cleric and marja (religious authority), and the political leader of the 1979 Iranian Revolution which saw the overthrow of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran. Following the revolution, Khomeini became Supreme Leader of Iran—the paramount symbolic political figure of the new Islamic Republic until his death.

He was considered a high spiritual leader (marja al-taqlid, "source of imitation") to many Shi'a Muslims. Khomeini was also a highly-influential and innovative Islamic political theorist, most noted for his development of the theory of velayat-e faqih, the "guardianship of the jurisconsult (clerical authority)." He was named TIME's Man of the Year in 1979 and also one of TIME magazine's 100 most influential people of the twentieth century. He is credited by many with encouraging anti-Western sentiment in the Muslim world, famously calling the United States the "great Satan." In 1980, the seizure of hostages in the US Embassy (now called the "den of spies" by Iranians) raised tension throughout the region. Iran has subsequently tried to export its Islamic revolution, most notably to Iraq but also to Bosnia and among the Palestinians as well as in Lebanon, where it support the anti-Israeli political and para-military organization known as Hizbullah. Many Sunni Muslims also regard the Islamic Republic of Iran, which owes its constitution to Khomeini, as a model that could be emulated elsewhere in order to replace existing givenments which, based on Western models, are deemed to be non-Islamic.

Early Life

Khomeini was born in the town of Khomein, about 100 miles from the city of Qom, the center of theological education in Iran. In the early 1930, he adopted the name of his town of birth as his family name. His family were descended from the prophet Muhammad and from the seventh Shi'a Imam, Musa. For generations, they had been religious scholars and jurists. Khomeini's father died when he was an infant and it was his mother and older brother who raised him. He attended theological academies at Najaf and Samarra before moving to study at Qum in 1923. Shi'a scholars rise up through the ranks of jurist by attracting more followers, people who pledge to obey their rulings and to heed their advice. Khomeini gradually moved up the hierarchy, which begins with khatib, then moves through mujtahid, hujjat-al-islam, hujjat-al-islam wa al-Muslimeen to that of Ayotollah. At the time, the senior scholars did not intervene much in political matters. By the start of the 1950s, he had earned the title of Ayotollah, or "sign of God," which identified him as one of the more senior scholars. This means that his followers, collectively muqalid, had reached a critical mass. In 1955, a national anti-Bahai'i campaign gained momentum and Khomeini tried to interest Ayotollah Boroujerdi, the senior scholar, in leading this but the Ayotollah was not inclined to offer his leadership. Khomeini continued to attract students, many of whom would assist him in eventually toppling the Shah and initiating his Islamic revolution. Ayotollah Boroujerdi died March 31, 1961. Khomeini, already a Grand Ayotollah, was now sufficiently senior to be a contender for the title of Maja-e-Taqlid (point of reference or source of emulation). He was also now in a position to venture into the political arena, having long opposes the pro-Western and, in his view, anti-Islamic policies of the Shah.

Opposition to the White Revolution

In January 1963, the Shah announced the "White Revolution," a six-point program of reform calling for land reform, nationalization of the forests, the sale of state-owned enterprises to private interests, electoral changes to enfranchise women, profit sharing in industry, and a literacy campaign in the nation's schools. All of these initiatives were regarded as dangerous, Westernizing trends by traditionalists, especially by the powerful and privileged Shiite ulama (religious scholars) who felt highly threatened.

Ayatollah Khomeini summoned a meeting of his colleagues (other Ayatollahs) in Qom and persuaded the other senior marjas of Qom to decree a boycott of the referendum on the White Revolution. On January 22, 1963 Khomeini issued a strongly worded declaration denouncing the Shah and his plans. Two days later Shah took armored column to Qom, and he delivered a speech harshly attacking the ulama as a class.

Khomeini continued his denunciation of the Shah's programs, issuing a manifesto that also bore the signatures of eight other senior religious scholars. In it he listed the various ways in which the Shah allegedly had violated the constitution, condemned the spread of moral corruption in the country, and accused the Shah of submission to America and Israel. He also decreed that the Norooz celebrations for the Iranian year 1342 (which fell on March 21, 1963) be canceled as a sign of protest against government policies.

On the afternoon of 'Ashoura (June 3, 1963), Khomeini delivered a speech at the Feyziyeh madrassah drawing parallels between the infamous tyrant Yazid and the Shah, denouncing Reza Pahlavi as a "wretched miserable man," and warning him that if he did not change his ways the day would come when the people would offer up thanks for his departure from the country.[2]

On June 5, 1963, (15 of Khordad), two days after this public denunciation of the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi Khomeini was arrested, sparking three days of major riots throughout Iran that led to the deaths of some 400, which is called Movement of 15 Khordad.[3] Khomeini was kept under house arrest for eight months and he was released in 1964.

Opposition against capitulation

During November 1964, he made a denunciation of both the Shah and the United States, this time in response to the "capitulations" or diplomatic immunity granted to American military personnel in Iran by the Shah[4] and consider him a puppet of the West;[5] In November 1964 Khomeini was re-arrested and sent into exile.

Life in exile

Khomeini spent over 14 years in exile, mostly in the holy Shia city of Najaf, Iraq. Initially he was sent to Turkey on November 4, 1964 where he stayed in the city of Bursa for less than a year. He was hosted by a Turkish Colonel named Ali Cetiner in his own residence. Later in October 1965 he was allowed to move to Najaf, Iraq, where he stayed until being forced to leave in 1978, after then-Vice President Saddam Hussein forced him out (the two countries would fight a bitter eight year war 1980-1988 only a year after the two reached power in 1979) after which he went to Neauphle-le-Château in France on a tourist visa, apparently not seeking political asylum, where he stayed for four months. According to Alexandre de Marenches, chief of External Documentation and Counter-Espionage Service (now known as the DGSE), France would have suggested to the shah to "organize a fatal accident for Khomeini"; the shah declined the assassination offer, observing that would have made Khomeini a martyr.

Logically, in the 1970s, as contrasted with the 1940s, he no longer accepted the idea of a limited monarchy under the Iranian Constitution of 1906-1907, an idea that was clearly evidenced by his book Kashf-e Assrar. In his Islamic Government (Hokumat-e Islami)—which is a collection of his lectures in Najaf (Iraq) published in 1970—he rejected both the Iranian Constitution as an alien import from Belgium and monarchy in general. He believed that the government was an un-Islamic and illegitimate institution usurping the legitimate authority of the supreme religious leader (Faqih), who should rule as both the spiritual and temporal guardian of the Muslim community (Umma).[6]

In early 1970 Khomeini gave a series of lectures in Najaf on Islamic Government, later published as a book titled variously Islamic Government or Islamic Government, Authority of the Jurist (Hokumat-e Islami: Velayat-e faqih). This was his most famous and influential work and laid out his ideas on governance (at that time):

- That the laws of society should be made up only of the laws of God (Sharia), which cover "all human affairs" and "provide instruction and establish norms" for every "topic" in "human life."[7]

- Since Sharia, or Islamic law, is the proper law, those holding government posts should have knowledge of Sharia (Islamic jurists are such people), and that the country's ruler should be a faqih who "surpasses all others in knowledge" of Islamic law and justice,[8] (known as a marja`), as well as having intelligence and administrative ability. Rule by monarchs and/or assemblies of "those claiming to be representatives of the majority of the people" (i.e., elected parliaments and legislatures) have been proclaimed "wrong" by Islam.[9]

- This system of clerical rule is necessary to prevent injustice: corruption, oppression by the powerful over the poor and weak, innovation and deviation of Islam and Sharia law; and also to destroy anti-Islamic influence and conspiracies by non-Muslim foreign powers.[10]

A modified form of this wilayat al-faqih system was adopted after Khomeini and his followers took power, and Khomeini was the Islamic Republic's first "Guardian" or Supreme Leader.

In the meantime, however, Khomeini took care not to publicize his ideas for clerical rule outside of his Islamic network of opposition to the Shah which he worked to build and strengthen over the next decade. Cassette copies of his lectures fiercely denouncing the Shah as (for example) "… the Jewish agent, the American snake whose head must be smashed with a stone," [11] became common items in the markets of Iran,[12] helped to demythologize the power and dignity of the Shah and his reign. Aware of the importance of broadening his base, Khomeini reached out to Islamic reformist and secular enemies of the Shah, despite his long-term ideological incompatibility with them.

After the death of Dr. Ali Shariati, in 1977, an Islamic reformist and political revolutionary author/academic/philosopher who greatly popularized the Islamic revival among young educated Iranians, Khomeini became the most influential leader of the opposition to the Shah perceived by many Iranians as the spiritual, if not political, leader of revolt. As protest grew so did his profile and importance. Although thousands of kilometers away from Iran in Paris, Khomeini set the course of the revolution, urging Iranians not to compromise and ordering work stoppages against the regime. During the last few months of his exile, Khomeini received a constant stream of reporters, supporters, and notables, eager to hear the spiritual leader of the revolution.[13]

Supreme leader of Islamic Republic of Iran

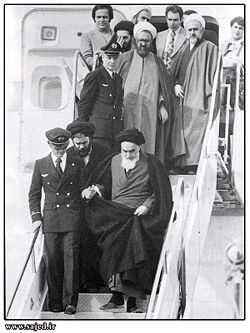

Return to Iran

Khomeini had refused to return to Iran until the Shah left. On January 16, 1979, the Shah did leave the country (ostensibly "on vacation"), never to return. Two weeks later on Thursday, February 1, 1979, Imam Khomeini returned in triumph to Iran, welcomed by a joyous crowd estimated at least three million.[14]

On the airplane on his way to Iran Khomeini was asked by reporter Peter Jennings: "What do you feel in returning to Iran?" Khomeini answered "Hic ehsâsi nadâram" (I don't feel a thing). This statement is often referred to by those who oppose Khomeini as demonstrating the ruthlessness and heartlessness of Khomeini. His supporters, however, attribute this comment as demonstrating the mystic aspiration and selflessness of Khomeini's revolution.

Khomeini adamantly opposed the provisional government of Shapour Bakhtiar, promising: "I shall kick their teeth in. I appoint the government. I appoint the government by support of this nation."[15] On February 11, Khomeini appointed his own competing interim prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan, demanding: "since I have appointed him, he must be obeyed." It was 'God's government' he warned, "disobedience against which was a `revolt against God."[16]

Establishment of new government

As Khomeini's movement gained momentum, soldiers began to defect to his side and Khomeini declared jihad on soldiers who did not surrender.[17] On February 11, as revolt spread and armories were taken over, the military declared neutrality and the Bakhtiar regime collapsed.[18] On March 30, 1979, and March 31, 1979, a referendum to replace the monarchy with an Islamic Republic passed with 98 percent voting "yes".[19]

Islamic constitution and its opposition

As Ayatollah Khomeini had mentioned during his exile and people support this idea through mass demonstrations Islamic constitution was written. However communists as well as liberals protest against it but they were minority and couldn't change the situation. Although revolutionaries were now in charge and Khomeini was their leader, many of them, both secular and religious, did not approve and/or know of Khomeini's plan for Islamic government by wilayat al-faqih, or rule by a marja` Islamic cleric - that is, by him. Nor did the new provisional constitution for the Islamic Republic, which revolutionaries had been working on with Khomeini's approval, include a post of supreme jurist ruler. In the coming months, Khomeini and his supporters worked to suppress these former allies turned opponents, and rewrite the proposed constitution. Newspapers were closing and those protesting the closings attacked[20] and opposition groups such as the National Democratic Front and Muslim People's Republican Party were attacked and finally banned[21]. Through questionable balloting pro-Khomeini candidates dominated the Assembly of Experts[22] and revised the proposed constitution to include a clerical Supreme Leader, and a Council of Guardians to veto unIslamic legislation and screen candidates for office.

In November 1979 the new constitution of the Islamic Republic was passed by referendum. Khomeini himself became instituted as the Supreme Leader , and officially decreed as the "Leader of the Revolution." On February 4, 1980, Abolhassan Banisadr was elected as the first president of Iran. Helping pass the controversial constitution was the Iran hostage crisis.

Hostage crisis

On October 22, 1979, the Shah was admitted into the United States for medical treatment for lymphoma. There was an immediate outcry in Iran and on November 4, 1979, a group of students, all of whom were ardent followers of Khomeini, seized the United States embassy in Tehran, taking 63 American citizens as hostage. After a judicious delay, Khomeini supported the hostage-takers under the slogan "America can't do a damn thing." Fifty of the hostages were held prisoner for 444 days — an event usually referred to as the Iran hostage crisis. The hostage-takers justified this violation of long-established international law as a reaction to American refusal to hand over the Shah for trial and execution. On February 23, 1980, Khomeini proclaimed Iran's Majlis (Assembly) would decide the fate of the American embassy hostages, and demanded that the United States hand over the Shah for trial in Iran for crimes against the nation. Although the Shah died less than a year later, this did not end the crisis. Supporters of Khomeini named the embassy a "Den of Espionage," and publicized the weapons, electronic listening devices, other equipment and many volumes of official and secret classified documents they found there. Others explain the length of the imprisonment on what Khomeini is reported to have told his president: "This action has many benefits. … This has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people's vote without difficulty, and carry out presidential and parliamentary elections."[23] The new theocratic constitution did successfully pass its referendum one month after the hostage-taking, which did succeed in splitting its opposition—radicals supporting the hostage-taking and moderates opposing it.

Relationship with other Islamic and non-aligned countries

Khomeini believed in Muslim unity and solidarity and its spread throughout the world. "Establishing the Islamic state world-wide belong to the great goals of the revolution." [24] He declared the birth week of Muhammad (the week between 12–17 of Rabi' al-awwal) as the "Unity week." Then he declared the last Friday of Ramadan as International Day of Quds in 1979.

Despite his devotion to Islam, Khomeini also emphasized international revolutionary solidarity, expressing support for the PLO, the IRA, Cuba, and the South African anti-apartheid struggle. Terms like "democracy" and "liberalism" considered positive in the West became words of criticism, while "revolution" and "revolutionary" were terms of praise[25].

Iran-Iraq War

Shortly after assuming power, Khomeini began calling for Islamic revolutions across the Muslim world, including Iran's Arab neighbor Iraq,[26] the one large state besides Iran with a Shia majority population. At the same time Saddam Hussein, Iraq's secular Arab nationalist Ba'athist leader, was eager to take advantage of Iran's weakened military and (what he assumed was) revolutionary chaos, and in particular to occupy Iran's adjacent oil-rich province of Khuzestan, and, of course, to undermine Iranian Islamic revolutionary attempts to incite the Shi'a majority of his country.

With what many Iranians believe was the encouragement of the United States, Saudi Arabia and other countries, Iraq soon launched a full scale invasion of Iran, starting what would become the eight-year-long Iran-Iraq War (September 1980–August 1988). A combination of fierce resistance by Iranians and military incompetence by Iraqi forces soon stalled the Iraqi advance and by early 1982 Iran regained almost all the territory lost to the invasion. The invasion rallied Iranians behind the new regime, enhancing Khomeini's stature and allowed him to consolidate and stabilize his leadership. After this reversal, Khomeini refused an Iraqi offer of a truce, instead demanding reparation and toppling of Saddam Hussein from power.[27][28][29]

Although outside powers supplied arms to both sides during the war, the West (America in particular) wanted to be sure the Islamic revolution did not spread to other parts of the oil-exporting Persian Gulf and began to supply Iraq with whatever help it needed. Most rulers of other Muslim countries also supported Iraq out of opposition to the Islamic ideology of Islamic Republic of Iran, which threatened their own native monarchies. On the other hand most Islamic parties and organizations supported Islamic unity with Iran, especially the Shiite ones.[30]

The war continued for another six years, with 450,000 to 950,000 casualties on the Iranian side and at a cost estimated by Iranian officials to total USD $300 billion.[31]

As the costs of the eight-year war mounted, Khomeini, in his words, “drank the cup of poison” and accepted a truce mediated by the United Nations. He strongly denied, however, that pursuit of overthrow of Saddam had been a mistake. In a `Letter to Clergy` he wrote: "… we do not repent, nor are we sorry for even a single moment for our performance during the war. Have we forgotten that we fought to fulfill our religious duty and that the result is a marginal issue?"[32]

As the war ended, the struggles among the clergy resumed and Khomeini’s health began to decline.

Rushdie fatwa

In early 1989, Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for the killing of Salman Rushdie, an India-born British author[33]. Khomeini claimed that Rushdie's murder was a religious duty for Muslims because of his alleged blasphemy against Muhammad in his novel, The Satanic Verses. Rushdie's book contains passages that many Muslims—including Ayatollah Khomeini—considered offensive to Islam and the prophet, but the fatwa has also been attacked for violating the rules of fiqh by not allowing the accused an opportunity to defend himself, and because "even the most rigorous and extreme of the classical jurist only require a Muslims to kill anyone who insults the Prophet in his hearing and in his presence."[34]

Though Rushdie publicly apologized, the fatwa was not revoked. Khomeini explained,

Even if Salman Rushdie repents and becomes the most pious man of all time, it is incumbent on every Muslim to employ everything he has got, his life and wealth, to send him to Hell. [35]

Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator of the book The Satanic Verses, was murdered. Two other translators of the book survived attempted assassinations.

More of Khomeini's fataawa were compiled in The Little Green Book, Sayings of Ayatollah Khomeini, Political, Philosophical, Social and Religious.

Daniel Pipes comments that although Khomeini's fatwa caused Rushdie no physical harm, it accomplished "something far more profound: he stirred something in the soul of many Muslims, reviving a sense of confidence about Islam and an impatience to abide criticism of their faith …. His edict… had the effect of inspiring Islamists around the world to go on the offensive against anyone they perceived as defaming their Prophet, their faith, or even themselves."[36]

As a consequence, Pipes and others declaim a political correctness among non-Muslim scholar of Islam who refrain from criticizing Islam. The increase in death threats, too, against more liberal Muslims increased after Khomeini's edict.

Life under Khomeini

In a speech given to a huge crowd after returning to Iran from exile February 1, 1979, Khomeini made a variety of promises to Iranians for his coming Islamic regime: A popularly elected government that would represent the people of Iran and with which the clergy would not interfere. He promised that “no one should remain homeless in this country,” and that Iranians would have free telephone, heating, electricity, bus services and free oil at their doorstep. While many changes came to Iran under Khomeini, these promises have yet to be fulfilled in the Islamic Republic. [37][38][39][40][41]

More important to Khomeini than the material prosperity of Iranians was their religious devotion:

We, in addition to wanting to improve your material lives, want to improve your spiritual lives … they have deprived us of our spirituality. Don’t be content that we will build real estate, make water and power free, and make buses free. Don’t be content with this. Your spirituality, state of mind, we will ameliorate. We shall elevate you to the rank of humanity. They have led you astray. They have the world so much for you that you ideate these as everything. We shall revitalize both this world and the afterlife. [42]

Under Khomeini's rule, Sharia (Islamic law) was introduced, with the Islamic dress code enforced for both men and women by Islamic Revolutionary Guards and other Islamic groups[43] Women were forced to cover their hair, and men were not allowed to wear shorts. The Iranian educational curriculum was Islamized at all levels with the Islamic Cultural Revolution; the "Committee for Islamization of Universities"[44] carried this out thoroughly.

Opposition to the religious rule of the clergy or Islam in general was often met with harsh punishments. In a talk at the Fayzieah School in Qom, August 30, 1979, Khomeini said "Those who are trying to bring corruption and destruction to our country in the name of democracy will be oppressed. They are worse than Bani-Ghorizeh Jews, and they must be hanged. We will oppress them by God's order and God's call to prayer." [45]

In January of 1979, the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left Iran with his family, but hundreds of former members of the overthrown monarchy and military met their end in firing squads, with critics complaining of "secrecy, vagueness of the charges, the absence of defense lawyers or juries," or the opportunity of the accused "to defend themselves."[46] In later years these were followed in larger numbers by the erstwhile revolutionary allies of Khomeini's movement—Marxists and socialists, mostly university students, who opposed the theocratic regime.[47]

In the 1988 massacre of Iranian prisoners, following the People's Mujahedin of Iran operation Forough-e Javidan against the Islamic Republic, Khomeini issued an order to judicial officials to judge every Iranian political prisoner and kill those who would not repent anti-regime activities. Many say that thousands were swiftly put to death inside the prisons.[48] The suppressed memoirs of Grand Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri reportedly detail the execution of 30,000 political activists.[49]

Although many hoped the revolution would bring freedom of speech and press, this was not to be. In defending forced closing of opposition newspapers and attacks on opposition protesters by club-wielding vigilantes Khomeini explained, `The club of the pen and the club of the tongue is the worst of clubs, whose corruption is a 100 times greater than other clubs.`[50]

Life for religious minorities has been mixed under Khomeini and his successors. Shortly after his return from exile in 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering that Jews and other minorities (except Baha'is) be treated well.[51]

As Haroun Yashyaei, a film producer and former chairman of the Central Jewish Community in Iran has quoted[52]:

"Khomeini didn't mix up our community with Israel and Zionism - he saw us as Iranians,"

Islamic republic government has made a clear effort to distinguish between Zionism as a secular political party that enjoys Jewish symbols and ideals and Judaism as the religion of Moses. By law, several seats in the parliament are reserved for minority religions. Khomeini also called for unity between Sunni and Shi'a Muslims (Sunni Muslims are the largest religious minority in Iran).[53]

Non-Muslim religious minorities, however, do not have equal rights in Khomeini's Islamic Republic. Senior government posts are reserved for Muslims. Jewish and Christian schools must be run by Muslim principals.[54] Compensation for death paid to the family of a non-Muslim is (by law) less than if the victim was a Muslim. Conversion to Islam is encouraged by entitling converts to inherit the entire share of their parents (or even uncle's) estate if their siblings (or cousins) remain non-Muslim.[55] The Bahá'í Faith, which is considered apostate, is treated much more and its members actively harassed. Iran's non-Muslim population has fallen dramatically. For example, the Jewish population in Iran dropped from 80,000 to 30,000 in the first two decades of the revolution.[56]

Many Shia Iranians have also left the country. While the revolution has made Iran more strict Islamically, an estimated three million Iranians moved abroad in the two decades following, denying Iran badly needed capital and job skills.[57][58]

Absolute poverty rose by nearly 45 percent during the first six years of the Islamic revolution (according to the government's own Planning and Budget Organization).[59] Not surprisingly the poor have risen up in riots, protesting the demolition of their shantytowns and rising food prices. Disabled war veterans have demonstrated against mismanagement of the Foundation of the Disinherited.

Death and Funeral

After eleven days in a hospital for an operation to stop internal bleeding, Khomeini died of cancer on Saturday, June 3, 1989, at the age of 89. Many Iranians poured out into the cities and streets to mourn Khomeini's death in a "completely spontaneous and unorchestrated outpouring of grief."[60] Iranian officials aborted Khomeini’s first funeral, after a large crowd stormed the funeral procession, nearly destroying Khomeini's wooden coffin in order to get a last glimpse of his body. At one point, Khomeini's body almost fell to the ground, as the crowd attempted to grab pieces of the death shroud. The second funeral was held under much tighter security. Khomeini's casket was made of steel, and heavily armed security personnel surrounded it. In accordance with Islamic tradition, the casket was only to carry the body to the burial site.

Although Iran’s economy was greatly weakened at the time of his death, the Islamic state was well established.

Successorship

Grand Ayatollah Hossein Montazeri, a major figure of the Revolution, was designated by Khomeini to be his successor as Supreme Leader. The principle of velayat-e faqih and the Islamic constitution called for the Supreme Ruler to be a marja or grand ayatollah, and of the dozen or so grand ayatollahs living in 1981 only Montazeri accepted the concept of rule by Islamic jurist. In 1989 Montazeri began to call for liberalization, freedom for political parties. Following the execution of thousands of political prisoners by the Islamic government, Montazeri told Khomeini `your prisons are far worse than those of the Shah and his SAVAK.`[61] After a letter of his complaints was leaked to Europe and broadcast on the BBC a furious Khomeini ousted him from his position as official successor. Some have said that the amendment made to Iran's constitution removing the requirement that the Supreme Leader to be a Marja, was to deal with the problem of a lack of any remaining Grand Ayatollahs willing to accept "velayat-e faqih"[62][63][64]. However, others say the reason marjas were not elected was because of their lack of votes in the Assembly of Experts, for example Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Reza Golpaygani had the backing of only 13 members of the Assembly. Furthermore, there were other marjas present who accepted "velayat-e faqih" Grand Ayatollah Hossein Montazeri continued his criticism of the regime, and in 1997 was put under house arrest for questioning the unaccountable rule exercised by the supreme leader.[65][66][67]

Political thought and legacy

Throughout his many writings and speeches, Khomeini's views on governance evolved. Originally declaring rule by monarchs or others permissible so long as sharia law was followed [68] Khomeini later adamantly opposed monarchy, arguing that only rule by a leading Islamic jurist (a marja`), would insure Sharia was properly followed (wilayat al-faqih), [69] before finally insisting the leading jurist need not be a leading one and Sharia rule could be overruled by that jurist if necessary to serve the interests of Islam and the "divine government" of the Islamic state.[70]

Khomeini was strongly against close relations with Eastern and Western Bloc nations, and he believed that Iran should strive towards self-reliance. He viewed certain elements of Western culture as being inherently decadent and a corrupting influence upon the youth. As such, he often advocated the banning of popular Western fashions, music, cinema, and literature. His ultimate vision was for Islamic nations to converge together into a single unified power, in order to avoid alignment with either side (the West or the East), and he believed that this would happen at some point in the near future.

Before taking power Khomeini expressed support for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; in Sahifeh Nour (Vol. 2

- 242), he states: "We would like to act according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We would like to be free. We would like independence." However once in power Khomeini took a firm line against dissent, warning opponents of theocracy for example: "I repeat for the last time: abstain from holding meetings, from blathering, from publishing protests. Otherwise I will break your teeth."[71] Iran adopted an alternative human rights declaration, the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, in 1990 (one year after Khomeini's death), which diverges in key respects from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Khomeini's concept of Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists (ولایت فقیه, velayat-e faqih) did not win the support of the leading Iranian Shi'i clergy of the time. While such clerics generally adhered to widely-accepted conservative theological schools of thought, Khomeini believed that interpretations should change and evolve, even if such changes were to differ radically from tradition, and that a cleric should be moved by divinely inspired guidance. Towards the 1979 Revolution, many clerics gradually became disillusioned with the rule of the Shah, although none came around to supporting Khomeini's vision of a theocratic Islamic Republic.

Many of Khomeini's political and religious ideas were considered to be progressive and reformist by leftist intellectuals and activists prior to the Revolution. However, they did not support many of his other views which conflicted with their own, in particular those that dealt with issues of secularism, women's rights, freedom of religion, and the concept of wilayat al-faqih.

Most of the democratic and social reforms that he had promised did not come to pass during his lifetime, and when faced with such criticism, Khomeini often stated that the Islamic Revolution would not be complete until Iran becomes a truly Islamic nation in every aspect, and that democracy and freedom would then come about "as a natural result of such a transformation." Khomeini's definition of democracy existed within an Islamic framework, his reasoning being that since Islam is the religion of the majority, anything that contradicted Islam would consequently be against democratic rule. His last will and testament largely focuses on this line of thought, encouraging both the general Iranian populace, the lower economic classes in particular, and the clergy to maintain their commitment to fulfilling Islamic revolutionary ideals.

These policies have been viewed by some as having alienated the lower economic classes, allowing wealthy mullahs to dominate the government.

Although Khomeini claimed that he is an advocate of democracy, many secular and religious thinkers believe that his ideas are not compatible with the idea of a democratic republic. Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi (a senior cleric and main theorist of Iranian ultraconservatives), Akbar Ganji (a pro-democracy activist and writer who is against Islamic Republic) and Abdolkarim Soroush are supporters of this viewpoint.

In Iranian Piety

Unusually, Khomeini used the title "Imam," which in Shi'a Islam is usually reserved for the infallible rule. Some people have speculated that Khomeini might have thought himself to be the Madhi, the one who would restore God's rule on earth, or that his revolution would pave the way for the Mahdi's return. Richard (1995) compared his 15-year exile in France with the occultation of al-Mahdi[72]. Iranians have claimed to see Khomeini's face in the night moon.[73]They often performed ablution before meeting him.[74]. For many Iranian, he was far from the bogey-man depicted in the Western world but rather a charismatic figure of profound faith and deep spirituality. Bennett speculates that "it is difficult for" non-Muslims outside Iran to "appreciate the love and respect he commanced; a deeply mystical personality, there is no doubt that his followers regarded him as Muhammad's heir in directing the affairs of Iran. He combined within himself routinized (legal) and charismatic (Sufi) leadership and thus, in his own person at least, resolved the struggle between these two, which has often troubled Iranian Islam"[75]

Family and descendants

In 1929, Khomeini married Batol Saqafi Khomeini, the daughter of a cleric in Tehran. They had seven children, though only five survived infancy. His daughters all married into either merchant or clerical families, and both his sons entered into religious life. The elder son, Mostafa, is rumored to have been murdered in 1977 while in exile with his father in Najaf, Iraq and Khomeini accused SAVAK of orchestrating it. Sayyed Ahmad Khomeini, (1945 - March, 1995) Khomeini's younger son, died in Teheran at age 49, under mysterious circumstances.

Khomeini's notable grandchildren include:

- Zahra Eshraghi, granddaughter, married to Mohammad Reza Khatami, head of the Islamic Iran Participation Front, the main reformist party in the country, and is considered a pro-reform character herself.

- Hassan Khomeini, Khomeini's elder grandson Seyyed Hassan Khomeini, son of the Seyyed Ahmad Khomeini, is a cleric and the trustee of Khomeini's shrine.

- Hussein Khomeini (b. 1961), (Seyyed Hossein Khomeini) Khomeini's other grandson, son of Seyyed Mustafa Khomeini, is a mid-level cleric who is strongly against the system of the Islamic Republic. In 2003 he was quoted as saying:

Iranians need freedom now, and if they can only achieve it with American interference I think they would welcome it. As an Iranian, I would welcome it.[76]

In that same year Hussein Khomeini visited the United States, where he met figures such as Reza Pahlavi II, the son of the last Shah. In that meeting they both favored a secular and democratic Iran.

Later that year, Hussein returned to Iran after receiving an urgent message from his grandmother.

In 2006, he called for an American invasion and overthrow of the Islamic Republic, telling Al-Arabiya television station viewers, "If you were a prisoner, what would you do? I want someone to break the prison [doors open].[77].

Hussein is currently under house arrest in the holy city of Qom.

Works

- Wilayat al-Faqih

- Forty Hadith (Forty Traditions)

- Adab as Salat (The Disciplines of Prayers)

- Jihade Akbar (The Greater Struggle)

Notes

- ↑ "Ruhollah Khomeini," Britannica, Ruhollah Khomeini

- ↑ Baqer Moin. Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. (London: Thomas Dunne Books, 2000. ISBN 9780312264901), 104

- ↑ Moin, 112

- ↑ "Speech No 16," IRIB World Service, Khomeini's speech against capitalism retrievd 23 May 2007

- ↑ Edward Shirley. Know Thine Enemy: A Spy's Journey Into Revolutionary Iran. (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997. ISBN 0813335884), 207.

- ↑ See "Ruhollah Musava Khomeini," Encyclopedia of World Biography Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini, Ayatollah retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Ruhollah Khomeini, and Hamid Algar, (translator and ed.) Islam and Revolution: Writing and Declarations of Imam Khomeini. (Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press, 1981. ISBN 9780933782044), 29-30

- ↑ Khomeini and Algar, 59

- ↑ Khomeini and Algar, 31, 56

- ↑ Khomeini and Algar, 54.

- ↑ Khomeini on a cassette tape, source: Gozideh Payam-ha Imam Khomeini (Selections of Imam Khomeini’s Messages), (Tehran, 1979); Amir Taheri. The Spirit of Allah: Khomeini and the Islamic Revolution. (Bethesda, MD: Adler & Adler, 1985. ISBN 9780917561047), 193

- ↑ Parviz Sabeti, head of SAVAK's "anti-subversion unit", believed the number of cassettes "exceeded 100,000." (Taheri, 1985, 193)

- ↑ Moin, 203

- ↑ Robin Wright. In the Name of God: The Khomeini Decade. (NY: Simon & Schuster, 1989. ISBN 9780671672355), 37

- ↑ Taheri, 1985, 241

- ↑ Moin, 204

- ↑ Moin, 205-206

- ↑ Moin, 206

- ↑ Ruhollah Khomeini," Britannica, Ruhollah Khomeini.

- ↑ Moin, 219

- ↑ Shaul Bakhash. The Reign of the Ayatollahs: Iran and the Islamic Revolution. (NY: Basic Books, 1984. ISBN 9780465068876), 68-69

- ↑ Asghar Schirazi. The Constitution of Iran. (London; NY: I.B. Tauris, 1997. ISBN 9781860640), 22-23

- ↑ Moin, 228

- ↑ (Resalat, 25.3.1988) (quoted in Schirazi, 1997, 69

- ↑ Moin, 228

- ↑ April 8, 1980 Broadcast call by Khomeini for the pious of Iraq to overthrow Saddam Hussein and his regime. Al-Dawa al-Islamiya party in Iraqi is the hoped for catalyst to start rebellion. From: Sandra Mackey. The Iranians: Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation. (NY: Dutton, 1996. ISBN 0525940057), 317

- ↑ Wright, 1989, 126

- ↑ William E. Smith, Will Khomeini invade Iraq in order to topple Saddam Hussein? TIME Magazine, June 4, 1982, retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Robert E. Sonnenberg, The Iran-Iraq War: Strategy or Stalemate? Global Security April 1, 1985, retrieved 15 May 2007

- ↑ Daniel Pipes, International Security (Fall 1984), Breaking All the Rules: The Middle East in U.S. Policy, danielpipes.org. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ↑ Moin, 252

- ↑ Moin, 285

- ↑ A fatwa is a legal opinion. Some argue that the fatwa was in format more like a judgement and argue that Khomeini did not have the authority to issue this under Sharia, which requires a trial

- ↑ Bernard Lewis's comment on Rushdie fatwa in Bernard Lewis. The Crisis of Islam. (NY: Random House, 2004. ISBN 978-0812967852), 141-142

- ↑ Moin, 284

- ↑ Daniel Pipes. Militant Islam Comes to America. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2002. ISBN 0393052044), 172

- ↑ "The revolutionary years," Iran Bulletin, Iran Bulletin.

- ↑ "Abbas and the 12th Imam of Shia," Ansar.org Abbas and the 12th Imam of Shia retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Holy Crime, When knife might cut the holder's hand retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ BBC News, 30 June 2005, BBC NEWS Why did Iran elect Ahmadinejad? retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Khomeini, February 1979, Iran.com "Khomeini: We want to improve your economic and spiritual lives" retrieved 25 Jan. 2007

- ↑ Based on translation of audio of Khomeini speech, Khomeini, February 1979, We want to improve your spiritual lives Iran.com. retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Niruyeh Moghavemat Basij Mobilisation Resistance Force Global Security.org. retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Secretariat of the Supreme Court of Cultural Revolution, Brief History of the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution iranculture.org. retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ "Democracy? I meant Theology," The Iranian, August 5, 2003, Democracy? I meant Theology retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Bakhash, 61

- ↑ Bakhash, 111

- ↑ Elizabeth Rubin, Alliance of Iranian Students, April 6, 2003, The Millimeter Revolution daneshjooyan.org. retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ↑ Christina Lamb, Khomeini fatwa 'led to killing of 30,000 in Iran' The Telegraph, February 4, 2001. retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Bakhash, 146

- ↑ Robin Wright. The Great Last Revolution: turmoil and transformation in Iran. (NY: Knopf, 2000. ISBN 9780375406393), 207

- ↑ Michael Theodoulou, February 3, 1998, Jews in Iran Describe a Life of Freedom Despite Anti-Israel Actions by Tehran The Christian Science Monitor,

- ↑ "The People" The People Iranonline.com.

- ↑ Wright, 2000, 210

- ↑ Wright, 2000, 216

- ↑ Wright, 2000, 207

- ↑ Mackey, 1996 368

- ↑ Frances Harrison, Huge Cost of Iranian Brain Drain BBC News, January 8, 2007 retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Janangir Amuzegar, `The Iranian Economy before and after the Revolution,` Middle East Journal 46 (3) (summer 1992): 421

- ↑ Moin, 312

- ↑ Ahmad Khomeini’s letter, in Resalat, cited in Bakhash, 282

- ↑ Moin, 293.

- ↑ Mackey, 1996, 353

- ↑ Olivier Roy. The Failure of Political Islam, translated by Carol Volk, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0674291409), 173-174

- ↑ Profile: Iran's dissident ayatollah BBC News, 30 January 2003, retrieved 25 May 2007

- ↑ Translation of Ayatollah Khomeini Letter Dismissing Montazeri IRVL.net.

- ↑ Liz Harper for the Online NewsHour, "Governing Iran", Feb. 20, 2004, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei PBS.org. retrieved 25 May 2004

- ↑ 1942 book/pamphet Kashf al-Asrar quoted in Islam and Revolution.

- ↑ 1970 book Hukumat Islamiyyah or Islamic Government, quoted in Islam and Revolution

- ↑ Hamid Algar. `Development of the Concept of velayat-i faqih since the Islamic Revolution in Iran,` paper presented at London Conference on wilayat al-faqih, in June, 1988, 135-138; Also Ressalat, (Tehran), January 7, 1988

- ↑ in Qom, Iran, October 22, 1979, quoted in Fereydoun Hoveyda. The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution. (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003. ISBN 978-0275978587), 88

- ↑ Yann Richard, and Antonia Nevill, (Translator). Shi'ite Islam. (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995. ISBN 978-1557864703), 106

- ↑ Richard, 197

- ↑ Richard, 108

- ↑ Clinton Bennett. In Search of Muhammad. (London: Cassell, 1999. ISBN 978-0304337002), 169; Richard, 58-60

- ↑ Jamie Wilson, "Make Iran Next, Says Ayatollah's Grandson," August 10, 2003, The Observer(UK)

- ↑ Philip Sherwell, The Telegraph(UK), 19-06-2006,Ayotollah's Grandson calls for US overthrow of Iran retrieved 25 May 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Algar, Hamid. Islam and Revolution 1: Writings and Declaration of Imam Khomeini. Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press, 1981. ISBN 0933782039.

- Amuzegar, Janangir, "The Iranian Economy before and after the Revolution," Middle East Journal 46 (3) (summer 1992)

- Bakhash, Shaul. The Reign of the Ayatollahs: Iran and the Islamic Revolution. NY: Basic Books, 1984. ISBN 9780465068876.

- Bennett, Clinton. In Search of Muhammad. London: Cassell, 1999. ISBN 978-0304337002.

- Dabashi, Hamid. Theology of Discontent: The Ideological Foundatation of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2005. ISBN 1412805163.

- Harney, Desmond. The priest and the king: an eyewitness account of the Iranian revolution. London: I.B. Tauris, 1998. ISBN 9781860643194.

- Hoveyda, Fereydoun. The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution. Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood, 2003. ISBN 0275978583.

- Khomeini, Ruhollah, Hamid Algar, translator and ed. Islam and Revolution: Writing and Declarations of Imam Khomeini. Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press, 1981. ISBN 9780933782044.

- Khomeini, Ruhollah, Hamid Algar, translator and ed. Sayings of the Ayatollah Khomeini: political, philosophical, social, and religious. NY: Bantam, 1980. ISBN 9780553140323.

- Lee, James. The Final Word!: An American Refutes the Sayings of Ayatollah Khomeini. NY: Philosophical Library, 1994. ISBN 0802224652.

- Lewis, Bernard. The Crisis of Islam. NY: Random House, 2004. ISBN 978-0812967852.

- Mackey, Sandra. The Iranians: Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation. NY: Dutton, 1996. ISBN 0525940057.

- Moin, Baqer. Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. London: Thomas Dunne Books, 2000. ISBN 9780312264901.

- Pipes, Daniel. Militant Islam Comes to America. NY: W. W Norton, 2002. ISBN 0393052044.

- Richard, Yann, and Antonia Nevill, Translator. Shi'ite Islam. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995. ISBN 978-1557864703.

- Roy, Olivier. The Failure of Political Islam, translated by Carol Volk, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0674291409.

- Schirazi, Asghar. The Constitution of Iran. London; NY: I.B. Tauris, 1997. ISBN 9781860640469.

- Shirley, Edward. Know Thine Enemy: A Spy's Journey Into Revolutionary Iran. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1998. ISBN 0813335884.

- Taheri, Amir. The Spirit of Allah: Khomeini and the Islamic Revolution. Bethesda, MD: Adler & Adler, 1985. ISBN 9780917561047.

- Willett, Edward C. Ayatollah Khomeini. NY: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2004. ISBN 9780823944651.

- Wright, Robin. The Great Last Revolution: turmoil and transformation in Iran. NY: Knopf, 2000. ISBN 9780375406393.

- Wright, Robin. In the Name of God: The Khomeini Decade. NY: Simon & Schuster, 1989. ISBN 9780671672355.

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- The Position of Women from the Viewpoint of Imam Khomeini

- What Happens When Islamists Take Power? The Case of Iran

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.