Difference between revisions of "Olmec" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Robot: Remove claimed tag) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

Revision as of 13:30, 2 April 2008

The Olmec were an ancient Pre-Columbian people living in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, roughly in what are the modern-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Their immediate cultural influence, however, extends far beyond this region. The Olmec flourished during the Formative (or Preclassic) period, dating from 1200 B.C.E. to about 400 B.C.E., and are believed to have been the progenitor civilization of later Mesoamerican civilizations.[1]

Overview

The Olmec heartland is characterized by swampy lowlands punctuated by low hills, ridges, and volcanoes. The Tuxtlas Mountains rise sharply in the north, along the Gulf of Mexico's Bay of Campeche. Here the Olmecs constructed permanent city-temple complexes at several locations, among them San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, La Venta, Tres Zapotes, and Laguna de los Cerros. In this heartland, the first Mesoamerican civilization would emerge and reign from 1200–400 B.C.E.

History

Early history

Olmec history originated at its base within San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, where distinctively Olmec features begin to emerge before 1200 B.C.E. The rise of civilization here was probably assisted by the local ecology of well-watered rich alluvial soil, encouraging high maize production. This ecology may be compared to that of other ancient centers of civilization: the Nile, Indus, and Yellow River valleys, and Mesopotamia. It is thought that the dense population concentration at San Lorenzo encouraged the rise of an elite class that eventually ensured Olmec dominance and provided the social basis for the production of the symbolic and sophisticated luxury artifacts that define Olmec culture. Many of these luxury artifacts, such as jade, obsidian and magnetite, came from distant locations and suggest that early Olmec elites had access to an extensive trading network in Mesoamerica. The source of the most valued jade, for example, is found in the Motagua River valley in eastern Guatemala, and their obsidian is mainly from sources also in the Guatemala highlands, such as El Chayal and San Martín Jilotepeque.

La Venta

© George & Audrey DeLange, used with permission.

The first Olmec center, San Lorenzo, was all but abandoned around 900 B.C.E. at about the same time that La Venta rose to prominence. Environmental changes may have been responsible for this move, with certain important rivers changing course. A wholesale destruction of many San Lorenzo monuments also occurred around this time, circa 950 B.C.E., which may point to an internal uprising or, less likely, an invasion.[2] Following the decline of San Lorenzo, La Venta became the most prominent Olmec center, lasting from 900 B.C.E. until its abandonment around 400 B.C.E. During this period, the Great Pyramid and various other ceremonial complexes were built at La Venta.[3]

Decline

It is not known with any clarity what caused the eventual extinction of the Olmec culture. It is known that between 400 and 350 B.C.E., population in the eastern half of the Olmec heartland dropped precipitously, and the area would remain sparsely inhabited until the 19th century.[4] This depopulation was likely the result of environmental changes: perhaps the result of important rivers changing course or silting up due to agricultural practices.[5]

What ever the cause, within a few hundred years of the abandonment of the last Olmec cities, successor cultures had become firmly established. The Tres Zapotes site, on the western edge of the Olmec heartland, continued to be occupied well past 400 B.C.E., but without the hallmarks of the Olmec culture. This post-Olmec culture, often labeled Epi-Olmec, has features similar to those found at Izapa, some distance to the southeast.

Notable innovations

As the first civilization in Mesoamerica, the Olmecs are credited, or speculatively credited, with many "firsts," including the Mesoamerican ballgame, bloodletting and perhaps human sacrifice, writing and epigraphy, and the invention of zero and the Mesoamerican calendar. Their political arrangements of strongly hierarchical city-state kingdoms were repeated by nearly every other Mexican and Central American civilization that followed. Some researchers, including artist and art historian Miguel Covarrubias, even postulate that the Olmecs formulated the forerunners of many of the later Mesoamerican deities.[6]

- See also Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures for a discussion of the archaeological debate on this issue.

Mesoamerican ballgame

The Olmec, whose name means "rubber people" in the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs (see below), were likely the originators of the Mesoamerican ballgame so prevalent among later cultures of the region and used for recreational and religious purposes.[7] A dozen rubber balls dating to 1600 B.C.E. or earlier have been found in El Manatí, an Olmec sacrificial bog 10 kilometres east of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan.[8] These balls predate the earliest ballcourt yet discovered at Paso de la Amada, circa 1400 B.C.E. The fact that the balls were found with other sacrificial items, including pottery and jadeite celts indicates that even at this early date, the ballgame had religious and ritual connotations.

Bloodletting and sacrifice

There is a strong case that the Olmecs practiced bloodletting, or autosacrifice. Numerous natural and ceramic stingray spikes and maguey thorns have been found in the archaeological record of the Olmec heartland.[9]

The argument that the Olmecs instituted human sacrifice is significantly more speculative. No Olmec or Olmec-influenced sacrificial artifacts have yet been discovered and there is no Olmec or Olmec-influenced artwork that unambiguously shows sacrificial victims (similar, for example, to the danzante figures of Monte Albán) or scenes of human sacrifice (such as can be seen in the famous ballcourt mural from El Tajin).

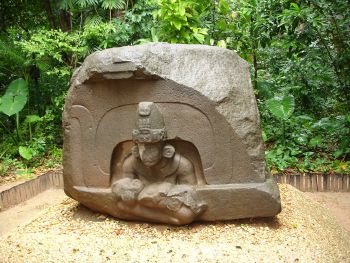

However, at the El Manatí site, disarticulated skulls and femurs as well as complete skeletons of newborn or unborn children have been discovered amidst the other offerings, leading to speculation concerning infant sacrifice. It is not yet known, though, how the infants met their deaths.[10] Some authors have also associated infant sacrifice with Olmec ritual art showing limp "were-jaguar" babies, most famously in La Venta's Altar 5 (to the right) or Las Limas figure (see Religion below). Definitive answers will need to await further findings.

Writing

The Olmec may have been the first civilization in the Western Hemisphere to develop a writing system. Symbols found in 2002 and 2006 date to 650 B.C.E.[11] and 900 B.C.E.[12] respectively, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing dated to about 500 B.C.E.

The 2002 find at the San Andrés site shows a bird, speech scrolls, and glyphs that are similar to the later Mayan hieroglyphs.[13]

Known as the Cascajal block, the 2006 find from a site near San Lorenzo, shows a set of 62 symbols, 28 of which are unique, carved on a serpentine block. A large number of prominent archaeologiests have hailed this find as the "earliest pre-Columbian writing".[14] Others are skeptical because of the stone's singularity, the fact that it had been removed from any archaeological context, and because it bears no apparent resemblance to any other Mesoamerican writing system.

There are also well-documented later hieroglyphs known as "Epi-Olmec," and while there are some who believe that Epi-Olmec may represent a transitional script between an earlier Olmec writing system and Maya writing, the matter remains unsettled.

This is the second oldest Long Count date yet discovered. The numerals 7.16.6.16.18 translate to September 3, 32 B.C.E. (Julian). The glyphs surrounding the date are what is thought to be one of the few surviving examples of Epi-Olmec script.

Compass

The find of an Olmec hematite artifact, fitted with a sighting mark and found in experiment as fully operational as a compass, has led the American astronomer John Carlson after radiocarbon dating to propose that "the Olmec may have discovered and used the geomagnetic lodestone compass earlier than 1000 B.C.E.".[15] Carlson suggests that the Olmecs may have used such devices for directional orientation of the dwellings of the living and the interments of the dead.

Mesoamerican Long Count calendar & invention of the zero concept

The Long Count calendar used by many subsequent Mesoamerican civilizations, as well as the concept of zero, may have been devised by the Olmecs. Because the six artifacts with the earliest Long Count calendar dates were all discovered outside the immediate Maya homeland, it is likely that this calendar predated the Maya and was possibly the invention of the Olmecs.[16] Indeed, three of these six artifacts were found within the Olmec heartland area. However, the fact that the Olmec civilization had come to an end by the 4th century B.C.E., several centuries before the earliest known Long Count date artifact, argue against an Olmec origin.

The Long Count calendar required the use of zero as a place-holder within its vigesimal (base-20) positional numeral system. A shell glyph—![]() —was used as a zero symbol for these Long Count dates, the second oldest of which, on Stela C at Tres Zapotes, has a date of 32 B.C.E. This is one of the earliest uses of the zero concept in history.[17]

—was used as a zero symbol for these Long Count dates, the second oldest of which, on Stela C at Tres Zapotes, has a date of 32 B.C.E. This is one of the earliest uses of the zero concept in history.[17]

- See also History of zero

Olmec art

Olmec artforms remain in works of both monumental statuary and small jadework. Much Olmec art is highly stylized and uses an iconography reflective of a religious meaning. Some Olmec art, however, is surprisingly naturalistic, displaying an accuracy of depiction of human anatomy perhaps equaled in the pre-Columbian New World only by the best Maya Classic era art. Common motifs include downturned mouths and slit-like slanting eyes, both of which are seen as representations of "were-jaguars." Olmec figurines are also found abundantly in sites throughout the Formative Period.

In addition to human subjects, Olmec artisans were adept at animal portrayals, for example, the fish vessel to the right or the bird vessel in the gallery below.

Olmec colossal heads

Perhaps the best-recognized Olmec art are the enormous helmeted heads. As no known pre-Columbian text explains these, these impressive monuments have been the subject of much speculation. Given the individuality of each, these heads seem to be portraits of famous ball players or perhaps kings rigged out in the accoutrements of the game.[18]

According to Grove,[19] the unique elements in the headgear can also be recognized in headdresses of human figures on other Gulf Coast monuments, suggesting that these are personal or group symbols.

The heads range in size from the Rancho La Cobata head, at 3.4 m high, to the pair at Tres Zapotes, at 1.47 m. Some sources estimate that the largest weighs as much as 40 tons, although most reports place the larger heads at 20 tons.

The heads were carved from single blocks or boulders of volcanic basalt, quarried in the Tuxtlas Mountains. The Tres Zapotes heads were sculpted from basalt found on San Martin Volcano. The lowland heads were possibly carved from the Cerro Cintepec. It is possible that the heads were carried on large balsa rafts from the Llano del Jicaro quarry to their final locations. To reach La Venta, roughly 80 km (50 miles) away, the rafts would have had to move out onto choppy waters of the Bay of Campeche.

Some of the heads, and many other monuments, have been variously mutilated, buried and disinterred, reset in new locations and/or reburied. It is known that some monuments had been recycled or recarved, but it is not known whether this was simply due to the scarcity of stone or whether these actions had ritual or other connotations. It is also suspected that some mutilation had significance beyond mere destruction, but some scholars still do not rule out internal conflicts or, less likely, invasion as a factor.[20]

There have been 17 colossal heads unearthed to date.

| Site | Count | Designations |

|---|---|---|

| San Lorenzo | 10 | Colossal Heads 1 through 10 |

| La Venta | 4 | Monuments 1 through 4 |

| Tres Zapotes | 2 | Monuments A & Q |

| Rancho la Cobata[21] | 1 | Monument 1 |

Beyond the heartland

Olmec-style artifacts, designs, figurines, monuments and iconography have been found in the archaeological records of sites hundreds of kilometres outside the Olmec heartland. These sites include:

- Tlatilco and Tlapacoya, major centers of the Tlatilco culture in the Valley of Mexico, where artifacts include hollow baby-face motif figurines and Olmec designs on ceramics.

- Chalcatzingo, in Valley of Morelos, which features Olmec-style monumental art and rock art with Olmec-style figures.

- Teopantecuanitlan, in Guerrero, which features Olmec-style monumental art as well as city plans with distinctive Olmec features.

Other sites showing probable Olmec influence include Abaj Takalik in Guatemala and Zazacatla in Morelos. The Juxtlahuaca and Oxtotitlan cave paintings are attributed by most researchers to the Olmecs.[22]

Many theories have been advanced to account for the occurrence of Olmec influence far outside the heartland, including long-range trade by Olmec merchants, Olmec colonization of other regions, Olmec artisans travelling to other cities, conscious imitation of Olmec artistical styles by developing towns – some even suggest the prospect of Olmec military domination outside of their heartland or that the Olmec iconography was actually developed outside the heartland.[23]

The generally accepted, but by no means unanimous, interpretation is that the Olmec-style artifacts, in all sizes, became associated with elite status and were adopted by non-Olmec Formative Period chieftains in an effort to bolster their status.[24]

Daily life

Ethnicity and language

While the actual ethnicity of the Olmec remains unknown, various hypotheses have been put forward. In 1976 Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman published a paper which argued that there are a core number of loanwords which have apparently spread from a Mixe-Zoquean language into many other Mesoamerican languages.[25] Campbell and Kaufman go on to argue that these core loanwords can be seen as an indicator that the Olmecs, the first "highly civilized society" of Mesoamerica, spoke a language which is an ancestor of the Mixe-Zoquean languages, and that they spread a vocabulary particular to their culture to the other peoples of Mesoamerica.

Since the Mixe-Zoquean languages still are, and historically are known to have been, spoken in an area corresponding roughly to the Olmec heartland, and since the Olmec culture is now generally regarded as the first "high culture" of Mesoamerica, it has generally been regarded as probable that the Olmec spoke a Mixe-Zoquean language.[26]

Religion and mythology

Olmec religious activities were performed by a combination of rulers, full-time priests, and shamans. The rulers were probably the most important religious figures, with their links to the Olmec deities or supernaturals providing legitimacy for their rule.[27] There is also considerable evidence for shamans in the Olmec archaeological record, particularly in the so-called "transformation figurines."

Olmec mythology has left no documents comparable to the Popul Vuh from Maya mythology, and therefore any exposition of Olmec mythology must rely on interpretations of surviving monumental and portable art (such as the Las Limas figure at top right), and comparisons with other Mesoamerican mythologies. Olmec art shows that such deities as the Feathered Serpent and the Rain Spirit were already in the Mesoamerican pantheon in Olmec times.

Social and political organization

Little is directly known about the societal or political structure of Olmec society. Although it is assumed by most researchers that the colossal heads and several other sculptures represent rulers, we have nothing like the Maya stelae (see drawing) which name specific rulers and provide the dates of their rule.

Instead, archaeologists have relied on the data that they do have, such as large- and small-scale site surveys.[28] The Olmec heartland, for example, shows considerable centralization, first at San Lorenzo and then at La Venta. No other Olmec heartland site comes close to these in terms of size or in quantity and quality of architecture and sculpture. Diehl, for example, refers to San Lorenzo and La Venta as "Regal-Ritual Cities".[29]

This demographic centralization leads archaeologists to propose that Olmec society was also highly centralized, with a strongly hierarchial structure, concentrated first at San Lorenzo and then at La Venta, with an elite that was able to use their control over materials such as monumental stone and water to exert control and legitimize their regime.[30]

Village life and diet

Despite their size, San Lorenzo and La Venta were largely ceremonial centers, and the vast majority of the Olmec lived in villages similar to present-day villages and hamlets in Tabasco and Veracruz.

These villages were located on higher ground and consisted of several scattered houses. A modest temple may have been associated with the larger villages. The individual dwellings would consist of a house, an associated lean-to, and one or more storage pits (similar in function to a root cellar). A nearby garden was used for medicinal and cooking herbs and for smaller crops such as the domesticated sunflower. Fruit trees, such as avocado or cacao, were likely available nearby.[31]

Although the river banks were used to plant crops between flooding periods, the Olmecs also likely practiced swidden (or slash-and-burn) agriculture to clear the forests and shrubs, and to provide new fields once the old fields were exhausted.[32] Fields were located outside the village, and were used for maize, beans, squash, manioc, sweet potato, as well as cotton. Based on studies of two villages in the Tuxtlas Mountains, maize cultivation became increasingly important to the Olmec diet over time, although the diet remained fairly diverse.[33]

The fruits and vegetables were supplemented with fish, turtle, snake, and mollusks from the nearby rivers, and crabs and shellfish in the coastal areas.

Birds were available as food sources, as were game including peccary, oppossum, raccoon, rabbit, and in particular deer.[34] Despite the wide range of hunting and fishing available, midden surveys in San Lorenzo have found that the domesticated dog was the single most plentiful source of animal protein.[35]

History of scholarly research on the Olmec

Olmec culture was unknown to historians until the mid-19th century. In 1862 the fortuitous discovery of a colossal head near Tres Zapotes, Veracruz by José Melgar y Serrano[36] marked the first significant rediscovery of Olmec artifacts. In the latter half of the 19th century, Olmec artifacts such as the Kunz Axe (right) came to light and were recognized as belonging to a unique artistic tradition.

Frans Blom and Oliver La Farge made the first detailed descriptions of La Venta and San Martin Pajanpan Monument 1 during their 1925 expedition. However, at this time, most archaeologists assumed the Olmec were contemporaneous with the Maya – even Blom and La Farge were, in their own words, "inclined to ascribe them to the Maya culture".[37].

Matthew Stirling of the Smithsonian Institution conducted the first detailed scientific excavations of Olmec sites in the 1930s and 1940s. Stirling, along with art historian Miguel Covarrubias, became convinced that the Olmec predated most other known Mesoamerican civilizations.

In counterpoint to Stirling, Covarrubias, and Alfonso Caso, Mayanists Eric Thompson and Sylvanus Morley argued for Classic era dates for the Olmec artifacts. The question of Olmec chronology came to a head at a 1942 Tuxtla Gutierrez conference, where Alfonso Caso declared that the Olmecs were the "mother culture" ("cultura madre") of Mesoamerica.[38]

Shortly after the conference, radiocarbon dating proved the antiquity of the Olmec civilization, although the "mother culture" question generates much debate even 60 years later.

Etymology of the name "Olmec"

The name "Olmec" means "rubber people" in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec, and was the Aztec name for the people who lived in the area of the Olmec heartland in the 15th and 16th centuries, some 2000 years after what we know as the Olmec culture died out. The term "rubber people" refers to the ancient practice, spanning from ancient Olmecs to Aztecs, of extracting latex from Castilla elastica, a rubber tree in the area. The juice of a local vine, Ipomoea alba, was then mixed with this latex to create rubber as early as 1600 B.C.E..[39]

Early modern explorers and archaeologists, however, mistakenly applied the name "Olmec" to the rediscovered ruins and artifacts in the heartland decades before it was understood that these were not created by people the Aztecs knew as the "Olmec," but rather a culture that was 2000 years older. Despite the mistaken identity, the name has stuck.

It is not known what name the ancient Olmec used for themselves; some later Mesoamerican accounts seem to refer to the ancient Olmec as "Tamoanchan".[40] Another term sometimes used to describe the Olmec culture is tenocelome, meaning "mouth of the jaguar."

Alternative origin speculations

In part because the Olmecs developed the first Mesoamerican civilization and in part because so little is known of the Olmecs (relative, for example, to the Maya or Aztec), a wide number of Olmec alternative origin speculations have been put forth. Although several of these speculations, particularly the theory that the Olmecs were of African origin, have become well-known within popular culture, popularized by Ivan van Sertima's book They Came Before Columbus, they are not considered credible by the vast majority of Mesoamerican researchers.

Gallery

See also

- El Azuzul - a small archaeological site in the Olmec heartland

- Cerro de las Mesas - a post-Olmec archaeological site

Footnotes

- ↑ See Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures for a more in depth treatment of the "mother/sister culture" question.

- ↑ Coe (1967), p. 72. Alternatively, the mutilation of these monuments may be unrelated to the decline and abandonment of San Lorenzo. Some researchers believe that this mutilation had ritualistic aspects, particularly since most mutilated monuments were reburied in a row.

- ↑ Diehl, p. 72-74.

- ↑ Diehl, p. 82. Nagy, p. 270, however, is more circumspect, stating that in the Grijalva river delta, on the eastern edge of the heartland, "the local population had significantly declined in apparent population density. . . A low-density Late Preclassic and Early Classic occupation . . . may have existed; however, it remains invisible." .

- ↑ Diehl, p. 82.

- ↑ Covarrubias, p. 27.

- ↑ Pool, p. 295.

- ↑ Ortiz C.

- ↑ For example, see Joyce et al., "Olmec Bloodletting: An Iconographic Study".

- ↑ Ortiz et al., p. 249.

- ↑ Script Delivery: New World writing takes disputed turn

- ↑ Writing May Be Oldest in Western Hemisphere

- ↑ Pohl et al. (2002).

- ↑ Skidmore. These prominent proponents include Michael D. Coe, Richard A. Diehl, Karl Taube, and Stephen D. Houston.

- ↑ John B. Carlson, “Lodestone Compass: Chinese or Olmec Primacy? Multidisciplinary Analysis of an Olmec Hematite Artifact from San Lorenzo, Veracruz, Mexico,” Science, New Series, Vol. 189, No. 4205 (Sep. 5, 1975), pp. 753-760 (753)

- ↑ Diehl, p. 186.

- ↑ The Monument 1 in the Maya site El Baúl, Guatemala, bears a Long Count Date of 37 B.C.E.

- ↑ Coe (2002), p. 69: "They wear headgear rather like American football helmets which probably served as protection in both war and in the ceremonial game played… throughout Mesoamerica".

- ↑ Grove, p. 55.

- ↑ Diehl, p. 119.

- ↑ Rancho La Cobata is located near Tres Zapotes.

- ↑ For example, Diehl, p. 170.

- ↑ Flannery et al. (2005) hint that Olmec iconography was first developed in the Tlatilco culture.

- ↑ See for example Reilly; Stevens (2007); Rose (2007). For a full discussion, see Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures.

- ↑ For example the words for "incense," "cacao," "corn," many names of various fruits, "nagual/shaman," "tobacco," "adobe," "ladder," "rubber," "corn granary," "squash/gourd," and "paper" in many Mesoamerican languages seem to have been borrowed from an ancient Mixe-Zoquean language.

- ↑ Campbell & Kaufman (1976), pp. 80–9.

- ↑ Diehl, p. 106. See also J. E. Clark, , p. 343, who says "much of the art of La Venta appears to have been dedicated to rulers who dressed as gods, or to the gods themselves".

- ↑ See Santley, et al., p.4, for a discussion of Mesoamerican centralization and decentralization. See Cyphers for a discussion of the meaning of monument placement.

- ↑ Diehl, p. 61-62.

- ↑ See, for example, Cyphers, for a more detailed discussion.

- ↑ This diet section is built from Diehl (2004), Davies, and Pope et al.

- ↑ Pohl.

- ↑ VanDerwarker, p. 195, and Lawler, Archaeology (2007), p. 23, quoting VanDerwarker.

- ↑ VanDerwarker, p. 141-144. VanDerwarker notes that some bone types are better preserved than others: "large mammal bones more than small mammal bones, mammal bones more than bird bones, etc," p. 117, and therefore the samplings will likely be biased toward the larger mammals, with birds and fish underpresented.

- ↑ Davies, p. 39.

- ↑ Stirling, p. 8.

- ↑ Quoted in Coe (1968), p. 40.

- ↑ "Esta gran cultura, que encontramos en niveles antiguos, es sin duda madre de otras culturas, como la maya, la teotihuacana, la zapoteca, la de El Tajín, y otras” ("This great culture, which we encounter in ancient levels, is without a doubt mother of other cultures, like the Maya, the Teotihuacana, the Zapotec, that of El Tajin, and others".) Caso (1942), p. 46.

- ↑ Rubber Processing, MIT.

- ↑ Coe (2002) refers to an old Nahuatl poem cited by Miguel Leon-Portilla which itself refers to a land called "Tamoanchan":

Coe interprets Tamoanchan as a Mayan language word meaning 'Land of Rain or Mist' (p. 61).in a certain era

which no one can reckon

which no one can remember

[where] there was a government for a long time".

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arnaiz-Villena A, Vargas-Alarcon G, Granados J, Gomez-Casado E, Longas J, Gonzales-Hevilla M, Zuniga J, Salgado N, Hernandez-Pacheco G, Guillen J, Martinez-Laso J.; HLA genes in Mexican Mazatecans, the peopling of the Americas and the uniqueness of Amerindians. - Bibliographic entry in PubMed.

- Campbell, L., and T. Kaufman (1976), "A Linguistic Look at the Olmecs," American Antiquity, 41.

- Clark, John E. (2000) "Gulf Lowlands: South Region," in Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: an Encyclopedia, ed. Evans, Susan; Routledge.

- Coe, M.D. (1967) "San Lorenzo and the Olmec Civilization," in Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec, Dumbarton Oaks, Washingon, D.C.

- Coe, M.D. (2002) Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs London: Thames and Hudson; pp. 64, 75-76.

- Covarrubias, Miguel (1946) "Olmec Art or the Art of La Venta," trans. Robert Pirazzini, reprinted in Pre-Columbian Art History: Selected Readings," ed. A. Cordy-Collins, Jean Stern, 1977, pp. 1-34.

- Cyphers, Ann (1999) "From Stone to Symbols: Olmec Art in Social Context at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán," in Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica, David C. Grove and Rosemary A. Joyce, eds., Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

- Davies, Nigel (1982) The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico, Penguin Books.

- Diehl, Richard A. (2004) The Olmecs: America's First Civilization, Thames & Hudson, London.

- Fagan, Brian (1991) Kingdoms of Gold, Kingdoms of Jade, Thames and Hudson, London.

- Flannery, Kent; Balkansky, A. K.; Feinman, Gary M.; Grove, David C.; Marcus, Joyce; Redmond, Elsa M.; Reynolds, Robert G.; Sharer, Robert J.; Spencer, Charles S.; Yaeger, Jason (2005) "Implications of new petrographic analysis for the Olmec "mother culture" model," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, accessed March 2007.

- Grove, D. C. (1981) "Olmec monuments: Mutilation as a clue to meaning," in The Olmec and their Neighbors: Essays in Memory of Matthew W. Stirling. E. P. Benson, ed.; Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, pp. 49–68.

- Guimaräes, A. P. (2004) "Mexico and the early history of magnetism," in Revista mexicana de Fisica, v 50 (1), June 2004, p 51 - 53.

- Joyce, Rosemary; Edging, Richard; Lorenz, Karl; Gillespie, Susan, (1991) "Olmec Bloodletting: An Iconographic Study" in Sixth Palenque Roundtable, 1986, ed. V. Fields, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

- Lawler, Andrew (2007) "Beyond the Family Feud," in Archaeology; Mar/Apr 2007, Vol. 60 Issue 2, pp. 20-25.

- Magni, Caterina (2003) Les Olmèques. Des origines au mythe, Seuil, Paris.

- Maldonado-Salazar, Carlos; Hector; Cesar; David; Olmec etymology source "Olmecs" (1999), ThinkQuest, accessed June 4, 2007.

- National Science Foundation; Scientists Find Earliest "New World" Writings in Mexico, 2002.

- Niederberger Betton, Christine (1987) Paléopaysages et archéologie pré-urbaine du bassin de México. Tomes I & II published by Centro Francés de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos, Mexico, D.F. (Resume)

- Ortíz C., Ponciano; Rodríguez, María del Carmen (1999) "Olmec Ritual Behavior at El Manatí: A Sacred Space" in Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica, eds. Grove, D. C.; Joyce, R. A., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C., p. 225 - 254.

- Pohl, Mary; Kevin O. Pope, Christopher von Nagy (2002) "Olmec Origins of Mesoamerican Writing, in Science, vol. 298, pp. 1984-1987.

- Pohl, Mary "Economic Foundations of Olmec Civilization in the Gulf Coast Lowlands of México," Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc., accessed March 2007.

- Pool, Christopher (2007) Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica, Cambridge University Press.

- Pope, Kevin; Pohl, Mary E. D.; Jones, John G.; Lentz, 3 David L.; von Nagy, Christopher; Vega, Francisco J.; Quitmyer Irvy R.; "Origin and Environmental Setting of Ancient Agriculture in the Lowlands of Mesoamerica," Science, 18 May 2001:Vol. 292. no. 5520, pp. 1370 - 1373.

- Reilly III, F. Kent, “Art, Ritual, and Rulership in the Olmec World” in Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: a Reader, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, p. 369-395.

- Rose, Mark (2005) "Olmec People, Olmec Art", in Archaeology (online), the Archaeological Institute of America, accessed February 2007.

- Santley, Robert S., Michael J. Berman, Rani T. Alexander (1991) "The Politicization of the Mesoamerican Ballgame and its Implications for the Interpretation of the Distribution of Ballcourts in Central Mexico," in The Mesoamerican Ballgame, =Vernon Scarborough, David R. Wilcox eds., University of Arizona Press, ISBN 0-8165-1360-0.

- Skidmore, Joel (2006) "The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing," Mesoweb, accessed March 2007.

- Stevenson, Mark (2007) “Olmec-influenced city found in Mexico”, Associated Press, accessed February 8, 2007.

- Stirling, Matthew (1967) "Early History of the Olmec Problem," in Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec, E. Benson, ed., Dumbarton Oaks, Washingon, D.C.

- Stoltman, J. B., Marcus, J., Flannery, K. V., Burton, J. H., Moyle, R. G., "Petrographic evidence shows that pottery exchange between the Olmec and their neighbors was two-way," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, August 9, 2005, v. 102, n. 32, pp. 11213-11218 .

- Taube, Karl (2004), "The Origin and Development of Olmec Research," in Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

- VanDerwarker, Amber (2006) Farming, Hunting, and Fishing in the Olmec World, University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292709803.

- von Nagy, Christopher (1997) "The Geoarchaeology of Settlement in the Grijalva Delta," in Olmec to Aztec: Settlement Patterns in the Ancient Gulf Lowlands," Barbara L. Stark and Philip J. Arnold III, Eds., University of Arizona Press, Tucson, ISBN 0-8165-1689-8.

- Wilford, John Noble; Mother Culture, or Only a Sister?, The New York Times, March 15, 2005.

External links

- Olmec Blue Jade Source

- El contexto Arquaeologico de la cabeza colosal olmeca numero 7 de San Lorenzo

- Stone Etchings Represent Earliest New World Writing Scientific American; Ma. del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez, Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos, Michael D. Coe, Richard A. Diehl, Stephen D. Houston, Karl A. Taube, Alfredo Delgado Calderón, Oldest Writing in the New World, Science, Vol 313, Sep 15 2006, pp1610-1614.

- Drawings and photographs of the 17 colossal heads

- Olmecs Origins in the Mesoamerican Southern Pacific Lowlands

| Pre-Columbian Civilizations and Cultures | ||||

| North America | Ancient Pueblo (Anasazi) – Fremont – Mississippian | |||

| Mesoamerica | Huastec – Izapa – Mixtec – Olmec – Pipil – Tarascan – Teotihuacán – Toltec – Totonac – Zapotec | |||

| South America | Norte Chico – Chavín – Chibcha – Chimor – Chachapoya – Huari – Moche – Nazca – Tairona – Tiwanaku | |||

| Main civilizations | ||||

| The Aztec Empire | The Maya civilization | The Inca Empire | ||

| Language | Nahuatl language | Mayan languages | Quechua | |

| Writing | Aztec writing | Mayan writing | ||

| Religion | Aztec religion | Maya religion | Inca religion | |

| Mythology | Aztec mythology | Maya mythology | Inca mythology | |

| Calendar | Aztec calendar | Maya calendar | ||

| Society | Aztec society | Maya society | Inca society | |

| Infrastructure | Chinampas | Maya architecture | Inca architecture Inca road system | |

| History | Aztec history | Inca history | ||

| Conquest | Spanish conquest of Mexico Hernán Cortés |

Spanish conquest of Yucatán Francisco de Montejo Spanish conquest of Guatemala Pedro de Alvarado |

Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire Francisco Pizarro | |

| People | Moctezuma I Moctezuma II Cuitláhuac Cuauhtémoc |

Pacal the Great Tecun Uman |

Manco Capac Pachacutec Atahualpa | |

| See also | ||||

| Indigenous peoples of the Americas – Population history of American indigenous peoples – Pre-Columbian art | ||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.